Originally I had planned to get to New York the normal way, fly there, but then Harris and I had gotten into an odd conversation with another couple at a party. Our friend Sonja said she loved to drive; she missed having the time to drive across the country. And Harris said, Well, that figures.

What do you mean? we all said. Harris just shrugged, took a sip of his drink. He doesn’t talk much at parties. He hangs back, not needing anything from anyone, which of course draws people toward him. I’ve watched him move from room to room, running in slow motion from a crowd that is unconsciously chasing him.

‘Why does that figure?’ Sonja said, smiling. She wasn’t going to let this go. And maybe because it was her, so charming with her Auckland accent and big breasts, Harris suddenly laid out a fully formed theory.

‘Well, in life there are Parkers and there are Drivers,’ he began. ‘Drivers are able to maintain awareness and engagement even when life is boring. They don’t need applause for every little thing – they can get joy from petting a dog or hanging out with their kid and that’s enough. This kind of person can do cross‑country drives.’ He took a sip of his drink. Dogs were a hot‑button topic for us. Harris and Sam wanted one; I was ambivalent about pets in general. Are we totally sure about the domestication of animals? Will we not look back on this as a kind of slavery? But how to get out of it now when the world is so populated with dogs and cats that can’t fend for themselves? It’s not humane to just release them. It would have to be a group decision: No more pets after this. This is the last round of them. But that was never going to happen, even if everyone agreed with me, and literally no one did. Being anti‑pet (pro‑animal!) was one of my least winning qualities.

‘Parkers, on the other hand’ – and he looked at me – ‘need a discrete task that seems impossible, something that takes every bit of focus and for which they might receive applause. ‘Bravo,’ someone might say after they fit the car into an especially tight spot. ‘Amazing.’ The rest of the time they’re bored and fundamentally kind of . . .’ He looked at the ceiling, trying to think of the right word. ‘Disappointed. A Parker can’t drive across the country. But Parkers are good in emergencies,’ he added. ‘They like to save the day.’

‘I’m definitely a Parker,’ said Sonja’s husband. ‘I love to save the day.’

‘Wait, parking is exciting?’ said Sonja. ‘That seems counterintuitive. Wouldn’t driving –’

‘Think about it, hon, you have to get the angle just right –’

‘Okay, but are Drivers boring? I don’t want to be the boring, dependable kind of person.’

‘No, not at all,’ said Harris. ‘Drivers can have a good time more easily. That’s not boring.’

‘I want to be a Parker,’ Sonja said, pouting. ‘Too late,’ Harris said. ‘You can’t switch.’

At this point I peeled away from the conversation. Message received. Harris and Sonja were grounded, easy going, people who liked to pet dogs and have sex whenever. And I was a Parker. What he called disappointed was really just depressed. I’d been a little blue recently, not a lot of fun around the house. Not like Sonja. I watched the two of them chatting – his barrel chest and graying black curls somehow looked boyish and his level of animation was totally unfamiliar to me, I guess she brought that out in him. It wasn’t jealousy exactly; being a third wheel is my native state. Sometimes Harris will seem to have rapport with a waitress or a cashier and I immediately cede to them as a couple – I internally step aside and give my place to the other woman, just for a few seconds, until the transaction is over.

There was a small group of people dancing in the living room. I moved discreetly at first, getting my bearings, then the beat took hold and I let my vision blur. I fucked the air. All my limbs were in motion, making shapes that felt brand‑new. My skirt was tight, my top was sheer, my heels were high. The people around me were nodding and smiling; I couldn’t tell if they were embarrassed for me or actually impressed. The host’s father looked me up and down and winked – he was in his eighties. Was that how old a person had to be to think I was hot these days? I moved deeper into the crowd, shut my eyes, and slid side to side, shoulder first, like I was protecting stolen loot. Now I added a fist like a brawler, punching. I made figure eights with my ass at what felt like an incredible speed while holding my hands straight up in the air like I’d just made a goal. When I eventually opened my eyes I saw Harris across the room, watching. I could tell from his face that he thought I was being ‘unnecessarily provocative’. Or maybe I was projecting my parents onto him – that’s more something my mom would say – but he’s always leaned a bit traditional. On our second date I began revealing my peep show past the same way I always did, like a verbal striptease, until I noticed his face kind of shutting down. At which point I immediately began reversing the story, narratively putting my clothes back on, as it were, and minimizing the whole thing – a youthful misstep! Ancient history!

Now he touched two fingers to his forehead and I did the same, relieved. We’d done this saluting thing the first time we ever laid eyes on each other and across many crowded rooms ever since. There you are. He didn’t look away. Dancers kept moving between us, but he held on for a moment longer, we both did. I smiled a little but this wasn’t really about happiness; it hit below fleeting feelings. At this slight remove all our formality falls away, revealing a mutual and steadfast devotion so tender I could have cried right there on the dance floor. Sure, he’s good‑looking, unflappable, insightful, but none of that would mean anything without this strange, almost pious, loyalty between us. Now we both knew to turn away. Other couples might have crossed the room toward each other and kissed, but we understood the feeling would disappear if we got too close. It’s some kind of Greek tragedy, us, but not all told.

I wandered off the dance floor and into the master bathroom, washing my hands with the host’s facial cleanser. Of course it wasn’t too late to switch from Parker to Driver – anyone with a driver’s license could drive across the country. I could see myself pulling up in to the driveway with dusty tires, Sam running to greet me and Harris just standing in the doorway. He’d salute and I’d salute, but this time I’d walk into his arms, knowing I was finally home in a way I’d never been before.

By morning the idea had taken hold. Why fly to New York when I could drive and finally become the sort of chill, grounded woman I’d always wanted to be? This could be the turning point of my life. If I lived to be ninety I was halfway through. Or if you thought of it as two lives, then I was at the very start of my second life. I imagined a vision quest – style journey involving a cave, a cliff, a crystal, maybe a labyrinth and a golden ring.

‘I’ve driven across the country,’ said Jordi. ‘It’s not that great.’

‘It’s not supposed to be! Is a silent meditation retreat “great”? Do people hike the Pacific Crest Trail because it’s “great”? And this is even higher stakes because if my mind wanders too far I’ll crash and die.’

‘Oh god, don’t say that.’

‘But my mind won’t wander! I’ll be totally present all the way there and all the way back. And for the rest of my life I’ll tell people about this cross‑country drive I did when I was forty‑five. That’s when I finally learned to just be myself.’

Of course I was always myself with Jordi; she knew I meant be myself at home. All the time.

–

Harris had found an old foldout map of the United States and was tracing his finger across it. ‘If you take the southern route you can go through New Mexico and spend the night in Las Cruces.’ I was holding a plastic hairbrush and trying to focus on all the red and blue squiggles, but my eyes bounced off them.

‘Couldn’t I just put New York City into my Google Maps?’

‘But there are different ways to go. Different routes.’

He said I should take an extra week so the drive wouldn’t eat into my New York days.

‘Really? That’s more than two weeks without you guys.’ I had never been apart from Sam for that long. Each time they ran past us I tried to hand them the hairbrush; surely at seven one could be the steward of one’s own tangly hair.

‘Well, you don’t want to drive for a week and then just turn around and come home. You should really take three weeks to make it worth your while.’

‘Three weeks? No, that would definitely be too long apart.’ He was being generous because I had done a lot of childcare recently while he worked with his twenty‑seven‑year‑old protégée, Caro. Is protégée the right word? Ingenue, whatever. He’s a record producer, which is actually ideal – there’s no competition between us but he knows what an artistic soul needs. Early on I called her Caroline; Caro felt too intimate, like a pet name.

(‘Only the press calls her Caroline,’ Harris had said.)

(‘That’s fine. I don’t mind being like the press.’)

But it wasn’t just that he owed me childcare; Harris doesn’t have a lot of conflicted feelings vis‑à‑vis the domestic sphere. I didn’t either until we had a baby. Harris and I were just two workaholics, fairly equal. Without a child I could dance across the sexism of my era, whereas becoming a mother shoved my face right down into it. A latent bias, internalized by both of us, suddenly leapt forth in parenthood. It was now obvious that Harris was openly rewarded for each thing he did while I was quietly shamed for the same things. There was no way to fight back against this, no one to point a finger at, because it came from everywhere. Even walking around my own house I felt haunted, fluish with guilt about every single thing I did or didn’t do. Harris couldn’t see the haunting and this was the worst part: to be living with someone who fundamentally didn’t believe me and was really, really sick of having to pretend to empathize – or else be the bad guy! In his own home! How infuriating for him. And how infuriating to be the wife and not other women who could enjoy how terrific he was. How painful for both of us, especially given that we were modern, creative types used to living in our dreams of the future. But a baby exists only in the present, the historical, geographic, economic present. With a baby one could no longer be cute and coy about capitalism – money was time, time was everything. We could have skipped lightly across all this by not becoming parents; it never really had to come to a head. On the other hand, sometimes it’s good when things come to a head. And then eventually, one day: pop.

Harris was using a highlighter directly on the map and telling me I could always decide later to stay a few extra days.

‘That’s the great thing about driving; you can play it by ear.’ He could be generous like this for the reasons I just explained. Not me! I always wanted him back right on the dot – extended trips, school holidays, a child being too sick to go to school, these things run a chill down the spines of working mothers whose freedom is so precarious to begin with. Still, I loved this about Harris, how he always encouraged me to stay longer and have fun. I reminded him I had to be back by the fifteenth anyway. Of course, he said; obviously.

–

Jordi and I were sipping milkshakes; mine strawberry, hers chocolate. Once a week we meet in her studio and eat junk together. Usually desserts we’d eaten as kids but almost never again since we’d discovered the healing power of whole grains and fermented foods and how sugar was basically heroin. This was part of a larger agreement to never become rigid, to maintain fluidity in diet and all things. At home I baked high‑protein, date‑sweetened treats. No one knew about our medicinal junk food, are you kidding? Harris and Sam would both be jealous, each in their own way. Similarly, I never told Harris what I jerked off to.

‘But maybe you guys could role‑play it?’ Jordi suggested. ‘Do you guys role‑play?’

‘Never.’

‘We don’t, either.’

We decided then to tell each other exactly how a typical fuck played out in our marriages. We couldn’t believe we’d never done this before. If there was a good reason, neither of us could think of it.

‘Who initiates? You, right?’ I knew she was that sort of totally present, body‑rooted lover who felt like sex was a basic need.

‘Yes,’ she sighed, ‘it’s always me.’

‘I’m the initiator, too, actually, but only because I’m trying to get out ahead of the pressure.’

‘How often?’

‘Once a week.’

‘Wow,’ she moaned. ‘I wish I was having sex once a week!’ I laughed. We were so opposite.

‘I see it like exercise,’ I said. ‘You don’t ask yourself if you want to exercise, that’s the wrong question.’

‘You don’t exercise.’

‘I know, but if I did, I imagine it would be similar. I also don’t love getting in pools, by the way. Sunday nights! Packing for trips! Any transition. Whatever state I’m in I just want to stay in it, if that’s not too much to ask.’ It was, though, for a married person. Sometimes I could hear Harris’s dick whistling impatiently like a teakettle, at higher and higher pitches until I finally couldn’t take it and so I initiated.

I went step by step, demonstrating some movements, saying who put what where, how many times I came, how it ended.

‘Geez,’ said Jordi. ‘So many positions.’

‘Yeah, that’s more his thing. I’m completely inside the movie in my head. It’s like I have a screen clamped in front of my face.’

‘What’s on the screen?’

‘Oh, you know, I’m a gross stepfather getting a blow job from my nineteen‑year‑old stepdaughter, or I’m the stepdaughter, getting tucked in. Or I’m flipping back and forth between them. There’s a lot of special tucking in involving boners.’

‘A stepfather and she’s over eighteen,’ Jordi laughed. ‘Very legal.’

‘It’s consensual! They’re mutually obsessed with each other; that’s a big part of it. You probably just think about Mel.’ ‘You don’t think about Harris?’

‘No, I do. Same dynamic, but with an intern or assistant. Usually I’m Harris being seduced by her. She’s reassuring me that my wife will never know and finally I just let her suck it.’

‘Geez, I feel so unimaginative,’ Jordi said. ‘I’m just like, ‘Body feel good. Me want.’’

‘You’re present – that’s much better! A body‑rooted fucker.’

‘Is there another kind?’

‘Mind‑rooted.’ I pointed my thumb at myself. ‘But I’m hoping to be more like you after my trip. Now you go.’

‘Oh, it’s so boring compared to you guys.’

I was pleased she felt this way.

‘Just tell me.’

She took a sip of her milkshake and pulled her mountain of black curls into the hair band she always wore around her wrist.

‘Sometimes it starts when we’re asleep, we just kind of start having sex without even knowing it. So we’re half‑awake and sort of sloppy and then it gets more heated and . . . oh god, it’s not . . . sexy‑sounding like you guys.’

‘Keep going,’ I said. I was starting to have a bad feeling.

‘Well, often we’re in a kind of ugly position, like with both our legs wrapped around each other, kind of in this tight ball, and I really like my mouth to be overfilled so almost her whole hand might be in my mouth so there’s drool running down the sides of my face and we’re just, you know, humping, kind of like animals. I’ve actually thought about how ugly this must look, like two desperate cavewomen. Usually we’re too asleep or lazy to go down on each other or use a dick so there’s just, like, a bunch of fingering, or not even that, just grinding. Sometimes I will literally just hump her butt until I come, without even fully waking up. Sometimes I fall asleep with my fingers in her cunt and when I wake up they’re all pruney.’

I was quiet now, bludgeoned by this vision of intimacy. It wasn’t a matter of having lost at this conversation; I had lost at life.

It was almost midnight. Moonlight and lamplight came through the window and her sculptures gleamed around us. They were Jordi’s own body but morphed, ghoulishly skewed toward animals, cars, monsters, always headless, in wood or limestone or plaster. We wouldn’t see each other again before my trip.

‘You know you can just fly if you want,’ she said. ‘Are you saying that because you think I’ll crash?’

‘No, no, not at all. Just that if you don’t transform . . . that’s fine, too.’

I stared at her in the half‑light and she looked straight back at me.

‘I’m just making it harder for myself, aren’t I?’

‘Maybe.’

I came into the house my usual way, like a thief. I turned the lock slowly and shut the door with the handle all the way to the left to avoid the click of the lock. Took off my shoes. Rolled my feet from heel to toe, which is how ninjas walk so silently. I was often two or three hours late because I had trouble admitting that I was planning to talk to Jordi for five hours. But how could it be any shorter, given that it was my one chance a week to be myself? My heart was pounding as I tiptoed through the living room. I know the quietest way to wash up, too: picking up and putting down the cup and face wash with this technique where you pretend each thing is heavier than it is. Imagine the cup is made of brick, so that as you put it down you’re also lifting it up, resisting its weight – the opposite of this would be just dropping it, letting gravity put it down. When I walk past Harris’s bedroom I think glide, glide, glide.

When Harris comes in late he slams the door cheerfully behind him. He’s trying to be quiet, but not that hard. His mind is on other things, and why not? This is his house. Why behave like a thief? He doesn’t see how each moment can be made terrible if you only try. There can be a problem every second so that life is a sort of low‑grade torture. Then, when you are free, like when I was eating dessert with Jordi, it feels really, really good, like a drug high. So: grit, grit, grit, then: release. Joy. This works especially well for a life built around grueling self‑discipline culminating in glittery debuts and premieres. Grit, grit, grit, then: ta‑da! The thing that links the two states is fantasy. As a girl I fantasized about the perfect dollhouse, now I fantasize about the moment when I would finally reveal what I’d been making in the garage and be suddenly seen, understood, and adored – or at least get to stay in a nice hotel. These rewards really took the edge off life, carried me through the endless cleaning and cooking and caring and working. As a child I knew these weren’t just fantasies. One day I really would leave this house, these people, this city, and live a completely different life.

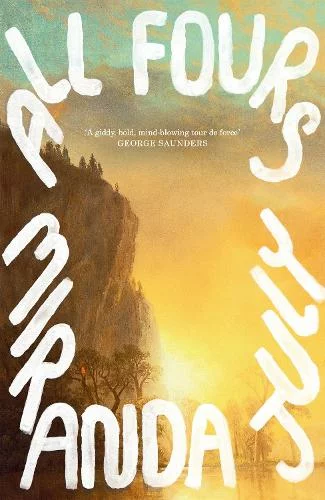

Image © Niamh Brannan