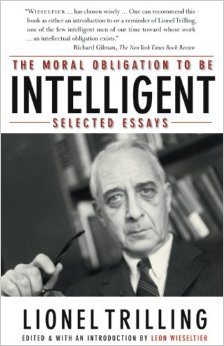

Does anyone my age (officially Gen-X, but still totally ‘with it’) read Lionel Trilling? I was aware, certainly, that he was a towering figure in mid-twentieth century letters, casting a long enough shadow to get name-checked in this prime bit of 90s indie cinema. But this far into the twenty-first century? In a decade or so of mucking around in literary circles, I truly can’t recall hearing Trilling referenced in a classroom, a Brooklyn publishing party or a beery conversation among writer friends. A surprise and an education, then, to crack open this volume and discover how essential it is.

What’s here? To my eyes, near-definitive essays on Orwell and Babel (I don’t think I properly understood Red Calvary until reading Trilling). A merciless and entirely sane excavation of the notion that neurosis/madness and literary genius are somehow intertwined. The tracking, in a particularly far-reaching essay, of the pleasure (and anti-pleasure) principle through Wordsworth, Balzac, Dostoyevsky, Yeats and, of course, Freud. A fascinatingly cagey but no less honest appraisal of teaching the Moderns and the queasiness of watching ‘the acculturation of the anti-cultural . . . the legitimization of the subversive’. A disquisition on the Leavis–Snow Controversy – a learned tiff over whether our education system ought to privilege the sciences over the humanities – that still feels spot-on relevant fifty years on.

Perhaps not surprising, then, that Trilling might be out of fashion at the moment. But, after a week of delving into these essays, I feel that’s a shame. We’re living in a prodigious era of cultural criticism – and thank God it no longer all comes from white men writing about other white men – but sometimes I find myself getting cranky about the sheer volume of opinion and analysis out there and how quickly it arrives: days, hours, even minutes after the press conference or the film release or the incendiary tweet. Trilling writes about dauntingly huge concepts: pleasure, will, power, democracy, the proletariat, the spirit. He’s a high-flying bird, living in an atmosphere perhaps too rarefied for our era. Still, it’s thrilling to watch him swoop and dive and then rise and rise, in his meticulous spirals, to ever higher altitudes.