Having disembarked, clown car-style, from two rented minivans, the twenty-three performers of ACT! Theatre for Kids begin their duckling march across the college quads. The line of child actors draws stares and hoots. They stop conversations. And Julie – the longest-serving (or longest-surviving, as Mr A likes to say) company member – feels a new shiver of embarrassment.

Other troupes here at the state theater conference move in loose agglomerations, with uniforms of sagging jeans, black T-shirts, and bandannas, sporting downy whiskers and ponytails. They joke and shout and curse and cavort. They smoke. Probably they even drink, on the sly. But not so the fifteen girls and eight boys of ACT!, who range in age from five to eighteen and are at all times lined up from tallest to shortest. Attired in pressed khaki pants (except for Julie, who wears a khaki ankle-length skirt), tucked-in T-shirts, and, tied around their waists in this ninety-five-degree heat, shiny red nylon jackets embossed across the back with the ACT! logo, they sing as they promenade – show tunes, vaudeville ditties – Julie’s voice the loudest and clearest of all. She has been belting out hymns with her Pentecostal church choir since she was six years old. She is now almost seventeen.

At the head of their line struts J. J. Abrusley, the beloved, the indulgent, the scornful ‘Mr A,’ their gallant captain, their pied piper, small and dapper, straight-backed and trim, extending an arm left or right to steer his trusty procession. His head swivels on a tiny neck, mounted on shoulders made straighter and wider by the stiff pads in his sport coat. Sometimes he turns around to face his charges, his backward stride graceful and confident. In a voice as pinched and reedy as a kazoo, he calls out marching songs. Five bodies ahead of Julie, Jabowen, seventeen and tall and slim, with a bouncing, joyous gait, leads the line of kids. At the rear, Mr A’s mother, Mother A, designated chaperone for the girls, rifles through her enormous purse for tissues, lotion, the crumpled campus map.

All of this – the lockstep marching, the matching clothes, the raising of hands to speak – seemed reasonable back at the rehearsal space this morning, no doubt a necessity for an undertaking such as this, the first of several long-weekend jaunts, the brave inception of a summer tour across the state of Louisiana. When they assembled this morning in the parking lot of the shopping plaza in Lake Charles, where ACT! has a storefront between a ladies’ fashion outlet and J. J.’s Food Mart (owned and operated by Mr A’s parents and named, long ago, for the infant Mr A), they felt every bit like soldiers off to a righteous war. Mr A moved down the line of kids, addressing each in turn with a gentle clasp of a shoulder or elbow. He looked every kid in the eyes, called each one, warmly, babe. Meanwhile Mother A, in her meticulously fluffed silver bouffant and purple tracksuit, ticked off names on a roster and collected permission slips.

This is a new development, this touring business, an expansion of the little company, which until now was limited to a rented auditorium in an abandoned, dilapidated school or to guerrilla-style productions at the mall. But they made a bit of a name for themselves last fall doing whistle-stop campaign performances for now-Governor (again) Edwin Edwards, and with political connections and a new influx of tuition funds, they are taking this show on the road.

This first trip includes the conference in Lafayette and then a New Orleans water park, where they will perform their repertoire of show tunes and Shakespeare for the dripping, shouting, lemonade-sucking hordes loosed from school. Because Julie has been around the longest, she takes charge of practical details like loading luggage and keeping five-year-olds in check. But she didn’t sign up to be Mr A’s assistant, and it’s been wearing thin.

More than that, while she was loading duffels into the van this morning, she overheard two of the mothers in the parking lot.

‘J. J. always picks a favorite,’ said one.

The other one laughed, and something in that laugh, or maybe just the fact of it, rankled Julie.

Now they are waiting along the wall outside the college auditorium where they will soon perform their Shakespeare montage. Everyone, even the smallest kid, has a bit. There are very short fragments from The Tempest, Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and the sonnets, a smattering of just about everything, with some basic facts about the Bard thrown in, less to provide context than to give the youngest children something easy to say. The centerpiece is the strangulation scene from Act V, Scene 2, of Othello, with Jabowen as Othello to Julie’s Desdemona. Jabowen is the first and only black boy ever to join the company, and Mr A has seized upon the opportunity.

At the front of the line, Jabowen and Mr A are talking. Or, more than talking, really. Julie has noticed this before – it’s impossible to miss – but today it worries her more deeply than she can quite admit. Jabowen and Mr A bend toward each other, Mr A’s hand cupping the back of Jabowen’s neck, Jabowen’s head angled down to Mr A’s, their foreheads nearly touching, eyes locked. Mr A’s feet do an abbreviated box step and his hips shift this way and that while Jabowen stands perfectly still. It is fascinating to watch them, though it ignites a complicated pilot light of jealousy in Julie. What is happening between them is very strange but also nearly beautiful.

Under an oak tree nearby, some teenagers in ripped-up jeans and flannels have been smoking hand-rolled cigarettes and running lines too loudly. ‘What the fuck!’ one is shouting. ‘What bus did you get off of, we’re here to fucking sell. Fuck marshaling the leads. What the fuck talk is that?’

The little kids down the line look nervously at one another and then at Julie, who shares their anxiety but says, ‘Don’t listen. Just ignore them.’ Julie, who, no matter the context, will cringe from her high-spirited peers as from a nest of vipers, wishes she wasn’t fearful, but having spent so little time in the world outside her Pentecostal congregation, she knows that she cannot tell vipers from squirrels, danger from fun. And what frightens her more than the danger itself is her own incapacity to see it.

A middle-schooler tells a younger kid, ‘I don’t think those are regular cigarettes.’ Up near the front of the line, Monique, a sixteen-year-old with permed hair, a raspy voice, and a wild energy that intimidates Julie, stuffs her fist between her teeth and shudders with stifled mirth. Under the tree, the teenagers pause in their rehearsal and gawk back at the trail of scandalized kids and the man and boy at the head of the line in their wonderful and disquieting private dance. Mr A and Jabowen, in each other’s thrall, notice none of this.

When, a moment later, the eight-year-old Blaine wanders dreamily out of line to examine a dead pigeon that rests, with its neck twisted, in the grass, Mr A breaks away from Jabowen and rushes over to scare the wayward boy back into place.

Jabowen approaches Julie and takes hold of her elbow. ‘Mr A wants us to run Out, strumpet,’ he says. He tugs her gently away from the wall. All heads turn to watch.

Jabowen is distracted and will not look her in the eye. It was difficult to get him to commit to the smothering. In the first rehearsals he would bellow, It is too late, and palm Julie’s face like he was closing the lid of a Tupperware. Finally they decided strangulation would be easier than smothering, which seemed to require a pillow, and Jabowen would come at her neck, his narrow palms and long fingers opening like a Venus flytrap. She grew intimately acquainted with his hands, which were warm and papery, tactful. He would administer the strangling as deliberately and gently as a doctor, pressing his fingers to her collarbone and tensing the muscles in his arms. Julie would take hold of his slender wrists and thrash, desperate-seeming but controlled.

Now they square off like wrestlers and drop their heads, a deep pause and self-collection, a summoning of the essences of Othello and Desdemona. Jabowen counts down from three. Their eyes meet. In Jabowen’s, there is an angry flash, a ferocity. He steps forward and again grabs Julie’s elbow, violently this time. She shrinks from him first and then falls upon his chest. His free hand burrows into her mass of hair, yanks a handful, pulls hard so her face tilts to his. She has worked up some tears, though mostly it’s the pain in her scalp that brings them on.

‘Out, strumpet! weep’st thou for him to my face?’ Jabowen sighs. He tips his head back and lowers his eyelids, like a jeweler appraising a stone.

‘O, banish me, my lord, but kill me not!’

‘Down, strumpet!’

‘Kill me to-morrow, let me live to-night!’

‘Nay, an’ you strive – ’

Their faces are so close they are sharing breath, and, for Julie, they are together again in the costume closet, that day last month, when, in the fusty, close quarters, amid the reek of stale sweat and old shoes, they could not keep themselves from one awkward and somehow belligerent kiss, Julie’s first.

She frees herself from his insistent hands. ‘But half an hour!’ she says.

‘Being done, there is no pause.’

‘But while I say one prayer!’

‘It is too late.’ He pounces upon her.

She thrashes and hisses, ‘O Lord, Lord, Lord!’

And it is done. She goes limp in his arms. Applause breaks out in the line, the other children nodding.

‘Again!’ Mr A shouts.

When they finally take the stage for their performance, there is tittering in the audience, some merciful shushing, but when it is done, when Desdemona has expired, there is unreadable silence. Julie pulls away from Jabowen and blinks into the darkness beyond the stage. A kid rises in the third row. He whoops and claps and whoops again. The girl next to him laughs and tugs at his shirt tail, but then another kid stands, and a few more here and there, then the whole audience is up, clapping and whooping. The little kids in the company join Julie and Jabowen onstage, where they wave, curtsy, and blow kisses. This is what they’ve been taught to do. They can’t hear the mockery in all the applause, but Julie’s face heats up.

Jabowen’s warm, dry hand finds Julie’s; he laces his fingers with hers and squeezes, continues to squeeze, leans into her ear and says, ‘Philistines.’ He sweeps their arms up and pulls Julie down with him into a deep and generous bow.

At the first motel, and at each motel thereafter, Mr A has made reservations for only two rooms, one for the boys and one for the girls. They are on a tight budget, after all. While Julie, Jabowen, and Mother A hustle the kids and their duffels and sleeping bags from van to room, Mr A creates a diversion at the front desk, asking for directions to elaborately out-of-the-way landmarks and pretending confusion at every step until all the clerks have gathered around to argue among themselves. Thus the covey of children passes unnoticed into their overfull quarters.

In the girls’ room, Julie faces the strategic problem of sleeping space for sixteen bodies. Mother A is no help at all; when it becomes clear that her spatial awareness is entirely distorted, that in each instance little girls are much bigger and areas much smaller than she estimates them to be, Mother A retreats to the bathroom, refusing to help in the one way she possibly could – by asking her son to please, oh please, for heaven’s sake, reserve another room.

No matter how Julie configures the space, there is always one girl left with nowhere to sleep. In what seems the best possible arrangement, she and Mother A will share one bed with the tiniest girl, and four small- to medium-sized girls will share the other. The rest are assigned to every bit of floor space, including the entryway, a fire hazard to be sure. But what to do with number sixteen? The tub is considered, and the bathroom floor. Finally, Monique suggests that moving the little table and chairs to the boys’ room would free up just enough space. Julie takes up the table, and Monique picks up the chairs.

The boys’ room is bigger, Julie notices as soon as she enters – longer by at least four feet, wider by perhaps a foot or two. The beds are luxurious queens instead of fulls. Duffels and sleeping bags are piled in a tidy pyramid against one wall. On the table is a stack of board games: Life, Scrabble, Sorry!, Clue.

Six boys sit cross-legged on the floor in an orderly row, and the boy who has opened the door for Julie and Monique returns to his place on the end. They are playing some sort of word game, nickering like dolphins at Mr A, who perches on the edge of the bed, Jabowen at his side. ‘Baboon but not monkey,’ says Mr A. ‘Warrior but not chief.’

Julie peeks over the rim of the tabletop she is clutching to her body and waits for Mr A to give the girls his attention. Monique is not so patient. She bumps one of the chairs intentionally against the wall before she sets it down, then clears her throat.

‘Jules!’ says Mr A, cheery. ‘What do you need, babe?’

Without hesitation, Monique, a hand on her defiantly cocked hip, answers first, explaining their predicament.

Mr A orders two of the older boys – not Jabowen – to stack the table and chairs out of the way, in the corner of the room, and when they have done so and have resumed their places on the floor, he pats the bed next to him and tells the girls, ‘Stay a minute. See if you can figure this out.’

Although Monique is fast and lithe and more ruthless, Julie, a couple of steps closer to the bed, has the advantage of proximity and nabs the place at Mr A’s left hand, which means Monique must join the boys on the floor.

Without explanation, Mr A continues the game. ‘Actresses but not actors. Othello but not Iago.’

Blaine raises his hand. ‘Black but not white?’ ‘

Nope, wrong again,’ Mr A says.

Julie is too close to him to watch his face, which has grown an uncharacteristic stubble that extends down his neck, where the skin is red and bumpy. Instead she looks at his lap and, just on the other side of his lap, Jabowen’s. Mr A’s legs, thin as pipes, are crossed at the thighs, his hands resting, one atop the other, on the uppermost knee. The suspended foot bounces restlessly, making the bedsprings squeak. Jabowen sits with his legs spread wide and reclines slightly, propped on his arms.

‘Swimming but not drowning,’ Mr A says.

Monique shoots her hand up and says, ‘Does it have something to do with . . .?’ But she trails off.

‘Oh!’ Jabowen says. ‘I’ve got it! William but not Shakespeare.’

‘Yes!’ Mr A says. His right hand reaches for Jabowen’s left leg and pats it on the thigh. ‘Exactly!’

‘Appendicitis but not cancer!’ Jabowen says.

Mr A’s hand comes to rest – frankly, firmly – just above Jabowen’s knee.

Monique tries again. ‘Sick but not dead?’

‘No, that’s not it,’ Mr A says, and the hand on Jabowen’s thigh gives a little squeeze, then retracts, as if Mr A has remembered himself.

They go on like this for a while, the boys and Monique offering wrong answers, Mr A throwing out new examples. Sometimes Jabowen chimes in, and when he does, Mr A’s hand reaches over, comes alive with friendly patting.

‘Any ideas, Jules?’ Mr A says.

She feels him looking at her, but she cannot stop watching the hand. Over the hill of Mr A’s crossed knees, Monique is peeping at Julie with one eyebrow theatrically raised and her glossy upper lip in a curl. Julie meets Mr A’s eyes. They are, as always, shockingly blue, direct and perceptive. Jabowen drops flat onto the bed and lolls his head to look at her behind Mr A. He gives her a warm, flirtatious smile. He seems quite pleased with himself, actually.

‘What are the rules?’ Julie says to Jabowen. And then to Mr A: ‘I don’t understand the rules.’

If Julie’s parents knew the iniquities to which the theater has tempted their daughter – for instance, changing out of her pious to-the-ankle denim skirt and into a pair of knee-length shorts on arrival at rehearsals, or being made by Mr A to die again and again at the hands of a boy, a black boy no less, with each little death arousing concupiscence – they would have removed her from ACT! long ago. But they stay far away from ACT! Never in her five years with Mr A have Julie’s parents seen her perform. For them the public display of her talent is confined to church services, where she sings hymns beautifully, with great drama even, but only for God’s glory. Outside of church, performance is, if not strictly forbidden, a temptation – to lust, to pride.

But so complete was the trust Julie’s parents had in their daughter, so good and smart and sensible a girl was she, and so flattered were they in spite of themselves that their girl at only twelve was cast in the lead of a play on her very first try, that they gave in after some pleading and a promise that Julie’s involvement with ACT! and Mr A was to remain a secret from their Pentecostal congregation with the same urgency as a pregnancy begotten out of wedlock.

There had been some trouble with her grandmother, though. On the night before Julie’s first performance, the family was seated around the table offering up the dinnertime prayer when MeeMom raised herself out of her chair. She held her hands out to Julie, palms open, then let them rise slowly upward as though she were testing for rain. ‘My baby,’ she said. ‘My baby, Julie.’ She was waiting for the prayer to come, pleading with her granddaughter and with God, and then the prayer did come. ‘The Lord God has given you to us, Julie, He has laid you on my bosom like a sleeping babe, and I ask Him to help me protect you.’ She came around the table and pulled Julie toward her soft belly, held her there for a while and stroked her hair, tucked strands of it behind her ears, petted her face. Julie’s father and mother kept their eyes on their forks. MeeMom pressed her hands to either side of Julie’s head, muffling her ears, and said, very quietly, ‘I ask you, Jesus, to cleanse my Julie in Your blood. Wash her clean in Your blood, the blood of Jesus Christ. Release her from the devils within her. Fill her to overflowing with the gift of the Holy Ghost, let it fill her.’

And the prayer, a muted buzz in Julie’s ears, vibrated, escalated, then left language behind. The tongues of angels overtook the deficient tongue of man, and the pulsing through the hands of her grandmother – her own beloved MeeMom, who had taught her and loved her and always been kind – the seeming pulse of grace itself, awakened something angry and latent in Julie’s chest, a demon, maybe, hammering to get out.

The next day she went early to rehearsal and told Mr A, weeping, that she had to quit. For her grandmother, whom she loved, she had to quit.

He stood from behind his desk, planted his hands presidentially upon it, and leaned forward, his sport coat spreading out from his small frame like the agitated frills of a lizard. ‘That’s exactly why I don’t go in for all that Holy Spirit gobbledy-gobble,’ he said. ‘These are the same people who would burn every volume of Shakespeare if they got the chance. Philistines, Julie! These people are philistines.’ He ringed an arm around her shoulders as they walked down the hall to the rehearsal room and, drawing her close, said in her ear, to the jittery, jumping thing that her grandmother could not cast out: ‘Mr A is telling you, and what Mr A tells you, you can believe: You. Are. No. Demon.’

That day in rehearsal, when Mr A, leading the chorus of nonsense phrases that would unravel their tongues for performance, raised his hands to heaven, clapped them over his head, and whooped like a zealot – ‘Canada Molega Rimini Brindisi! Canada Molega Rimini Brindisi! Nagasakiiiiiiiii! Hallelujah! Praise the Lord Jesus!’ – Julie, like the others, laughed and answered the call.

Back in the girls’ bathroom, Julie crouches on the lid of the toilet with a stopwatch in hand. Each girl has two minutes for a shower. Julie gives a warning at one minute and another with thirty seconds remaining. At two minutes, if the curtain has not been shoved aside and a naked body toweled off and wrapped up of its own accord, Julie threatens, then pulls the curtain open herself, shuts off the water, and drags an occasionally still soapy and trembling little girl onto a soaking rug to towel and wrap her herself. Outside, Mother A presents each one with her neatly folded panties and pajamas. They must all be clean and ready for bed by nine. Thus spake Mr A.

For herself, Julie will reserve the luxury of a morning shower, before the other girls are up, when she can sufficiently lather, rinse, and coil into a bun the thick mane of hair that hangs past her waist, and see to certain aspects of feminine hygiene that simply cannot be addressed, along with everything else, in two minutes. Under the cover of predawn darkness, her hypocrisy will go mostly unnoticed.

It is awkward, she knows, to claim this privilege when a few of the other girls, also in their mid- to late teens, have the need but no recourse. Monique, though, pushes past the two-minute mark every time. While Julie, sweating, wipes steam away from the face of the stopwatch, Monique says, ‘What’s the deal, do you think, with Jabowen and Mr A?’

‘One minute left,’ Julie says.

The rush of water changes tone and there’s a sudden spatter against the curtain. Julie wipes the damp from her face with a piece of toilet paper, which, when she drops it into the trash, is smeared with creamy brown makeup – another taboo, like shorts and dancing, in her family home.

‘It’s starting to give me the creeps,’ says Monique.

‘Thirty seconds.’

‘This whole thing, actually. Doesn’t it feel sometimes like a. Like we’re in a.’

‘Fifteen seconds.’

‘Like a cult?’ The curtain moves aside a little and a furtive foot emerges, mounts the rim of the tub. Julie thinks Monique is going to give her a break and exit the shower without being told, but instead she reaches out with a dripping hand and roots around in the cosmetics bag on the counter until she finds a razor.

Julie inspects the watch. Time’s up. More than up. She gives Monique another minute, and at the end of that minute Monique is still shaving, so Julie gives her one more, two. Even three. ‘It’s been two minutes,’ she says, finally. ‘You have to get out.’

‘Oh, please,’ Monique says and does not get out.

At one in the morning, Julie is still awake. Mother A, herself equipped with earplugs, is snoring, deeply, strangely, loudly, on the other side of Julie’s bed. The little five-year-old is curled up like a bean against Julie’s back, drawing closer and closer with every hour and pushing Julie farther toward the edge. The room is too warm, heavy with a damp, swampy odor. The buzzing of so many bodies in sleep is its own kind of chaos, a swelling of potential energy, a spring stretched to its limit.

At 1.15 there is a knock on the door – a light, shy tapping with the tips of fingers, one, two, three. At first Julie thinks she has imagined this, or that the sound has come from somewhere inside the throbbing room. But then, a moment later, there it is again, a little louder this time. Julie swings her feet to the floor and barely misses Monique’s sprawled arm. She picks her way around bodies, testing each step with her toes before planting her foot. There is a third knock just as she reaches the door.

It is Blaine. He looks frightened. ‘I need to pee,’ he says, and grabs at the flannel crotch of his pajama pants. He casts an anxious glance over his shoulder, as though he expects to have been followed, and does a little dance. ‘I need to pee.’

‘What’s wrong with the toilet in your room?’

‘Mr A is in there.’

‘Did you knock?’

‘He said go away.’

‘Good grief, Blaine. If he catches you in the hallway, you’ll be in serious trouble.’

‘He’s been in there forever.’ Blaine bends into a crouch, then stands and again checks behind him for pursuers. ‘Jabowen is in there too,’ he says. ‘I mean, I think he is. He’s not in bed.’

‘Maybe he took a walk or something. Maybe he went to get ice. Or a snack.’

‘Julie, please can I pee?’

What else can she do but let him in? She doesn’t follow him, though. Instead she goes to the door of the boys’ room and finds it propped open with a sneaker. She pushes it open just enough to poke her head through. A sliver of light spills out under the bathroom door, only a couple of steps from the hallway. Julie slips inside the room and presses her ear against the bathroom door.

There is low talking with long, pensive pauses. She can’t make out the words, but she recognizes their tones and textures, their deep, serious hum. It is indeed Jabowen and Mr A. When the door to the room swings open behind her, she starts and nearly cries out. It is only Blaine. They squeeze past each other – she to the hallway, he to bed – averting their eyes.

At breakfast, Jabowen looks ragged in a nonspecific way, his eyes puffy and blank, preoccupied with the heap of pancakes and the halved egg burrito he is sharing with Mr A. The boys have all been served and are seated at a long bank of two-person tables, but the girls are still trickling through the line, confounding the clerks with elaborate orders and last-minute corrections.

Julie, who was wide awake when her alarm went off at six and feels as though she’s spent the night in the trunk of a rotted-out tree, has been standing at the counter, helping the little ones with their cash, matching receipts to trays, so hungry that she’s light-headed. She’s keeping an eye on the open chair at Mr A’s table, and as each girl goes off to find a seat, her head floods with a desperate rush of blood. There is an answer at that table to the question of the closed bathroom door; there will be signs, and if she doesn’t get to that table soon she will be excluded irreversibly from whatever is happening between Jabowen and Mr A. Meanwhile she mixes up orders, she miscounts bills.

When Monique, the last in line, reaches the counter, she says, ‘Julie, you’re purple!’ She orders a breakfast sandwich, pancakes, hash browns, an extra side of bacon, and a vanilla shake. ‘God, I’m starving,’ she says.

If none of the other girls has the gumption to claim the seat across from Mr A, deterred by an instinctive and inviolable sense of the troupe’s pecking order, Monique certainly does. And in fact, Julie, now so flustered that she orders nothing but coffee and a biscuit, stares after Monique as she flounces down the aisle directly to Mr A’s table and claims the empty chair as hers, exactly as she did in the high school cafeteria on her first day as a freshman, certain of her place at a table full of cheerleaders and dancers, while Julie, a junior, had been unable in two years to establish herself except in a lonesome corner with kids from her church, better dressed for the prairie than for adolescence. The two girls had known each other from ACT! for a while by then, but when Monique saw Julie in her trailing skirt and grandmotherly bun, she puckered her lips in a smirk and moved on.

Now, though, when Julie finally has her tray in hand, with her sad little breakfast that she doesn’t even want, the coveted seat is still empty. Mr A is waving her over, having shooed Monique to another table.

Jabowen peels back the aluminum lid of an orange juice, concentrating, as careful in this as he is with Desdemona’s neck. Just when Julie has decided that he is, for one reason or another, avoiding her eyes, he looks up, twinkle-eyed, grinning. ‘Straws are for philistines,’ he says, and takes a deep gulp.

Mr A swipes a forkful of pancakes off Jabowen’s plate and onto Julie’s. ‘You don’t have nearly enough to eat there,’ he says.

Julie says she’s not really hungry. She picks up her biscuit and nibbles it, but feels like she’ll gag if she tries to swallow. She lifts her napkin to her mouth and discreetly spits the biscuit out.

‘Got to keep your strength up, babe,’ Mr A says. He takes hold of the nape of her neck and gives it a quick little one-handed massage.

‘Today’s your big New Orleans debut.’

For the rest of breakfast, they are all business. They discuss the lineup of songs and skits for their performance later that day – on an outdoor stage at the water park – and Mr A makes a list on a napkin, which he entrusts to Julie. He calls Mother A to their table and confers with her over directions to the water park and the motel.

When the other kids, high on syrup and surreptitiously ordered soft drinks, get a little raucous, Mr A beats his keys on the table and growls, ‘Excuse me! Where do you think you are?’

Jabowen and Julie sit at attention, waiting for the next command. In other words, everyone behaves in a way that is exactly normal and Julie begins to doubt what she has seen, or, rather, begins to acknowledge her imperfect understanding of it.

At the end of the meal, Mr A and Mother A conduct one group to the bathrooms, leaving Julie and Jabowen in charge of the others, still seated and restless. Julie is flattening and crumpling, flattening and crumpling the discarded wrapper of a straw, and Jabowen is gazing out the window at the bright, hot day and the trucks trundling by on the interstate. Suddenly, he reaches across the table and stops her hands. He takes away the straw wrapper, balls it up, and lobs it into Monique’s frizzed-up hair. Monique is drawing something on a napkin for a small crowd of kids and doesn’t notice.

‘Why are you acting so weird?’ he asks Julie.

‘I’m not acting weird. Why are you acting weird?’

‘I’m not.’ His eyes get the ferocious gleam again. He looks over his shoulder toward the bathroom, she assumes for Mr A, and she tugs a napkin from their decimated serving trays and starts ripping it carefully to shreds.

After their kiss in the costume closet, Julie and Jabowen contrived to see each other outside rehearsal. Julie, wearing her best church skirt, told her parents she was needed at ACT!, and Jabowen picked her up from school in his car.

‘You drive a Mercedes?’ she said. It was a little nicked up and had so much trash on the passenger’s seat and floorboard – discarded T-shirts, crushed soda cans, crumpled and foot-printed essays, tests, and newspapers – that he had to shovel armloads into the back seat before he would let her in, but it was a Mercedes nonetheless.

‘Sorry,’ he kept saying.

‘I’m a slob. Sorry.’

‘Is this your dad’s car?’

‘Used to be. He’s sporting an S-Class now.’

He drove her across town to a neighborhood she had heard about but never visited, regarded as it was by her parents and grandmother with such pious contempt and suspicion (and some latent awe, sure) that it glowed in a radioactive nimbus of taboo. Here the grand houses of local celebrities – a television newscaster, a restaurateur, the mayor – lined the nicest stretch of lakefront in town. The petrochemical plants where her father worked were so far away that they were just a low, craggy shadow, hardly visible across the water. Jabowen slowed in front of a massive white mansion set too close to the road, crammed onto a piece of property just wider than the house itself. It loomed above them like the face of a cliff.

‘Isn’t this wild?’ he said. ‘It’s an exact replica of Tara.’

Julie stared at him, her face blank.

‘The plantation house?’ he said. ‘From Gone with the Wind?’

‘I haven’t seen that movie.’

‘You haven’t?’ He was disproportionately incredulous. ‘You have to see it. Ask Mr A. He’ll tell you how great it is.’ Then he turned into the driveway. ‘Real estate is so cheap in Lake Charles, it’s unbelievable. And anyway, my dad thinks it’s hilarious.’

‘Why?’ Julie said.

‘It’s kind of sweet, I guess, but you really have no sense of irony.’

Inside, Jabowen took Julie’s hand to lead her across a cavernous foyer, up a spiral staircase, down a hallway as long as a small hotel’s – and with as many closed doors – and finally into his room, which, unlike his car, was neat as a pin and smelled like sandalwood and pickles.

‘My parents aren’t here,’ he said. ‘We have the whole house.’

He showed her the things in his room that mattered to him: a trophy for dramatic interp, a funny birthday card from Mr A, a carved wooden mask that he got on a trip to Nigeria with his father. On his bedside table was a photo of him and his parents, the three of them draped in bright African prints. They posed in front of two thatch-roofed huts, all smiles, with a crowd of villagers lined up behind them, gazing frankly at the camera. His mother’s head was wrapped elaborately in some kind of scarf.

‘Is this where your parents are from?’

He gave a petulant little huff and said that Nigeria had been a business trip. His dad, who was a bigwig at CITGO, was from right here in Lake Charles. His mom, a high school math teacher, was from D.C.

Jabowen sat down on the bed next to Julie. ‘You have little hairs on your cheek,’ he said and brushed his fingers over them. He leaned in and touched her ear with his nose, then with his tongue.

She jerked away at first, but then she let him, and liked it. By the time the shadows of evening started to creep in, her hair was unwound from its bun and her long skirt was tangled up at her knees. She straightened herself in the bathroom, and Jabowen led her double-time down the great, curving staircase as though it were no more than a fire escape. He drove her to the ACT! parking lot, where she’d told her father to pick her up at six, and he waited with her there, gentlemanly, for the fifteen minutes until her father arrived. He opened the door of her father’s truck for her, then he reached across the cab, which smelled like gasoline and sweat, to shake her father’s hand. Jabowen’s Mercedes was the only other car in the lot, and her father looked at it a good long time before finally pulling out.

‘Where’d he get that car?’ he said. It wasn’t really a question. ‘I didn’t know you were spending time with a crowd like that.’

The next night, while Julie was washing the dishes from supper, Jabowen called. Her hands dripped on the floor as she cradled the phone between shoulder and chin. Her mother and grandmother were in the living room, building care packages of pamphlets and chocolate for prisoners who had repented and accepted Christ. They had the TV turned to one of their favorite preachers, and Julie could hear the angry, damning cadences of the man’s voice but not the content of the sermon.

‘We can’t do that anymore,’ she said quietly. The door from the kitchen to the garage was open, and her father was out there clattering around in his toolbox for something to fix the refrigerator, which that day had leaked a puddle of icy water across the kitchen floor.

Jabowen breathed into the phone. ‘Don’t you like me?’

‘I like you.’

‘Then why? Is it because I’m black?’

‘Of course not,’ she said. How could she pull apart all the layers of prohibition, much less list them over the phone? Especially when the prohibitions were so at odds with her desires. ‘It’s just – Mr A wouldn’t like it.’ Before Jabowen could argue, she hung up.

That was only two weeks ago. They have hardly spoken to each other since, except as Othello and Desdemona.

On the trip from Lafayette to New Orleans, Julie rides in the second van, driven by the easily rattled Mother A. Whenever Mr A veers into the passing lane to speed around a big rig, Mother A says, ‘Oh, J. J., oh, J. J., God help us,’ before she jerks her van behind his and creeps ever so slowly past the truck, lingering dangerously in its blind spot. A few times Mr A has slowed, waved them alongside, and motioned for Mother A to lower a window so that his van can serenade hers with songs from the ACT! vaudeville routine – Hello my baby, hello my honey, hello my ragtime gal!

‘Use every minute!’ he shouts, and motors ahead.

Julie, who does not want the responsibility of soothing Mother A’s nerves for two hours, has let Monique take the shotgun seat. Monique’s long legs are draped across the dashboard and she’s reading a magazine. When Mother A gets flustered, Monique says, without looking up, ‘Settle down, Mother A, settle down.’

Her empty stomach heaving and groaning, Julie sits in the stale air of the very back, at the end of a row of the little ones, who have, after an hour on the road, mostly fallen asleep. In front of her, a fourteen-year-old girl and an eight-yearold boy are turned toward each other, slapping hands in a complicated rhythm and chanting. When one of them misses a beat, they dissolve into giggles and paw at each other.

By the time they have pushed through New Orleans traffic and reached the water park, everyone, especially Julie, is thirsty. But they are scheduled to perform in less than an hour, and since they will first need to visit a restroom, there is no time to stop for drinks. Mr A enlists one of the boys to carry the jug of Gatorade from the van and one of the girls ferries the Dixie cups. Rations will be distributed when they get to the stage. They assemble in their usual line and trace their way through the maze of paths, twice making wrong turns and stopping to consult a map on which distances are not at all accurate. Waterslides and chutes in primary colors tower all around them, some several stories high, and from every direction come delighted screams, sudden splashes.

They are moving fast, and Mr A has not once turned around. He charges ahead, yelling over his shoulder for everyone to keep up.

Jabowen strides easily at the head of the line. Monique traipses after him. Behind Julie, the boy with the Gatorade stumbles and drops the jug, has to chase it as it rolls into the grass on the side of the path.

At the back of the line, Mother A, bent forward with the effort of keeping up, says again and again, ‘Lord, this heat!’ and fans herself with the folded map.

Julie’s lips have started to parch; her stomach has not recovered from the ride. Every time she passes a kiosk selling lemonade and slushies, or steps over a puddle of water in the path, she is acutely aware of a clenching, twisting fist around her kidneys.

Once, she calls out to Mr A, but he barks, ‘Not now!’ without glancing back, as though she were just any other kid in the line.

When they reach a restroom, Julie is of course in charge of getting everyone through in a timely fashion. She stands near the row of sinks, ushering little girls into empty stalls, helping them with buttons and snaps and shoelaces that have come loose, reminding them to wash their hands. If there is ever a moment when no one is entering or leaving a stall, she tries to get a drink of water from the sink. But because the faucet knob is spring-loaded it will run only as long as she holds it on, which means she can collect barely a sip of water at a time in one shallow cupped palm, or else she must bend down to the stream and slurp.

With only ten minutes until the performance, they finally reach the stage. Although there are tree-shaded benches and lawns all around, the stage itself is in full sunlight, and now, at nearly two o’clock in the afternoon, the temperature is creeping toward 100 degrees. Mercifully, Mr A has them sit under the trees. To Jabowen he hands the Gatorade, to Julie the Dixie cups.

As she moves toward the clusters of kids, seated Indianstyle on the shaded grass, her skin feels like wool; the heat was bad before but now it is unbearable. She tries to hand a cup to the kid she knows is sitting right at her feet, but suddenly she cannot see him. A blackness has crept across the ground and swallowed Julie to the waist. She hears herself say, ‘Where are you?’ Someone else says, ‘You should sit down.’

And then she is swallowed completely.

When she comes to, she thinks at first that she is at a church picnic, that she has been napping on a blanket with her MeeMom. The branches of a tree spread above her. A chorus of song wafts not far away. But the presence she thought was her grandmother is not her grandmother at all. It’s Mother A, fanning her with the map, laying a cool, wet handkerchief on her forehead.

Julie leans up on her elbows. The kids of ACT! are already on, and Mr A is hovering near the stage. A crowd has gathered in the bleachers. Jabowen and Monique come forward while the rest of the kids recede.

‘I told him we ought to take you to the hospital,’ Mother A says, ‘but he won’t listen.’ This is the first word of criticism Mother A has ever had for her son. She hands Julie a cup of Gatorade and refills it three times. ‘If it was that young man laying here in the grass right now, there would’ve been a doctor called, I can tell you.’

Julie drags herself to a sitting position against the trunk of the tree. Onstage, Monique thrashes, her tiny throat pinched between Jabowen’s hands, then crumples to the ground.

‘He wouldn’t want to jeopardize the money, is what it is.’

Julie stares at Mother A, perplexed.

‘From Jabowen’s daddy. For the company.’ He’s the one paying for all of this.

The show is done and the band of kids comes laughing and wound-up back to the shade under the trees. The little ones surround Julie, overly attentive, until Mr A shoos them back into formation and squats by her side.

‘How do you feel, babe?’ he says. He slides his left hand under the back of her neck, lifts her long hair. His right hand moves up and down her arm, shoulder to elbow.

Is it the same? Julie wonders. Is the way he touches her exactly the same as how he touches Jabowen?

Mr A takes his left hand from her neck, moves the right hand to her thigh. He pats quickly three times, already distracted by what’s happening among the kids, in this case Jabowen and Monique, who are replaying the Othello scene, but in reverse.

‘But half an hour,’ Jabowen squeaks. ‘But while I say one prayer!’

Monique, in a deep bass, bellows, ‘It is too late!’ and lunges for Jabowen’s throat.

Mr A has promised them pizza after they check in to the next motel and rest for a few hours. Later, too, they will call their parents, to assure them that no one is dead in a ditch along Interstate 10. For now, Mother A has gone down to the motel restaurant for a cup of coffee and some time alone with a ladies’ magazine, and Julie has been sleeping, finally, on one of the beds while the other girls color or read or pass notes and whisper or doze off themselves.

Julie is sleeping so soundly, in fact, that she does not hear the knock at the door, the filing in of seven slouching boys who have been expelled from their own motel room. The boys find places as best they can in the overcrowded room, in corners, under the table, one of them on the edge of the bed where Julie is sleeping, and this is what finally wakes her.

Puffy-eyed, muddled, she sits upright, pinches her eyebrows together. ‘What are you doing here?’ she asks the boy, then takes in the room. ‘What are you all doing here?’

Monique is standing in front of the mirror, hand on a cocked hip, watching her own reflection. ‘Mr A sent them here.’ She raises one leg in an arabesque, nearly kicking another girl in the face. The boys stare at Monique’s lifted leg. Someone suggests a game of charades.

Julie doesn’t even bother to think of a pretense. She kicks off the covers, picks her way around the kids on the floor, and pounds down the walkway to the boys’ room. She knocks, hard.

Jabowen opens the door in his boxers and undershirt. ‘Oh,’ he says. ‘It’s you.’ He moves aside to let her in.

Mr A is lounging on the bed. He too has shed his sport coat and pants, but wears an ACT! T-shirt many sizes too big and boxers with yellow happy faces. Skinny and startled, he reminds Julie of a hermit crab plucked from its shell. Before him is the Scrabble board. Tiles are scattered across the quilt and he is dropping them by the handful into a velvet bag.

‘Scrabble! Come sit down, babe.’ Mr A pats the bed. ‘You can still get in on this game.’

Jabowen hands her the velvet bag. ‘Draw your tiles,’ he says.

They settle together on the bed. Julie draws her tiles, as she is told, and arranges them on a rack: q t n a y d c. She knows there must be a word in there to lay on the board between Jabowen’s and Mr A’s, and she shuffles the tiles around trying to see it. Mr A is prompting her, gently teasing, talking a little trash. Jabowen stares seriously down at his own tiles. Her bare legs and Jabowen’s bare legs and Mr A’s bare and hairy legs are all at angles on the bed, nearly but not touching. Jabowen is rattling tiles in his hand, impatient. Julie stares at her own.

She stares so long that Mr A leans over to help. He points to an available S on the board. ‘nasty,’ he says.

Now Jabowen leans in too and says, ‘dynast. ansty. stand. sand. stay. Just pick one and play it, Jules.’ He finds Mr A’s pinkie with his pinkie and strokes it.

She wasn’t meant to see.

Or she was and it’s nothing. Her tiles blur. By heaven, I saw my handkerchief in ’s hand! But seeing is not all. She has learned this, at least, from Shakespeare and from church. One can see indeed yet perceive not, hear indeed yet understand not, divide the world in accordance with rules – Othello but not Desdemona, divine messengers but not demons, culottes but not shorts, affluent but not white, beardless but not vulnerable, innocent but not chaste, passion but not lust – yet fathom not the division.

‘Double letters,’ Julie says. ‘The rule is double letters.’

Jabowen and Mr A stare blankly at her, then Jabowen, understanding, reaches over, pats her on the head. ‘Very good, kid,’ he says, ‘but that was two days ago. We’ve moved on to Scrabble. For heaven’s sake, play your word.’

Image © Can Pac Swire

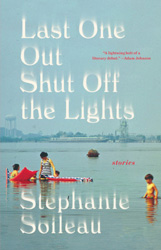

This story is included in Stephanie Soileau’s debut collection Last One Out Shut Off the Lights.