I assigned my students ‘Everything that Rises Must Converge’ before actually having read it myself because it was the only Flannery O’Connor story in the anthology we were using. Familiar with O’Connor – while I have not read everything she’s written I have read particular stories many times – I figured it would be good enough to get something out of, but I wished Good Country People was there in its place because even though the characters technically don’t have sex, what they do amounts to arguably the best sex scene in literature. And so with resistance and some annoyance that the story began with a man taking his mother to a ‘reducing class’ – the last thing I wanted to read about, I thought, was a bachelor and his widowed mother taking a bus trip to the Y for a ‘reducing class’; and too as I read I realized I had read the story, or at least read part of it when a teenager, intuited this was not leading up to a bizarre sex scene – I belligerently entered what I myself had assigned and near the top of the second page realized this was the best thing in 100 Years Of The Best American Short Stories.

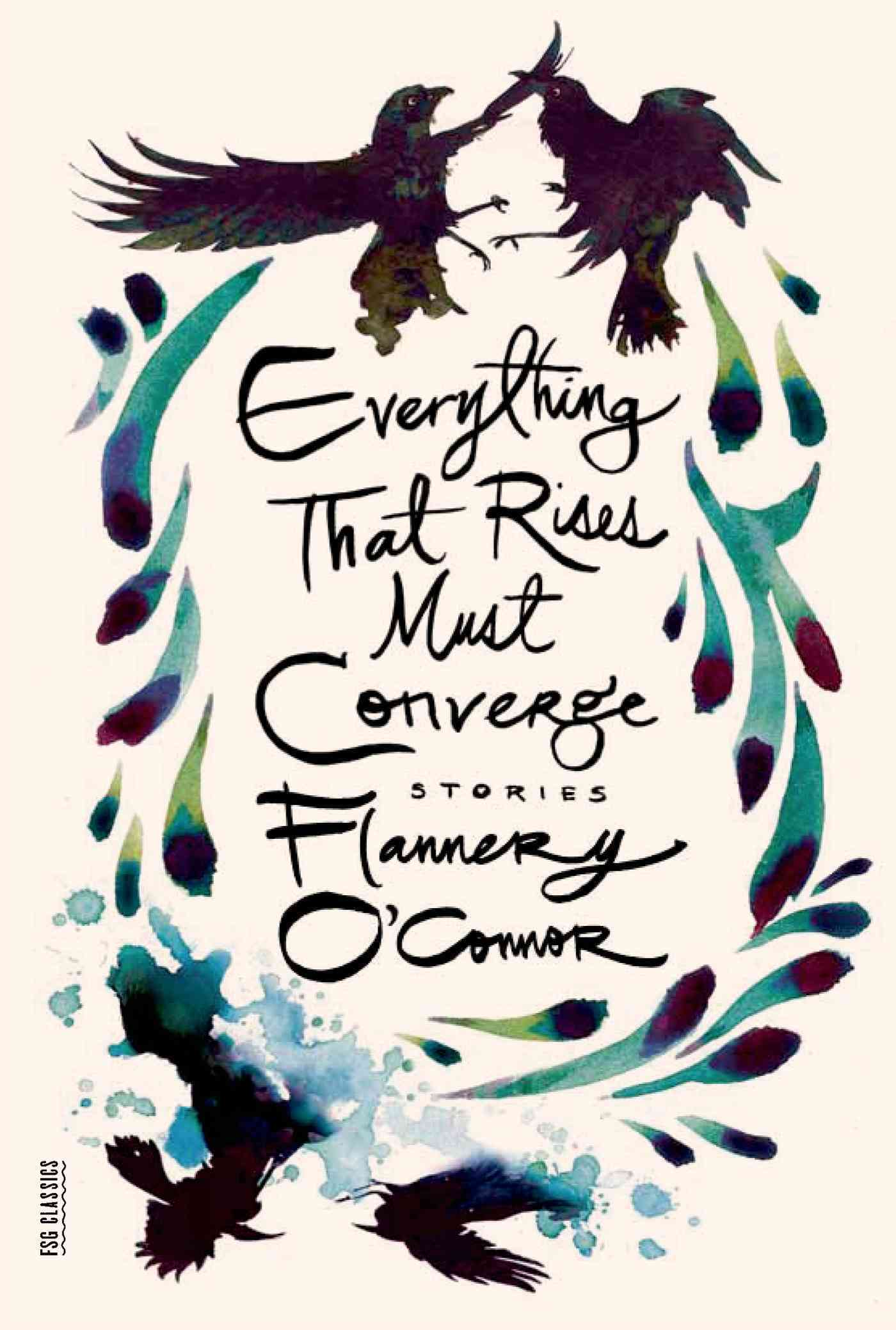

Something about the writing itself, what lives between the lines, sets it in a league that makes throwing it into competition seem as absurd as setting out to discover which human being has the ‘best’ face. That the story the title piece of O’Connor’s 1965 collection Everything that Rises Must Converge, itself explores the question of human value, that it renders false and ridiculous Julian’s idea that he is better than his mother, and his mother’s idea that she is better than the black population in America whose rise she resents, has for me the effect of nailing and then blowing up one’s most casual instances of falling into an illusion of a fixed moral, social, or personal sense of superiority over another. The story does this by being totally itself in a way that is hard to explain. In it being so completely itself, turning in on and splitting and questioning and exploding itself, it rises above comparison. It is best because it eviscerates the idea of best, and as usual O’Connor’s gift for irony is not used to simply celebrate cleverness but to cut through the lies that, while protecting the ego, stifle the spirit. In devastating the reader she clears a space for transformation.