At the end of July 1987, I was in the far north of Peru on a half-deserted beach where years before a young man from Piura and his wife had built several bungalows with the idea of renting them to tourists. Isolated, rustic, squeezed between stretches of sand, rock cliffs and the foamy waves of the Pacific, Punta Sal is one of the most beautiful sites in Peru. It is a place outside of time and history; its flocks of sea birds – gannets, pelicans, gulls, cormorants, ducks and albatrosses called tijeretas – parade in orderly formations from bright dawn to blood-red sunset. The fishermen of this remote corner of the Peruvian coast use simple rafts made in the same way as in pre-Hispanic times: two or three tree trunks tied together with a pole that serves as both oar and rudder. The sight of these rafts had greatly impressed me on my first visit to Punta Sal; they were identical in design and operation to the raft that, according to the Chronicles of the Conquest, Francisco Pizarro and his comrades found not far from here four centuries ago and considered to be the first proof that the imperial myth of gold that had drawn them from Panama to these shores was a reality.

I was in Punta Sal with Patricia and my children for National Holiday Week. We had returned to Peru not long before, from London, where we spend three months every year. I had intended to correct the proofs of my latest book, El hablador, between dips in the ocean, and to practise, from morning to night, the vice of solitude: reading.

I had turned fifty-one in March. All signs were that my life, unsettled from the day I was born, would become calm: a life spent between Lima and London, devoted exclusively to writing, with an occasional university stint in the United States. The previous year, I had dreamed up a ‘five-year plan’ of what I wanted to accomplish before my fifty-fifth birthday and had scribbled it in my memo book.

One. A work for the theatre about a little, old Quixote-like man, who, in the Lima of the fifties, embarks on a crusade to save the city’s colonial-era balconies that are threatened with demolition.

Two. A novel, something between a detective story and a fictional fantasy, about human sacrifices and political crimes in a village in the Andes.

Three. An essay on the gestation of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.

Four. A play about an entrepreneur who, in a suite in the Savoy Hotel in London, meets his best friend from school, someone he thought had died but who has, thanks to hormones and surgery, turned into an attractive woman.

Five. An historical novel inspired by Flora Tristan, the Franco-Peruvian revolutionary, ideologist and feminist, who lived at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

In the same memo book I had also jotted down less urgent projects: to learn that devilishly difficult language German; to live for a time in Berlin; to try, again, to get through books that had defeated me – Finnegans Wake and The Death of Virgil; to go down the Amazon from Pucallpa to Belem do Pará in Brazil; to bring out a revised edition of all my novels. Vague resolutions of a less publishable nature also figured on the list.

On 28 July, at noon, I prepared to listen on a friend’s little portable radio to the annual speech given by the President of the Republic to the Congress on the national holiday. Alan García had been in office for two years and was still very popular. For some his politics – a crude, populist socialism – were like a ticking bomb, waiting to explode. Populist policies had led to catastrophic failures in Salvador Allende’s Chile and Siles Suazo’s Bolivia; why should they succeed in Peru? García’s policy had been to subsidize consumer spending by raising salaries and freezing prices, and it had brought a momentary prosperity: it would last only as long as the country had reserves of foreign currency available to allow for the purchase of imports that were essential for survival (Peru imports a large share of its food and its industrial components).

García’s policies, however, were causing problems. Reserves were now on the point of being depleted, and García was unable to appeal to international financial institutions, having already alienated most of them by his confrontations with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Moreover, his government had taken to printing paper money merely to cover its own debts. Inflation was worsening, and the dollar was being maintained at an artificially low rate (there were in fact any number of rates of exchange for the dollar, depending on the ‘social necessity’ of the product), discouraging exports and encouraging speculation and trading in contraband. García’s policies were enriching only a handful of people, while sinking the rest of the country’s population into poverty that was increasing by the day.

I had only one interview with Alan García while he was president. I had arrived from London and had been met by one of his aides-de-camp whom García had sent to welcome me back. It was the protocol that I then went to the government palace to thank the president for the courtesy. Alan García received me personally, and our meeting lasted for an hour and a half. He showed me a handmade bazooka, put together by Sendero Luminoso – Shining Path, the Maoist guerrilla movement – which had been used to launch a projectile against the palace. He was young and, as a good politician should, knew how to turn on the charm. I had met him only once before, during his election campaign, over dinner at the home of a mutual friend. The impression I left with was of a man driven by his attraction to power and who would do anything to get it. I then appeared on television and said that I wouldn’t be voting for him, but for Luis Bedoya Reyes, the candidate of the Christian Popular Party. And, later still, I would write an open letter to him once he was in power, condemning him for the massacre of rioters in the Lima prisons in June 1986 (hundreds of inmates in three prisons, all members of Sendero Luminoso, rose up in protest and revolt and were summarily killed – even after some had surrendered to the prison authorities). But, despite all this, despite my evident opposition to his policies, García did not bear me any ill will (in fact, at the beginning of his term, he had asked me to accept the ambassadorship to Spain). I said to him, jokingly, that it was a shame that he was determined to be Peru’s Salvador Allende, or Fidel Castro, when he had the chance to be its Felipe González.

In our meeting, García went into great detail describing his objectives for the forthcoming year, illustrating them on a blackboard. One objective he did not mention was the most important. That was the one I would learn about later, listening to García’s annual speech to the Congress on that hot day on the beach of Punta Sal, his voice crackling and broken on the ancient radio: his initiative to nationalize and bring under government control all banks, insurance companies and financial institutions.

I heard this announcement while standing beside an elderly man. He was wearing a bathing suit and a leather glove that hid an artificial hand. ‘Eighteen years ago,’ he said, ‘I read in the papers that General Velasco had taken my country estate away from me. Now, on this little radio, I hear that Alan García has taken my company away from me.’

He rose to his feet and dived into the ocean. Most of the vacationers in Punta Sal that day did not take the news in the same debonair spirit. They were professionals, executives and a few businessmen who were actually associated with the threatened companies. But like the man with the artificial hand, they remembered the dictatorship, twelve years (1968–80) of massive nationalizations. At the beginning of the military regime there were seven nationalized industries; at the end there were over 200. In the name of a socialist participatory democracy, General Juan Velasco Alvarado had nationalized the petroleum, electricity, mining and sugar industries. Peru, when Velasco came to power, was a poor country; he turned it into a poverty-stricken one. Now, as in a recurrent nightmare, Alan García’s ‘democratic socialism’ was about to gobble up banks, insurance companies and financial firms.

At a gloomy meal that evening, the woman at the next table lamented her fate: her husband, one of many Peruvians who had emigrated, had given up a good position in Venezuela to return to Lima – to take over the management of a bank! Would they have to leave Peru again?

‘Once more Peru has taken a step backwards, towards barbarism,’ I remember telling Patricia the next morning. We were going for a run along the beach, escorted by a rectilinear flock of gannets. The nationalizations would increase the poverty, parasitism and bribery of Peruvian life. Sooner or later they would fatally damage the democratic government that Peru was able to retrieve in 1980, after twelve years of military rule.

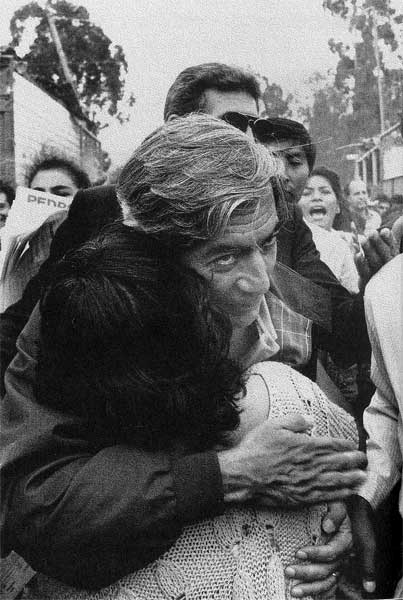

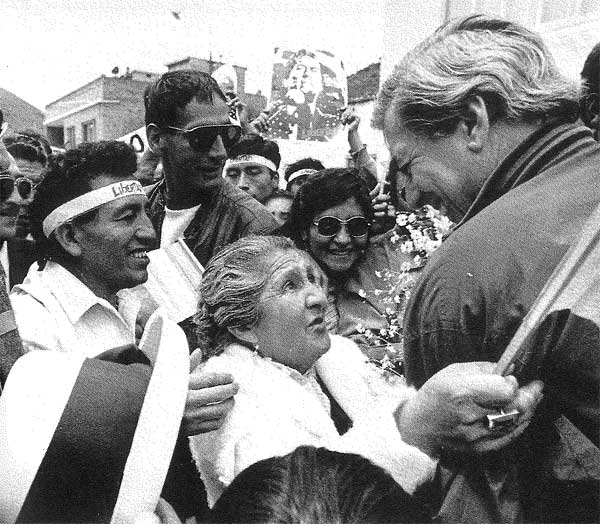

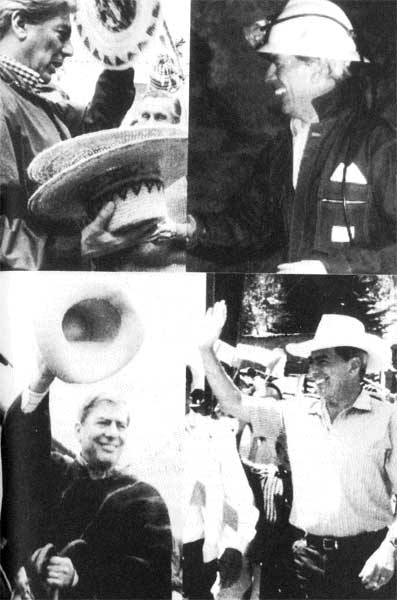

Alan García, on winning the presidential elections in 1985

‘Why the fuss,’ I have often been asked, ‘over a few nationalizations? Mitterand nationalized the banks in France: even though the measure was a failure French democracy was never endangered.’ It is a reasonable point, but it is also one that betrays an ignorance of underdevelopment, which is characterized by its blurring of the roles of the government and the state. In France, Sweden or Britain the public sector has a degree of autonomy in its dealings with those who hold political power; it belongs to the state and its administration, and its personnel and their functions are more or less safe from misuse by the government of the day. In an underdeveloped country, as in a totalitarian one, the government is the state, and those in power administrate it as though it were their own private property, their spoils: the institutions of the public sector provide cushy jobs for protégés and serve to feed people under their patronage. Such institutions turn into bureaucratic swarms paralyzed by the corruption and inefficiency imposed upon them by politics. They never go broke, being monopolies subsidized against competition by the taxpayer’s money (the deficit of running the public sector in Peru in 1988 was 2.5 billion dollars, which equalled foreign currency brought in by exports for the year).

Nobody likes bankers. They symbolize affluence, selfish capitalism, imperialism, all causes of Third World wretchedness and backwardness. Alan García had found, in financiers, the ideal scapegoat for the failure of his programmes: the financial oligarchies had removed their dollars from Peru and made secret loans out of the savings accounts of others to their own companies. With the financial system in the hands of the people, everything would change.

‘The worst of it is,’ I said to Patricia, panting, as we finished our four-kilometre run, ‘this proposal will be supported by 99 per cent of Peruvians.’

I returned to Lima from Punta Sal and wrote an article, ‘Towards a Totalitarian Peru’, that appeared in El Comercio on 2 August. I wanted to put on record my opposition to nationalizing the country’s financial institutions, and the article, outlining my reasons, urged Peruvians to oppose the nationalizations as well, using every legal means possible, if they wanted to see our democracy preserved. I doubted that my article would have much effect; I assumed the nationalization measure would be passed by Congress and supported by the majority of Peruvians.

But I was wrong.

My article appeared on the very day that the employees in the banks and the other threatened services actually took to the streets in Lima, in Arequipa, in Piura. I was astonished, as was everyone else. With four close friend – the architects Luis Miró Quesada, Freddy Cooper and Miguel Cruchaga, and the painter Fernando de Szyszlo – we went a step further and drafted a manifesto and collected a hundred signatures. I read the text on television; it appeared, with my name at the head, in the daily papers the next day, on 3 August, under the banner ‘Opposing the Totalitarian Threat’. The manifesto stated that ‘the concentration of political and economic power in the party in power might well mean the end of freedom of expression and, eventually, of democracy.’

In the next few days my life was changed. There were letters and phone calls and an endless number of supporters of the manifesto visiting my house, bringing piles of signatures they had collected. The names of hundreds of new supporters appeared every day in the media not controlled by the government. People from the provinces stunned me with offers of help. After twenty years of nationalized industry now, in these feverish days of August 1987, significant sectors of Peruvian society seemed to have rejected the formula of government control.

The next week my friends Freddy Cooper and Felipe Thorndike visited me at home. Felipe Thorndike, an entrepreneur and petroleum engineer, had been a victim of General Velasco’s dictatorship, which had expropriated all his holdings, and he had been obliged to go into exile. While abroad, he rebuilt his businesses and, in 1980, returned to Peru determined to work in his native country. Felipe Thorndike and Freddy Cooper had been having meetings with political independents – the majority of Peruvians refuse to be affiliated with any one of the innumerable political parties – and they proposed that we call for a public demonstration at the Plaza San Martín, the big square in Lima. They wanted to call the demonstration a ‘Meeting for Freedom’, and asked me if I would be the main speaker. The idea was to show that not only could members of the left take to the streets to defend state control, but we could also, to defend freedom. I accepted.

That night I had the first of a series of arguments with Patricia that were to go on for a year.

‘If you go on to that platform you’ll end up going into politics, and literature will go to hell, and your family along with it. Don’t you know what it means to go into politics in this country?’

‘I headed the protest against nationalization. I can’t back down now. It’s only one demonstration, one speech. It doesn’t mean I’ll devote my life to politics.’

‘There’ll be more demonstrations and you’ll end up being a candidate. Are you going to leave your books, the quiet life you’re living now, to go into politics in Peru? Don’t you know how they’re going to pay you back?’

‘I’m not going to go into politics or give up literature or be a candidate for office. I’m going to speak at one demonstration, to show that not all Peruvians have been taken in by Alan García.’

‘They’ll burn down our house, they’ll bomb us, they’ll kidnap the children and kill you. Don’t you know what kind of thugs you’re picking as enemies? I’ve noticed that you’ve stopped answering the phone.’

It was true. The anonymous calls had started the day the manifesto was published. They came during the day and at night. To get to sleep we had to disconnect the phone. The voices were different each time. I came to think that it was every García supporter’s idea of fun, once he’d had a drink, to call my house to announce that at any time he and his friends were going to cut off my balls, rape Patricia and my daughter Morgana and cut up my sons’ faces with knives. The calls continued for nearly three years. They became part of the family routine. When, at the time of the elections, they stopped, a sort of vacuum, a nostalgia even, lingered on in the house.

The Plaza San Martín demonstration was set for the next week, 21 August. The days leading up to the demonstration were intense and exhausting, and in retrospect, the most exciting I experienced. So many people had volunteered to help – collecting money, printing pamphlets and placards, preparing pennants, lending their homes for meetings, offering transportation for the demonstrators and driving through the streets in vehicles with loudspeakers. My home was a madhouse, and on the evening of 21 August I hid out for a few hours at the home of Carlos and Maggie, two friends, to prepare the first political speech of my life (Carlos was later kidnapped, by members of the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement and held in captivity for six months in a tiny cellar without ventilation). I made a point of asking shareholders of the threatened companies and members of the two principal opposition parties – Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party – not to become involved so that the demonstration could clearly be seen as an event of principle, a protest by Peruvians who had taken to the streets to defend not personal or political interests but the very values that would be endangered by nationalization.

In the event, not even the most optimistic among us could have predicted what happened that night. The numbers were extraordinary. There were people packed so tightly into the Plaza San Martín, elbow to elbow, that they overflowed into the neighbouring streets. And when I then stepped up to the platform I felt something strange. It was a mix of joy and terror. The spectacle before me was awesome to contemplate. Tens of thousands of people – a hundred thousand at least – were waving flags and singing at the top of their lungs the ‘Hymn to Freedom’, which had been written for the occasion by Augusto Polo Campos, a popular composer. I said that economic freedom was inseparable from political freedom, and this vast crowd fervently applauded. I said that private property and a market economy were the only guarantees of development, and the applause increased. I said that we Peruvians would not allow our democratic system ‘to be Mexicanized’ or let Alan García’s Apra Party become the Trojan Horse of communism. The response was deafening, enveloping, unanimous. Something had changed in Peru.

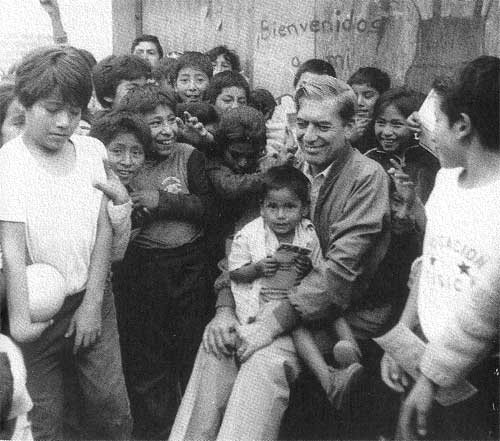

Mario Vegas Llosa at the end of his speech at the Plaza San Martín, 21 August 1987

I had been assigned bodyguards, and there was an incident as I was leaving the Plaza. A private protection agency known as ‘The Israelis’ – its owners came from Israel – was in charge of protecting us. Manuel and Alberto, two ex-marines, had accompanied me to the Plaza and stood at the foot of the speaker’s platform. When I finished, I invited the crowd to go with me to the Palace of Justice to hand over to the members of Congress the signatures against nationalization. During the march, Manuel disappeared, swallowed up by the crowd. But Alberto stuck to me like glue. We were nearly crushed by the demonstrators. Suddenly a black car drove up with its doors open. I was lifted off my feet and put inside. Armed men surrounded me. I assumed that they were ‘The Israelis’. But then I heard Alberto yelling: ‘It’s not them, it’s not them!’ and saw him struggle. He dived into the car just as it was driving off and landed like a dead weight on top of me and the other occupants.

‘Is this a kidnapping?’ I asked, half jokingly, half seriously.

‘Our job is to look after you,’ the bruiser–driver answered. Then he spoke into his hand radio: ‘The Jaguar is safe and we’re going to the moon. Over.’

It was Oscar Balbi of Prosegur, a competitor of ‘The Israelis’. Its president, Juan Jochamowitch, had decided, without anyone’s asking, to protect me and my house.

I had become a politician.

It is said that when Alan García saw the rally on his television that night he smashed the screen in a fit of rage. Because of the rally at the Plaza San Martín the nationalization law, although already passed in Congress, where García’s supporters had an absolute majority, would never be put into effect. It was a death blow to Alan García’s political ambition – he had hopes of remaining in the office of president for an unlimited time – and it opened the doors of Peruvian political life to liberal thought that until then had lacked a way of expressing itself publicly (our modern history has always been dominated by extremes – the ideological populism of conservatives or socialists of various tendencies). It gave the initiative back to the opposition parties, which following their defeat in 1985 had passed into a kind of oblivion.

In the meanwhile, Patricia’s fears were confirmed. Five days later we held another rally in Arequipa, on 26 August. Again thousands attended, but there was also violence. We were assaulted by counter-demonstrators from García’s Apra Party – the famous ‘buffaloes’, the armed hoodlums of the party – and by members of a Maoist faction of the United Left, the Patria Roja (Red Fatherland). They set off explosives and, armed with clubs, stones and stink bombs, launched an attack just as I was beginning to speak in the hope of starting a stampede. The young people in charge of maintaining order on the outer edge of the Plaza resisted, but several were wounded.

‘Do you see? Do you see?’ Patricia said that night. She had been obliged to dive underneath a policeman’s riot shield to escape a shower of bottles. ‘What I was afraid of has already started happening.’ But despite her opposition in principle, she worked morning and night organizing our meetings.

2

At the end of September 1987, all the people involved in organizing the rally were summoned by Freddy Cooper to Fernando de Szyszlo’s studio. There, amid half-finished paintings and masks and pre-Hispanic feather cloaks, we developed the ideas that would be the foundation of a new freedom movement: Libertad. We wanted to create something that was broader and more flexible than a political party, a movement that would unite everyone who had opposed nationalization, particularly the informales, the members of the ‘informal’ economy – the millions of peasants who, unable to participate in the state’s economy, had created their own black market, popular capitalism. We wanted a comprehensive programme of political reform.

We spent hours under the bewitching spell of Szyszlo’s paintings, discussing a plan for governing Peru, and the programme we settled on was one that would revolutionize Peru’s economic and social structures and put an end to privileges, government handouts, protectionism, state control, and create a free society, in which everyone would have access to the market and be able to live under the protection of the law. The programme was characterized by our firm determination to change things, by our resolve to do away with poverty so that every Peruvian could attain a decent life. The programme fills me with pride even now. I contributed only ‘moral support’, the work being done by Lucho Bustamante, Raúl Salazar and dozens of others who devoted countless days and nights to preparing the first rough outline of a new country. It was marvellous to witness. Each time I attended these planning meetings, even the most technical ones – on reforming the mining industry or the practices of the customs office or the port authority or the judicial systems – I felt vindicated: politics had become a task requiring intellect, imagination, idealism, generosity.

In preparing our programme, we attracted engineers, architects, attorneys, physicians, entrepreneurs, economists – people who had not entered politics before and had no wish to be political activists in the future. They were professionals, who loved their profession and wanted to be able to practise it freely. They entered politics reluctantly at the beginning and became active when persuaded that it was only with their co-operation that we could make Peruvian politics into something that was decent and efficient.

Between the first meeting in Szyszlo’s studio and the opening of the Libertad headquarters on 15 March 1988, we worked long and hard, but without a plan, feeling our way. None of us had any experience, and I had less than my friends. I had spent my life in a study, inventing tales in fanatical solitude; it was not the best preparation for organizing a political movement. Miguel Cruchaga, Libertad’s first Secretary General, had likewise lived shut up in his architect’s studio and was most unsociable. He was in no position to make up for my ineffectiveness. He was, however, the first to give up his profession and devote himself full time to the Movement. Others would do the same, managing a living on the small amounts that Libertad could pay them.

My greatest ambition was to attract young people and show them that the real revolution for a country like ours would be one that replaced arbitrariness with the rule of law, and convince them that liberal reform could make Peru a prosperous modern country. It was also one of our goals to retrieve the intellectuals, journalists and politicians who, arguing against socialists and populists and the practices of paternalism and protectionism, had once defended liberalism. To this end we organized our Libertad days – the Jornadas de la Libertad.

These were talks – they lasted from nine in the morning till nine at night – that allowed us to illustrate how nationalization had impoverished the country and how government control had not only destroyed our industries but went against all of our interests, favouring small mafias with a system of quotas and preferential dollar exchange rates. There were talks devoted to explaining the ‘parallel economy’ of the informales and defending its itinerant pedlars, artisans and tradesmen, small-scale business people of modest origins, who in many fields had proved themselves to be more efficient than the state and, sometimes, even large-scale entrepreneurs. A recurrent theme was the necessity of reforming the state and strengthening it by paring away its excesses. There was talk, too, about the four ‘Asian dragons’ – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore (or, separately, Chile) – Third World countries which had market-oriented policies, promoting exports and private enterprise, but whose repressive governments were in flagrant contradiction of every other kind of liberal reform. This was neither acceptable nor necessary. Freedom had to be understood as a principle that was indivisible, politically and economically, and that was, therefore, the raison d’être of the Movement itself: we wanted an electoral mandate from the Peruvian people that would allow us to enshrine this principle in a democratic civilian regime. The point I defended most forcefully was always this – a great liberal reform is possible under democratic rule, provided that a clear majority votes for it, and to achieve it, it is essential to be open and honest, explaining in detail what we want to do and the price we would exact for it. Only in this way would we have the power necessary for ‘the great change’.

We tried to draw a distinction between ‘movement’ and ‘party’, but it was a distinction that turned out to be too subtle for Peruvian political habits. For, despite its name, the Movimiento Libertad was from the start indistinguishable from a party. The majority of our followers assumed it was one, and it was impossible to disabuse them of this notion. Laughable situations arose, symptomatic of a national psychology deeply rooted in the tradition of clientelismo. Every party used the carnet – the individual membership book carried by its members – as a way of giving party members preference when it came to government jobs and favours. We decided that the Movement would not have any carnets. Writing one’s name on a list on a plain sheet of paper was all that would be required to sign up as a member.

It was impossible to get this idea across, particularly in the areas where our followers felt that their status was inferior to that of Alan García’s followers, the Apristas, or the communists or the socialists, who were able to show off impressive-looking carnets full of seals and stamps in bright colours. Our own Executive Committee began to pressure us to issue carnets. Again and again we argued that we wanted to be different from other parties and that we wanted to prevent a Libertad carnet, if we came to power, from being abused in the future. It was no use. I discovered that in certain city districts and towns our committees had begun to give out carnets, each of them loaded with little flags and signatures, and some of them even bearing my photograph! Our arguments of principle had been subordinated to the arguments of the activists: ‘If they aren’t given a carnet, they won’t sign up.’ So at the end of the campaign there was not just one Libertad carnet, but a whole heterogeneous collection of them, invented by various local headquarters to suit themselves.

3

Whenever I’m asked why I was ready to give up my vocation as a writer – what I love most in the world – for the trifling and often contemptible activity that politics had once seemed to me to be, I answer: ‘For a moral reason.’

Circumstances placed me in a position of leadership at a critical moment in the life of my country. It appeared that, supported by a majority of Peruvians, there was an opportunity to accomplish the liberal reforms which I had defended in articles and polemical exchanges since the early 1970s.

Patricia doesn’t see it that way. ‘The moral obligation wasn’t the decisive factor,’ she says. ‘It was the adventure, the illusion of an experience full of excitement and risk. Of writing the great novel in real life.’

This may be the truth. If the presidency of Peru had not been, as I said jokingly to a journalist, ‘the most dangerous job in the world’, I might not have become a candidate. If the decadence, impoverishment, terrorism and constant crises had not made governing the country an almost impossible challenge, it would never have entered my head to take on the task.

But if adventure played its part, so, too, did something else. I don’t want to be grandiloquent, but I shall call it the moral commitment.

Let me try to explain something that is not easy to explain without lapsing into clichés or political rhetoric. I detest nationalism; I see it as a human aberration that has caused much blood to flow; I agree with Dr Johnson that patriotism is ‘the last refuge of a scoundrel’. I have lived a good part of my life abroad and have never felt like a total stranger anywhere. But the relations I have with the country of my birth are more intimate and long-lasting than those I have with any other, including the countries in which I have come to feel completely at home: England, France and Spain. Events in Peru affect me more – make me happier or more angry – than events elsewhere. I cannot justify rationally what I feel: that between me and Peruvians of all races, languages and social strata there is an inviolable bond. Does this stem from my childhood in Bolivia, in an expatriate household, where my mother and grandparents and aunts and uncles considered Peru, the fact of being Peruvian, as the most precious gift ever bestowed on a family?

It is less exact to say that I love my country than that it is continually in my thoughts and a constant mortification. I cannot free myself from it, and it grieves me deeply. It grieves me to see that, for many years now, it has interested the rest of the world only because of the cataclysms that trouble its geography, the record rates of its inflation, the activities of its drug-traders or its terrorist massacres. It is spoken of outside its borders – when spoken of at all – as a horrible caricature of a country that is slowly dying because of the inability of Peruvians to govern themselves with even the minimum of common sense. George Orwell, in his beautiful essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’, says that England is a family with ‘the wrong members in control’. How well that definition applies to Peru! Is it not true that among us are decent people capable of doing, for example, what the Spaniards have done with Spain in the last ten years? But such people have seldom gone into politics, a realm that almost always has been in dishonest and mediocre hands in Peru.

At several periods in my life, before the events of August 1987, I had lost hope in Peru. But hope for what? When I was younger, it was the hope that, in one leap, Peru would become a prosperous, modern and cultivated country. Later, it was then the hope that, before I died, Peru would have begun to eradicate poverty, backwardness, injustice and violence, and that progress, no matter how rapid or how slow, would give every appearance of being irreversible.

Countries today can choose to be prosperous. The most harmful myth of our time, now deeply embedded in the consciousness of the Third World, is that poor countries live in poverty because of a conspiracy of the rich countries which have arranged things to keep them underdeveloped, in order to exploit them. In the past, prosperity depended almost exclusively on geography and power. But the internationalization of life – of markets, technology, capital – today permits any country, if organized on a competitive basis, to achieve rapid growth. In the last two decades, Latin America has chosen to go backwards, by practising, through its dictatorships or bureaucratic populism, a kind of economic nationalism. And Peru has gone even further back than any other Latin American country. The political parties might disagree how much state intervention was desirable, but all of them appeared to accept that state intervention of some kind was necessary and that without it neither progress nor social justice was possible. The modernization of Peru seemed to me to have been put off till pigs had wings.

The Peru of my childhood was always poor: in the last decades, it has become poorer still. A region I have always known well is the departamento of Piura. I lived there as a child and an adolescent, and have travelled in it a fair amount, first with my grandfather and later with my uncle Lucho, who had a smallholding in the Chira Valley where he grew cotton. I returned recently and couldn’t believe my eyes. The little towns in the provinces of Sullana and Paita, or those in the mountains and the desert, seemed to have died a living death: they languish in hopeless apathy. It is true, in my memory, that the dwellings were always crude, made of clay and wild cane, that people went barefoot, that the roads were bad and that there were no medical dispensaries, schools, water or electricity. But in these poor small towns of my childhood, there had been at least a powerful vitality – a light-heartedness, energy, hope – that now had died out entirely.

Piura illustrates the nineteenth-century naturalist Antonio Raimondi’s description of Peru as ‘a beggar sitting on a bench made of gold’. It shows how a country chooses underdevelopment. Off the coast of Piura is a wealth of fish; offshore, there is oil; in the desert there are immense phosphate mines that are yet to be worked; the soil, having once produced cotton, rice and fruit on its landed estates, is one of the most fertile in Peru. Why should an area with these resources die of starvation?

General Velasco confiscated the large landed estates where, in fact, the workers received a very small percentage of the profits, and turned them into co-operatives, ‘social properties’, where the peasants were meant eventually to replace the former owners. They did not. The owners were replaced by directors who ended up exploiting the peasants as much as, if not more than, their predecessors. In the past, however, the owners, knowing how to work the land, also knew to re-invest profits and replace worn-out machinery; the new heads of the co-operatives did not, with the result that there were no profits to share (in the sixties, Peru’s income per capita from animal husbandry was the second highest in Latin America; in 1990, it was the second lowest; only Haiti’s was worse).

Commercial fishing is another example. In the fifties, thanks to the vision and energy of a group of entrepreneurs, a great industry emerged on the Peruvian coast: the manufacture of fish meal. In a few years Peru became the number one producer in the world. Dozens of factories were built. Thousands of jobs were created, and the little port of Chimbote was transformed into a large commercial and industrial centre, developing commercial fishing to such an extent that by the 1970s Peru had a larger fishing industry than Japan.

Velasco’s military dictatorship nationalized the fisheries and made them into a gigantic conglomerate – Pesca Perú – which he put in the hands of a bureaucracy. The industry was ruined. By 1987, fish-meal factories had closed in La Libertad, Piura, Chimbote, Lima, Ica and Arequipa. And while boats of the conglomerate rotted in the harbours for lack of spare parts, the conglomerate itself received huge state subsidies, further impoverishing the nation. It has now been closed. When I heard that the inhabitants of Atico, a little town on the coast of Arequipa, had gathered, with their mayor at the head, to plead for the ‘privatization’ of the fish-meal factory, I flew there to show the townspeople that my sympathies lay with them. I remembered that the harbour had been bustling with fishing smacks and small sea-going boats and that the streets had been jammed with camareros – refrigerator trucks – that crossed the vast desert for the anchovies and other fish needed by the factories in Chimbote. I was taken aback by what I found when I arrived; the coast was overcome by inertia.

Meanwhile the deposits of oil remain underground. The wells were once run by the Belco Oil Company, but the company became involved in litigation with the government. And so, during his first year in office, Alan García simply nationalized the oil company: end of dispute. Having been an exporter of petroleum, Peru now needs to import it.

There are reasons why no one extends credits to Peru, why no one invests.

On 3 June 1990, I had a public debate with my adversary. Alberto Fujimori gibed: ‘It seems that you would like to make Peru a Switzerland, Doctor Vargas Llosa?’ I admitted that the idea did not displease me. Fujimori smiled; he had won a point. Wanting to see Peru made into ‘a Switzerland’ came to be, for a considerable number of my compatriots, a grotesque goal. But on that night of 21 August 1987, standing before the deliriously enthusiastic crowd in the Plaza San Martín, I had the impression – the certainty – that there were hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Peruvians who had suddenly decided to do the impossible and make Peru ‘a Switzerland’ some day, a country without the poor or the unemployed or the illiterate, a country of cultured, prosperous and free people, and that they had decided to bring about this change without bullets, with nothing but votes and laws, within the framework of democracy.

4

All over Peru people began to talk of the alliance: the democratic forces opposed to both Apra, García’s once-revolutionary party, and the United Left, the coalition of communists and socialists, who had won the 1985 elections. In Lima members of the two opposition parties, Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party, were starting to join our movement of independents. The same thing happened in Piura and Arequipa.

I visited, separately, the leaders of both parties: Fernando Belaúnde Terry of Popular Action, who had himself twice been elected president, once having been deposed by a military dictatorship and once being the successor to it (when, despite popular support, he did little to remedy the disasters of the previous regime); and Luis Bedoya Reyes of the Christian Popular Party, the candidate I had supported against García in the elections of 1985. Both Belaúnde and Bedoya expressed support for the idea of working together, and after a series of lengthy and sometimes tense meetings, we agreed to set up a tripartite commission that would co-ordinate an alliance between us. Three delegates would represent Popular Action; three, the Christian Popular Party; and three other ‘independents’ would represent the Libertad movement of which I was the recognized leader.

Many have criticized me for forming an alliance with two traditional parties which had already been in power (for a good part of Belaúnde’s two terms as president, Bedoya had been his ally). This alliance, my critics maintain, compromised the freshness of my candidacy and made it appear to be an instrument of the old bosses of the Peruvian right.

‘How could Peruvians have believed in the “great change” that you offered,’ I was asked, ‘if you linked arms with those who governed the country between 1980 and 1985, without changing a thing that had been going badly? When you joined up with Belaúnde and Bedoya you committed suicide.’

I was aware of the risks, but I decided that they were outweighed by the benefits of an alliance. Many reforms were needed in Peru, and, to see them through, a broad popular base was required. Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party had impeccable democratic credentials and could influence significant sectors of the populace. To present ourselves to voters as separate parties would split support between the centre and right and make either United Left or Apra the winner. The negative image of ‘old pols’ could be effaced with our new programme, reforms that had nothing to do with the populism of Popular Action or the conservatism of the Christian Popular Party but that would be associated with a radical liberalism never before put forward in Peru. Perhaps, most important, Libertad consisted mainly of members with no political experience – there was no party apparatus – and we needed help from the established parties merely to compete with both Apra (which in addition to its own organization could also depend on the machinery of the state in its campaign) and a left that had been battle-hardened in a number of elections.

5

Over a three-year period I met with Belaúnde and Bedoya several times a month. At the beginning we met in different places to avoid reporters; later we met principally at my house, in the morning, around ten o’clock. Bedoya would arrive late, which irritated Belaúnde, who was always punctual and eager for the meetings to end so he could go off to the Club Regatas to swim and play badminton (he sometimes came with his training shoes and racket).

It is hard to imagine that there could be two politicians so different from each other. Bedoya came from humble origins – his family was lower middle class – and he had worked long and hard to be able to carve out a career as an attorney. He was not, however, a good speaker and, worse, was given to making impetuous statements in public. His political career had had a brief apogee – he was Lima’s magnificent mayor during Belaúnde’s first term – but afterwards he could do nothing to shake off the labels of ‘reactionary’, ‘defender of the oligarchy’ or ‘man of the extreme right’ that the left pinned on him. He ran for president in 1980 (against Belaúnde among others) and again in 1985 (against García) and was defeated both times. Peruvians were never going to allow him to head their government.

Bedoya’s long-winded, courtroom-style soliloquies used to infuriate Belaúnde, uninterested as he was in ideologies and doctrines and constitutionally allergic to anything abstract (the ideology of his Popular Action party consisted of an elementary imitation of Roosevelt’s New Deal – a great many public works projects – nationalistic slogans such as ‘The conquest of Peru by Peruvians’ and romantic allusions to the empire of the Incas and the pre-Hispanic people of the Andes). But of the two, Bedoya proved to be the more flexible: he was the one ready to make concessions for the sake of the alliance that we were trying to forge between the three of us, and once we had arrived at an agreement, he could be counted on to fulfil it to the letter. Belaúnde always conveyed the sense that the alliance was there to serve his Popular Action, and Bedoya and I were merely two bit players. Beneath his elegant manners, there was vanity and stubbornness and a touch of the caudillo accustomed to doing and undoing whatever he pleased without anybody in his party daring to contradict him. Belaúnde, born to an aristocratic family (although not a wealthy one), had reached the winter of his life heaped with honours: he had been president twice and was seen to be an upright, democratic statesman, an image that not even his most bitter adversary could deny him. He was a good public speaker with a splendid nineteenth-century rhetorical style, a man of melodramatic gestures – fighting a duel, for instance. When he had suddenly emerged as a public figure in the last years of General Odría’s dictatorship (1948–56), he was seen as a reformer, determined to make social changes and modernize Peru. When he became president in 1963, he stirred up enormous hope. But his administration accomplished little and the military coup by General Velasco in 1968 sent Belaúnde into exile in the United States, where he lived during the dictatorship, very modestly, teaching. Perhaps his one strength was being able to survive until the next election because in every other respect – and above all in economic policy – he was a failure. During his second term as president (1980–85), the national debt increased dangerously, corruption contaminated his administration and inflation raged unchecked. Belaúnde also failed to confront terrorism: at the time it was only beginning and could have been stopped.

I voted for Belaúnde every time he ran, although I was aware of his shortcomings. I defended him during his second term. After twelve years of dictatorship the reconstruction of democracy was the first priority, and I felt it could be best attained if Popular Action was returned to power. Belaúnde, a man of decency, has two qualities that are not often found in a Peruvian politician: a genuine belief in democracy and absolute honesty (when he left the government palace he was poorer than when he entered it); but I refused, with one exception, all the posts he offered me: embassies in London and in Washington, the ministries of education and foreign relations and, finally, the office of prime minister. The exception was my unpaid, month-long appointment to the commission investigating the killing of eight journalists in Uchuraccay, a remote region of the Andes, an appointment for which I was mercilessly attacked and slandered for months by the press and which gave Patricia and me nightmares.1

It was during Belaúnde’s second term that he summoned me unexpectedly to the government palace one night. He is a reserved man who never reveals his intimate thoughts. But on this occasion – over the next few months we would have another two or three meetings – he spoke explicitly and with emotion, allowing me to glimpse the subjects that were tormenting him. He had appointed financial experts to manage the country’s economy, had given them licence to do whatever they wanted, and he was deeply distressed by the result. History would not remember the advisors; it would remember him. Moreover, some of their advisors were insisting on being paid in dollars at a time when everyone else was being asked to make sacrifices. There was melancholy and bitterness in his voice and in his silences.

What would happen to Peru after the 1985 election? he wanted to know. He could see that his own party wouldn’t win, nor would the Christian Popular Party, since Bedoya lacked the power to draw people at the polls. This would mean the triumph of Apra, with Alan García as president. The consequences were frightful. ‘Peru,’ Belaúnde said that night, ‘has no idea what that young man may be capable of if he comes to power.’ He must be stopped and could be stopped, Belaúnde said, if I were the candidate of Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party. He thought I would attract the independent vote. He countered my protestations that I was no good at politics (as time would confirm) with flattery and kindness – I would even say affection, if this word were not so much at odds with Belaúnde’s sober, unemotional personality.

Bedoya once described Belaúnde as ‘a master at taking the syringe out of his backside’, and in fact it was impossible to pin him down or discuss any subject that wasn’t to his liking. He always managed to slip off at a tangent, telling anecdotes about his travel – he had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the country’s geography, having been all over Peru on foot, on horseback, in a canoe – or about his two terms in office, without giving anyone the chance to interrupt him, and then would look suddenly at his watch, get to his feet – ‘Well, just look how late it’s got’ – bid us goodbye and disappear.

It is not surprising that in the three years I never once talked with Belaúnde and Bedoya about the Alliance’s policy for running the country. We knew that the parties in the Alliance had different plans, but we preferred to leave the problem of reconciling them for a later time. We talked instead about the political gossip of the moment or about what Alan García’s next machination might be – what ambush, intrigue or infamy he might be preparing. Sometimes we did succeed in discussing – if we could manage to keep Belaúnde from wandering off – the question of whether the Alliance should present joint candidates in the municipal elections. The elections were set for November 1989, five months before the presidential election. Bedoya and I both felt that we should present joint candidates. Belaúnde disagreed. The subject would present us with our most serious crisis and came close to bringing about the end of the Alliance. It was in itself an education in politics.

On 29 October 1988, the three of us settled on a constitution – it took us a full year to draw it up – and it was agreed that we would present it in a ceremony in the Plaza de Armas in Trujillo. The presentation, however, served only to reveal the quarrels and rivalries between us. Contrary to what had been agreed on for public appearances – that everyone deliver the same cheers and slogans to show the ‘fraternal spirit’ that reigned in the Alliance – supporters of each of the three parties hailed only its own leader and shouted only its own rallying cries, to show who was stronger.

At one rally there was an argument over the order of speakers. Bedoya insisted that as the leader and future presidential candidate, I ought to have top billing and deliver the closing address. Belaúnde objected on the grounds of his age and his status as ex-president. Belaúnde prevailed: I spoke first, then Bedoya, and Belaúnde ended the meeting. Matters of protocol took up much of our time and gave rise to suspicions and jealousies.

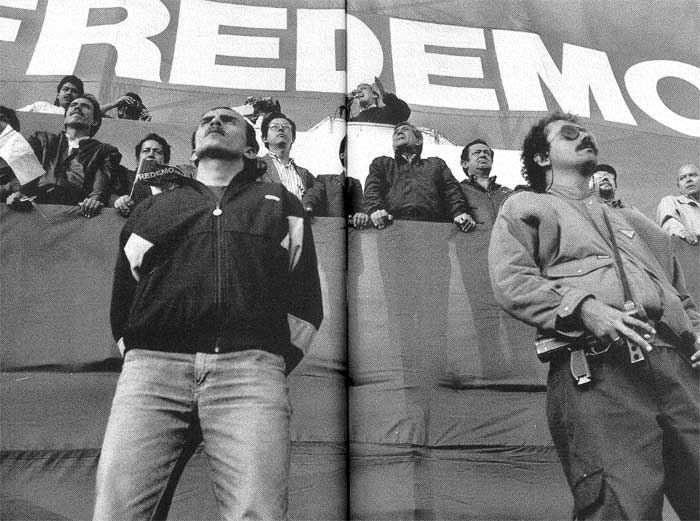

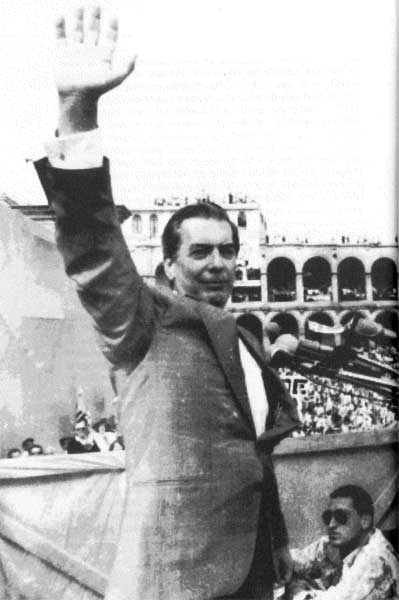

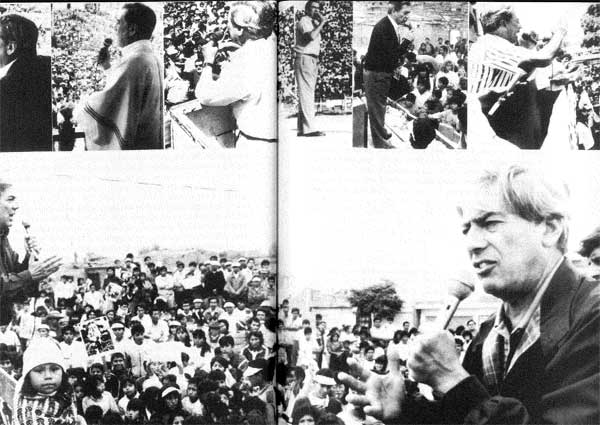

Left to right: Luis Bedoya, Fernando Belaúnde and Mario Vargas Llosa on the day the Alliance was announced in April 1989

The realities of politics became particularly evident when finally we confronted the municipal elections. They would serve as the preliminary round of the presidential electoral contest and would be a measure of the relative strength of the contending parties. Before we had even properly discussed the subject, Belaúnde announced that Popular Action would put up its own candidates, since the Alliance existed only for the presidential election.

Bedoya agreed with me that if each of the three political forces went its separate way in these preliminary elections it would create an image of division and antagonism that would drastically reduce the chances of the Alliance taking root. When we were by ourselves, Belaúnde told me that the populist rank and file of his party wouldn’t stand for the idea of sharing the candidates with the Christian Popular Party, which had little influence outside of Lima, and that he could not risk having rebellions within his party.

Since the whole problem was about a bid for the most power, I said that the Libertad movement would be prepared to abandon the idea of putting up any candidate for mayor or alderman or any other municipal office anywhere in Peru, so that Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party could share the candidacies between them. I thought that this gesture would make it easier for us to come to an agreement. But not even then would Belaúnde agree. The matter attracted the attention of the news media, which, biased in favour of the government, did their utmost to show the internal weakness and tension that, according to them, were eating away at our alliance.

Finally, after innumerable arguments – some so heated they seemed on the verge of becoming violent – Belaúnde gave in and accepted my proposal. Another fight began between Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party, this time over which of the two would put up the candidate for each of the municipalities. They never reached an agreement; neither party seemed prepared to make further concessions. In the meanwhile, members of the Libertad movement objected to the agreement I had made with Belaúnde and Bedoya – not to put up municipal candidates ourselves – and there were a number of defections.

Belaúnde had placed the greatest obstacles in the way of an agreement concerning the municipal elections, but it was Bedoya who brought on the crisis. On the night of 19 June 1989, Bedoya appeared on television and denied what I had just announced at a press conference: that Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party had reached agreement over the municipal candidacies in Lima and Callao, the two most hotly disputed elections. I watched Bedoya’s declaration just after getting into bed. I got up, went to my desk and spent the rest of the night reflecting on my difficult position and the disunity of the Alliance.

frente democratico (the alliance): Libertad

(Mario Vargas Llosa), Popular Action (Fernando Belaúnde), Christian Popular Party (Luis Bedoya). Presidential candidate in 1990: Mario Vargas Llosa.

change ’90: Presidential candidate in 1990: Alberto Fujimori.

apra (american popular revolutionary alliance) Leader: Alan García (President of Peru 1985–90). Presidential candidate in 1990: Luis Alva Castro.

united left: Presidential candidate in 1990: Henry Pease.

socialist left: Presidential candidate in 1990: Alfonso Barrantes.

Was it worthwhile to go on with the commitment I had made? Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party would continue squabbling to see who was going to head the electoral lists and how many aldermen and mayors each party would get until the Alliance had lost all its prestige. Was it in this spirit that we would achieve the great peaceful transformation of Peru? Was it possible with such an attitude to turn Peru into a ‘country of owners and entrepreneurs’, rid it of mercantilist practices, do away with the mentality of the handout and foster popular capitalism? If we were elected, would we do exactly as the Apristas had done – divide up the administration into small units and create more public posts for party loyalists?

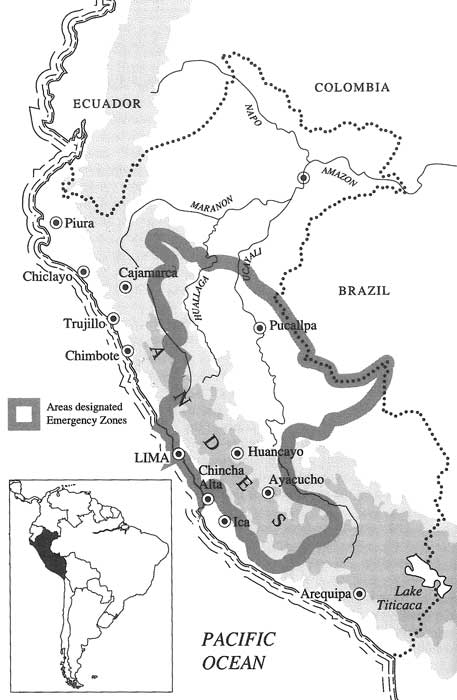

I had been blind to what was going on. Had Belaúnde and Bedoya forgotten Peru? Whole regions – the Huallaga area, in the jungle, and almost all of the central Andes – were under the effective control of Sendero Luminoso and the Túpac Amaru Movement. Companies were working at a half and sometimes a third of their proven capacity. Tax revenues had fallen off, and the country was suffering from a general collapse of public services. Every night the television screens showed heartbreaking scenes of hospitals without medicines or beds, schools without desks and blackboards and sometimes without roofs or walls, districts without water or light, streets strewn with refuse, production workers and office clerks on strike to protest the dizzying fall in the standard of living. And the Alliance, born amid hopes of remedying this catastrophe, was paralyzed for weeks, months, over which party would propose its list in the municipalities!

Dawn came and I drew up a letter addressed to Belaúnde and Bedoya, informing them that, in view of their inability to reach an agreement, I was giving up my candidacy for president. I woke Patricia up to read her the text, and we made plans to go abroad to avoid the expected reaction. I had been invited to receive a literary prize in Italy, and the next day we bought our tickets, in secret, for twenty-four hours later. I sent the letter, via Alvaro, my elder son, to Belaúnde and Bedoya, after informing the executive committee of Libertad of my decision. My friends wore sad faces on receiving the news, but none of them attempted to dissuade me. They too were tired of the absurd way in which the Alliance had got bogged down.

I gave instructions to the security guards not to allow anyone to enter the house, and we unplugged the telephone. The news reached the media and had the effect of an explosive. All the channels began their nightly news programme with the story. Reporters surrounded our house, and supplicants arrived from all the political camps of the Alliance. But I received no one and did not come out of the house when, later in the evening, hundreds of libertarians demonstrated outside.

Early in the morning of 22 June the security guards took us to the airport and got us aboard the Air France flight. We avoided another demonstration of libertarians, whom I spied in the distance from the window of the plane. When we arrived in Italy, two journalists were waiting for me. Heaven only knows how they had discovered I was coming. One was Juan Cruz from El País in Madrid, the other was Paul Yule of the BBC, who was making a documentary on my candidacy: he was the first to express the view that my withdrawal had simply been a tactic to force my intractable allies to give in.

In fact most people ultimately viewed my withdrawal as proof that I wasn’t such a bad politician after all. The truth is that it was not planned, but was a genuine expression of my loathing for the political manoeuvring in which I found myself submerged. This is disputed by Patricia, who lets me get away with nothing. I did not, she says, announce that my resignation was irrevocable, and she thinks that in some secret place I harboured the illusion, the desire, that my letter would settle the differences among the allies.

It certainly appeared to have that effect. On the day I left, the independent media began to criticize Bedoya and Belaúnde severely. The number of people who were prepared to vote for me rose markedly. The opinion polls had always shown me to be the leading candidate, but I never had support greater than 35 per cent. After my withdrawal that figure rose to 50 per cent, the highest I attained at any point in the campaign. In my absence Libertad enrolled thousands of new members, ran out of membership cards and had to print new ones. Local headquarters were filled to overflowing, day and night, by supporters who wanted Libertad to break with Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party and go before the voters by itself. I learned later that 4,980 letters had arrived from all over Peru, congratulating me for having broken with the two parties, with Popular Action in particular.

Mark Malloch Brown managed to reach me to congratulate me as well. He was a member of the public relations firm Sawyer Miller – we had only recently hired their services – and he had already advised me before to break with the allies. He wanted me to present myself as an independent candidate coming to ‘save’ Peru from the state in which the ‘politicians’ had plunged it. His surveys, he said, had shown that there was, in the heart of the country, a profound disillusionment with, if not outright contempt for, political parties, particularly those that had already enjoyed power.

He was, therefore, delighted to learn of my resignation and was not in the least surprised by the instant shift of public opinion in my favour. He thought I had planned it all.

Mark once said to me that I was the worst candidate he had ever worked with.

Patricia and I took refuge in the south of Spain, still fleeing from the press. I had decided to stick with my withdrawal. I had a long-standing offer to spend a year in Berlin, and I proposed to Patricia that we go there.

The news then reached me that Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party had reached agreement on all points of contention between them and had drawn up joint lists of candidates for all municipal contests. Their differences had vanished, as if by magic. They were waiting for me to return to Peru, to rejoin the Alliance and resume my campaign.

My first reaction was to say to myself: ‘I’m not coming. I’m no good at that sort of thing. I don’t know how to carry it off, and what’s more, I don’t like it. These months have given me more than enough time to realize that. I’ll stick to my books and my papers, which I never should have left.’ My wife and I had another argument, one of the longest and loudest of our married life. She, who had come close to threatening to divorce me if I became a candidate, now urged me to go back to Peru, marshalling moral and patriotic arguments. Since Belaúnde and Bedoya had backed down, there was no alternative. That had been the reason for my resignation, hadn’t it? Well then, it no longer existed. Too many good, unselfish, decent people back in Peru were working day and night for the Alliance. They had believed my speeches and exhortations. Was I going to let them down, now that Popular Action and the Christian Popular Party were beginning to behave decently? The sawtooth mountain ranges of the lovely Andalusian town of Mijas echoed to her admonitions: ‘We’ve taken on a responsibility. We have to go back.’

That is what we did. I reconfirmed my candidacy for the president of the Republic of Peru.

6

One night, a man from Los Jazmines, the slum adjoining the airport of Pucallpa, saw two men emerging out of a patch of underbrush who then proceeded towards the end of the runway. They stopped – one of two unscheduled Aero-Perú flights had just arrived from Lima – and then turned back. They were carrying something. The man from Los Jazmines alerted other people from the slum, who formed a patrol armed with clubs and machetes, and went to the runway to check on the two men. They found, surrounded and apprehended them, but as they were about to take them to the police station, the two men drew revolvers and fired point-blank. A man named Sergio Pasavi was shot six times in the stomach – his intestines were perforated. A man named José Vásquez was shot in the leg, his thigh bone shattered. Humberto Jacobo, a barber, was shot in the shoulder, his collarbone fractured. Víctor Ravello Cruz was shot in the groin. The two strangers then got away but they left a bomb behind, a two-kilo ‘Russian cheese’, containing dynamite, aluminium, nails, buckshot, bits of metal and a short wick. They were intending to throw the bomb at the second unscheduled flight from Lima, a small Fawcett twin-engine plane, that, having left at the same time as the Aero-Perú flight, was two hours late. I was on that plane.

Shortly after the municipal elections on 26 November 1989, a naval officer, dressed in civilian clothes and obviously taking unusual precautions, arrived at my house. A meeting between us had been arranged in person by a mutual friend, Jorge Salmón, since my telephones had been bugged. The officer arrived in a car with protective glass windows. He had come to tell me that the Office of Naval Intelligence, to which he belonged, had learned of a secret meeting held in the National Museum, attended by President Alan García; his minister of the interior, Augustín Mantilla, who was widely held to be the organizer of the counterterrorist gangs; Carlos Roca, a congressman; and Kitazona, the head of security, García’s ‘elite’ paratroopers. At this meeting it had been decided to eliminate me, along with my son and two other political colleagues. The assassinations would take place in a way that would suggest that it was the work of Sendero Luminoso.

The officer presented me with a report that the intelligence service had forwarded to the Chief Commandant of the Navy. I asked him how seriously the service regarded this report. He shrugged and said that if the river made a noise it was carrying stones, as the saying had it. My son Alvaro passed the news to Jaime Bayle, a young television reporter, who made it public. The Navy denied the report’s existence.

Less than a month later, Acción Solidaria, a group sponsored by Libertad and headed by Patricia, organized a rally in the Alianza Lima Stadium, with the participation of film, radio and television celebrities. It was attended by 35,000 people. Shortly after the rally began, it was announced over the radio that a bomb had been found in my house and that the bomb squad of the Civil Guard had managed to defuse it. My mother and in-laws, the secretaries and the assistants, were forced to leave the house. That the bomb was discovered as the rally was beginning suggested that the perpetrators had intended to spoil the celebration and make us leave. Patricia and my children and I decided to remain until the rally ended. The suspicion that it was not a real bomb attempt but a ploy was confirmed that night, when the bomb squad of the Civil Guard assured us that the ‘device’ – discovered by the watchman of a tourism school next door – wasn’t filled with dynamite but with sand.

There were always meant to be attempts on my life and the lives of my family. Some were so absurd that they made us laugh. Others were obvious fabrications of the informants who used them as pretexts to get through to me. Still others, like the anonymous telephone calls, appeared to be psychological manoeuvres by Alan García’s followers, intended to demoralize us. And then there were the reports by ‘people of good will’, who in reality knew nothing precise, but suspected that I might be killed and came to talk to me about vague ambushes and mysterious attempts on my life because that was their way of begging me to take care. In the final stage of the campaign this reached such proportions that it became necessary to put a stop to it. I asked Patricia and my secretaries not to grant appointments to anyone who had asked to discuss ‘a serious and secret subject having to do with the Doctor’s security’ (in Peru I’m called ‘Doctor’).

Was I afraid? Apprehensive, yes, many times, but more of objects that I could see being hurled at me than of bullets or bombs. One tense night in Casma, as I was going up to the speakers’ platform, Aprista counter-demonstrators bombarded us with stones and eggs. Patricia was hit on the forehead with an egg. In Lima one morning, the good head (in all senses) of my friend Enrique Ghersi, who was walking beside me, stopped the stone that had been hurled at me (I got away with being doused in smelly red paint).

My life had changed. It ceased to be private. Until I left Peru in June 1990, after the second round of voting for the presidency, I lost the privacy that I had always guarded jealously.

At all hours people were at my house, holding meetings, conducting interviews, organizing demonstrations, talking with me, Patricia or my son Alvaro (who would eventually become our press spokesman). Reception rooms, hallways, stairways were occupied by men and women whom I had never met. I often didn’t know what they were doing there. I was reminded of Carlos Germán Belli’s poem: ‘This is not your house’.

A room was built next to my study, where I always wrote by hand, to hold new machinery: computers, faxes, photocopy machines, intercoms, typewriters, new telephone lines, filing cabinets. This new office, only a few steps from our bedroom, operated from early in the morning till late at night, except during the weeks immediately preceding the election, when it operated until dawn. I came to feel that I was living on permanent exhibition, that every intimate detail of my life had become public information.

For a time we had two bodyguards inside the house. Armed men with pistols appeared wherever I turned and terrified my mother and mother-in-law, until finally Patricia ordered them to stay outside the house.

The campaign forced me to give up my favourite afternoon activity: wandering through different neighbourhoods, exploring the streets, slipping into matinées at local movie houses that creak with old people and where the fleas make viewing impossible, climbing on to jitneys and public buses with no fixed destination, learning little by little the secrets of the labyrinth that is Lima. In recent years I had become well known in Peru – more for my television programme than for my books – and it was no longer easy for me to stroll about anonymously. But now it was impossible. I could not go anywhere without being surrounded by people and applauded or booed. Being followed by reporters and surrounded by bodyguards – after the first two bodyguards, there were then four, then in the last months fifteen or so – made for a spectacle that looked like something between a clown’s act and a provocative display of aggression. My schedule left me with little time for things unrelated to politics, but even in my rare free moments it was unthinkable for me to enter a bookshop. My public appearances gave rise to demonstrations, as happened at a recital by Alicia Maguiña in the Teatro Municipal, where the audience, on seeing me come in with Patricia, divided into supporters who applauded and opponents who stamped on the floor and jeered. In order to see José Sanchis Sinisterra’s play ¡Ay, Carmela! without incident, I sat by myself, in the balcony of the Open Air Theatre. I mention these performances because they were the only ones I attended during my campaign. As for movies, which I am as fond of as I am of books and the theatre, I went two or three times at most, but I was always forced to attend them in the manner of someone who had sneaked in (entering after the film began and leaving before it ended). The last time I attended the cinema – the Cine San Antonio in the Miraflores district of Lima – I was forced to leave early: halfway through, one of my colleagues found my seat and told me that one of our headquarters had been bombed and that the watchman had been shot. I went to soccer games two or three times and to a volleyball match, as well as to bullfights, but these appearances had been decided on by the campaign directors of the Alliance, for the purpose of ‘mingling with the crowd’.

There were a few diversions that Patricia and I could allow ourselves. One was going to the houses of friends for dinner. Another was eating in a restaurant, although when we were there we felt like performers in a stage show. I often thought, my spine tingling: ‘I’ve lost my freedom.’ If I were president, my life would continue like this for five more years. And I remember the odd feeling – it was happiness – when, on 14 June 1990, I landed in Paris – it was all over at last – and before unpacking I went for a walk down the Boulevard Saint-Germain. I was a free man once again. I was an anonymous passer-by. I was without escorts or police bodyguards. I was not recognized. And then, all of a sudden, as if by spontaneous generation, there appeared in front of me, blocking my way, the ubiquitous, omniscient Juan Cruz, of El País, to whom I found it impossible to deny an interview.

When my political life began, I resolved: ‘I’m not going to stop reading and writing for at least a few hours every day. Not even if I become president.’ It wasn’t a selfish decision. It was dictated by my conviction that what I wanted to do, as a candidate and as head of state, would be done better – with greater will, enthusiasm and imagination – if I kept intact a private, personal space of ideas, reflections, dreams and intellectual work, walled in to keep out politics and current events.

I fulfilled only part of my promise: I read, although not as much as I had hoped. Writing was impossible. It wasn’t only for lack of time. Although I woke very early, and entered my study before the secretaries arrived, I never got used to the idea that I was actually alone. It was as if some mysterious muse, unknown to me until then, had grown resentful at the lack of solitude and had left my study for good. It was impossible for me to concentrate, to give myself over to the play of imagination, to attain that state of breaking away completely from and suspending everything around me, which is what is so marvellous about writing fiction and, in my case, essential to be able to do it. Preoccupations far removed from pure literature kept interfering, and there was no way of banishing them, of escaping from the march of events. In the three years of my campaign I wrote only a series of forewords for a collection of modern novels, and some speeches, articles and little essays on politics.

With so little time, I became very exacting in my reading. I stayed on safe ground: I couldn’t offer myself the luxury of reading as widely or anarchically as had been my habit. I chose books that I knew would hypnotize me. I re-read Malraux’s La condition humaine, Melville’s Moby-Dick, Faulkner’s Light in August and Borges’s short stories. So little intelligence was involved in my daily round of political tasks that I was eager to read difficult works of philosophy and social thought. I began to study the works of Karl Popper, whose The Open Society and its Enemies had come to my attention in 1980. Every day, early in the morning, before going out for my daily run, when it was barely daylight and the quiet of the house reminded me of the pre-political period of my life, I read Popper.

At night, before going to sleep, I read poetry – always the classics of the Spanish Golden Age, and usually Góngora. It was a purifying bath. I stepped away from arguments, plots, intrigues, invectives, and was welcomed into a perfect world, resplendently harmonious, inhabited by nymphs and villains, full of coded references to Greek and Roman fictions, of subtle music and bare, spare architectures. I had read Góngora since my university years with a rather distant admiration; his perfection seemed to me a touch inhuman and his world too cerebral and chimerical. But now I was grateful to him for being abstract and remote, for having built a Baroque enclave outside of time, suspended in an illustrious realm of intellect and sensibility, emancipated from the ugly, the mean and petty, the mediocre, from the sordid facts of daily life.

Between the first and second rounds of the election, I was unable even to do my morning reading, although I tried, sitting down in my study with Popper’s Conjectures and Refutations or Objective Knowledge in my hands. I was preoccupied with the campaign, with the news of murders and of attempts on people’s lives – over a hundred people, many with ties to Libertad, were assassinated in a two-month period. I had to give up my morning reading. But not a single night, not even the night of the election, went by without my reading a sonnet of Góngora’s, or a strophe of his Polifemo or his Soledades, or one of his ballads or rondelets; and through these verses, my life became purer, even though it was only for a few minutes.

Allow me to put on record my enduring gratitude to the great Cordovan poet.

7

Campaigning in the Andes was difficult. To avoid being ambushed, we had to move suddenly and unexpectedly, with a small party, sending someone in advance to alert the most reliable people at our destination that we would be arriving in one or two days’ time. It was impossible to go overland to many provinces of the central mountain region – Junín had become, after Ayacucho, the departamento victimized by the most attacks. The journey had to be made in small planes that landed in unimaginable places – cemeteries, soccer fields, river beds – or in light helicopters which, if a storm suddenly overtook us, had to set down wherever they could – on top of a mountain sometimes – until the weather cleared. These acrobatics completely unnerved some of my colleagues. Beatriz Merino took out crosses, rosaries and holy images she wore over her heart and invoked the protection of the saints at the top of her voice. Pedro Cateriano intimidated the pilots into giving him reassuring explanations about the flight instruments and kept pointing out the threatening thunderheads, the sharp peaks that suddenly loomed up or the snaky rays of lightning that zigzagged all about us.

The central Andes had been subjected constantly to terrorism and counterterrorism. One by one, roads were disappearing because no one maintained them or because the Sendero Luminoso had blown up the bridges with dynamite and blocked the trails so as to stop all traffic. Sendero Luminoso had also destroyed crops and livestock, wrecked buildings and killed off hundreds of vicuñas that used to graze on the reserve of Pampa Galeras and pillaged agricultural co-operatives – principally those of the Valle de Mantaro, the most dynamic in the high country. Sendero Luminoso had assassinated agents from the ministry of agriculture and foreign experts in rural development. It had murdered small-scale farmers and miners, blown up tractors, power plants and hydroelectric installations. It had killed the cattle and it had killed members of the co-operatives and communes who opposed Sendero Luminoso’s scorched-earth policy, which was intended to throttle the cities to death, Lima above all, by allowing no food to reach them.

Words are inadequate. Expressions such as ‘subsistence economy’ or ‘critical poverty’ do not convey the extent of human suffering, the impoverishment of the environment, the utter lack of hope. Entire families were fleeing these Andean villages, their walls daubed with the hammer and sickle and the slogans of the Sendero Luminoso, abandoning everything, driven half mad with desperation because of the violence and poverty. They were heading, armies of unemployed, for our ‘new towns’ – slums, shanty settlements on the outskirts of the cities – swelling them, overcrowding them, as though survivors of some Biblical catastrophe. I often thought: ‘A country can always be worse off. Underdevelopment is bottomless.’

I remember the young, little soldier, practically a child, whom they brought to me at the abandoned airport of Jauja, on 8 September 1989, so that we could take him back to Lima with us. He had survived an attack that noon in which two of his friends had died – we had heard the bombs and the shots from the platform where we were holding our rally – and he was now losing a lot of blood. We made room for him in the small plane by asking one of the bodyguards to stay behind. The boy was obviously under the army’s minimum age of eighteen. He was holding a container of serum up above him, but his strength gave out, and we took turns holding it up. He didn’t complain once during the flight. He stared blankly into space, with an astounded, wordless desperation, as though trying to understand what had happened to him.