Consider me a bruise, a swollen wound, purpled and puffy. I wish that would inform how people brush up against me in this world, how they touch me, the pressure with which they press. Marguerite tells me often how strong I am, and how fragile. I’m not interested in resilience, but in how to move through this world with reciprocal tenderness, even though this only works with people interested in the same thing. It’s fine. I’ve never been the type of god to waste time on attempted conversions.

We’ve talked briefly about the paranoia that develops in times like this, and I wonder if it counts as paranoia when it’s warranted – the shields we have to throw up, the calculations of harm we have to make, predicting where we will need to be protected. My therapist wants me to trust my own assessments instead of consulting my friends, because I tend to believe them more than myself. I’ve spent most of my life watching the world try to convince me that it’s not doing anything to me, that I’m making things up, that I’m wrong and too sensitive, so I tell her it’s a little scary to allow for the possibility that I am equipped to make decisions alone. In that solitude, there are so many voices whispering that I’m crazy, but now I wonder, how bad would it really be to be mad and safe? Does it matter if everyone else thinks you’re insane if you’re well and at peace? Is one of the sacrifices the self that I am in other people’s eyes? What if I make it so that I only exist in my own gaze?

As my visibility has increased, my needs around safety have changed quickly enough to leave me disorient d. I know I’m not alone. I’ve been watching other people ascend at a steady and plotted speed, after years and years of doing the work, and I’ve seen their shock at the betrayals that came with that. My reaction to this accumulation of power or shine or whatever we want to call it is to retreat. I am a bruise and people are rough. I might have always been a bruise and just lost the capacity to pretend to be anything else.

I moved to the swamp so I could disappear a little. New York was too much; I couldn’t leave home without worrying about being recognized. The first week in my last apartment there, I got recognized while walking to the Rite Aid on the corner, wearing an ankle-length winter coat. Once Freshwater came out, the list of places in the city became long and random: while checking out at the Whole Foods on Houston, while biking through SoHo, while having an intimate conversation with my best friend on the L train. Once, a woman followed me into a nail salon to confront me about an interview that my agents had canceled with the magazine that hired her, accusing me of standing her up. I’d never even corresponded with her; I’m not the one who sets up my meetings. I remember standing there with a bottle of nail polish in my hand, listening to her tell me how she saw me on the street and decided to follow me into the salon, and all I could think was that I was only in town for twenty-four hours, I was sick and exhausted, and the last thing I needed was to suddenly slap on the mask of my public persona to placate a complete stranger. I should have told her to leave me the fuck alone, but that would have been a whole thing, so I played along apologetically until she left. I swear, at some point when all people can see is your public persona, you stop being a person. I’m writing this letter to you because it’s invaluable to not feel alone when thousands of eyes are watching.

I used to think I wanted to be famous. Now I think I just want to be safe, with enough resources to build even more safety around myself. Embodiment is war, in a sense. At some point, everyone is capable of snarling at you with nothing in their head past survival; you just have to back them into the right corners, to see it roar forward. Something about this kind of visibility does feel like a corner, even if it looks like wings to everyone else. There is so much that’s unseen: the way it feels to never know who’s watching you, the hesitation in speaking about it because there’s always someone who thinks it’s not that serious and you’re not that big of a deal to be making this much of a fuss. The godforsaken isolation, the chasms that now stretch between you and everyone who doesn’t want to admit your life has morphed into something neither of you quite recognize anymore, between you and those who want to use you, between you and those whose desires you can’t quite read and therefore don’t quite trust. I retreat from all of it because it’s safer to just not gamble at all. I don’t trust people, and masks can be adept things. I’m okay with being this guarded, whether other people agree that it’s necessary or not. My therapist would be proud. I draw boundaries like scything fire, making a moat of flame around me; I am a dragon in a golden lair; I am inaccessible and unavailable.

Tamara teaches me about insulation, which is really a lesson about community. ‘You should never go anywhere alone,’ she says. Her family has been in Brooklyn for more than a hundred years; she tells me about her and her cousins insulating each other. On the night of the Freshwater launch, she met me outside with a green juice; she taught me how to take care of my flesh after expending such energy. In New York, either she or Alex come with me to readings, galas, and shoots. It makes such a difference, I am stunned. I tell my agents I won’t travel without a companion coming with me or waiting at my destination. Ann meets me in LA; you meet me in San Francisco; Alex flies with me to Boston. When Tiona came to town and we did the NY Art Book Fair together, she gave me one of her anxiety gummies before we walked in. There were s many people there, it was ridiculous. She reached out to hold my hand as we walked, and I remember feeling proud that I could show up as her insulation, buffer her against the massed crowds pushing through the building. It was, I think, forty-eight hours after the magician had thrown me in the ring. I was fragile but I could be useful, and that is something that I think is important, to shield the people we care about. While Tiona and I were signing books, a mutual acquaintance delivered a photograph of myself with the magician. I was entirely too fragile to see his face unexpectedly, this poison of a love. Tamara had just been by our table. As soon as Tiona saw the photo, she took it away and called Tamara back. ‘You need to get rid of it,’ she told her, and Tamara took it without asking any questions. Later, I asked her what she did with it. ‘I threw it away,’ she said, unrepentant about not asking me first, unrepentant about protecting me. I loved her, and Tiona, very much for that. What is love if not a shield thrown up around you when you are too injured to throw it up yourself?

How far will we go to protect ourselves? I am fine-tuning all my shields, making a bubble around me that only vetted people can enter. Two years into my career, my team and I develop protocols. I communicate mostly through my agents – often, organizers have no way to reach me until I physically show up at events. When I have phone interviews, they send me the interviewer’s number instead of sending them mine. I have two phones, four and a half numbers, unidentified calls are unanswered knocks on the door. I am not really here in the first place, too absent to reply to messages from strangers on social media, too much of a dragon to entertain people trying to bypass my agents. ‘We prefer more of a personal touch,’ one of them writes. ‘Working with agents can be a little tedious,’ another suggests. It makes no difference; the protocol is protocol for a reason. I’m not here. I am here and too much of a bruise. I put an out-of-reality message on my email, and for months I just don’t take it off. I don’t call my father, not even out of duty. I’m not here. I can’t imagine becoming more present, only fading out more and more. Am I trying to become a ghost? Can I haunt my own home? Is that happiness?

Maybe all of this makes no sense; maybe it makes all the sense in the world. I don’t care anymore. It’s what I want, to be in a compound blocked out by tall bamboo and vines, have my people come and visit, write these books in the godhouse until the swamp takes us all. Maybe I’m being morbid since my heart was broken. I used to dream of traveling, and then I traveled and splintered along the way. Now, I’ll do whatever it takes to feel safe. The dead magician doesn’t have my heart, so I’m free. It’s just a silly lifetime, it’s just a few decades. If the doubters don’t see how hungry people are, how they will reach and reach for you till there’s nothing left, then they must be lucky to not know. I trusted people before, I thought they would understand when I kept telling them I was falling quiet because I wasn’t okay, because my life was mutating too fast, too painfully, but then I saw how quickly people lash out when you restrict their access to you. It gets so ugly, this thing of punishing others for prioritizing their well-being over reassuring insecurities. I’ve been on the other side; I know that particular blindness.

We can’t save everyone; we might not b able to save anyone.

I gave a talk at Yale recently, and at the reception afterward, a woman told me about a paper she wrote on Freshwater, how she was taking it to a medical conference to argue for recognizing indigenous realities in treating people. It made me so happy, because it felt like a ripple, you know? You make one thing, and someone makes something else from that, and from there the world is changed, one fraction at a time. It reminded me that I send the work out as a proxy, which is part of the protection. The work is of me, but it’s not me, and that’s perfect because it can’t hurt like me, it can’t be broken or bruised. It’s invincible, really – tens of thousands of copies swirling through the world, spells dripping into people. I’ve let that absolve me for not being able to do more myself, for the limitations of the flesh, the ways I couldn’t afford to be a messenger crammed into planes, spreading this gospel with my own mouth. I’d rather be a dragon. I’d rather keep making the stories and sending them out like an army, waves and waves over the hills like a million monsters with salvation under their tongues. All this has taught me to trust myself faster than I might have learned otherwise. No one else knows what is hunting us, what we are keeping at bay, what the constant onslaughts feel like or where they are coming from. It is only us and the fires we set between our homes and the encroaching dark, the rubber of a machete handle gripped against our lifelines.

We move.

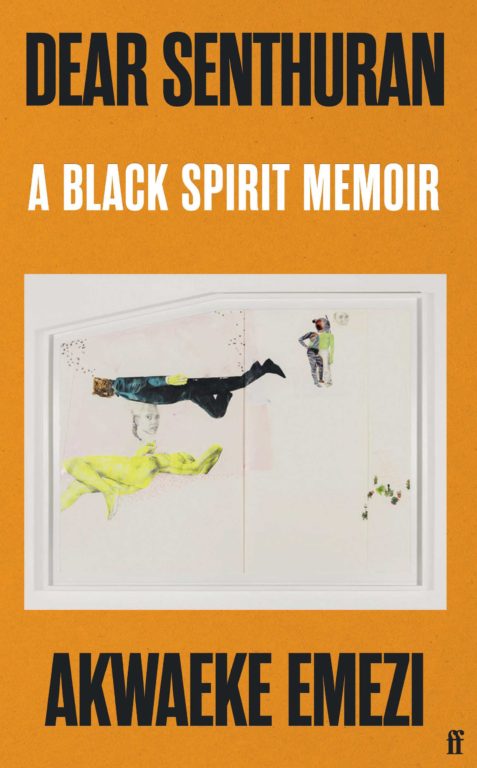

Image © Julien Desclaux

This is an excerpt from Dear Senthuran: A Black spirit memoir by Akwaeke Emezi, published by Faber.