The group of us had flown by chartered plane from Toronto to Kangerlussuaq, in the extreme depths of western Greenland’s longest fjord.

Before boarding our ship, we were driven up, up, up until we could see the very edge of Greenland’s ice cap. From our vantage it looked vast and solid. There was no hint of the melting beneath the surface, the icy rivers eating through like turbocharged termites in an old wooden house.

Back at the dock, we queued for the Zodiacs, polite Canadians waiting our turns like we would for a rush-hour bus. To the right, our luggage was lifted down to the dock on flats by crane, then loaded into Zodiacs to be delivered to our berths. To the left, a caribou carcass leaned against a wall gathered flies.

Our ship waited for us just offshore – the ship that would take us down the fjord and into the Northwest Passage.

The excitement was palpable. We smiled shyly at each other. Strangers now, united in a dream of the North. On day one of an expedition, everything is possible.

My husband David and I threw our things into our berth and took to the deck to watch the glorious fjord slip away. The sun took its time, washing everything with warm gold. Beams of sunlight haloed the edges. Grand ancient rock glowed like burnished gold.

Exhausted by a day of travel, we fell into our blackened rooms and slept like nested kittens.

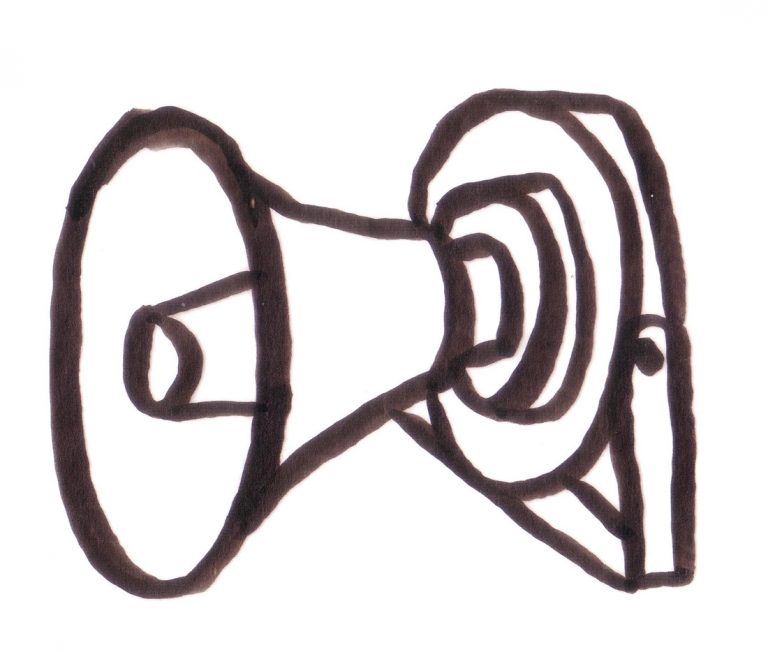

Much sooner than I would have thought possible, an abrupt loudspeaker bellowed from inside our room: ‘Wake up, wake up, wake up! You’re sleeping through beauty! Majesty! Get up and get yourselves on the deck!’ Too early, we stumbled our way into our clothes, the most outdoorsy things we owned, purpose-bought for this trip.

The ship cruised slowly through fields of ice. Shimmering blue and green in the endless sun. The pack ice sparkled like cut glass. We all piled eagerly into Zodiacs to get closer. To prove to ourselves that it was real. To touch the ice. Wave at fishermen. I wondered what they were doing all the way out here. Maybe we weren’t so remote yet, physically, despite the uneven ground on which my sense of place was trying to balance.

I didn’t quite have my sea legs yet.

I was uncharacteristically quiet. There was too much. My senses all firing at once.

Gulls too lazy to fish for themselves swooping the fishing boats. Our guide said something to the fishermen and they laughed, passing over an entire dried fish to be shared around.

Our guides showed us how to pull chunks of glacial ice out of the water and lodge them on the prow. Later, the bartender chipped off chunks and made cocktails with the ancient ice. Older than civilizations, the ice cracked and popped and melted as the booze and mixer hit it – a sub-Arctic symphony. It seemed too decadent for words.

Tiny communities hang on the edges of Greenland’s stoney cliffs. My cell phone picked up a signal from even the tiniest and most tenuous. I sent a flurry of tweets. I took it for granted that it would be like this all fourteen days we’d be at sea. Hubris, part one.

We lingered on deck and were rewarded with a breaching humpback whale. A fountain of a blowhole. The breach and the disappearing tail.

Up here in the Davis Strait, the golden hour lasts all night. The gold faded into rose as I stumbled to my blacked-out room. Morning would come soon.

Awake again before the blankets finished settling around me, and we were traveling up a fjord to see how close we could get to an active glacier. So close, close enough. Closer.

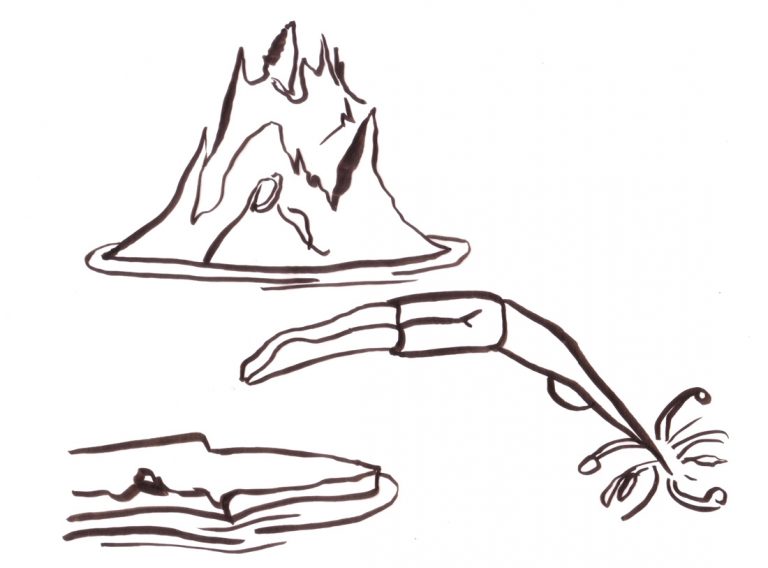

It looked like a perfect meringue the size of a city block. Our guides invited us to climb into the Zodiacs, and we inched closer and closer still. I couldn’t quite get my mind to accept that it could keep getting bigger. The city block grew taller. And taller. Skyscrapers of ice towered above us. Thousands of gulls dived for the plankton that clouded the water at the glacier’s edge, detached from the face of the glacier by the persistent tide.

And then it calved. Right there, in front of us. An avalanche broke off and fell into the sea. A massive rippling wave and we were riding those tiny boats like bucking broncos.

This is how the North made me feel my size with a new, more accurate relativity. I was a speck. I might as well have been part of the plankton buffet.

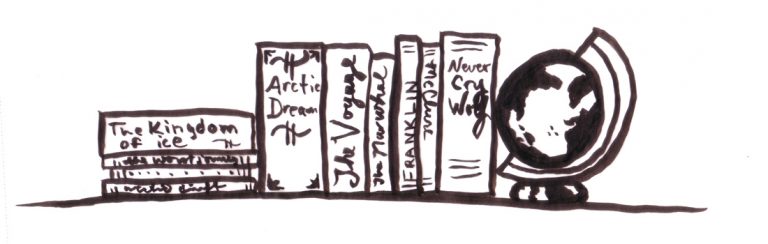

A full day at sea. This is where we left cell signal behind for the rest of our trip, but we didn’t know this, so we kept looking, reflexively, for the first few days. When our phones are just cameras, they last all day, easily. It is connection that eats up our reserves. Our hands itched with the desire to share the wonders we were seeing with the world. Yet it only took a few days to stop missing the Internet. We had to talk about a thing until somebody remembered it. Some disagreements had to be left undecided. No Wikipedia and no set of encyclopedias in the library. Plenty of books on adventures past, mammals of the north, seafaring birds. Inuit, Thule and Dorset. The voyageurs. The RCMP. Few people come north without a purpose that can only be achieved here.

Dovekies. Northern fulmar. Iceland gulls. Lapland longspur. Black guillemot. So many different birds. Some differences subtle, some unmistakeable. All made their lives here, in the polynya, an area of open water surrounded by ice.

Everywhere ice. Turning from blue to green to pure, blinding white. When the sun came out the shine was almost too much to bear, but I couldn’t look away. I never knew what sunblind meant before this.

A tabular iceberg more than two nautical miles across the face and even wider. The captain agreed to circumnavigate it. It went on for so long that most passengers became bored, returning to their cabins or the bar.

I felt smaller every day. Not diminished, but contextualized. I spend most of my time in places built to a human scale. Yet here, above the treeline, perspective had broken. I see why the crew felt the need to feed us so much. We had to build ourselves up so we didn’t disappear.

The scale of this place! Without trees, it was hard to understand just how massive the cliffs were. My only perspective was our ship – a ship that once seemed so large to me had become a speck. We were small, yet expansive. Something about this place filled me with possibility even as it put me in my place. Time spent in the North was time spent with my truest self. The lack of cell phones and the Internet helped, but they weren’t everything. The intensity of the unfamiliar was all-consuming. Voluptuous.

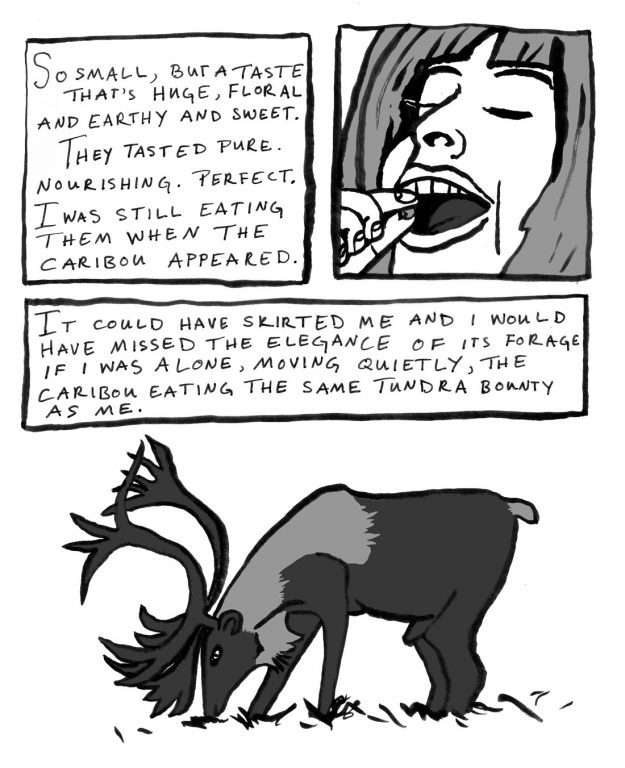

The landscapes were dizzying in their disparity. Rocks the size of cities. Flowers the size of beads, covering the tundra with vibrant colours. Spotted saxifrage. Cotton grass. Arctic draba. Moss campion. Alpine catchfly. Arctic mouse-ear. Dwarf fireweed. Whitlow grass. Alpine bistort. Prickly saxifrage. Arctic poppies. Tiny birch, growing low against the ground. And my favourite: nodding campion – flowers like purple Chinese lanterns, cleverly creating a warmer microclimate in the flower’s bladder to attract insects for pollination. Survival in the North required craftiness.

It doesn’t seem possible, but as much as the tundra was covered with tiny flowers, there were insects everywhere. A richness I didn’t expect. Warble fly. Ichneumon wasp. Mourning cloak. Looper moth. Non-biting midges and their adorably fuzzy antennae. Butterflies. Mosquitoes. Lice. Spiders. Two kinds of bee.

We crouched down and watched pollinators tumble across a bed of moss campion or drink from the dwarf fireweed. If you’re in a pinch, the dwarf fireweed is tasty and bigger than most arctic flowers. You could likely forage a lovely salad of it and sorrel. Maybe add some of the tiny berries.

Inuit drumming at the face of Executioner’s Cliff. I looked over and our friend Lynda was ecstatic, her entire body serving the sound of the drum. Her drum was talking to the island where she was born, and she was the conduit for the conversation. We were graced to witness the intimacy and joy of her reunion. Already a rarified place, she lifted it up, exalted, drawing us into her joy.

Later, Lynda tells us that it was the first time she drummed on Baffin Island. Born in Pangnirtung, Lynda grew up an urban Inuk in Ottawa. I could only imagine the way her heart must have sung, but she positively glowed.

The idea many people have of the North doesn’t include people. The texts that fuel many childhood dreams were written by or about white men. Explorers. Men of letters. Roald Amundsen, John Franklin, Jack London, Martin Frobisher, James Cook, Robert Service, Robert McClure, Pierre Berton, Henry Hudson and James Bay. In many cases, explorers were operating under Terra nullius, so they may have considered themselves to be settlers, not colonialists.

Yet this land was no Terra nullius. Inuit had a different way of living to the Europeans, coasting over the land, collecting as needed to continue their lives, leaving very little behind. Belonging to no one would have meant something very different to the voyageurs than to the Inuit. One in a series of catastrophic miscommunications that bring us to now. Inevitably. Like watching a train wreck.

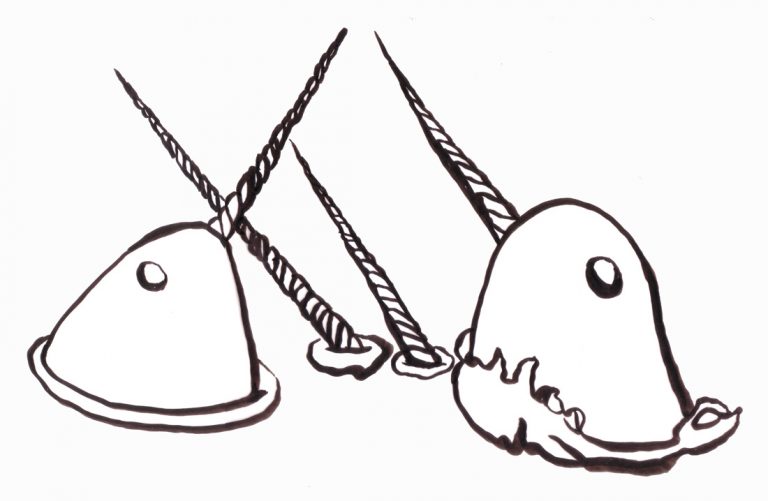

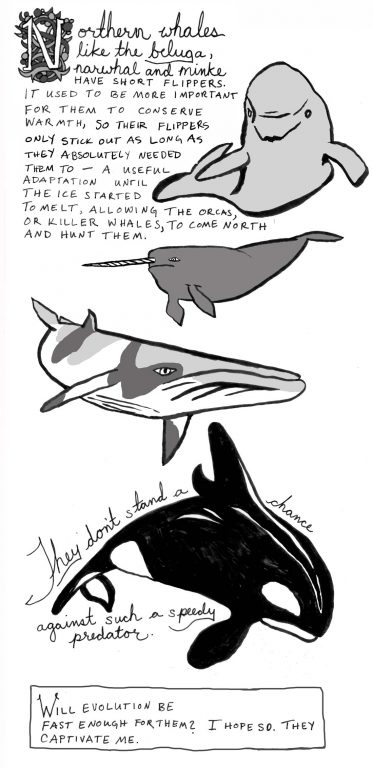

Morning brought a stunning fjord on Baffin Island. The sea was full of narwhal with calves on their backs. I borrowed a scope and saw two crossing their tusks, playfully, unicorns of the sea. They would easily disappear, perfectly camouflaged by their mottled skin, but for the need to breathe, and to let their offspring breathe.

Now we scrambled into the Zodiacs. We were watching blowholes from a distance. It was enough to be on the water and know that they were right there. We hung back, not wanting to crowd them. No tusk, but we saw their bodies skimming the surface as they breathed, looking like nothing more than a single massive sea monster. Something scribbled in the margins by ancient cartographers.

We held our distance and cut the engines, but it was too late. They weren’t fooled by our silence and they slipped away into the sea.

We took the Zodiacs to the north shore of Baffin Island for a late evening walk. Everything was golden, but most of all the yellow petals of the Arctic poppy. Golden petals were lifted up by fuzzy stems and it was all shot through as if glowing from the inside. I knelt down to admire each flower as our guides fanned out with guns to create a perimeter.

I looked at my hand and it glowed rippling gold. My skin shimmered. My hair was translucent. I looked at David in silhouette and his edges were on fire. It was as if we were being slowly transformed into stars. This moment lasted a long time. Hours.

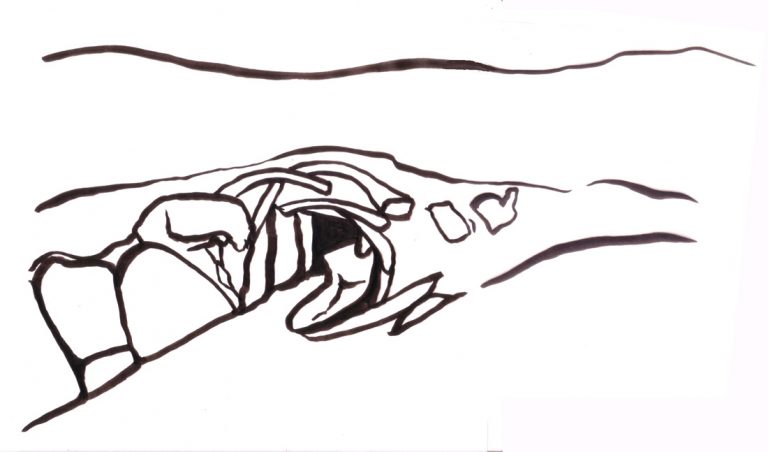

There was a bone city there. An archeological site, but our onboard archeologist got a permit so we could visit. Gently. We were not to walk on the dunes, or too close to the site. Eight-hundred-year old Thule foundations, remarkably intact. A curve in the earth shadowed by the curving bones of a whale. They formed perfect spines to stretch skins over. The pelvis formed the entrance. Each day, the Thule were birthed by the very whales that sustained their lives. It was so small. The Thule, a pre-Inuit people, were very small. I’m five feet two inches and I was a giant there. King Kong with impulse control.

In the morning, we were going to Pond Inlet. Somebody asked if there was a Tim Horton’s. The crew laughed. Soon we’d know why.

We chose to walk into town. Roads littered with bones. Red-throated loon. Long-tailed duck. Snow bunting. Sun shining through perfect cotton grass. A delicious morning walk, the long way.

Pond Inlet was smaller than I expected. Smaller than small. Of course, everything human-made feels small up here. Houses seemed especially tiny when I found out how many families lived in each one, and that tuberculosis is still a problem.

The community faced the mountains and the morning sun. The streets were awash with thin, clear morning light. Everybody smiled with warmth and openness. A man on an ATV tried to sell us each, in turn, a narwhal tusk. One man considered it, but he couldn’t bring a piece of a protected species back to the States, where he lived. I was secretly relieved when he gave up.

We were treated to a cultural demonstration. Inuit games! High kick, balanced hand. Headpull, fingers looped into each other’s cheeks. An ultimate tug of war. An elder lit the qulliq, or oil lamp. Singing. And then dancing. But the throat singing went right through me. Even as the girls playing were doing everything they could to make each other laugh and win the game, the sound got inside me. Guttural like a monster, like an angry sea, like the wind through rock. Like deep exertion. The sound moved through me and the floor and connected with the rock below.

I was still. The sound quieted the white noise I always carry within me. You know the kind. Where you don’t move at the same speed as the world around you. That was all gone – I was at peace.

And then the games were over, and I could feel the fidgeting slip back under my skin, into the pit of my stomach.

It was 2013, the heaviest ice in eleven years. It was starting to look like we had no chance of actually making it through the Northwest Passage.

We went for long walks, places our guides had never been before. It was starting to feel as though we were killing time, waiting on the ice. It felt good to walk on the shore, to stretch into the wind, to stop circling the deck like caged animals. Some passengers grumbled. They’d paid for the Northwest Passage and they wanted it delivered. I found poetry and justice in our potential failure, it seemed more like a real northern adventure than an easy passage would.

We stretched out with a nine kilometre walk through a moonscape. Gale-force winds. The lightest of us struggled to adhere to the path, not to float away into the sea. I put rocks in my pockets. Spiders everywhere. Complete lemming bones in an owl pellet. Foxholes. A family of snow geese. Tiny wild sorrel that tasted just like the big leaves in my garden. I continued to eat all of the plants. One of our Inuk guides told me that no plants up here could hurt me, but only some are traditionally eaten. I think I could tell which ones just by tasting them. So far, my record was solid.

Rough waters made for a very wet return. Every bit of exposed skin had been crisped by the wind. Ruddy. Raw. Dry clothes felt like they were saving my life.

The wind. Gusts up to 60 knots. Choppy water. Deep, rolling ship. I was grateful that our cabin was in the centre of the vessel, as we were not subjected to the worst of the weather’s effects. What rocked me to sleep tossed others onto the floor. I’d have wanted to be strapped in. The worst seas we’d seen yet, and so cold.

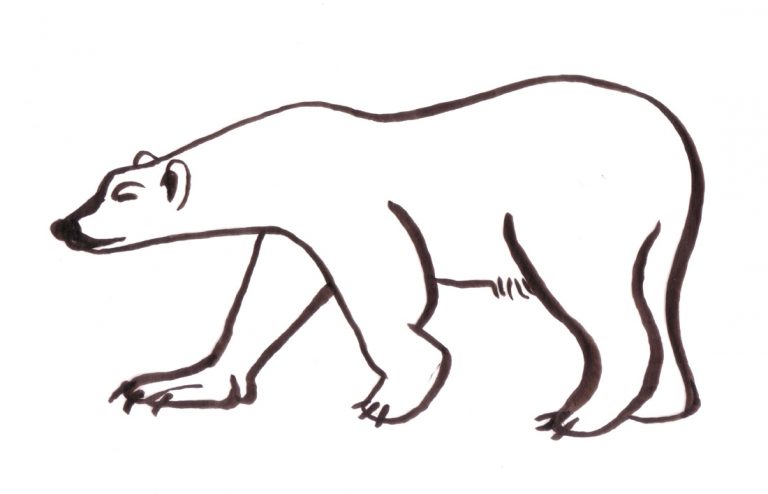

Eventually, the wind died down. The sun came out like a spotlight, shining directly on the slightly yellow fur of a polar bear against the crisp white of an iceberg. Such lazy ambling for such a grand animal. We all had time to watch. And someone spotted two groups of muskoxen in the distance. Just dots, really, but dots moving like a herd. They were dubbed musk-dots-en. Miserable conditions have their reward.

I sipped coffee on the deck, watching the wonders go by.

Eleven days at sea. Now that we were in the Arctic Circle, time zones changed nearly every day. Wake-up announcements did not change accordingly. It felt designed to confuse, to make this unfamiliar place even more disorienting. Maybe it was a ploy to keep us poorly rested and docile. We were a pretty well-behaved lot. Mostly Canadian, after all.

It was snowing when we reached Prince Leopold Island. There were 500,000 migratory birds here, but we couldn’t see them. Kittiwakes. Thick-billed murres. Snow and fog closed in on us. We could feel the wind change and the thick ice moving around us. Not being able to see made me feel even smaller than the Executioner’s Cliff had. Or the unseen had become larger, more expansive, in my mind. It’s always been that way for me. If I can put an edge to a thing, I can approach it, strategize. But I have to know what I’m up against.

We couldn’t land with all the ice and fog. Everything was grey. I was starting to feel anxious, stir-crazy. David and I played game after game of Scrabble while the rough sea washed over the ship. I imagined the creeping white noise explorers must have lived with on early voyages in these waters. I imagined the bickering. I breathed in, looked at it as an opportunity for contemplation, for meditation on my place in the physical and temporal world.

The weather closed in on us, so we had to give up. We had lectures instead, and a limerick contest. Something to focus on. Thoughts could get lost up here, meandering into the fog. It was quiet on board. Felt like a slog, like the drive from Toronto to Montreal. The endless grey became a boring highway with nothing to see. We passed Fury Beach, so-called because Sir William Parry was forced by ice to beach the Fury, a ship under his command, here in 1825. It felt like a place to give up, or to lose one’s bearings, physical or otherwise. I was having a little trouble hanging onto mine.

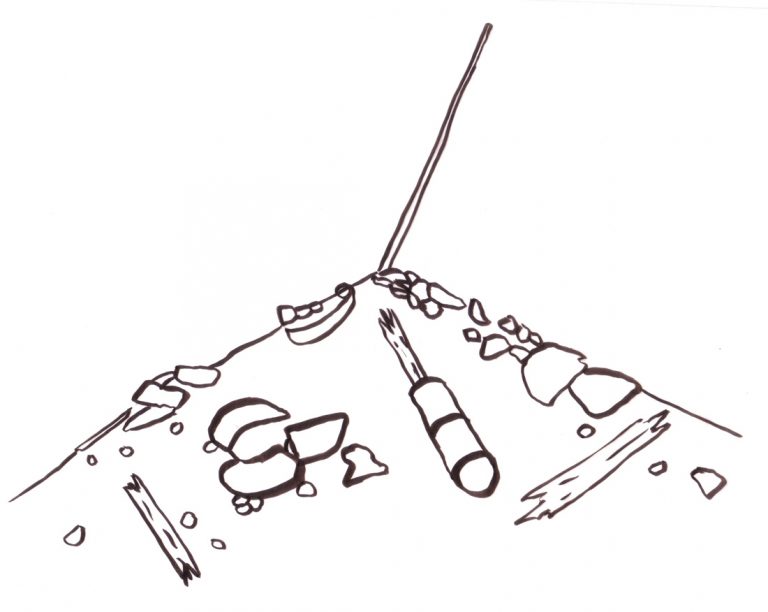

It was all of one degree Celsius when we landed at Fort Ross in the Bellot Strait. Fort Ross was the last new outpost built by the Hudson Bay Company in 1937. Eleven years later, they shut it down again because all the ice in the Strait diminished its usefulness. They left everything and it is still deteriorating slowly on the tundra. Once dropped or discarded, a thing stays on the tundra, maintained by the dry season and the preservative nature of ice.

Anything that’s been here fifty years is an artifact and can’t be moved. Beer cans. Scrap metal. Cooking pots. Nails. Girly magazines. All corroded or wrinkled by the water expanding their bindings. The durable ephemera of life. What we leave behind lasts much more than a lifetime. The trash on the tundra tells at least these two stories of man: one, a history of European explores who thought they’d found an empty place to claim for monarch and country, another the long history of Thule occupation, which was demonstrated by the intact foundations. The time between these radically different ways of life was small, like humans are small. Or at least, like I am.

And if we left anything behind, it would only be trash for a mere fifty years before it became another artifact here. Our cinematographer forgot his headphones on a beach. Even if he finds them next year, would it be right for him to take them back? How does the story continue, stay interesting for future archeologists, now that we’re careful not to litter?

It feels like we are outside of time, mere observers slipping through, even as we collapse time zones and chase history.

It was all here in case somebody was stranded. In case a storm swooped and a ship simply couldn’t navigate. Sailors from anywhere could stop here to rest and regroup. The food was very basic: you might not like it, but it would keep you alive. Which is all that matters up here, really.

The door is never locked. The difficulty of the climate provides tremendous opportunity for kindness. True kindness. A mitzvah. Not only does the recipient not know who was kind, the giver doesn’t know who will receive. Beautiful, really. I’ve never seen such a pure incarnation of the golden rule.

Our ship was ice class, but it wasn’t an ice breaker. The common impulse among the passengers was to press forward. Only our captain knew what was really at stake. Sometimes he humoured us, but only so far. He took us to the knife’s edge one day. Deep into the dense pack ice of Bellot Strait.

Pack ice covered nine tenths of the strait, but the Captain agreed to press forward as far as he safely could. Give us a bit of adventure to counteract the boredom of long days stuck on the ship. We bundled up and flooded the deck to watch the ice crack against the ship’s prow and close again behind us like a seal. We were giddy, like naughty children, getting away with something right in front of mom and dad.

When we could safely go no farther, we turned the ship and followed our own trail back out of Bellot Strait to more navigable waters.

On Bellot Strait, the Pacific meets the Atlantic for the first time since the Strait of Magellan. We wanted to see the currents colliding. The captain showed us the undulating seam in the water where currents from the two oceans met, equally matched, like a magnet’s power of opposition, pressing against each other tirelessly. In perpetuity. I imagined a trench on the other side of the earth, like parted hair, where the currents flowed away from each other. I wondered what it was really like. I vowed to remember to find out. I never have.

We were closing in on Beechey Island, the site of Franklin’s cairn, a physical manifestation of hubris. Franklin’s crew built a cairn, but, despite direct orders to use cairns to communicate things like where they were going next, the state of the crew, what led them to be lost in the first place – you know, useful stuff for potential rescuers, or at least those seeking closure for left-behind families – they didn’t leave any information. They didn’t even leave bad, shoddy or incomplete information. They left nothing. It could as well have been a trash pile constructed by bored crew members awaiting instruction. Humans have always liked to make piles. I do it all the time.

Later, a notebook was found. A notebook full of odd writings. Backwards words. Symbols without clear correlation to existing language. Perhaps the men had lead poisoning and were going mad. Recovered hair hints at lead while the bones tell us they definitely had scurvy. Severed arms and legs suggest that they were cannibals at the end.

I used to think that in the same scenario I’d be eaten early, because I am small and wouldn’t put up a great fight. Now I think that I could argue the cancerous tumours would render me unpalatable somehow. I could pretend that cancer was contagious. It seems like the kind of person who would turn to cannibalism could be manipulated by fear. In this Lord of the Flies world that I imagine, I just hope they don’t think of tumours as a delicacy. Then I’d be doubly screwed. ‘Dead too soon!’ they’d say. Well, if the cannibals hadn’t got her, the cancer would have. Small mercies, really.

This is what we will never feel on an adventure cruise. Whether we made it through the Northwest Passage or not, we would not be stranded. Satellites could find us and send help. The buffet was a bacchanal of cheese and fruit and meat. Endless plates, piled high, and as many desserts. The kitchen had food to exceed our wildest gluttony. We would never feel the desperation that would lead us to cut off each other’s arms and legs. To eat them. To decide who got the butcher’s knife first.

The seas were glassy when we woke up in Port Leopold. It was a balmy five degrees Celsius. We suited up and took the fleet of Zodiacs to shore.

Mist parted and we saw an amazingly intact Thule house. The Thule were so connected, following the whales’ migratory path. Whale fat burning the cotton grass wicks of their qulliqs, oil lamps used both to light their homes and cook their meals. Meat nourishing their bodies, preventing scurvy. Bones forming the architecture of their homes. This land was nobody’s and everybody’s.

Permanence and impermanence of the North. History is dense here, yet there are vast spaces where perhaps no human has ever walked. Hudson Bay Company. Thule. Franklin. We walked past the Thule archaeological site and there was a modern landing strip, complete with barrels of gas for refuelling and loads of spent gun casings. In the North, you can expect your things to be where you leave them. An honour system with such serious consequences that everybody respects it. Borrowed resources are replaced, hopefully in time for the next person.

The ocean was crystal clear. Sun cutting through. Everything was happening at once. And nothing. The moment stood. Discrete. The North is Canada. It’s who we are. We’re seen as a great barren land, but life is rich, diverse, fecund and utterly precious. Everything you need to know about Canada is up here. Everything that matters to our core.

Climate change is happening fast here. Indigenous knowledge about weather forecasting has suddenly become inaccurate. Generations of knowledge rendered useless, replaced by unpredictable weather behaviour. It’s easy to see the recession of the glaciers with the naked eye. It is significant. We could see the anomaly of the ice that hemmed us in, that was going to force us to be extracted at Resolute instead of Kugluktuk, set against the clear evidence of recession. Extreme weather and receding glaciers are both signs of global warming and climate change.

We saw a polar bear on shore and took the zodiacs to watch him move through the snow. He meandered off, still, we landed on the other side of the bay. We hiked into a rift cut through the limestone by an arctic spring, and at the source of the spring found an uncharted waterfall. The water had cut through layers of sedimentary stone, slicing through the most ancient history I’ve ever touched. Like the river valley, I was opening to the moment.

Snow falls. Water falls. I was careful, on this loose rock, not to fall. I focused on each step. The waterfall frozen like blown glass at the top. I refilled my water bottle in the glacial stream. It tasted like life itself, like bright hope. Crystalline. A bit mineral in a way that made me feel as though all my needs had been met. I asked myself if I’d ever really drunk water before this moment. If it was only water, why did I feel so complete?

We swam in arctic waters. We wanted to be clever, we tried to do tricks in the sea, but our bodies didn’t cooperate. They refused the mind’s signal and swam back to the ship. Our bodies swam fast. Now I know what it feels like to have the body switch into pure survival mode. The staff wrapped us in dry towels and gave us shots of vodka. Cold. Hot. Cold. Burning. Endorphins. Tipsiness. Skin raw, red. It tingled.

I wanted to go in again. I waited my turn, let everybody else go for the first time. By the time it was my turn again, I almost didn’t want to go back in. But I did. It’s just as good the second time.

The worse the weather got, the more animals we saw. A good eye can spot the yellow of polar bear fur against the pure white of the snow. There was a mama bear and her cubs on one iceberg. On another, a bear covered in blood tore into a seal, which was reduced to flesh, sinew and a crimson smear across the ice. A bearded seal reclined on another iceberg like Olympia on a divan. So luxuriant.

We took to land to walk at Radstock Bay. There was evidence of animals everywhere. Fox tracks. Fresh muskox tracks. We tried to track the muskox. Every time we crested a hill, it moved one more away. An arctic poppy pushed up through the snow. We narrowly managed to avoid stepping on it.

The ship met us on the other side of the island and against his better judgement the captain took us through dense ice to Beechey Island.

The ship buzzed with shared childhood imaginings. We pulled out our dreams to compare their scope. Arctic adventure is part of all Canadian childhoods. These wild, improbable stories suddenly felt attainable to us. Each of us had dreamt of testing ourselves against the wild frontier – of making a discovery and being celebrated by the country. And here we were. Going to breathe the same rarified air that Franklin breathed. We were in the footsteps of explorers and felt lucky to be there.

The island was covered in snow, though snow was no longer falling. There was no wind. Only the fittest handful of us were permitted to hike the mountain to the cairn. It was so steep that we began to sweat immediately. We were working so hard that we stripped down as we hiked. Tying our clothes around our waists in bulky layers. The ground was uneven beneath the smooth snow. With one step I fell waist-deep. The next, I jolted my hips by stepping too soon on rock, just covered by snow. Cognitive dissonance. The entire walk was like this.

After long climbing, the cairn emerged in the distance as a tiny pile. We had the sense that we still had far to go. We settled into marching across the pocked landscape in a close mass. At each end, a guide carried a gun in case bears appeared. They didn’t. All the wildlife could hear us coming. We weren’t exactly stealthy operators.

The cairn was a pile of barrels and stones with a mast jutting up at a jaunty angle. It reminded me of bonfires. How close is celebration to desperation, experientially? What are the analogues? How much of life is simply keeping busy to avoid the inevitable?

We took a minute of silence, clustered around the cairn, thinking about Franklin and his men. I thought about what it would be like to set off to opulent fanfare, leaving a wealthy wife and a safe life behind to try for a dream that may not even be possible. I was thinking of the vast north and its tiny plant communities, so tenacious, so clever and well-adapted. Are any of us that well-adapted to our environment? My inner thoughts were loud, clipping along. When I was still, they burbled up like hidden springs.

And then they dissipated. I was still with this place, on an Arctic mountain in the centre of raw, but not untouched, nature. My centre breathed easily there. I saw possibility spreading in the endless view. Every iceberg could be tableaux, primal scenes playing out in real time, as we threw our thoughts into history.

It was all the same there. Then collapsed into now and the future was everything and nothing. Being there, in the now, was enough for me. When my life is too much, I crawl back into this place. I am a tiny insect, slipping into a nodding campion for shelter, a brief reprieve from the work of survival.

I no longer see being small as a problem. To be small is to be in relation to a bigger world that is full of surprises. I am small in the context of the rich diversity of life on Earth. Earth is universally small. That I get so much pleasure out of my little life, however long it may be, is a gift. The context of the North is humbling and it makes everything okay, even when it’s not.