I come from Saint-Sourd-en-Ger, madame, a place where no one lies about

In Saint-Sourd, when I was a child, there were the coal pits and the Prosper Ginot theater company

You’d see the actors from the Comédie de Saint-Sourd go by in the town square. They walked alone or in pairs

Especially on Sundays, on account of the market

I could always say their names

I murmured them to myself, Armand Cheval, Prosper Ginot, Madeleine Puglierin, Désiré Guelde, Georgia Glazer, Odette Ordonneau

I recognized them all

. . .

Here I am, cavorting. Almost

Yes . . .

Will they put my titanium knee joint in the urn after I’m cremated?

I’ve been wondering

People in the know, madame, say the soul leaves the body right away and you see yourself

You see yourself lowered into the ground

That’s why I say cremation

I’ve had a happy life, you know

My whole knee is titanium, they only left the kneecap

The doctor said, you’re almost good as new, you can give the cane a rest

Get that thing out of my sight!

For me a cane means polio

Deformed kids with gimpy legs creeping around Saint-Sourd, hugging the walls

I lived in terror of polio my whole childhood

The slightest twinge and I had polio

Or sometimes it was cancer, or meningitis

But mostly I had polio

I’d never have received you with the cane. You don’t mind the slippers?

They’re Furlanes

Gondolier slippers from Venice. I have yellow ones too

When my husband was alive, they lay moldering in the closet

He said they made me look stumpy

With the cane, I’d worked out a quiet little circuit with places to sit down on the way to Picard and the Monoprix

And the beauty parlor for my tint

I sat down at the bakeshop with the little tearoom. I sat at the pharmacy, where they like me. Then at Picard, where they adore me. There was the 84 bus stop with a shelter. And an empty cashier’s seat at the Monoprix

There are three cashiers for five cash desks. They know me there

At the Monoprix, there’s a little evangelical from Madagascar who loves me. Victor. He stacks boxes. He finds whatever I’m looking for

The security guard too – none too swift but nice. He grabs the things I can’t reach. I haven’t got my range of motion back. They keep the compound for polishing the brass under the shelves for lack of space

That Monoprix’s not big enough

They know me there

The new doctor said, you’re pretty much good as new, you can ditch the cane

No sooner said than done!

He says my blood pressure’s a little high

I said, how’s that, doctor, my pressure’s high when it never was before? He said, that’s how it goes. One day we don’t have a thing and the next day we do

I said, oh là, I don’t care for that way of thinking! Dr Olbrecht never thought that way

I miss Olbrecht. We knew each other for thirty years

He used to come see me on stage

He took care of my husband and my son too

At a certain age, it’s as if word gets round and people slip away on you. The ones who were supposed to be there holding your hand till the end. The doctor, the agent, the husband, my neighbors the Storms

The first time, I saw her through a doorway. Lying on a sofa with all that hair

I’d just arrived in the capital from the North to audition at the Théâtre de Clichy

I saw the bent head at the end of the room with the hair tumbling down. She was smoking

Someone said, that’s Giselle Fayolle

I thought she was a big deal, but she was nothing then. Nothing at all

Still, to me a girl with a dressing room in Paris was a big deal

We got to know each other doing Bérénice

I played her confidante

In real life too, I sympathized with her lovers

She lived on rue Émile-Augier, and I had a room on rue des Rondeaux which she never visited

When we met again, forty years later, it was still me going to see her

In the end, Giselle had bowel trouble, and I had the buggered knee

We went out to eat from time to time. Or I went to her place on rue de Courcelles

I even slept there once when she was feeling blue

Always me going to see her

After my surgery, I stopped. No more excursions

Of course it was a shock, madame, seeing her there in black and white

Black and white in magazines means six feet under

We were used to seeing that photo in color

Blue sparkles, all the way to her temples

Back then, rumor had it she was Alain Delon’s mistress

Maybe Ingmar Bergman’s, too

Anyway, tongues wagged

You’re at the pedicure salon and turn a page, expecting something frivolous, and there is Gigi Fayolle in black and white

The obituaries below have no photos

I was fresh off the train from Saint-Sourd, in Paris to audition

No one was playing the confidantes in tragedy. I came recommended

When they gave me Phénice, I was so happy, mademoiselle, incredibly, immeasurably happy because of the feeling of luck

Giselle reclined on a flowery sofa with her hair

I was mesmerized by her hair

She was twenty-one. I was nineteen

She was one of those girls who stay in bed till noon and do everything in bed, eat, talk on the phone, read, receive visitors, and in their dressing room they have a sofa, and they lie down again with their feet up

That was Giselle when I knew her. Lying with a cup of tea and a biscuit within reach

She had a room on Rue Emile Augier, near La Muette. Mine was on rue Rondeaux in the 20th

The street faces the wall of Père Lachaise cemetery. What a view. Like a bullet in the head. I’ve never understood people who can eat just one biscuit. One biscuit, where’s the joy?

She snapped up all the big roles. By lying on her back like a sleeping statue on a tomb, and looking as if there was nothing in the world that she wanted. She got all the queen roles, the madwomen, the whores, and even the colonial floozies. It’s good for your career to look as if you don’t want anything

I gave languor a try, too

But not everyone is cut out for languor

Dr Olbrecht threw parties at his home, with themes. One year it was the desert and the Bédouins. He called a special events planner. He ordered a lorry-load of sand and a multicolored tent. They sat around the living room, Bédouin-style, the doctor’s wife eating dates with their friends on ten inches of sand

I was a little sweet on Olbrecht

His wife up and left him, just like that. What is good for a woman?

I had a nice husband. Uncomplicated

His pet activity was repainting the apartment

He always wanted to repaint, repaint, repaint. He was wild about making things fresh again

I was bored with my husband, but you know, boredom is part of love

He talked to me about his expert appraisals in termite control. We played Scrabble

He was a hundred per cent organized, he could not bear the unforeseen

My husband could not survive without structure. Even a penal structure would have suited him. Electroshock at five, torture at half past six. Those are the rules, so we know what we’re doing. I’d have been content to play la Bédouine with Olbrecht

You play la Bédouine and when you’re a widow, you end up in a hole in the wall with a hot plate and your heap of trinkets

My husband left me two pension and retirement protection plans, plus two life insurance policies in my name. Not to mention a nice three-room flat, a stone’s throw from Place Pereire

But the specter of the wheel that turns is never far

You start out as little people, and you’re little people in the end

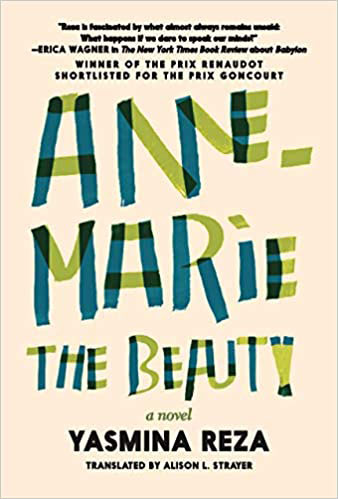

This is an excerpt from Anne-Marie the Beauty by Yasmina Reza, translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer. Out with Seven Stories Press.

Image © Michael Levine-Clark