‘His room filled with the roaring of the wind, and he heard the sound of clomping boots gradually approaching the alcove in which his bed was situated. By now he was utterly terrified. Then the door of the alcove itself flew open, and there it was, a great troll, stooping down at first as it approached, then suddenly looming up over his bed, its head grazing the ceiling, its face dark and blotchy like an old melon rind. It’s blazing eyes scanned the room, and its cavernous mouth lolled open, revealing shining fangs more than three inches long. Its tongue flickered from side to side, and from its throat there issued a terrible rasping sound that reverberated through the room.’

– from ‘The Troll’ by Pu Songling, translated by John Minford.

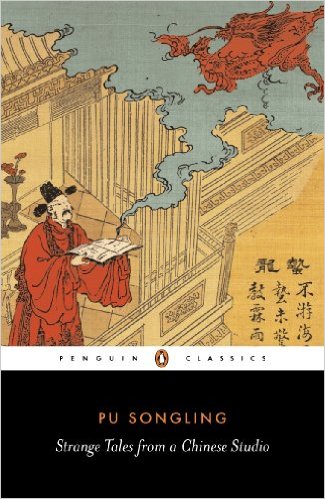

Ghosts, zombies, trolls, seductive fox-spirits and demon-slaying monks: like the Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Anderson and Giambattista Basile, Pu Songling (1640-1715) gathered scraps of fable and folklore and stitched them deep into the collective cultural imagination.

The 237 Strange Tales comprise a mishmash of different genres, ranging from carefully wrought didactic fables to brief descriptive vignettes. Writing exclusively for an upper-class audience of liberal-minded literati (the Strange Tales were circulated only in hand-copied manuscripts until the first printed edition was produced in 1766), Pu Songling recounts anecdotes involving bestiality, invulnerable penises, or dildos accidentally served up to dinner guests (stir-fried with lotus root) with the same frank curiosity he extends to a yarn about a giant killer turtle.

This sexual candour was expurgated from Herbert Giles’ first English translation in 1880, but is restored in the 2006 Penguin Classics selection (translated by John Minford). And there are other ways in which the Strange Tales can seem strikingly modern: the boundary dividing fiction from non-fiction is often hard to discern, and we need not squint too hard to see Kafka (who did apparently read some of Martin Buber’s German translations of the book) prefigured in Pu Songling’s depiction of a supernatural world that is subject to the same stultifying bureaucracy as the mortal realm.