It had been raining for weeks. People had forgotten the last morning when the sky was not draped low over the rooftops of England like a giant washcloth. The days were so dark that the only sign of nightfall was the slow brightening of lights in people’s windows.

Rain turned the flat farmland of East Anglia into corrugated paddy fields, with standing water in every furrow. In London, people who lived in basements came home to find that their carpets had turned black with damp as the water-table rose.

Travel agents liked it. Their carousels of brochures showing places in the sun were stripped bare by customers in Barbour coats and green wellington boots. Everyone who could find an excuse to be abroad on business was leaving the country, with the weathermen saying that they could see no change in the foreseeable future. Tomorrow, there would be more rain, with more rain moving in at the weekend. On television, there were pictures of punts afloat in village streets and men in oilskins carrying pensioners to safety. Going anywhere on the Underground was an unpredictable adventure because of flooding in the tunnels.

Then the storm came. It began as a vacuum in the atmosphere, far out over the Atlantic. Trying to fill itself, it set up a spinning mass of air, like a plughole sucking water from a bath; but the faster the winds blew, the more the vacuum deepened. It was an insatiable emptiness. It sucked and sucked; the air spiralled around it; the hole got bigger.

It did its best to flatten a corner of north-western France, then raced across the Channel, from the Cherbourg peninsula to the Dorset coast. Its edge was a jet stream of southerly air, weighted and thickened with moisture from the ocean. When it hit, it had the impact of a runaway truck. It made walls balloon and totter, then threw the bricks about like confetti. It lifted roofs off schools, ripped power lines away from their pylons and let them blow free, lighting the night with flashes of St Elmo’s Fire. Along the edge of the sea, it rained boats and caravans; sixty miles inland, the wind pasted windows with a grey rime of salt from the Atlantic.

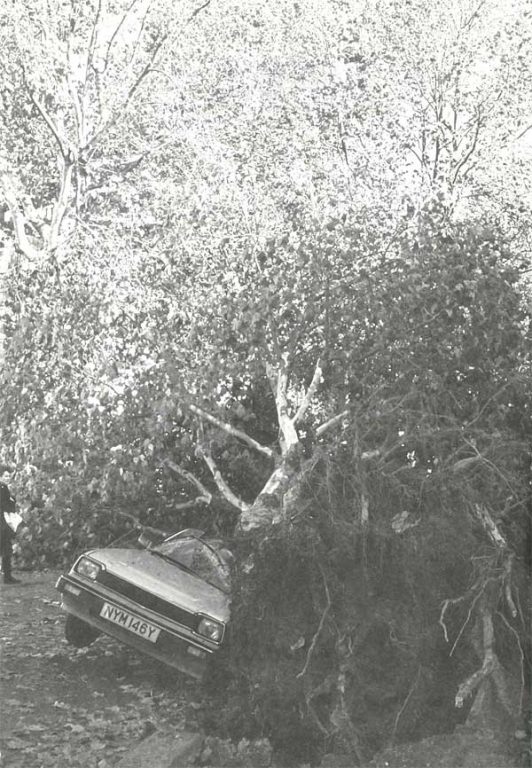

The trees were still in leaf. After the many days of rain they were rooted in soft mud that released even full-grown oaks as if they were seedlings in a gardener’s tray. On south-facing hillsides, whole woods were plucked out of the soil by the wind and strewn in heaps, ready for the chainsaw.

The cyclone worked its way towards the Home Counties. By two in the morning it was on the outskirts of London, where its first victim was a goat in Woking. The goat lived in a kennel, lovingly disguised by its builder as a miniature Tudor cottage, complete with half-timbering and painted thatch. The wind seized this piece of fond make-believe and tossed it skywards. No one knew for how long the goat and its cottage had been in flight, but both were found the next morning, five gardens away, with the dead goat hanged by its chain. There were several human deaths in the storm, including a tramp who was killed by a falling wall in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but the story of the flying goat gained most coverage in the popular papers.

Some people slept through the storm, mistaking the commotion for a turmoil inside themselves. They dreamed violent dreams. Others sat up through the night in dressing gowns, making cups of tea and listening to the falling slates, the windows shaking in their frames, the oboe and bassoon noises of the wind as it blew down narrow streets and funnelled through the gaps between houses. Older people heard the falling trees as bombs. They huddled downstairs, waiting mutely for the first soft crump, then the flying glass, the shaking walls, the sudden entry of the open sky – but there were no wardens, no sirens; it was lonelier, more eerie than the Blitz.

No one dared go outside. You couldn’t open the door against that wind, and who in his right mind would want to face the skirl of tiles, dustbins, garden furniture and plant pots? So people sat tight. In the suburbs, telephones went dead in the middle of a comforting chat with the neighbours. Electric lights dickered and snuffed out. Old candles were discovered in tool drawers. People who cooked by electricity remembered Primus stoves at the backs of cupboards. Just so long as you can boil a kettle, people said, that’s the main thing, isn’t it? Camping out in their houses, brewing tea, talking in low voices and listening to the wind, they surprised themselves with the cosiness of it all. At three and four in the morning, husbands and wives who’d grown as used to each other as they were to their curtains and carpets found themselves reaching for each other’s nakedness.

Soon after dawn, the storm quit London, leaving a high wind blowing under a sky of bad milk. Light-headed from lack of sleep, people stared through their salt-caked windows to see cars crushed by trees and craters of muddy water in the pavements where the trees had been. Roads were strewn with tiles and broken bricks, bits of picket fencing, garden shrubs, upended tricycles, glass, tarpaper, fish bones, cardboard boxes. During what the radio news now called The Hurricane, everyone’s rubbish had mated with everyone else’s, and white stucco house fronts were curiously decorated with dribbles of gravy, tomato ketchup and raspberry yogurt.

On the Saturday morning, a day after the passage of the cyclone, Hyde Park was closed to traffic. The Carriage Road and The Ring were blocked by dozens of crashed trees, and the police had put up Danger signs on trestles to warn people away from the open craters and the trees that were still falling, slowly, their enormous roots half in, half out of the ground. The park was as noisy as a logging camp, and its resiny smell of sawn timber drifted deep into the city, to shoppers on Oxford Street and motorists caught in the jam on Brompton Road. There was allure in the smell alone. People felt themselves drawn to the park without quite knowing why; they ignored the warning signs; they stepped easily over the barriers of red tape that the police had strung between the trestles, and each one felt a surge of private exultation at the sight of what the storm had done.

It’s so sad! people said, trying to quench their smiles – for they didn’t feel sad at all. They were thrilled by the magnificent destruction of the wind: it was as if the world itself had come tumbling down, and even the shyest, most pacific people in the crowd felt some answering chord of violence in their own natures respond to this tremendous and unlooked-for act of violence in nature itself.

The sky had lifted. A meagre ration of diffused sunlight – the first for many days – lit the scene of an anarchic picnic. Children in coloured blousons swarmed in the branches of the humbled trees. Muddy dogs, tongues lolling, scrambled out of the craters. A black-and-white striped Parks Police van patrolled the bank of the Serpentine, its twin loud hailers yawping about risk, responsible, and in your own best interests; but its presence only added to the air of carnival.

Whoever you were, the wrecked landscape had something in it for you personally. For some people, it was simply an enjoyable reminder of their grace – they’d got away with it; they were survivors. They strode across the skyline of the park like generals on a battlefield after a famous victory. Others stood still, gazing, hands in pockets. Exiles, from Beirut, Kampala, Prague, Budapest, felt a proud glow of kinship with the uprooted trees. Saturday fathers, borrowing children from their one-time wives, dwelled, with a pleasure they couldn’t explain to themselves, on the ragged pits in the earth, the torn turf, the canopies of exposed roots; while their children saw the park as a territory at last made fit for all-out war, and zapped their fathers with death-ray guns from behind safe jungle cover. Everyone was irrationally happier that Saturday, even the people who’d lost their roofs, who saw themselves as heroes of the hurricane and came to the park to enjoy disaster on a scale grand enough to match their own. Isn’t it sad? they said, their voices drowned by shrilling gulls circling the trees that still survived.

Photograph © De Keerle (Frank Spooner)