Whether or not I did the right thing – whether or not I was just being a ‘good friend’ – whether or not I was lying when I said it was convenient for me to feed a cat for two weeks in an apartment a thirty-four minute walk from my apartment – whether or not I genuinely wanted to be the sounding board for the serialized updates of his break-up (what she said or did not say, what he accidentally texted, what he can infer from her most recent Tweet, Instagram or Tumblr post) – whether or not I, to some degree, relish his suffering – whether or not he is, as she said, unable to care about anything that is not happening directly to him and whether or not I agree with her – whether or not his narcissism and/or solipsism is inextricable from his character – and whether or not my inclination toward his narcissistic and/or solipsistic company reveals something sad about me – and whether or not I even enjoy his company or have just become habituated to it – whether or not, in short, I am or he is or we are both terrible people, and how terrible we may or may not be – all of this is still debatable.

Nathan and I met as undeclared majors of the late, late twentieth century after he failed to be exempt from Intro to Creative Writing. (The office hour plea: I’ve already been introduced, a ratty stack of pages as his exhibit A.) His stories were the predictable homages in the style of an Important Male Novelist, often featuring a Russian exchange student named Nikolai, a barely-disguised Id: The women is bad, Nikolai said, and we must not say so, but always remember, she is, all the she, is bad. He was commended for creating such a rich, opinionated character, but not by me. My notes on his submissions were all a variation on: Why should I care His notes on mine (gruesome crime fiction with unintended religious overtones) were usually arguments against my most recent notes for him. And I don’t remember why or how because I no longer understand the state I was in back then (heartsick over the idea of Jesus the way that other girls were heartsick over the idea of River Phoenix) but somehow this was the beginning of Nathan and I sleeping together, episodically, for the next ten years plus.

I was the type to wander a Rite Aid alone and empty-handed, for hours – a favored pastime of a teenager wondering why a belief in Jesus no longer feels satisfactory or even real. I stared at nail polish removers and thought about how I’d never be a youth minister. I compared nutritional supplements while considering the conditional and imperfect nature of human-on-human love. Even attempting to imagine ever having a feeling at all comparable to the infallible devotion I’d had (or fabricated, depending on your perspective) with The Son of God was like searching for a needle in a haystack while suffering from a severe hay allergy and knowing, all the while, there is no needle.

A few weeks after I first met Nathan we were in a poorly lit park at dusk, and I was explaining how I got that lopsided cross tattoo on one ankle and the shaky JC in a heart on the other, and I know it’s trite to remember that he pushed a lock of hair behind my ear and grazed the back of his fingers against my cheek, but that is what I remember happening so that must have been somehow important to me, and maybe that was the moment I accepted Nathan as someone who had a position in my life, a right to it, a tenure in it. And I probably believed, back then, that he was listening intently to that story of my teenage re-commitment to Christ which had happened after lights out during a youth group retreat. Three girls from my cabin and I snuck out to the little chapel in the woods where we all confessed to occasionally doubting the validity of The Bible and the existence of God and sipping from a water bottle of vodka at the Sophomore Spring Fling the previous April, and Sherry Evans even admitted to a blow job and we confessed those and other sins, together, aloud instead of in silent prayer, and we knew that Jesus would forgive and completely forget – at least, that was what the youth pastor had said, that if you were to ask Jesus what sin he most recently absolved from someone, Jesus, our Lord and Savior, would just look at you, dumb as a pancake (that’s how he’d said it) he’d look at you dumb as a pancake and say, I don’t remember. And since this was what Jesus did, I knew it was something I should also strive for (What Would Jesus Do was always the question) but I could never un-hear Sherry Evans saying she’d given someone a blow-job (and who?). But then we gave each other tattoos with a sewing needle and india ink and some of us cried out of joy or pain and we all did that kind of praying where you have your arms out, palms up, face up, eyes closed, swaying, murmuring words or whisper-singing and I remember thinking about how I looked like a picture of a perfect Christian, like those people in the commercials for gospel music CDs and I wondered if anyone in those informercials had ever given anyone a blow job but I immediately asked for forgiveness for having this thought, but had it again so I had to ask forgiveness again.

When I told Nathan this story I was trying to cultivate an air of mystery to match his air of mystery and I probably believed he was so impressed by it that all he could say was, Wow, and start making out with me, but when I referenced the re-commitment and tattoos some months later he sort of nodded and looked off and I knew he probably hadn’t been paying attention, that he was just waiting for me to be done. Maybe I believed he had that kind of amnesia that Jesus supposedly had, that our present overshadowed whatever it was that I was before we met, but after Mom met Nathan on Parents’ Day she said, quoting Paul, Honey, bad company corrupts good morals, and I knew what she meant but I told her she didn’t know him like I did.

I hope you’re right. I sure hope you’re right, and I knew she meant, you know. . . Hell.

It is true that Nathan was (and maybe still is) ‘bad company’ but that was what had made him good company to me – I needed bad company to keep the bad in me company. And despite several bad incidents during and after college from which it seemed Nathan and I would not recover (canceled plans and harsh words and his guitar thrown down a concrete stairwell) we did, somehow, always, recover. I once tried to rationalize that his name meant Giver, according to a baby names book, and I believed that his inherent generosity would eventually become apparent, that he would grow into that name the way some kids have to grow into their ears or feet and I should just be patient. But then I realized that names are just given, not earned.

It’s clear now that Nathan and I have always had just enough respect for each other to withstand a mutual disrespect.

I hadn’t heard his voice over a phone in many years (we had changed from phone-call people to text/email/comment people as the times had accordingly changed) so when he called that afternoon and said, Nikky! What’s going on? I just said, Nathan, what’s wrong? because I am not the kind of person who can tolerate these kinds of things.

Oh, I’m fine, he said, just wondering if you could take care of Echo while I’m out of town for a couple weeks.

And I surprised myself when I said, Sure, of course, and he said, Really? You’re sure? because I’ve been in the habit of finding some extenuating circumstance blocking me from doing even the smallest of favors, but I said, It’s no problem – I’d love to, and I knew I wouldn’t really love to, and I knew it was out of character, but lately I was wondering if there was a way out of my character and I figured this wasn’t the worst place to start. We hadn’t seen each other in several months, at least – maybe since that night at the Ethiopian restaurant when I told him I wasn’t going to have sex with him anymore because I’d decided that a sex life was a waste, a liability, a bore.

I don’t want kids. I’m tired of boyfriends. There are other pleasures in life.

He was either listening or making his I’m Listening face. A single lentil clung to his lip.

Do you want me to tell you what I think?

I was surprised he’d asked for permission. The lentil was still there.

No, I said.

Actually there was another meeting after the Ethiopian dinner – a spring day in the park, a bottle of wine, a long talk that reminded me of those long talks in dorm rooms and quads that had cemented our friendship. He’d told me about how well things were going with Analiese and he seemed remarkably genuine about it, settled, not at all like the Nathan I’d always known. I asked myself something that I have been asking myself ever since: Can people ever really change?

I haven’t even slept with anyone else since I met her, he said, and I don’t even want to.

There’s no way to say this nicely, but the truth was that Nathan and I would often have a little sex while one or both of us were in ‘committed relationships’ with other people, but only a little sex and not for any good reason more than habit and it’s hard to break habits, everyone has a few, and if it’s just smoking you can smoke and say, Oh, here I go with the smoking again, I know I shouldn’t but I just do, but if you have a low-grade, persistent infidelity habit there is no low-grade persistent infidelity section in a restaurant and there is no patch for kicking your infidelity habit and there is almost no socially acceptable way to talk about being unable to stop yourself from having a little sex with a person who is not your Publicly Declared Sex Partner.

That day in the park, however, I was still on my celibacy kick, smug like a juice faster, and even though we later went to his apartment to watch a movie, we did exactly that and I fell asleep on his couch and he went to his room and I woke up in the middle of the night and let myself out. Since then, many months and a few seasons had passed with us saying nothing to the other aside from a texted quip, a like, a comment.

You want to know the truth? (This is Nathan, again, on the phone.) Analiese broke up with me and, to be honest, I’m in a bad way. I really need to leave town.

I’m mostly sure that a ‘good friend’ should get no pleasure from hearing a ‘good friend’ say he has been dumped and is in a bad way, but Nathan had always seemed so invincible to heartbreak, and baffled by the ones I’d been through – but still, I felt embarrassed by that small, reflexive smile that came when he said he was in a bad way and I tried to rationalize that smile by thinking I was just pleased to be the friend he called for emotional and feline support, that maybe our ‘friendship’ was more than a shared tendency toward combat and a bit of detached sexual attraction. Maybe, somehow, we also had a real place in each other’s lives since he was trusting me with the life of his cat and plants, these lives he wanted to keep alive – but, no – I knew I wasn’t his first call and he wouldn’t have been mine. I knew and still know and can now admit that I smiled because Nathan had finally been broken.

It came out of nowhere. He sounded like a televised local reporting a tornado. Everything was perfect and then, just like that. . . Boom.

When I stopped by to get the keys and I found him half-drunk and glassy-eyed and chain-smoking though it was barely past noon. So it had happened. He had cared more about someone than they could care about him, and in a way I was seeing history being made, though just the minor history of one man becoming more human.

I’m sorry you’re going through this, I said. And, the thing is, I was, I think.

He didn’t say anything and then he said, Well – and he started to say something else but stopped and I almost asked him what he was going to say, but thought better of it. His face was bending like he might actually cry, and I’d never seen him cry except for that one time we took mushrooms but that didn’t really count, and he covered his eyes as if to turn them off so I took this blind moment to smile, again, but that pleasure came link-armed with guilt – guilt from being pleased by his pain, and that guilt, that by-product of the Jesus years, grew stronger and I know I cannot be held responsible for the guilt-pushed decisions I sometimes make, because it complicates feelings, or makes me want what I probably don’t want or distracts me with what I should want to do, or should at least want to want to do. This time the guilt made me listen for the next several hours and two bottles of wine as he ached over what had been so good, so perfect, and how could she give it all up and what had he done wrong and why and why and why.

For friends I can more easily call friends, people with a less complicated track record and a more developed sense of humanity, I have often been that crying shoulder, that good listener, and it’s true I once considered a career in psychology or social work or some form of clergy before I dropped out of college and stopped believing in God – and I don’t exactly read self-help books, but I almost do, and I’ve undergone various kinds of therapy, so my vocabulary includes ‘attachment styles,’ ‘boundaries’ and ‘emotional dysregulation’. So this was what I thought of while Nathan talked about whatever he was talking about, a sudden trip she took, a lie he believed, her saying he was over-reacting and him saying she was under-reacting and something that he wished he could take back, something involving her mother or his mother, a wrong number called – something, I don’t know – because I was distracted by the novelty of seeing Nathan have such real expressions on his face, a rare vulnerability. He kept saying I’ll be honest with you and Truthfully and asking if he could tell me something and then telling me something, but I was tracing our history back to the weeks just before I dropped out of college, how Nathan had asked me to come home with him for Thanksgiving that year and I’d said I couldn’t, because it seemed too serious, but later I wondered if I actually wanted that seriousness, or if he did. I couldn’t get a good handle on it one way or the other, but after a few days I said I’d changed my mind and I remember trying to smile a little more than usual, trying to be a nice girl, trying to be one of those girls people take home for Thanksgiving, and he said maybe bring a dessert? so I baked three pies from scratch in the dorm kitchen, overly concerned with the lattice, weaving and re-weaving it until the butter melted and the dough turned loose and gummy. He introduced me to family members as his good friend, Nikky but his aunt called me the girlfriend and his mother just called me Nikky, always saying my name like I’d done something wrong. Nathan and I slept in separate rooms the first night and the same room the second night and the third night we took the bus back to campus and he said, See you around and punched me in the arm and went back to his dorm alone. He didn’t call or leave a message or come over for two weeks, during which my roommate kept saying, Nikky and Nathan, Nikky and Nathan, and I said nothing until I snapped one night – Do you have to be such a fucking college roommate all the time? She barely spoke to me during exam week, then I moved out, dropped out, went back to St. Paul for Christmas and moved to the city alone. The day before I left I called Nathan to tell him we needed to get a beer and he said Sure! as if it was nothing and I hated him and I wore my glasses and a sweatshirt and jeans that didn’t really fit and he told me his thesis was going to be a literary novel and I said, Sure, whatever, but what is this? What are we doing? And he said What? And I said, My roommate keeps saying, Nikky and Nathan, Nikky and Nathan, I said, trying to make him explain who Nikky and Nathan were.

Well, duh, he said, Nikky. . . (pointing at me) and Nathan (then himself.)

Nevermind, I said, and now I know better – no one should trust the feelings that occur at nineteen or twenty. Everyone should just sit very still until they reach the calmer waters of later-young-adulthood, that promised land of lowered expectations. Even so, I still don’t get it – how so many people manage to keep asking the same person the same question everyday – Is this what you want? Am I still what you want – without going insane.

Can I tell you something, he asked that afternoon as Echo rubbed her head against his knuckles. His face looked like a warped, worn-out version of his face ten years before and his apartment seemed like an expansion of his dorm room and our lives and everything in them a drawn-out weird-ass sequel to college, and I said, Sure you can tell me something, but I forgot whatever that something was. I was too tired to be good, to be tender, to care. I wonder if any of those somethings were worth remembering.

And then there was the cat. I was familiar with the cat. We had an understanding.

There had, however, been a series of altercations between Echo and I, years ago, while Nathan and I were in the middle of committing one of those low-grade persistent infidelities: half-clothed and muscling against each other, we knocked over a stack of books near his bed, and Echo appeared, slashed my calf, hissed, bounded across the apartment, and later pounced on my back, howling, and whether she was trying to re-claim her territory or avenge me on behalf of his then girlfriend I do not know, but the next morning as I exited his bedroom, she was sitting in the center of the hallway, staring like a security guard. She made a low hiss, as if saying sssssslut under her breath.

Echo started waiting for me any time I was in the bathroom and when I opened the door she’d be all hisses and flinging claws, forcing me to shut the door which she’d wedge her flexed claws under until Nathan shooed her into his bedroom and shut the door.

A few weeks later she got her head stuck in an empty kleenex box (or maybe Nathan put it on her) and as she spasmed around the apartment Nathan laughed and filmed the struggle with his phone. I said, or maybe just thought, What is wrong with you? as I took the box off Echo’s head, and if a cat is able to express something like surprised gratitude, then this is what was we experienced in our moment of eye contact before she bolted to the kitchen to hide between the refrigerator and the wall. After this she stopped barricading me in the bathroom and stared at me in a way that was notably lacking in hatred.

The first day I let myself into Nathan’s to feed Echo, I could hear a neighbor speaking on the phone, a woman: Do you think they may have that obscure little thing we call internet access at the hotel? . . . So can you figure this out for your own fucking self or do I have to do everything for you? . . . Well – . . . Well – . . . Well if you would let me finish. . . Fucking hell.

I lingered as I unlocked Nathan’s door, trying to discern what the problem was, and as I put food and water out for Echo and felt a fern’s dirt for dryness, I imagined someone in a hotel lobby eavesdropping on the other half of this argument, also trying to discern what the problem was. I sat on the sofa with the vague impulse to read a magazine or take a nap, to make myself falsely at home, but I decided against it and as I left I heard the neighbor say, Well, that’s what I told you, sounding tired and reluctant.

The next day I didn’t hear the woman and the fern had been knocked over, dirt scattered over the rug and hardwood.

We’ve come so far, I said to Echo as she emerged from the bathroom, surprising myself with how quickly I’d turned into one of those people who speak to cats. And now you have to go knocking over a fern. She swayed into the kitchen and ate what I’d put out.

The vacuum was in the second closet I looked in, both of them packed with the kind of mess I remember Nathan living in – broken umbrellas, suitcases, old notebooks, coats wadded in corners, a dozen yellow highlighters and ping pong balls rolling loose. It reminded me of his dorm room and his first apartment and the way this one had been before Analiese. Since then he’d lived in a sort of aesthetic calm: sofa re-upholstered, shoes off at the door, art framed and hanging. He’d even re-painted, correcting the smeared, patchy job he’d done when he’d first gotten this place and his first real job, at 28.

He believed his newly painted walls meant something about him:

I’m in the no-more-bullshit part of my life, he said.

I asked him, Do you think people can really change? but he didn’t answer, just made us cocktails garnished with perfectly coiled lemon rinds, I’m a man who owns a zester, he said, and that he’d done all the dumb shit he needed to do during the part of his life where he did dumb shit, and now he’d basically earned his Dumb Shit Merit Badge and was moving up to Smarter Shit, I guess, improved kitchenware and fidelity.

After the fern was righted and the vacuum thrown back into the closet, I wondered, again, whether or not I should make myself at home, fix a drink maybe, or read a book. I sat on the sofa and thought of how a former therapist had said that with every trauma, we create a clone of ourselves to do the ‘emotional dead-lifting’ and I couldn’t tell if she meant your clones had to lift the ‘emotionally dead’ or if your clone had to hoist a barbell of emotions over its clone head. Either way it sounded like a lot of work was expected of those clones, and I expected that my clones probably lacked the upper-body strength to do that lifting. I imagined all my clones sitting cross-legged on the floor of Nathan’s apartment, waiting on something from me.

I don’t have anything for you, I said to the idea of those clones.

Echo walked in, sat next to the sofa and looked at where my little clone army would be, then went elsewhere. I found a book and started to read it, but I don’t remember what it was because I didn’t really read it, just stared at the first sentence while wondering if I had a clone in me that had something to do with Nathan and maybe that’s where the confusion of what to do in his apartment was coming from, the state of being close to him without actually being close to him, which, I was realizing, was more or less all the last ten years had been and though we called each other ‘one of my oldest friends,’ we weren’t quite friends, just old.

My phone lit up: Nathan Cell.

Are you busy?

Not really. I said. It was nearing dusk.

Because I think I need to talk. I need some advice, he said, but he didn’t really need advice; he just needed to be heard. I paced the apartment while he explained the situation he supposedly needed advice for, how he had de-friended and blocked and un-followed her and how that had prompted her to call him and what he had said and what she had said and so forth, but I stopped listening pretty quickly because I came across a shelf in his bedroom holding a vintage locket and a set of Russian Dolls, both of which seemed to have some kind of sacred significance and nearer to his bed and I recognized a framed lithograph – and it took me a second to figure out why – it was one I’d made in college.

And, you know, I get it. She’s only twenty-five so she’s scared of being so in love. Because what we had was fucking intense, you know? And it’s too much for her, which, you know, I understand. I’m usually the one doing what she’s doing, running –

Yeah, I said, but he kept speaking without breaking stride. I could have been on mute, I realized, and he wouldn’t have known. Then I looked at my phone and I somehow was on mute, so I un-muted myself and said, Yeah, but I knew it didn’t really make a difference. I wondered how long the print had been hanging so close to his bed. The last time I had seen it was in the old apartment and it was unframed and tacked up in a nook between the kitchen and bathroom, somewhere it could be ignored, take up less space. All the designs I did now were on a computer, so there was something that felt overly personal about him having one of my lithographs, a real history of something my hands had done.

How long has my print been hanging in the bedroom, I asked, uncharacteristically interrupting him, a small jolt.

Are you – Are you at my place?

Yeah.

He was quiet for a long second.

I don’t know. A few months, maybe. Analiese helped me rearrange. I think she put it there, and that got him on a rant about how much he changed for her and how happy he was to change for her but she never wanted to compromise anything – she just expected him to come and go whenever she wanted so that’s what he did and he was happy to do it, actually – and he said something about how she was closed to him or close to him and he said it a few times but I couldn’t tell which word was being said. Closed. Close. Closed. . . Either could have made sense, but I don’t know.

When we were younger my attention for him came so easily and I could listen to his endless opinions for hours and I suppose that meant I loved him in a way that only nineteen-year-olds can love, and though I don’t exactly feel that way anymore I do feel some baffling and unexplainable grace, some exhausted affection, though he didn’t deserve it any more than a jar of expired mustard deserves its spot in a refrigerator just by being there for so long without someone having the nerve to throw it away.

And I realized during one of these calls, which became a regular feature of my afternoons and evenings in his apartment, the phone hot on my ear, the battery chiming its impending death, that I almost never told him anything about myself. For instance, my father had died last year, a sudden hemorrhage, and I hadn’t mentioned it. It had happened around the same time I began the celibacy thing (before or after I couldn’t remember) and I had only told my closest friends because I dislike sympathy from strangers, even a post-sneeze bless you. And I guess this means Nathan really was more of a stranger than a ‘good friend,’ or a familiar stranger or a bad friend or some cross of both. Was I just trying to be the Jesus in this relationship, to do what Jesus would do, to offer a grace that wasn’t earned, to care for someone despite all reasons to do the opposite?

Hey listen, I have to go, I said, and he kept talking and I realized I’d hit the mute button again, so I un-muted and repeated myself.

Right, of course, he said. Hey, also, thanks for taking care of Echo. And for listening so much. It’s been really good to talk and reconnect with you.

It’s fine. I hope you – that you feel better. Soon.

Talking to you is helping a lot, he said and I wondered if I really was witnessing him change, if we were going to become sincerely friends, crying shoulders, laughing voices, people you tell about a parent’s death.

Unlocking the door later that week, the arguing woman was back – You’re going to ask me that right now?. . I can’t believe this. . .

I pretended to struggle with the keys, a performance for no one, so I could listen in longer.

You have some fucking nerve. . . When does your flight get in?

I’d been spending increasingly more time at Nathan’s apartment, bringing my laptop over, making coffee, ordering in. Echo would sit in my lap as I worked, as if she had forgotten everything that had ever happened between us. Maybe she had. Maybe I had, too.

Most days during Nathan’s regular call, I’d spend most of the ‘discussion’ doing something else: working on an image, an email, whatever. If I was feeling charitable, I’d paint my nails and mostly listen, maybe even try to find a moment where I could cut into his monologue, dispense some advice that would be almost entirely ignored. At some point I started putting him on speaker and draping myself across the bed, his disembodied voice wafting around like a radio show trying to sound conversational.

I started thinking, abstractly, about inviting Zach over, this man I’d recently been un-celibate with and I thought it would be funny to sleep with someone else in Nathan’s bed, but then I wondered if it said something pathetic about me, because I knew I’d be thinking of Nathan, at least a little, and there would be the issue of doing laundry and I didn’t know where the nearest laundromat was, and then I’d have to tell Nathan I had done his laundry because I’d brought someone back to his apartment, so I decided not to invite Zach over, except that’s not true, I actually did invite him over but he was busy.

You’re cat-sitting for how long?

Two weeks.

I didn’t know you were one of those people who will be so accommodating, Zach said.

I’m not one of those people.

But you don’t even really like cats. And you don’t even really like him. This is the same guy with the Instagram feed that is mostly selfies, right?

That’s the one.

He sounds insufferable.

And I knew Zach was right, that I had often suffered Nathan’s company instead of enjoyed it, but some people are just drawn to other people and the reasons or rules behind who you are drawn to have never been completely clear to me, though I’ve noticed I’ve often been often drawn to people for whom I can set the bar of expectations exceptionally low, people who can never disappoint me because of how little I believe they are capable of. And maybe this is another one of those by-products of having your young heart broken by the idea of Jesus, of losing the belief in a deep and mutual love with a divine entity, and after learning that it was an invention, a long talk to an empty cloud, make believe about a nicer reality than our human reality. I suppose that therapist was right and maybe a person has to make a clone to be able to handle it all and in the meantime a person can only attempt to search out the opposite of Jesus, people who seem barely concerned or even aware of other people’s existence.

But I get it now, Nathan said over the phone, what really makes you happy is loving other people. That’s the only real point in life, and I know that in the past, maybe even with Analiese, I tried to protect myself from that, but I’m over it. I’m not that person anymore.

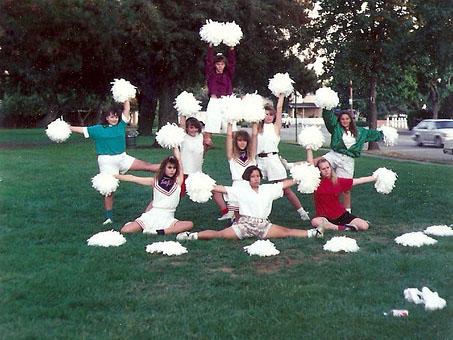

And I asked him, Do you think people can really change? and he was quiet for a little while and I could tell he was really considering it, and in his answer he brought up my religious past, telling me astoundingly accurate summaries of stories I thought he hadn’t even been listening to, like my failure to make it onto the Team Jesus Cheer Squad and the time I’d stolen communion crackers and juice and forced them upon neighborhood dogs and how I tacked up crayon portraits of Jesus in my room the way girls did with cut-outs from Teen Bop and I am still in a state of disbelief about how Nathan’s voice changed in that moment, how tender it was.

The conversation ended but I stayed where I was for a while, nostalgic for the Team Jesus Cheer Squad. A lack of rhythm was what killed the audition, and my stomps and claps hung off the side of the uniform beat all the other girls were in. I was afraid this said something about me (or that the fact that I was afraid that it said something about me was what really said something about me) and I was still lying on Nathan’s bed thinking about this when the fire alarm went off – a high pitched beeping and a computerized man’s voice saying: This is not a test. Please evacuate the building. This is not a test. But I gave myself a minute to not believe that this was a test because I didn’t want to be bothered with getting up, to stop thumbing over the past and start dealing with the present, but I thought I smelled smoke and I knew that all you’re supposed to do in moments like these is just take care of your own bodily self and any nearby children or animals, but that is not exactly what I did. I gathered all my work materials and laptop before even remembering Echo and I tried to find something to carry her in, but I couldn’t find anything, and I tried to pick her up but she was darting around the apartment, rightly disturbed by the voice and deafening pitch and as I chased Echo I could picture the cheerleaders lifting the WHAT – WOULD – JESUS – DO? signs in perfect synchronicity, and it was only then I realized what an unfair question that was because Jesus had, if The Bible is to be believed, supernatural powers, and his options – walking on water, ripping apart dead fish to make more dead fish – are not the options the rest of us have. All I could do was stuff Echo into a reusable shopping bag and take my print off the wall, which is also not what Jesus would have done, but it is what I did because I am not the Son of God – I’m just a person doing what I can.

On the sidewalk with a dozen others I was embarrassed about how much I was carrying, my backpack and purse and this quite large print and a bag of squirming, hissing cat. A few people looked at me and I’m sure silently judged how I was being so materialistic at such a dire moment, and Echo began squirming with increased vigor, so much so that I nearly lost my grip on the print and she leapt from the bag but I was too concerned with safely holding the print to stop Echo from sprinting down the street. I just stood in a dumb shock, and I knew that what I needed to do was leave everything on the sidewalk and go running after Echo, but I was worried about leaving my laptop unattended and I thought the framed print might get scratched or damaged and though I did make a small attempt to run after Echo, I couldn’t exactly see where she had gone. Had I been thinking more clearly or being a better person I would have realized my entire promise to Nathan was that I would keep Echo alive and in my possession, but then I saw the fire trucks coming and I imagined the soon-to-be spectacle of seeing Nathan’s apartment building go up in flames, and that was more engrossing to me than searching for Echo, which seemed hopeless and inconvenient. I thought she might not travel too far, come back when she was hungry, but then the fire trucks actually passed the building and kept going down the street. The alarm in our building stopped and a man with a ring of keys on his hip and a patch on his chest that said CLYDE came out, waving his hands like we had it all wrong.

False alarm, people. Y’all can go back in.

It was only then that I realized that I’d forgotten the keys. I asked Clyde if he could let me back in to 4B but he looked at my sideways.

That’s mister Nathan in 4B and I know his girl and she ain’t you.

Actually, they broke up. I’m just cat-sitting. Except I lost the cat.

How’m I ‘sposed to know they split up, huh? I’m nobody’s momma. I gotta do my job, lady. He didn’t tell me to look out for no cat lady.

I’m not a cat lady – it’s his cat.

But Clyde was walking away and for some reason I held up the print like he was still looking. See? I made this for him. We’re old friends.

And this was, I now realize, the moment I either lost or found something, lost the part of me that was keeping it together and calm, or found the clone that belonged to the small trauma as what happened with Nathan, and either way I knew I had not done the right thing – if there was a right thing – by choosing to protect my things instead of Echo. I looked at the print and became aware of its deep and undeniable hideousness, a still life with the bust of a woman pushed over in it, a pile of grapes beside her. How had this ever been important to anyone?

I don’t care what you made – Clyde said, I’m not letting you in nobody’s apartment, lady.

It was probably for the best, I thought.

Echo? I called a few times, but nothing came back, no cat, no assurance. I had a strong desire to be in Nathan’s apartment again, to celibately drape myself across his bed, to hear him talking through that break-up, to be the shoulder he was crying on without actually crying. But I also wondered if I just wanted all this – to take care of his cat, to water his ferns, to pretend to be at home in his home – out of a being-a-good-friend kindness or as a way to retroactively salve a hurt, a dislocation we had, a thing I could never quite get right, never figure out how to do. I’d always thought our history was just a history, but looking at that awful lithograph and not knowing where Echo was or how to get back inside, I understood that’s the damn thing about the past: it doesn’t go anywhere and it can’t be undone and it’s constantly being made and re-made. The things you do to people are always the things you did to people. My phone binged but it was just junk mail, but then it lit up.

Nathan – Can I tell you something?

Featured photograph © Pascal DURIF; in-text photograph © JLynRobertson