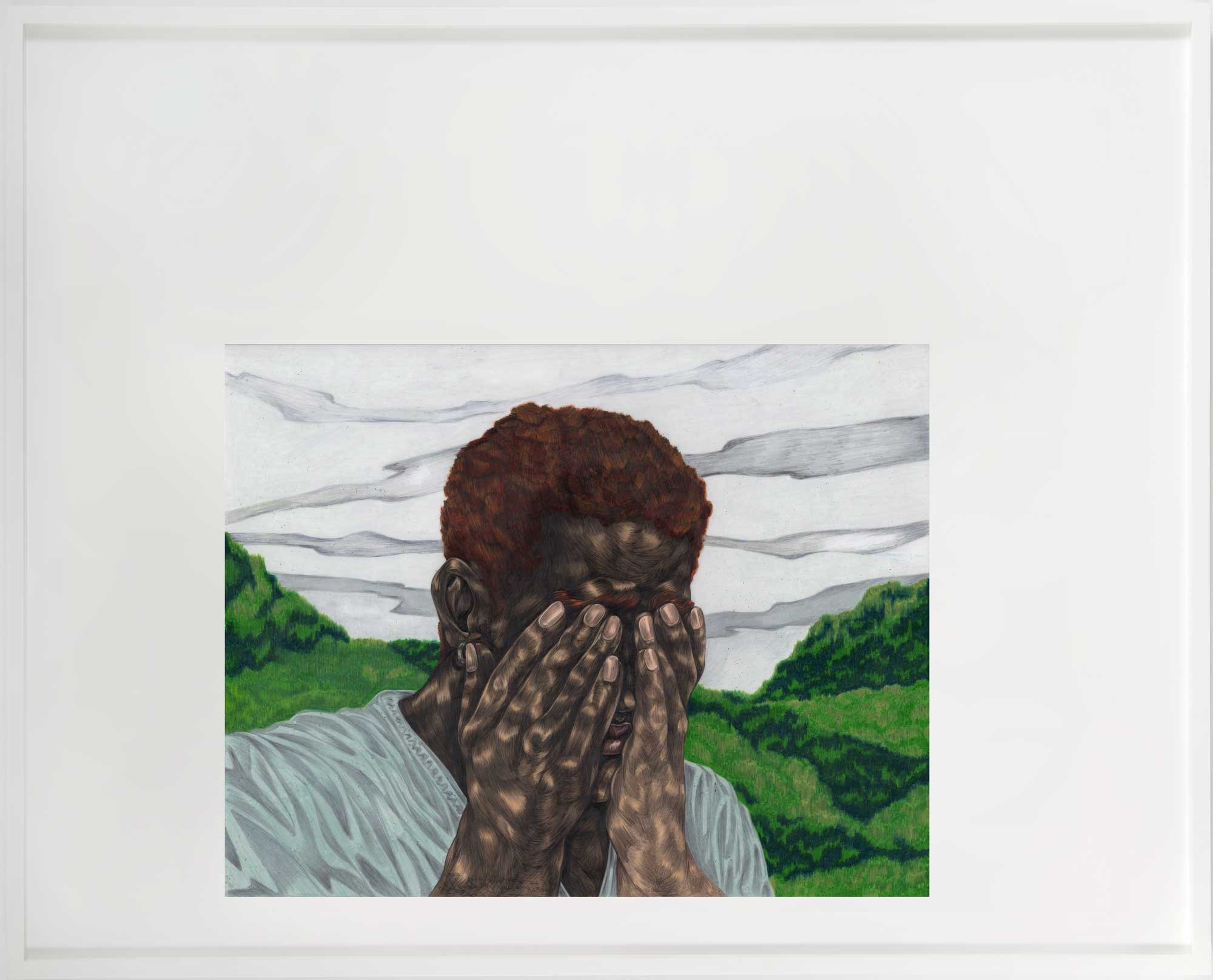

In the painting As He Watched Him Walk Away by Toyin Ojih Odutola, a man cups his head in his hands. We can’t see his eyes, just a bit of nose, a mouth in pout. We see the man, but his sorrow is obscured; we read it in the gesture, those cupped hands and sloping shoulders, that furrowed brow, and of course, the mouth. Is it truly pouting? We read the man’s sorrow, too, in the striking contrast between the gesture and the lush green landscape that surrounds him. How could one find oneself bereft there, in a place of such clear abundance? Who walked away, and when, and why? A story is emerging.

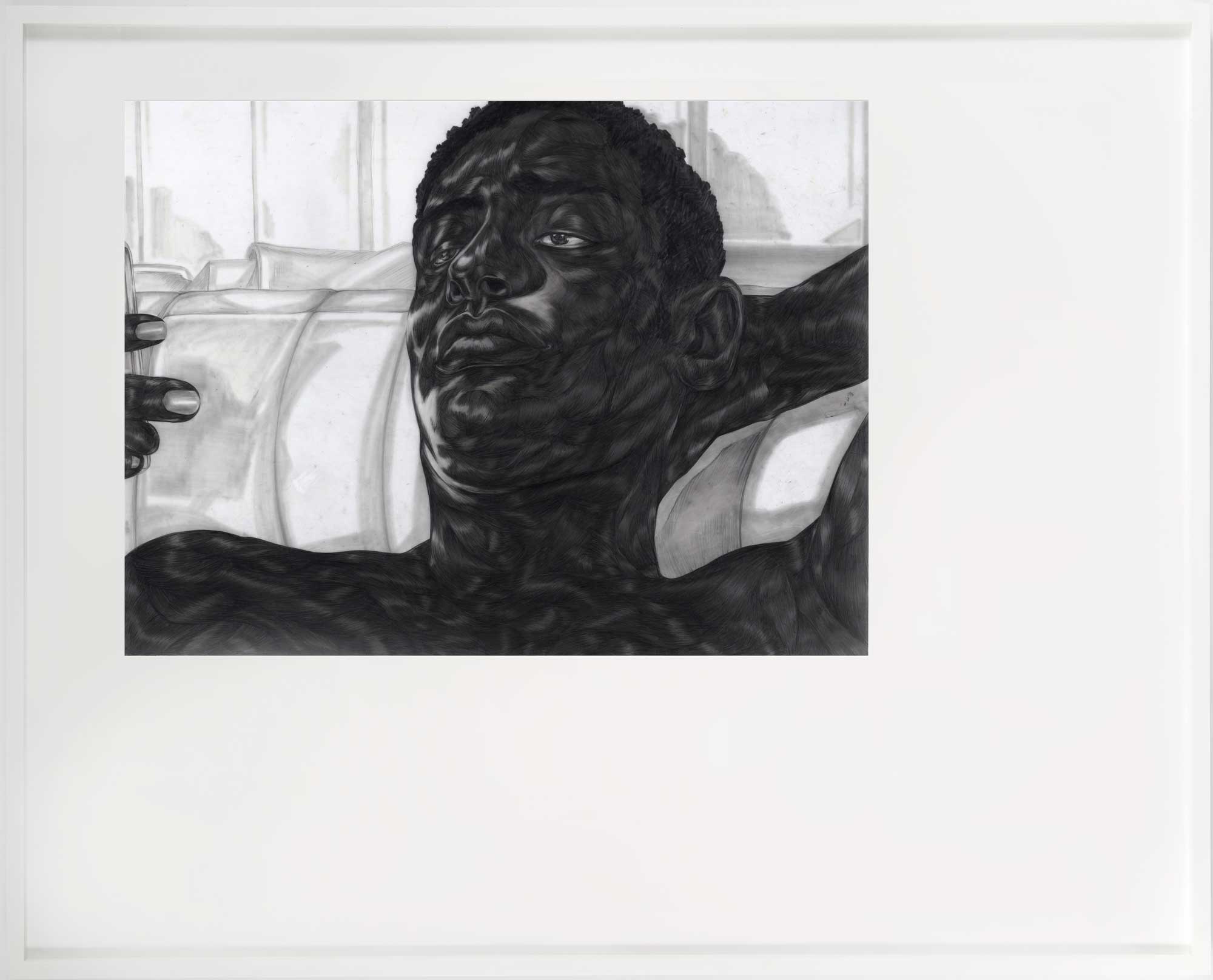

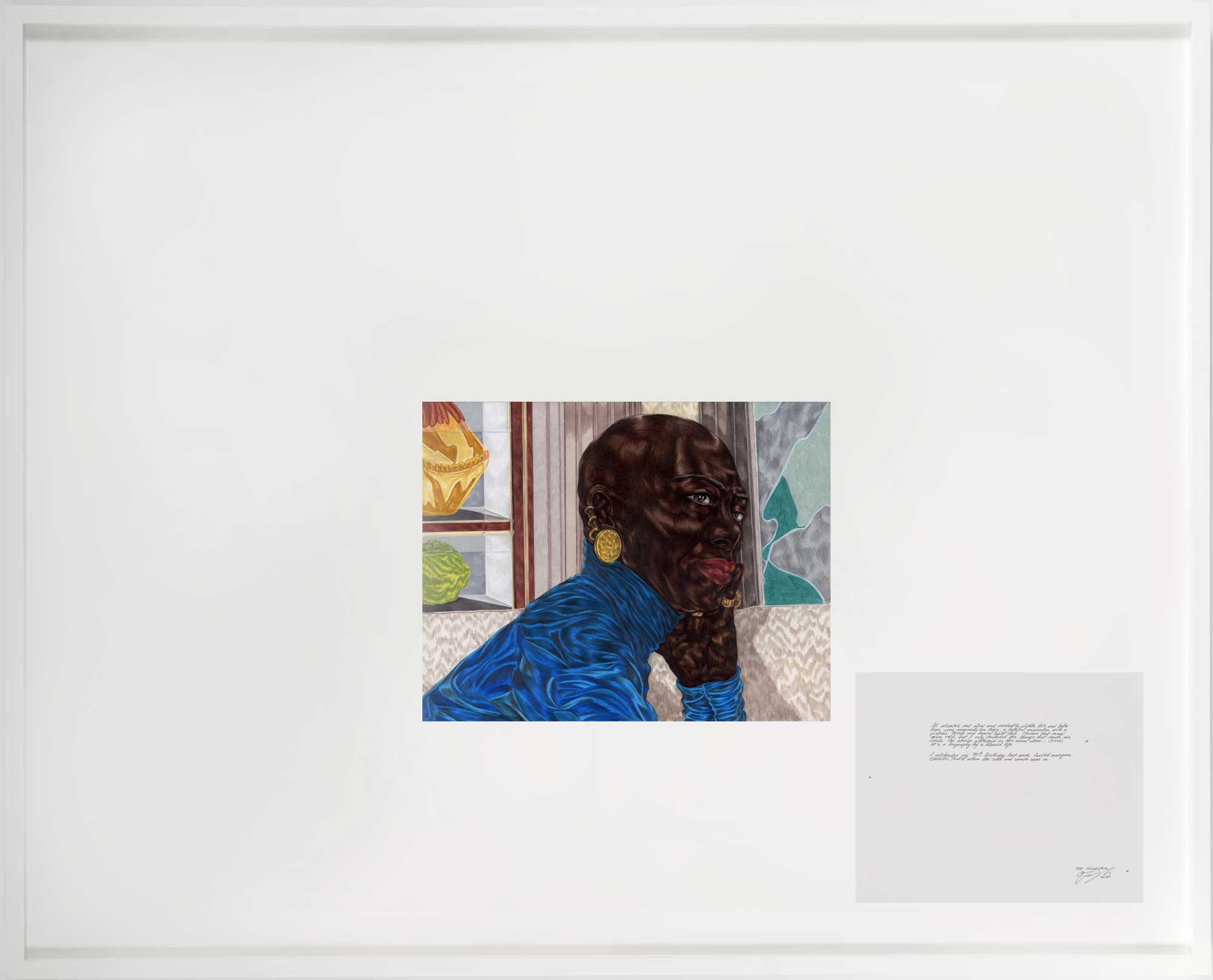

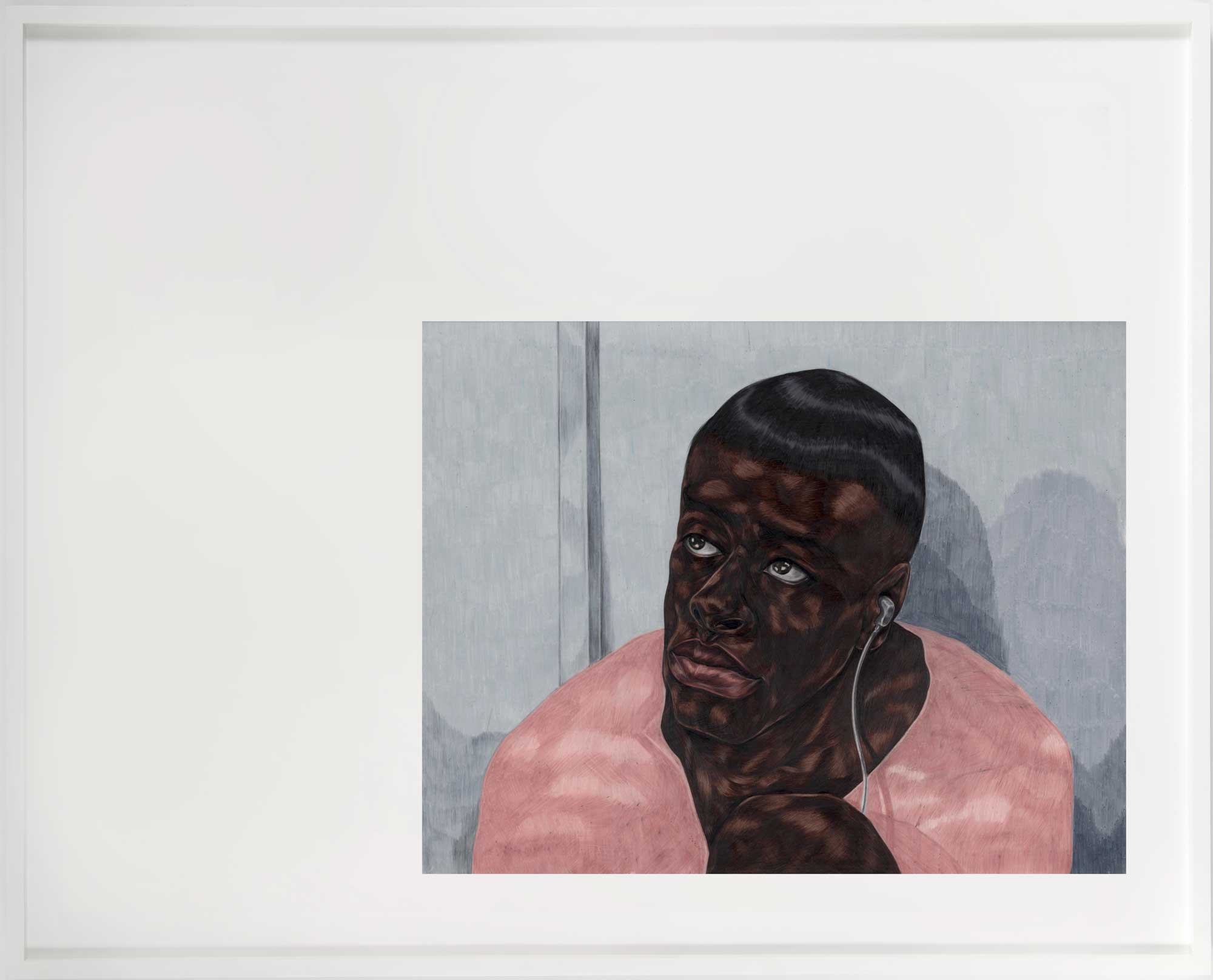

The drawing forms part of Toyin Ojih Odutola’s latest show at Jack Shainman Gallery – ‘Tell Me a Story, I Don’t Care If It’s True’. The collection is comprised mostly of images and texts that Ojih Odutola created while under lockdown in New York during the coronavirus pandemic, and, as the world is still in the midst of this pandemic, what was to be a gallery show will now be online.

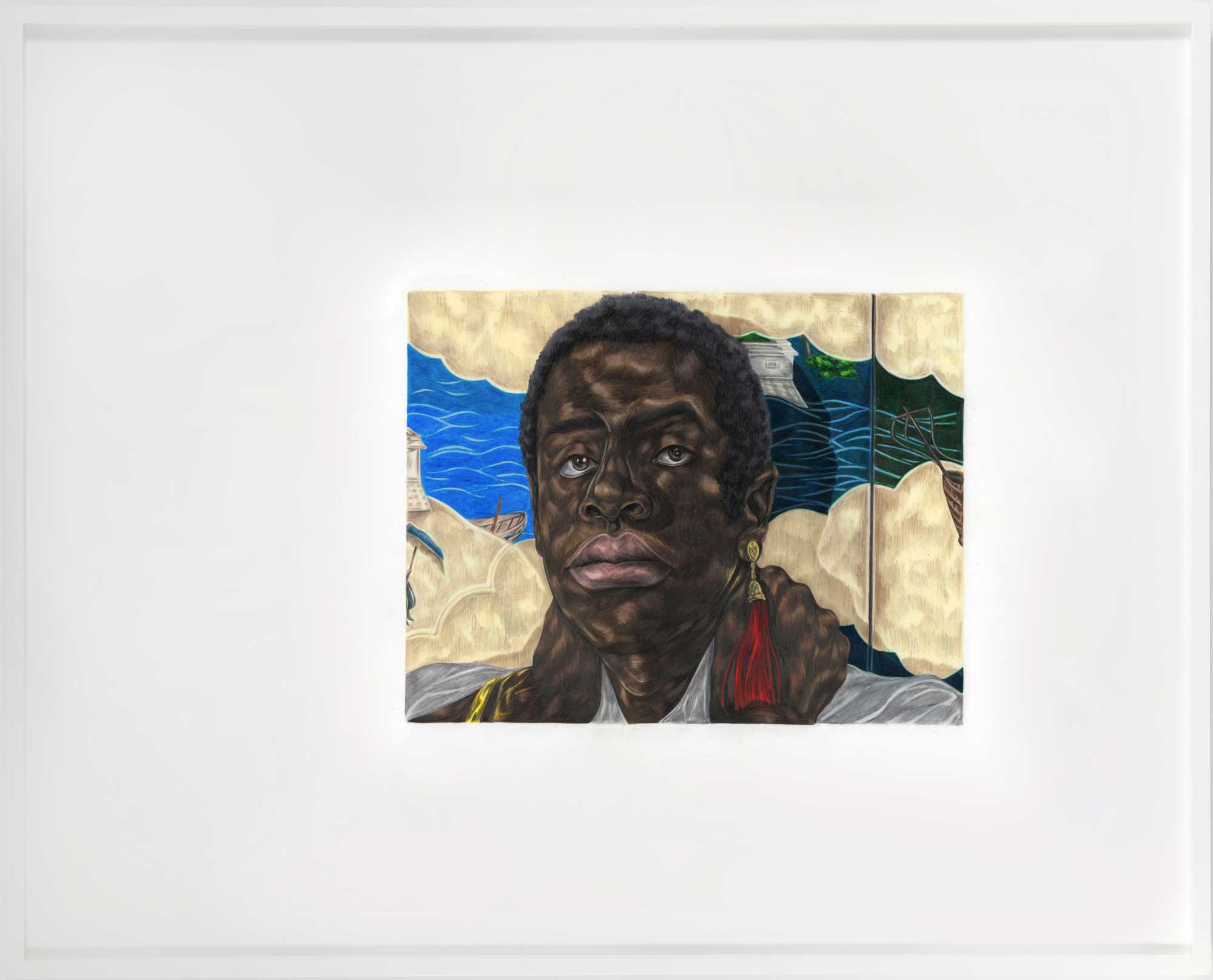

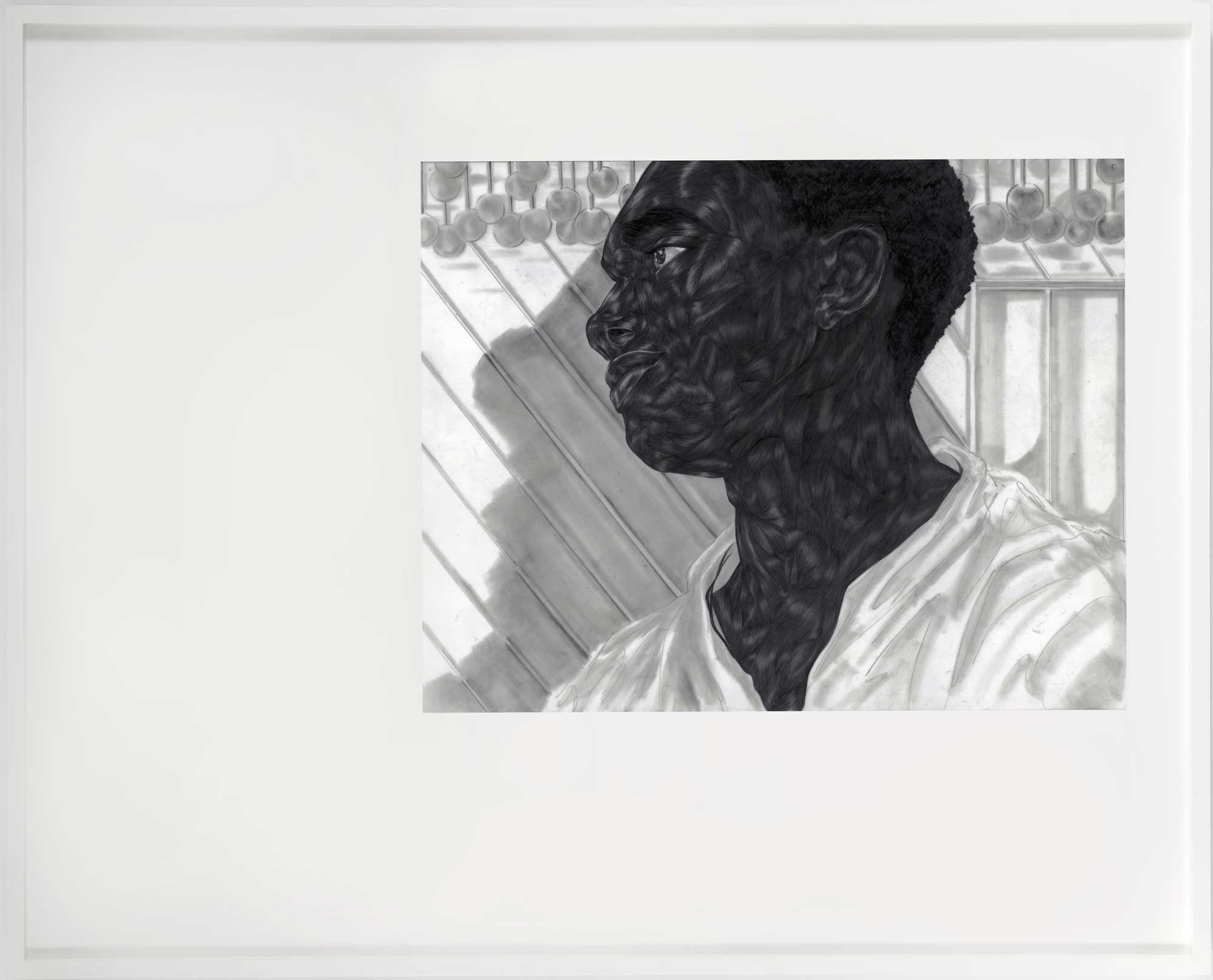

Ojih Odutola is interested in interpretations, the biases we bring to bear when we engage with an image, the unreliability of story. She knows that there is a distance between what the text tells us we are seeing and what we are actually seeing, and that meaning making happens, in part, through how we reconcile the images we see and the stories those images conjure. As she puts it, ‘I’m often fascinated with how miscommunications happen and what the imagination conjures in misconstrued spaces – the gulfs between what is intended and how it is received.’

These days, as America continues to roil in the wake of yet another series of extrajudicial murders of black people at the hands of white cops and vigilantes, murders that, in some cases, are known because they are seen: videoed, posted and shared, I am thinking all the more about the stories we tell ourselves about the images we see. The way that people time and again justify the murders based not on what they are actually viewing – men and women being shot, choked out, kneeled upon – but by the story they imagine the image is rendering: a hand reaching for a gun, a robbery taking place at some point in the future, thereby justifying the murders ex post facto. These images that we assume to be fixed, objective, reveal themselves as sites for story.

For years, I have actively avoided these videos, disturbed as I am by the terrible spectacle, the way that such accounts of brutality against black people, as Saidiya Hartman writes in Scenes of Subjection, ‘immure us to pain by virtue of their familiarity’. I’m incensed by essays like the one that called Darnella Frazier ‘the most influential filmmaker of the century’ as though the murder of George Floyd was a work of art. One of the things that makes Ojih Odutola’s work art – real, intentional, beautiful art – is the way that she toys with our biases, asks us to interrogate them. She draws images of black people understanding that the stories that have been told about us have often been negative and damaging, and her work, like the best works of speculative fiction, probes our understanding of the world and asks us to imagine a different one, a better one. What if Western colonialism and imperialism hadn’t ravaged the wealth and prosperity of countless African nations? What if our art had not been stolen, our people not enslaved? What if we imagined a good story, a righteous and just story, and then we worked to make it true?

Images courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. ‘Tell Me a Story, I Don’t Care If It’s True’ will now show at the gallery in September 2020.