Before They Began to Shrink

Nic Dunlop

Who owns the land where musket-balls are buried . . . ?

– Richard Murphy, The Battle of Aughrim

In 2010 I went to Ireland, the country of my birth, on a private errand and pilgrimage – I wanted to return something I felt wasn’t mine to own. My uncle had given it to me when I was in my twenties. He asked me if I was still interested in Ireland’s Jacobite war – his ancestors had fought on the Irish side – then handed me a small jeweller’s box that once contained a ring. Inside was a musket ball.

‘It’s from Aughrim,’ he said, winking at me. For years after, the musket ball sat on a shelf in my office in Bangkok next to Buddha statues and Khmer Rouge bank notes. It was only when my uncle died that I decided to return it to the battlefield where it belonged.

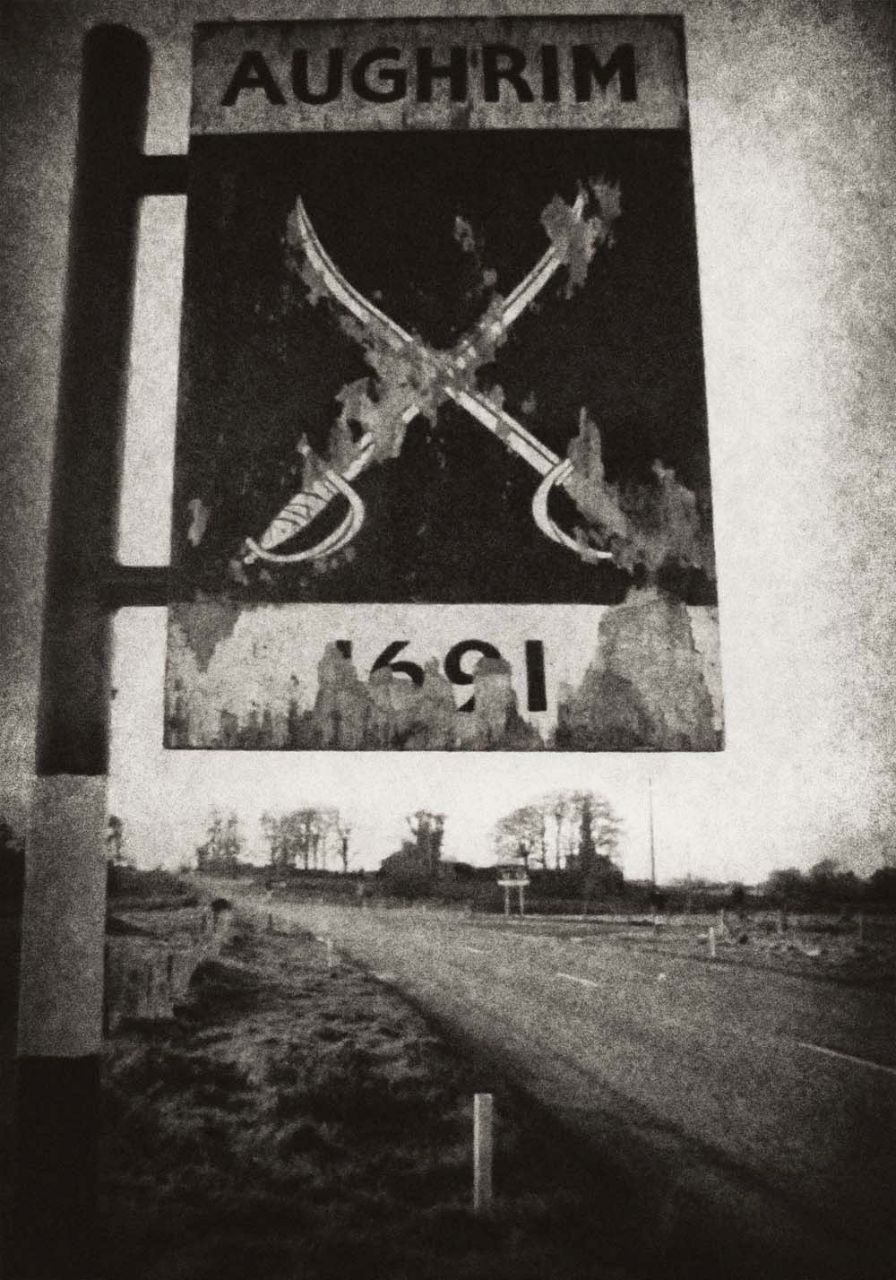

I don’t remember exactly when I first saw the signpost, but I always remember it as peeling and dilapidated. As soon as I’d see it, it was gone, but like the outline of a bulb switched off in a dark room it was branded on my mind’s eye: two crossed sabres, the single word ‘Aughrim’, and a date – 1691.

*

When I had to produce a history project for class in school, I chose Aughrim and threw myself into the research. I soon found there were plenty of books about the battle of the Boyne, but almost nothing about Aughrim. In the National Library in Dublin, I found a brief account published days after the battle – I still remember the thrill of holding those yellowed pages.

Every time my family went on our holidays we passed the battlefield. At my insistence, we would stop and explore. At the top of a hill I would survey the sweep of the battlefield and imagine thousands of soldiers marching through the smoke of battle. With no signposts to narrate my progress, I was free to wander in my own private world, caught in the spell of morbid enchantment. It was impossible not to feel the scale of the loss of life.

It seemed no accident that Aughrim remained largely forgotten. I came to believe it was a contrived amnesia, fed by a deeper shame.

*

The battle was the final episode of a war in Ireland that began in 1689, part of a larger continental conflict between the Protestant William of Orange and the Catholic King Louis XIV of France. The Irish Jacobites – supporters of the Catholic King James II and allied to Louis – were fighting for sovereignty, religious freedom and their lands.

The French commander of the Irish army, General St Ruth, decided to make a stand at Aughrim – he positioned the Irish Jacobite army along a hill, facing east over an impassable bog. On either end of the hill were two passes: to his left was the small village of Aughrim and a ruined castle that guarded a causeway; to his right the pass at Urraghry, bisected by a stream. According to the Rev George Story, who wrote an eyewitness account from the Williamite side, ‘nature itself could not have furnished him with a better’ position.

In the early morning of Sunday, 12 July 1691, a thick mist engulfed the Irish camp. Numerous candles flickered on temporary altars as Mass was held. The battle began at about eleven. Smoke billowed from the Williamite batteries as projectiles hissed across the bog at the lines of soldiers patiently standing in formation. The balls smashed into stone walls in explosions of sparks, rock and earth, throwing men into the air, creating instant gaps in their ranks.

The two opposing armies melted into one across a battlefield stretching over a mile and a half in length. ‘There was nothing but continued fire, and a very hot dispute all along the line,’ wrote another eyewitness. So intense was the fighting that the battle could be heard thirty miles away in Galway city.

The tide was turning in favour of the Irish as they continued to repulse attack after bloody attack. One Irish regiment pushed the enemy back across the bog with such determination they overran an artillery battery on the other side. Suddenly, it looked as though the Irish were on the verge of a great victory.

But then a series of disasters befell the Jacobites. General St Ruth was decapitated by a stray cannonball – his bodyguards threw a cloak over his remains and gathered up the body in an attempt to conceal his death, news of St Ruth’s demise soon spread down the line. The Irish defence began to waver. Irish musketeers at the castle ran out of ammunition and were forced to tear the buttons from their tunics to use as shot. The castle was overrun, and shortly after the cavalry on the left flank retreated, abandoning the infantry to face the enemy alone. The Irish positions began to collapse and panic spread.

Thousands were hacked to pieces before they could reach the relative safety of the bogs further west. Few prisoners were taken and most were executed, their bodies left to rot where they fell.

*

The day after the battle, William’s army set about gathering weapons and stripping the dead. Graves were dug and religious services held. The Williamites then marched on to Galway, leaving the Irish dead where they fell. Their bodies lay strewn across the countryside for months afterwards, ‘like a great flock of sheep.’

The numbers killed at Aughrim that day will never be known. It is generally accepted that the total was somewhere in the region of 4,000 Irish and 2,000 Williamites; almost double the number of casualties on all of the D-Day beaches combined.

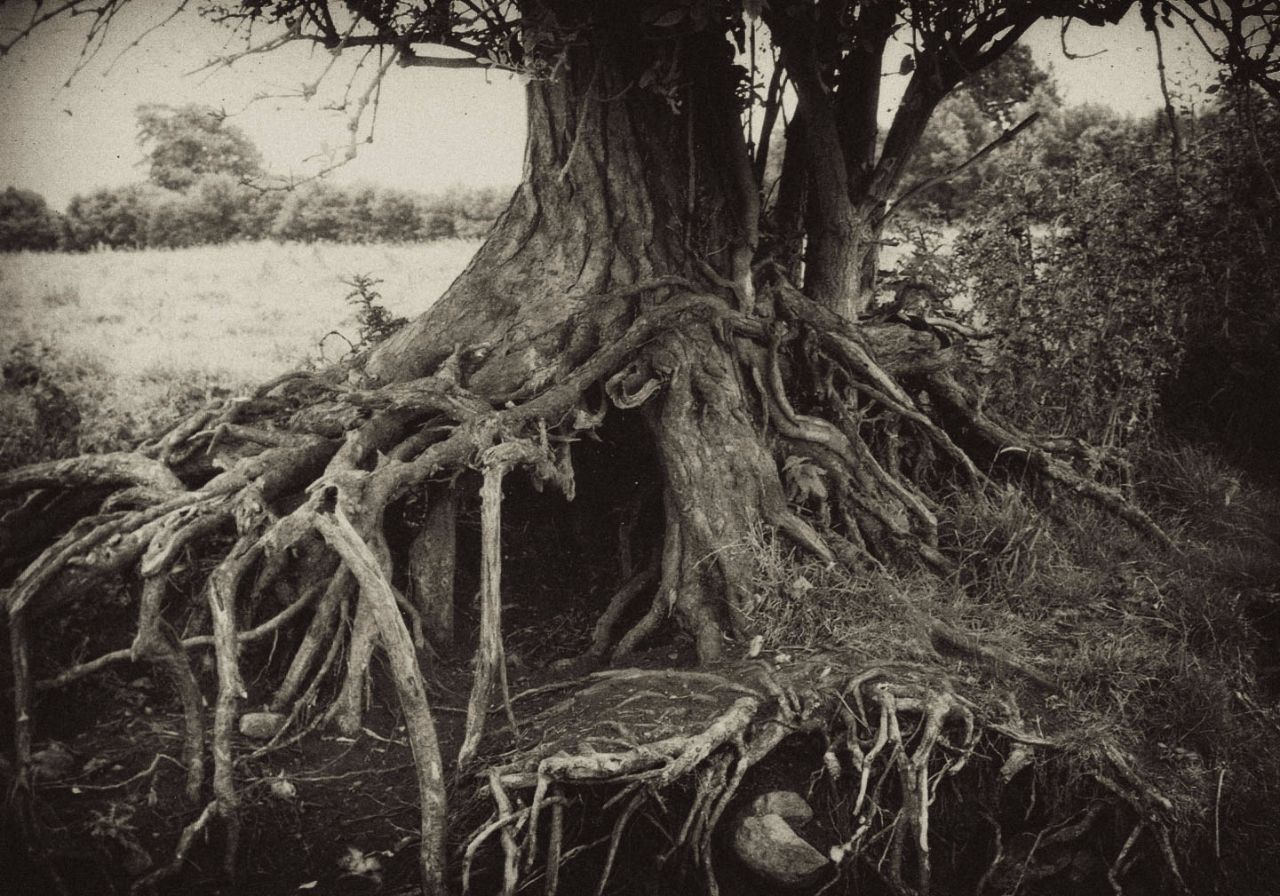

Today, the spot where St Ruth was killed is marked by a single blackthorn tree in the middle of a field.

*

Aughrim was where I began taking photographs. It was an early beginning for a career that took me to places of upheaval around the world, which often prompted questions of national identity. The photographs here were taken after eighteen years of living in Asia, returning to Aughrim to return the musket ball my uncle had given me.

Taking photographs of a seventeenth century battlefield presented a challenge – there is an inherent drama to photojournalism, but Aughrim’s bleak and empty fields were unremarkable. I was facing the limitations of the ordinary. I decided to take a series of images that might evoke the days of early photography and, with its imperfections, allude to the unreliability of memory itself.

I ambled over the part of the battlefield where the fighting had been so intense that soldiers ‘fought until the blood flowed into their shoes’. As a boy, that kind of detail thrilled me. Walking over the field now, all I could think of was the sight of blood on my own shoes when I slid on the streets of Bangkok after the army opened fire on protesters. I wanted to recall my boyish excitement, but all I could see was congealed blood in the grass.

Photographs © Nic Dunlop