I drew the first chapter of my graphic novel in North Carolina. My stepfather has an old drafting table that I parked in the middle of my parents’ living room, flanking the television like a satellite. While I drew, I watched 90s movies like A League of Their Own that roused sleepy nostalgia. Nothing too exciting, nothing that would derail my hand or force me to jerk my head upward. Nothing with too much sex. Surprisingly, I only watched one Ken Burns documentary. [1]

My stepfather dropped the first ten pages of my graphic novel into a puddle of water and ink during a bout of frenzied cleaning. My eyes bugged out like an animal, and I ran to the bathroom. I remember heaving in anger and watching myself, thinking, ‘Oh.’ He cried in relief when I assured him that I could repair the small stains and smeared letters.

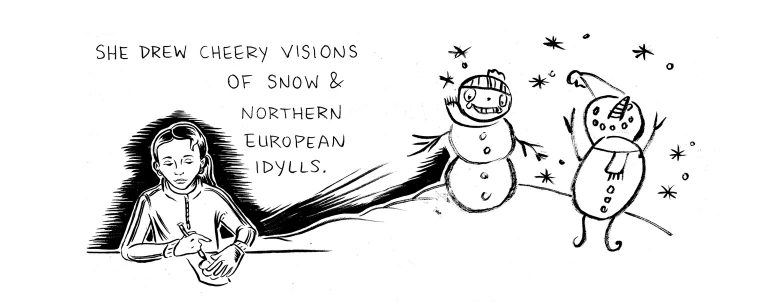

The passage with Haya’s snowmen was especially messy after the ‘dropping’. I begrudgingly whited it out and re-wrote into the blank space above her head,

‘She drew cheery visions of snow and Northern European idylls.’

We teach people that drawing is rooted in realism. A crosshatched nose is better than two dots. It seems like a lot of people have a hard time drawing noses because of the complicated angles and bumps. Noses are drawn and erased until the middle of the face is pulpy and raw. [2]

I loved the shaky weirdness of one woman’s drawings of forests, birds, and dream houses. She was eighteen and sometimes drew out the plots of Nigerian soap operas. After a few classes she joked, ‘You always say that everyone’s drawings are good.’ My general delight made me less credible. But I wasn’t lying: I do think all drawings are good. Yes, even the drawing of the overwrought, evil clown outside a tattoo parlor near my friend Lauren’s apartment.

One man came to the workshop and quietly set to work. He explained to me (if I understood correctly) that it was his first time drawing. He copied a leopard from a 1950s book of animal photographs that a friend had given to me. He worked on it for around two hours, delicately shading its spots. The leopard didn’t have much heft; it was sheer and ghostly. At the end of the workshop, he marveled at his work and left it with me. Gray levitating spots in my closet.

One of the hardest parts of writing a graphic novel is making all your letters look the same. Of course, I could do this in Photoshop or Illustrator, but I’m a purist, hence my Wite-Out resistance. So I use a T-square to draw guiding lines, because otherwise my letters shimmy up and to the right. Despite my best efforts, the lettering in my graphic novel changed from the beginning to the end. My writing became slightly smaller and shakier. You can’t stop the evolution of your hand, I guess.

Sometimes I want to reinvent myself as a nineteen-year-old wunderkind-boy-painter who makes big abstract canvases. Representation can be so stiff. I want to forget the little boxes and cutoff heads and speech bubbles and limbs drawn in heightened, deliberate exaggeration. I want to throw paint around, smoke cigarettes, and forget the boy, with a thin mustache, drawing a sunflower.

Drawn to Berlin: Comic Workshops in Refugee Shelters and Other Stories from a New Europe is available now from Fantagraphics.

[1] Actually it was produced by both Burns and Lynn Novick, who seems to get forgotten a lot, including by me.

[2] An eraser in German is ‘Radiergummi,’ which is a very cute word.