The heat, as the taxi spiralled the narrow hill bends, became more violent. The road thundered between patches of shade thrown by overhanging rock. Behind the considerable noise of the car, the petulant hooting at each corner, the steady tick-tick of the cicadas spread through the woods and olive groves as though to announce their coming.

The woman sat so still in the back of the taxi that at corners her whole body swayed, rigid as a bottle in a jolting bucket, and sometimes fell against the five-year-old boy who curled, thumb plugged in his mouth, on the seat beside her. The woman felt herself disintegrate from heat. Her hair, tallow blonde, crept on her wet scalp. Her face ran off the bone like water off a rock – the bridges of nose, jaw and cheekbones must be drained of flesh by now. Her body poured away inside the too-tight cotton suit and only her bloodshot feet, almost purple in the torturing sandals, had any kind of substance.

‘When are we there?’ the boy asked.

‘Soon.’

‘In a minute will we be there?’

‘Yes.’

A long pause. What shall we find, the mother asked herself. She wished, almost at the point of tears, that there were someone else to ask, and answer, this question.

‘Are we at France now?’

For the sixth time since the plane had landed she answered, ‘Yes, Johnny.’

The child’s eyes, heavy-lidded, long-lashed, closed; the thumb stoppered his drooping mouth. Oh, no, she thought, don’t let him, he mustn’t go to sleep.

‘Look. Look at the . . .’ Invention failed her. They passed a shack in a stony clearing. ‘Look at the chickens,’ she said, pulling at the clamped stuff of her jacket. ‘French chickens,’ she added, long after they had gone by. She stared dully at the taxi driver’s back, the dark stain of sweat between his shoulder blades. He was not the French taxi driver she had expected. He was old and quiet and burly, driving his cab with care. The price he had quoted for his forty kilometre drive from the airport had horrified her. She had to translate all distances into miles and then apply them, a lumbering calculation, to England. How much, she had wanted to ask, would an English taxi driver charge to take us from London Airport to . . . ? It was absurd. There was no one to tell her anything. Only the child asking his interminable questions, with faith.

‘Where?’ he demanded suddenly, sitting up.

She felt herself becoming desperate. It’s too much for me, she thought. I can’t face it. ‘What do you mean – where?’

‘The chickens.’

‘Oh. They’ve gone. Perhaps there’ll be some more, later on.’

‘But when are we there?’

‘Oh, Jonathan . . .’ In her exasperation, she used his full name. He turned his head away, devouring his thumb, looking closely at the dusty rexine. When her hot, stiff body fell against him, he did not move. She tried to compose herself, to resume command.

It had seemed so sensible, so economical, to take this house for the summer. We all know, she had said (although she herself did not), what the French are – cheat you at every turn. And then, the horror of those Riviera beaches. We’ve found this charming little farmhouse up in the mountains – well, they say you can nip down to Golfe-Juan in ten minutes. In the car, of course. Philip will be driving the girls, but I shall take Johnny by air. I couldn’t face those dreadful hotels with him. Expensive? But, my dear, you don’t know what it cost us in Bournemouth last year, and I feel one owes them the sun. And then there’s this dear old couple, the Gachets, thrown in so to speak. They’ll have it all ready for us, otherwise of course I couldn’t face arriving there alone with Johnny. As it is, we shall be nicely settled when Philip and the girls arrive. I envy us too. I couldn’t face the prospect of those awful public meals with Johnny – no, I just couldn’t face it. And so on. It was a story she had made up in the cold, well-ordered English spring. She could hear herself telling it. Now it was real. She was inadequate. She was in pain from the heat, and not a little afraid. The child depended on her. I can’t face it, she thought, anticipating the arrival at the strange house, the couple, the necessity of speaking French, the task of getting the child bathed and fed and asleep. Will there be hot water, mosquitoes, do they know how to boil an egg? Her head beat with worry. She looked wildly from side to side of the taxi, searching for some sign of life. The woods had ended, and there was now no relief from the sun. An ugly pink house with green shutters stood away from the road; it looked solid, like an enormous brick, in its plot of small vines. Can that be it? But the taxi drove on.

‘I suppose he knows where he’s going,’ she said.

The child turned on his back, as though in bed, straddling his thin legs. Over the bunched hand his eyes regarded her darkly, unblinking.

‘Do sit up,’ she said. His eyelids drooped again. His legs, his feet in their white socks and disproportionately large brown sandals, hung limp. His head fell to one side. ‘Poor baby,’ she said softly. ‘Tired baby.’ She managed to put an arm round him. They sat close, in extreme discomfort.

Suddenly, without warning, the driver swung the taxi off the road. The woman fell on top of the child, who struggled for a moment before managing to free himself. He sat up, alert, while his mother pulled and pushed, trying to regain her balance. A narrow, stony track climbed up into a bunch of olive trees. The driver played his horn round each bend. Then, on a perilous slope, the car stopped. The driver turned in his seat, searching back over his great soaked shoulder as though prepared, even expecting, to find his passengers gone.

‘La Caporale,’ he said.

The woman bent, peering out of the car windows. She could see nothing but stones and grass. The heat seized the stationary taxi, turning it into a furnace.

‘But – where?’

He indicated something which she could not see, then hauled himself out of the driving seat, lumbered round and opened the door.

‘Ici?’ she asked, absolutely disbelieving.

He nodded, spoke, again waved an arm, pointing.

‘Mais . . .’ It was no good. ‘He says we’re here,’ she told the child. ‘We’d better get out.’

They stood on the stony ground, looking about them.

There was a black barn, its doors closed. There was a wall of loose rocks piled together. The cicadas screeched. There was nothing.

‘But where’s the house?’ she demanded. ‘Where is the house? Où est la maison?’

The driver picked up their suitcases and walked away. She took the child’s hand, pulling him after her. The high heels of her sandals twisted on the hard rubble; she hurried, bent from the waist, as though on bound feet. Then, suddenly remembering, she stopped and pulled out of her large new handbag a linen hat. She fitted this, hardly glancing at him, on the child’s head. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘I can’t think where he’s taking us.’

Round the end of the wall, over dead grass; and above them, standing on a terrace, was the square grey house, its shuttered windows set anyhow into its walls like holes in a warren. A small skylight, catching the sun, flashed from the mean slate roof.

They followed the driver up the steps on to the terrace. A few pots and urns stood about, suggesting that somebody had once tried to make a garden. A withered hosepipe lay on the ground as though it had died trying to reach the sparse geraniums. A chipped, white-painted table and a couple of wrought-iron chairs were stacked under a palm tree. A lizard skittered down the front of the house. The shutters and the doors were of heavy black timber with iron bars and hinges. They were all closed. The heat sang with the resonant hum of failing consciousness. The driver put the suitcases down outside the closed door and wiped his face and the back of his neck with a handkerchief.

‘Vous avez la clef, madame?’

‘La clay? La clay?’

He pursed and twisted his hand over the lock.

‘Oh, the key. No. Non. Monsieur and Madame Gachet . . . the people who live in the house . . . Ce n’est pas,’ she tried desperately, ‘ferme.’

The driver tried the door. It was firm. She knocked. There was no answer.

‘Vous n’avez la clef ?’ He was beginning to sound petulant.

‘Non. Non. Parce que . . . Oh dear.’ She looked up at the blind face of the house. ‘They must be out. Perhaps they didn’t get my wire. Perhaps . . .’ She looked at the man, who did not understand what she was saying; at the child, who was simply waiting for her to do something. ‘I don’t know what to do. Monsieur and Madame Gachet . . .’ She pushed back her damp hair. ‘But I wrote to them weeks ago. My husband wrote to them. They can’t be out.’

She lifted the heavy knocker and again hammered it against the door. They waited, at first alertly, then slackening, the woman losing hope, the driver and the child losing interest. The driver spoke. She understood that he was going, and wished to be paid.

‘But you can’t leave us like this. Supposing they don’t come back for hours? Can’t you help us to get in?’

He looked at her stolidly. Furious with him, humiliated by his lack of chivalry, she ran to one of the windows and started trying to prise the shutters open. As she struggled, breaking a fingernail, looking about for some object she could use, running to her handbag and spilling it out for a nail file, a pair of scissors, finding nothing, trying again with her useless fingers, she spoke incessantly, her words coming in little gasps of anger and anxiety.

‘Really, one would think that a great man like you could do something instead of just standing there, what do you think we shall do, just left here in the middle of nowhere after we’ve come all this way. I can tell you people don’t behave like this in England, haven’t you got a knife or something? Un couteau? Un couteau, for heaven’s sake?’

She was almost hysterical. The driver became angry. He picked up her wallet, thrown out of the handbag, and shook it at her. He spoke very quickly. Frightened, she controlled herself. She snatched the wallet from him. She was trembling.

‘Very well. Take your money and go.’ She had not got the exact amount. She gave him ten thousand francs. He nodded, looked over the house once more, shrugged his shoulders and moved away.

‘The change!’ she called. ‘Change . . .’ pronouncing the word, with little hope, in French. ‘L’argent . . .’

‘Merci, madame,’ he said, raising his hand. ‘Bon chance.’

He disappeared down the steps. In a moment she saw him walking heavily, not hurrying, across the grass.

‘Well,’ she said, turning to the child. ‘Well . . .’ She paused, listening to the taxi starting up, the sound of its engine revving as it turned in the stony space, departing, diminishing – gone. The child looked at her. Suspicion, for the first time in his life, darkened and swelled his face. It became tumescent, the mouth trembling, the eyes dilated before the moment of tears.

‘Let’s have some chocolate,’ she said. The half bar fallen from her handbag, had melted completely. ‘We can’t,’ she said, with a little, brisk laugh. ‘It’s melted.’

‘Want a drink.’

‘A drink.’ As though in a strange room, she looked round searching for the place where, quite certainly, there must be drink. ‘Well, I don’t know . . .’ There was a rusty tap in the wall, presumably used for the hose. She pretended not to have seen it. Typhus or worse. She remembered the grapes – they looked far from ripe – that had hung on sagging wires over the steps. ‘We’ll get into the house,’ she said, and added firmly, as though there were no question about it, ‘We must get in.’

‘Why can’t we go into the house?’

‘Because it’s locked.’

‘Where did the people put the key?’

She ran to the door and started searching in the creeper, along the ledge, her fingers recoiling from fear of snakes or lizards. She ran round to the side of the house, the child trotting after her. A makeshift straw roof had been propped up over an old kitchen table. A rusty oil stove stood against the wall of the house. She searched in its greasy oven. She tried the holes in the wall, the dangerous crevices of a giant cactus. The child leant against the table. He seemed now to be apathetic.

‘We’ll go round to the back,’ she said. But at the back of the house there were no windows at all. A narrow gully ran between the house and a steep hill of brown grass. The hill, rising to dense woods, was higher than the roof of the house. She began to climb the hill.

‘Don’t come,’ she called. ‘Stay in the shade.’

She climbed backwards, shading her eyes against the unbearable sun. The child sat himself on the wall of the gully, swinging his legs and waiting for her. She looked down on the glistening roof and saw the small mouth of the skylight, open. She knew, even while she measured it with her eyes, imagined herself climbing through it, that it was inaccessible. Her mind gabbled unanswerable questions: how far is the nearest house? Telephone? How can we get back to Nice? Where does the road lead to? As she looked down at the house, something swift and black, large as a cat, streaked along the gutter, down the drainpipe and into the gully.

‘Johnny!’ she called. ‘Johnny!’ She began to run back down the hill. Her ankle twisted, she fell on the hard grass. She pulled off her sandals and ran barefoot. ‘Get up from there! Don’t sit there!’

‘Why?’

‘I saw . . .’

‘What? What did you see?’

‘Oh, nothing. I think we’ll have to go back to that house we passed. Perhaps they know . . .’

‘What did you see, though?’

‘Nothing, nothing. The skylight’s open.’

‘What’s a skylight?’

‘A sort of window in the roof.’

‘But what did you see?’

‘If there was a ladder, perhaps we could . . .’ She looked round in a worried way, but without conviction. It was to distract the child from the rat.

‘There’s a ladder.’

It was lying in the gully – a long, strong, new ladder. She looked at it hopelessly, disciplining herself to a blow from fate. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I could never lift it.’

The child did not deny this. He asked. ‘When are the people coming back?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘I want some chocolate.’

‘Oh, Johnny!’

‘I want a drink.’

‘Johnny – please!’

‘I don’t want to be at France. I want to go home now.’

‘Please, Johnny, you’re a big man, you’ve got to look after Mummy—’

‘I don’t want to—’

‘Let’s see if we can lift the ladder.’

She jumped down into the gully. The ladder was surprisingly light. As she lifted one end, propping the other against the gully wall, juggled it, hand over hand on the rungs, into position, she talked to the child as though he were helping her.

‘That’s right, it’s not a bit heavy after all, is it, now let’s just get it quite straight, that’s the way . . .’

Supposing, she thought, the Gachets come back and find me breaking into the house like this? You’ve paid the rent, she told herself. It’s your house. It’s scandalous, it’s outrageous. One must do something.

‘Are you going to climb up there?’ the child asked, with interest.

She hesitated. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Yes, I suppose so.’

‘Can I go up the ladder too?’

‘No, of course not.’ She grasped the side of the ladder firmly, testing the bottom rung.

‘But I want to . . .’

‘Oh, Jonathan! Of course you can’t!’ she snapped, exasperated. ‘What d’you think this is – a game? Please, Johnny, please don’t start. Oh, my God . . .’ I can’t face it, she thought, as she stepped off the ladder, pulled herself up on to the grass, held his loud little body against her sweat-soaked blouse, took off his hat for him and stroked his stubbly hair, rocked him and comforted him, desperately wondered what bribe or reward she might have in her luggage, what prize she could offer . . . She spoke to him quietly, telling him that if he would let her go up the ladder and get into the house she might find something, she would almost certainly find something, a surprise, a wonderful surprise . . .

‘A toy.’

‘Well, you never know.’ She was shameless. ‘Something really lovely.’

‘A big toy,’ he stated, knowing his strength.

‘A big toy, and a lovely bath and a lovely boiled egg—’

‘And a biscuit.’

‘Of course. A chocolate biscuit. And a big glass of milk.’

‘And two toys. One big and one little.’

‘Yes, and then we’ll go to sleep, and not tomorrow but the next day Daddy will come . . .’ She felt by the weight against her breast, that she was sending him to sleep. She put him away from her carefully. He lay down, without moving the curled position of his body, on the grass. He sucked his thumb, looking at her out of the corners of his bright eyes. ‘So I’ll climb the ladder. You watch. All right?’

He nodded. She jumped down into the gully again, pulled her tight skirt high above her knees, and started to climb. She kept her eyes away from the gutter. The fear of a rat running close to her made her sick, almost demented with fear. If I see a rat, she thought, I shall jump, I know I shall jump, I can’t face it. She saw herself lying dead or unconscious in the gully, the child left completely alone. As she came level with the roof she heard a sound, a quick scuttering; her feet seemed steeped in hot glycerine, her hands weakened. She lay for a moment face downwards on the ladder, certain that when she opened her eyes she would be falling.

When she dared to look again, she was amazed to see how near she was to the skylight – little more than a yard. This distance, certainly, was over burning slate, much of it jagged and broken. But the gutter was firm, and the gradient of the roof very slight. In her relief, now edged with excitement, she did not assess the size of the skylight. The ladder, propped against the gully wall, was steady as a staircase. She mounted two more rungs and cautiously, with one foot, tested the gutter. Now all she had to do was to edge, then fling herself, forward; grasp the sill of the skylight and pull herself up. She did this with a new assurance, almost bravado. She was already thinking what a story it would be to tell her husband; that her daughters – strong, agile girls – would certainly admire her.

She lay on the roof and looked down through the skylight. It was barely eighteen inches wide – perhaps two feet long. She could no more get through it than a camel through a needle’s eye. A child, a thin child, could have managed it. Her younger daughter could have wormed through somehow. But for her it was impossible.

She looked down at the dusty surface of a chest of drawers. She could almost touch it. Pulling herself forward a little more she could see two doors – attics, no doubt – and a flight of narrow stairs descending into semi-darkness. In her frustration she tried to shake the solid sill of the skylight, as though it might give way. It’s not fair, she cried out to herself; it’s not fair. For a moment she felt like bursting into tears, like sobbing her heart out on the high, hard shoulder of the house. Then, with a kind of delight, she thought – Johnny.

She could lower him through. He would only have to run down the stairs and unbolt one of the downstairs windows. A few weeks ago he had locked himself in the lavatory at home and seemed, for a time, inaccessible. But she had told him what to do, and he had eventually freed himself. Even so, I don’t believe you can do this, she told herself. I don’t believe you can risk it. At the same time, she knew that she had thought of the obvious – it seemed to her now the only – solution. Her confidence was overwhelming. She was dealing with the situation in a practical, courageous way. She was discovering initiative in herself, and ingenuity.

She came quickly, easily down the ladder. The boy was still curled as she had left him. As she approached, smacking the dust and grime from her skirt, he rolled on to his back, but did not question her. She realised with alarm that he was nearly asleep. A few minutes more and nothing would rouse him. She imagined herself carrying him for miles along the road. Already the heat was thinning. The cicadas, she noticed, were silent.

‘Johnny,’ she said. ‘Would you like to climb the ladder?’

His eyes focused, but he continued to suck his thumb.

‘You can climb the ladder, if you like,’ she said carelessly.

‘Now? Can I climb it now?’

‘Yes, if you want to.’

‘Can I get through the little window?’

She was delighted with him. ‘Yes. Yes, you can. And, Johnny . . .’

‘What?’

‘When you’ve got through the little window, I want you to do something for me. Something very clever. Can you do something clever?’

He nodded, but looked doubtful.

She explained, very carefully, slowly. Then, taking his hand, she led him round to the front of the house. She chose a window so near the ground that he could have climbed through it without effort from the outside. She investigated the shutters, and made certain that they were only held by a hook and eyelet screw on the inside. She told him that he would have to go down two flights of stairs and then turn to the right, and he would find the room with the window in it. She tied her handkerchief round his right wrist, so that he would know which way to turn when he got to the bottom of the stairs.

‘And if you can’t open the window,’ she said, ‘you’re to come straight back up the stairs. Straight back. And I’ll help you through the skylight again. You understand? If you can’t open the window, you’re to go straight back up the stairs. All right?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Can I climb the ladder now?’

‘I’m coming with you. You must go slowly.’

But he scaled it like a monkey. She cautioned him, implored him, as she climbed carefully. ‘Wait, Johnny. Johnny, don’t go so fast. Hold on tightly. Johnny, be careful . . .’ At the top, she realised that she should have gone first. She had to get round him in order to reach the skylight and pull him after her. She was now terribly frightened, and frightened that she would transmit her fear to him. ‘Isn’t it exciting?’ she said, her teeth chattering. ‘Aren’t we high up? Now hold on very tightly, because I’m just going to . . .’

She stepped round him. It was necessary this time to put her full weight on the gutter. If I fall, she thought clearly, I must remember to let go of the ladder. The gutter held, and she pulled herself up, sitting quite comfortably on the edge of the skylight. In a moment she had pulled him to her. It was absurdly easy. She put her hands under his arms, feeling the small, separate ribs. He was light and pliable as a terrier.

‘Remember what I told you.’

‘Yes.’ He was wriggling, anxious to go.

‘What did I tell you?’

‘Go downstairs and go that way and open the window.’

‘And supposing you can’t open the window?’

‘Come back again.’

‘And hurry. I’ll count. I’ll count a hundred. I’ll go down and stand by the window. You be there when I’ve counted a hundred.’

‘All right,’ he said.

Holding him tightly in her hands, his legs dangling, his shoulders hunched, she lowered him until he stood safely on the chest of drawers. When she let go he shook himself, and looked up at her.

‘Can you get down?’ she asked anxiously. ‘Are you all right?’

He squatted, let his legs down, slid backwards on his stomach and landed with a little thud on the floor.

‘It’s dirty down here,’ he said cheerfully.

‘Is it all right, though?’ She had a new idea, double security. ‘Run down those stairs and come back, tell me what you see.’

Obediently, he turned and ran down the stairs. The moment he had gone, she was panic-stricken. She called, ‘Johnny! Johnny!’ her head through the skylight, her body helpless and unable to follow. ‘Come back, Johnny! Are you all right?’

He came back almost immediately.

‘There’s stairs,’ he said, ‘going down. Shall I go and open the window now?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘And hurry.’

‘All right.’

‘I’m beginning to count now!’ And loudly, as she slid back to the ladder, she called, ‘One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . .’ Almost at the bottom, her foot slipped, she tore her skirt. She ran round to the front of the house, and as she came up to the window she began calling again in a bold voice, rough with anxiety, ‘Forty-nine . . . fifty . . . fiftyone . . .’ She hammered with her knuckles on the shutter, shouting, ‘It’s this window, Johnny! Here, Johnny! This one!’

Waiting, she could not keep still. She looked at the split in her skirt, pushed at her straggled hair; she banged again on the shutters; she glanced at her watch; she looked up again and again at the blank face of the house.

‘Sixty-eight . . . sixty-nine . . . seventy . . .!’

She sucked the back of her hand, where there was a deep scratch; she folded her impatient arms and unfolded them; she knocked again, calling, ‘Johnny! Johnny! It’s this one!’ and then, in a moment, ‘I’ve nearly counted a hundred! Are you there, Johnny?’

It’s funny, she thought, that the crickets should have stopped. The terrace was now almost entirely in shadow. It gets dark quickly, she remembered. It’s not slow. The sun goes, and that’s it: it’s night-time.

‘Ninety . . . ninety-one . . . ninety-two . . . Johnny? Come on. Hurry up!’

Give him time, she told herself. He’s only five. He never can hurry. She went and sat on the low wall at the edge of the terrace. She watched the minute hand of her watch creeping across the seconds. Five minutes. It must be five minutes. She stood up, cupping her hands round her mouth.

‘A hundred!’ she shouted. ‘I’ve counted a hundred!’

An aeroplane flew high, high overhead, where the sky was the most delicate blue. It made no sound. There was no sound. As though she were suddenly deaf she reached, stretched her body, made herself entirely a receptacle for sound – a snapping twig, a bird hopping; even a fall of dust. The house stood in front of her like a locked box. The sunlight at the end of the terrace went out.

‘Joh-oh-oh-nny! I’m here! I’m down here!’

She managed to get two fingers in the chink between the shutters. She could see the rusty arm of the hook. But she could not reach it. The shutters had warped, and the aperture at the top was too small for anything but a knife, a nail file, a piece of tin.

‘I’m going back up the ladder!’ she shouted. ‘Come back to the skylight! Do you hear me?’

One cicada began its noise again; only one. She ran round to the back of the house and for the third time climbed the ladder, throwing herself without caution on to the roof, dragging herself to the open skylight. There was a wide track in the dust, where he had slid off the chest of drawers.

‘Johnny! Johnny! Where are you?’

Her voice was deadened by the small, enclosed landing. It was like shouting into the earth. There was no volume to it, and no echo. Without realising it, she had begun to cry. Her head lowered into the almost total darkness, she sobbed, ‘Johnny! Come up here! I’m here, by the skylight, by the little window!’

In the silence she heard, quite distinctly, a tap dripping. A regular, metallic drip, like torture. She shouted directions to him, waiting between each one, straining to hear the slightest sound, the faintest answer. The tap dripped. The house seemed to be holding its breath.

‘I’m going down again! I’m going back to the window!’

She wrestled once more with the shutters. She found a small stick, which broke. She poked with her latchkey, with a comb. She dragged the table across the terrace and tried, standing on it, to reach the first floor windows. She climbed the ladder twice more, each time expecting to find him under the skylight, waiting for her. It was now dark. Her strength had gone and her calls became feeble, delivered brokenly, like prayers. She ran round the house, uselessly searching and shouting his name. She threw a few stones at the upper windows. She fell on the front door, kicking it with her bare feet. She climbed the ladder again and this time lost her grip on the gutter and only just saved herself from falling. As she lay on the roof she, became dizzy and frightened, in some part of her, that she was going to faint. The other part of her didn’t care. She lay for a long time with her head through the skylight, weeping and calling, sometimes weakly, sometimes with an attempt at command; sometimes, with a desperate return of will, trying to force herself through the impossible opening.

For the last time, she beat on the shutters, her blows as puny as his would have been. It was three hours since she had lowered him through the skylight. What more could she do? There was nothing more she could do. At last she said to herself, something has happened to him, I must go for help.

It was terrible to leave the house. As she stumbled down the steps and across the grass, which cut into her feet like stubble, she kept looking back, listening. Once she imagined she heard a cry, and ran back a few yards. But it was only the cicada.

It took her a long time to reach the road. The moon had risen. She walked in little spurts, running a few steps, then faltering, almost loitering until she began to run again. She remembered the pink house in the vineyard. She did not know how far it was; only that it was before the woods. She was crying all the time now, but did not notice it, any more than she was aware of her curious, in fact alarming, appearance. ‘Johnny!’ she kept sobbing. ‘Oh, Johnny.’ She began to trot, keeping up an even pace. The road rose and fell; over each slope she expected to see the lights of the pink house. When she saw the headlamps of a car bearing down on her she stepped into the middle of the road and beat her arms up and down, calling, ‘Stop! Stop!’

The car swerved to avoid her, skidded, drew up with a scream across the road. She ran towards it.

‘Please! . . . Please! . . .’

The faces of the three men were shocked and hostile. They began to shout at her in French. Their arms whirled like propellers. One shook his fist.

‘Please . . .’ she gasped, clinging to the window. ‘Do you speak English? Please do you speak English?’

One of the men said, ‘A little.’ The other two turned on him. There was uproar.

‘Please. I beg of you. It’s my little boy.’ Saying the words, she began to weep uncontrollably.

‘An accident?’

‘Yes, yes. In the house, up there. I can’t get into the house—’

It was a long, difficult time before they understood; each amazing fact had to be interpreted. If it had been their home, they might have asked her in; at least opened the door. She had to implore and harangue them through a half-open window. At last the men consulted together.

‘My friends say we cannot . . . enter this house. They do not wish to go to prison.’

‘But it’s my house – I’ve paid for it!’

‘That may be. We do not know.’

‘Then take me to the police – take me to the British Consul—’

The discussion became more deliberate. It seemed that they were going to believe her.

‘But how can we get in? You say the house is locked up.

We have no tools. We are not—’

‘A hammer would do – if you had a hammer and chisel—’

They shook their heads. One of them even laughed.

They were now perfectly relaxed, sitting comfortably in their seats. The interpreter lit a cigarette.

‘There’s a farm back there,’ she entreated. ‘It’s only a little way. Will you take me? Please, please, will you take me?’

The interpreter considered this, slowly breathing smoke, before even putting it to his friends. He looked at his flat, black-faced, illuminated watch. Then he threw the question to them out of the corner of his mouth. They made sounds of doubt, weighing the possibility, the inconvenience.

‘Johnny may be dying,’ she said. ‘He must have fallen. He must be hurt badly. He may’ – her voice rose, she shook the window – ‘he may be dead . . .’

They opened the back door and let her into the car.

‘Turn round,’ she said. ‘It’s back there on the left. But it’s away from the road, so you must look out.’

In the car, since there was nothing she could do, she began to shiver. She realised for the first time her responsibility. I may have murdered him. The feeling of the child as she lifted him through the skylight came back to her hands: his warmth. The men, embarrassed, did not speak.

‘There it is! There!’

They turned off the road. She struggled from the car before it had stopped, and ran to the front door. The men in the car waited, not wishing to compromise themselves, but curious to see what was going to happen.

The door was opened by a small woman in trousers.

She was struck by the barrage of words, stepped back from it. Then, with her myopic eyes, she saw the whole shape of distress – a person in pieces. ‘My dear,’ she said. ‘My dear . . . what’s happened? What’s the matter?’

‘You’re English? Oh – you’re English?’

‘My name’s Pat Jardine. Please come in, please let me do something for you—’ Miss Jardine’s handsome little face was overcast with pain. She could not bear suffering. Her house was full of cats; she made splints for sparrows out of matchsticks. If her friend Yvonne killed a wasp, Miss Jardine turned away, shutting her eyes tight and whispering, ‘Oh, the poor darling.’ As she listened to the story her eyes filled with tears, but her mind with purpose.

‘We have a hammer, chisel, even a crowbar,’ she said. ‘But the awful thing is, we haven’t a man. I mean, of course we can try – we must try – but it would be useful to have a man. Now who can I—?’

‘There are three men in the car, but they don’t speak English and they don’t—’

Miss Jardine hurried to the car. She spoke quietly but passionately, allowing no interruption. Another woman appeared, older, at first suspicious.

‘Yvonne,’ Miss Jardine said, breathlessly introducing her. ‘Get the crowbar, dear, and the hammer – and perhaps the axe, yes, get the axe—’ At the same time she poured and offered a glass of brandy. ‘Drink this. What else do we need? Blankets. First-aid box. You never know.’

‘Thank you. Thank you.’

‘Nonsense, I’m only glad you came to us. Now we must go. Yvonne? Have you got the axe, dear?’

The three men had got out of the car and were standing about. They looked, in their brilliant shirts and pointed shoes, their slight glints of gold and chromium, like women on a battlefield – at loss. Yvonne and Miss Jardine clattered the great tools into the boot. Miss Jardine hurried away for a rope. The men murmured together, and laughed quietly and self-consciously. When everything was ready they got into the car. The three women squeezed into the back.

On the way, driving fast, eating up the darkness, Miss Jardine said, ‘But I simply don’t understand the Gachets. If they knew you were coming today. I mean, it’s simply scandalous.’

‘They are decadent people,’ Yvonne said slowly. ‘They have been spoiled, pigging it in that house all winter. The owners take no interest, now their children are grown up. The Gachets did not wish to work for you, obviously.’

‘But at least they could have said—’

‘They are decadent people,’ Yvonne repeated. After half a mile, she added, ‘Gachet drinks two litres of wine a day. His wife is Italian.’

Now there were so many people. The hours of being alone were over. But she could not speak. She sat forward on the seat, her hands tightly clasped, her face shrivelled. When they came to the turning she opened her lips and took a breath, but Miss Jardine had already directed them. They lurched and bumped up the lane, screamed to a stop in front of the black barn doors.

‘Is that locked too?’ Yvonne asked.

There was no answer. They clambered out. Yvonne gave the tools and the rope to the men. Yvonne and Miss Jardine carried the blankets and the first-aid box. The moonlight turned the grass into lava.

‘A torch,’ Miss Jardine said. ‘Blast!’

‘We have a light,’ the interpreter said. ‘Although it does not seem necessary.’

‘Good. Then let’s go.’

She ran in front of them, although there was no purpose in reaching the house first. It was so clear in the moonlight that she could see the things spilled out of her handbag, the mirror of her powder compact, the brass catch of her purse. Before she was up the steps she began to call again, ‘Johnny? Johnny?’ The others, coming more slowly behind her with their burdens, felt pity, reluctance and dread.

‘What shall we try first? The door?’

‘No, we’ll have to break a window. The door’s too solid.’

‘Which of you can use an axe?’

The men glanced at each other. Finally the interpreter shrugged his shoulders and took the axe, weighing it. Yvonne spoke contemptuously to him, making as though to take the axe herself. He went up to the window, raised the axe and smashed it into the shutters. Glass and wood splintered. It had only needed one blow.

She was at the window, tugging at the jagged edges of the glass. The interpreter pushed her out of the way. He undid the catch of the window and stood back, examining a small scratch on his wrist and shaking his hand in the air as though to relieve some intolerable hurt. She was through the window, blundering across a room, while she heard Miss Jardine calling, ‘Open the front door if you can! Hold on! We’re coming!’

They did not exist for her any longer. She did not look for light switches. The stairs were brilliant.

‘Johnny?’ she called. ‘Johnny? Where are you?’

A door on the first-floor landing was wide open. She ran to the doorway and her hands, without any thought from herself, flew out and caught the lintel on either side, preventing her entrance.

He was lying on the floor. He was lying in exactly the same position in which he had curled on the grass outside, except that his thumb had fallen from his mouth; but it was still upright, still wet. His small snores came rhythmically, with a slight click at the end of each snore. Surrounding him was a confusion, a Christmas of toys. In his free hand he had been holding a wooden soldier; it was still propped inside the lax, curling fingers. She was aware, in a moment of absolute detachment, that the toys were very old; older, possibly than herself. Then she stopped thinking. She walked forward.

Kneeling, she touched him. He mumbled, but did not wake up. She shook him, quite gently. He opened his eyes directly on to her awful, hardly recognisable face. ‘I like the toys,’ he said. His thumb went back into his mouth. His eyelids sank. His free hand gripped the soldier, then loosened.

‘Jonathan!’

With one hand she pushed him upright. With the other, she hit him. She struck him so hard that her palm stung. One of the women started screaming, ‘Oh, no! . . . No!’

She struggled to her feet and pushed past the blurred obstructing figures in the doorway. She stumbled down the stairs. The child was crying. The dead house was full of sound. She flung herself into a room. ‘Oh, thank God,’ she whispered. ‘Oh, thank God . . .’ She crouched with her head on her knees, her arms wrapped round her own body, her body rocking with the pain of gratitude.

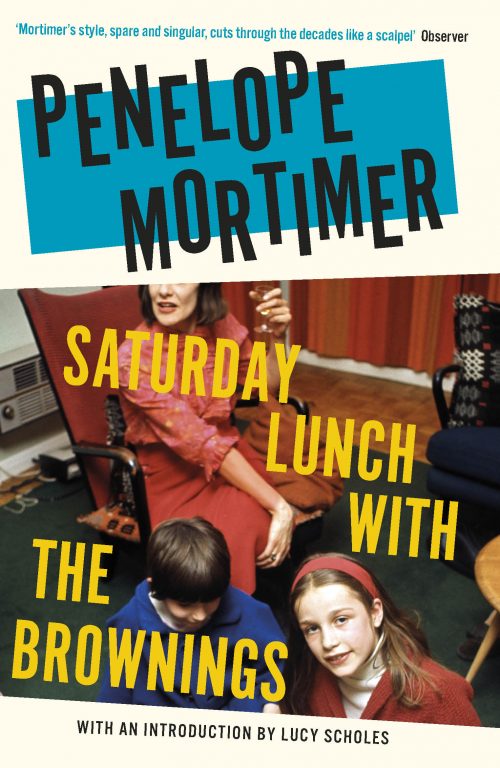

‘The Skylight’ is taken from Penelope Mortimer’s collection Saturday Lunch with the Brownings, out with Daunt Books.

Image © Peters Picture