Summer in Japan is difficult. The evenings are alive with music, festivals, dancing, parades and fireworks – but these windows of abandon are only a brief respite from the agony of the daytime, ruled by heat and tyrannical humidity.

When I lived in Japan in my mid-twenties, I made it through the heatwaves by reading manga. High-school samurai, emo-driven battle-robots, Neo-Tokyo biker gangs. A deeper interest in Japanese literature followed, and as a translator and reader I’ve since immersed myself in a literary scene that is incredibly diverse and creative. Here are ten works of Japanese literature worth spending your summer on.

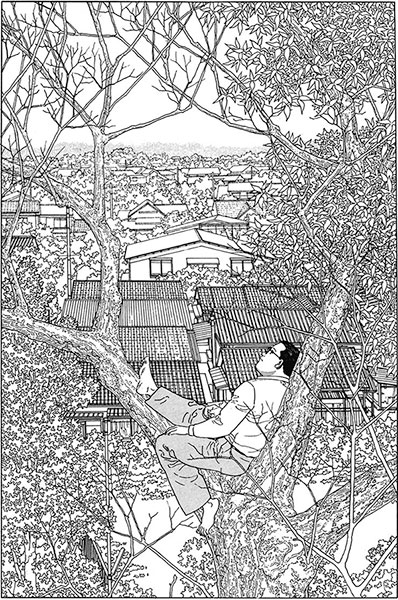

Away from the inhuman bustle of central Tokyo stretch miles of conurbation: self-contained urban villages linked by labyrinthine alleys, streams, parks and temples. This is the understated, quotidian backdrop of The Walking Man, one of the most arresting comics I have ever read.

Each of the short stories in this linked collection begin with a man leaving his home with the sole aim of getting lost. He walks his dog and finds a fallen birds’ nest; he leaves a bus to explore a temple glimpsed from the window; he climbs a tree barefoot to free a toy plane stuck in its branches. The comic embodies the Japanese concept of ma – emptiness, pause, the negative space between intervals of movement or sound. This same aesthetic sensibility informed legendary anime director Hayao Miyazaki, who said, “If you stay true to joy and astonishment and empathy you don’t have to have violence and you don’t have to have action.” The Walking Man is full of such quiet stories, led by wonder, curiosity, a desire to see, to feel and to be.

This linked collection of dark, unsettling tales opens with a woman visiting a bakery to a buy a strawberry cake for her son’s birthday. ‘How old is he?’ The baker asks. ‘Six,’ the woman answers. ‘He’ll always be six. He’s dead.’

Yoko Ogawa weaves obsession, murder and loneliness through a series of domestic tales that are short, unresolved, but never slight. The aforementioned baker was traumatised by losing her mother at an early age, but the discovery of an abandoned post office stuffed full of kiwis helps her eat through her sadness. The kiwis were grown by an old woman who has a macabre secret buried in the vegetable patch. A tailor creates a garment for a woman whose heart has grown outside her body, and a woman visits a museum of torture to imagine new things to do with her boyfriend. These stories exist in a vague limbo, unmoored from any specific time and place, which strengthens their uncanny, unsettling impact. All written in the same light-touch prose as Haruki Murakami or Hiromi Kawakami.

In these three fantastic tales, the supernatural intrudes on the lives of isolated young women. Kawakami watches, unhurried, as each situation plays out. ‘Record of a Night Too Brief’ follows a woman through a night of waking dreams with a shrinking girlfriend, inquisitive kiwi and transformations into horses and pearls. In ‘Missing’, family members keep disappearing, only to return as ghosts visible to the youngest daughter of the family. The novella at the centre of the collection is A Snake Stepped On, which launched Kawakami’s career in Japan, rather than the novel Strange Weather in Tokyo which brought her international attention in English.

Although Kawakami has cited Gabriel García Márquez and JG Ballard as influences, her stories feel as close to folklore as magic realism. Dream logic rules the action, but it never strays far from Kawakami’s central concerns – decay, alienation and female sexuality, along with the porous barriers between the world of animals and humans, reality and magic.

Ryu Murakami’s deranged satire follows the escalating guerrilla warfare between two groups of outsiders. Six feckless young men obsessed with karaoke, drinking and women waste their days drinking One Cup Sake and dancing on the beach. Six obasans or ‘aunties’, divorced women in their thirties who have been sidelined by society, chat about their clothes and their office flings but never really listen to one another. After one of the men stabs an innocent obasan in the street, her gang decides to take revenge.

Benjamin Seche, for The Sunday Telegraph, was probably right when he wrote that every time Ryu Murakami publishes a novel, ‘the people at the Japanese Tourist Board must hang their heads in despair’. Like Chuck Palahniuk or Brett Easton Ellis, Murakami approaches the dehumanising effects of modern life through provocative, uncomfortable frames and hard-to-love characters. His Tokyo is corrosive, ‘so crammed with stuff that it was difficult to see the reality,’ and filled with broken characters in love with pop music and TV dramas, but completely devoid of empathy or self-reflection. This is a trashy novel, violent and hyperbolic. But it’s also hilarious, and hard to put down.

Convenience Store Woman is a novel about finding your place in the world and having to fight to keep it. Keiko is a misfit, a lifelong loner, but she finds acceptance, purpose and happiness in her role as a convenience store worker. However, her family and friends have different ideas about what a woman in her thirties should be doing with her life.

Murata, who worked part-time in convenience stores for eighteen years, finds much humour in this dynamic. Keiko is contentedly single, uninterested in sex, working what appears to be a dead-end job with no hope of progression to a ‘better life’. But she is happy, and it is her family, with their ‘normal’ jobs and relationships that are neurotic and miserable, agonisingly aware of what others think of them. Murata can be scathing about conventional Japanese values, and she extols the quiet defiance of her oddball narrator as she creates a life on her own terms. ‘I don’t write novels to criticize,’ she has said. ‘But as an author, I try to describe very precisely.’

Satoshi Kon is best known as the director of the animated films Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress. These combine stunning visual storytelling with complex, metafictional plots. You should go check them out.

But before his directorial career took off in the nineties, Kon was a manga artist. His detailed, dynamic style owes a lot to his time spent as an assistant to Katsuhiro Otomo, the creator of Akira. But Kon’s personal work is mind-bending in its own way. My favourite Kon manga is Opus, both a thriller and a metacommentary, driven by the author’s anxieties about the serialised manga form. In it, a burned-out manga artist decides to finish his comic series by killing off one of its main characters. The character has other ideas, however, and steals the artist’s final pages, pulling the writer into the collapsing universe of his own fictional world. The ending is ambiguous, and based on a missing chapter found after Kon’s death in 2010, which provoked more questions than it answers. Nothing could be more fitting.

Yokoyama’s goal with Six Four was ‘to set the benchmark for the Japanese police procedural novel; examining the relationship between the main character and the crime, his working environment, the friction between him and the organization for which he works, and from this the wider, more harmful elements in Japanese society’. Commercially, the novel was a smash, selling a million copies in six days when it was released in Japan, and it has found critical and commercial success in translation.

And yet it is hard to explain how a six-hundred page doorstop about police bureaucracy and departmental infighting over a cold case so gripped and moved me.

Yokoyama’s detective Mikami has an obsessive attention to detail that reflects the author’s own work ethic – Yokoyama was hospitalised in 2003 after a mammoth seventy-two-hour writing-and-editing session. This obsessiveness produces a tightly-plotted murder-mystery that builds to a wonderful twist, and a world of almost two-dozen characters, each distinct and driven by their own motives, which feels sharp and real. This is a revenge thriller, but it’s also a metaphysical reflection on silence and loss, a study in professional self-worth and a meditation on personal identity.

Lost Japan was the first book written by a non-Japanese writer to win the Shincho Gakugei Literature Prize. The author, Alex Kerr, fell in love with Japan when his father, a naval officer, was posted to Yokohama in the mid-1960s, and the book charts his life-long passion for the country, its language and its culture.

Kerr is a knowledgeable, warm and endearing tour guide through Japanese art, calligraphy, kabuki theatre, the interplay of Japanese and Chinese cultures, and iconic places like Kyoto and Osaka. Kerr managed to gain what was, back in the nineties, unprecedented access to the closed worlds of the Japanese arts, and his obvious passion for his material is infectious.

Dogs and Demons is the polemic to Lost Japan’s paean – no less entertaining or lopsided in the author’s treatment of his host culture. What is striking is that these two views on Japan were written by the same man, published only a decade apart, and track an outsider’s changing perspective on their chosen home. In this follow-up Kerr unleashes a barrage of criticisms at Japan for its short-sightedness and lack of respect for its own culture.

Taken singly, Lost Japan is best read ahead of a fun week in Japan. Dogs and Demons is better if you’re a jaded English teacher in Tokyo, looking for confirmation of your unease in a strange country. Though both books are written from narrow, outsider perspectives, taken together they are a fascinating portrait of one man’s relationship with Japan: the rose-tinted wonder of a neophyte slowly turning to frustration and disillusion.

Yasunari Kawabata was the first Japanese author to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he was awarded in 1968. He is best-known known for his austere and lyrical stories that leave much unsaid. Kazuo Ishiguro, a great admirer, says his novels ‘offer experiences unlikely to be found anywhere else in Western fiction’. Unlike the pop-culture savvy of authors like Haruki Murakami, Kawabata’s stories focus on the tensions and dramas of closed worlds, like that of the family in The Sound of the Mountain, or the geisha community in Snow Country – my personal favourite.

A Tokyo dilettante begins a careless affair with a young geisha in a mountain resort, but soon finds himself returning year after year, bewitched by the doomed relationship and the wintry landscape. The novel’s frail human drama feels surrounded on all sides by the natural world, by emptiness and silence.

It is a tragic story, but never feels bleak or nihilistic. Kawabata’s work might best be described by the phrases in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, where he explains how the Zen disciple ‘departs from the self and enters the realm of nothingness. This is not the nothingness or the emptiness of the west. It is rather the reverse, a universe of the spirit in which everything communicates freely with everything, transcending bounds, limitless.’

Photograph © halfrain