I write short stories. Different kinds of short stories. Some angry, some thoughtful, a few designed to unsettle. I employ various forms, with a playfulness picked up from my training in poetry (where it’s always fun to smack negative capability and reader-response theory about).

Don’t get me wrong: my stories do have a story: that is absolutely the case. Characters move, events are caused, outcomes are understood. And yet often, for me, a short story is a loose-knit sweater, a trawler’s net, where the spaces and holes are inseparable from the whole, and yet where, in their reader, they can chime, provoke, or be filled by memory (or the simulacrum of memory).

*

It’s the summer of 2011. I am in the final stages of my prose fiction MA, completing my assignments as I apply for the PhD funding I so desperately need. My room in Ealing is crowded with books, with piles of stories and poems that might be good enough, might be terrible, and then I realise nothing I read is making sense.

Words are changing as I look at them. Walking is working, collect becomes connect, or context, or couldn’t. The letters are changing, moving, vanishing.

Go ng, Go ng, Go e.

What’s this? I ask, holding the page up to my eyes. The words slide away, changing their letters again as I bring the paper forward, push it away.

This is not what words should do.

Eventually, I realise the problem. Someone has left a floury thumbprint on the screen of my vision. This smudge, this spot of greyed-out blankness, sits just to the right of centre. For distance vision, it’s not too bad. On a white page, or on a screen, it is devastating. I become unable to read, as my helpful brain starts filling in the gap with its best guess.

Maybe it’s one of those painless migraine things, I think. Time to take a break.

I shut down the laptop, take some pills. Drink lots of water. Go to bed.

The next morning, the gap is still present: a persistent blob of nothing-much, just hanging around in my sight. I ring my mum, and then ring my optician for an emergency appointment. They send me to Moorfields Eye Hospital.

I have a dissertation to finish, creative submissions to trim and shine.

But I cannot read (because there are gaps).

But I ca ot ead, (so my brain fills in those gaps).

So I carrot bread. (Because my brain is unhelpful.)

*

The doctor at Moorfields is impatient with my tears. Brisk and bright, she confirms that the structure of my eyes is sound, and that she can see no organic cause of my trouble. No one mentions brain tumours. No one talks about death. I cry anyway, and she can barely stop her own clever, working eyes from rolling, which, of course, made me cry all the harder, as I try to explain that I must have words, must be able to write. I no longer have a job, with its precious sick pay. My MA funding is ending, and I have no idea what comes next.

Of course, her impatience is justified. She is giving me good news, maybe a rarity in her work, where she likely deals daily with all manner of bodily betrayals, so many stories with unhappy endings.

I think it will go away itself, she says. But we’ll send you for an MRI, if that will make you feel better.

It does.

A little.

*

By the time my MRI appointment comes, I have been struggling to work around my carrot-bread concerns. My flatmate catches me wearing two pairs of glasses, my reasoning based on half-remembered lens technology, and tells me off for being foolish while baking me a cake. Another friend lends me an electronic typewriter, a clunky, funky, solid word machine, but too unforgiving for this non-touch-typist to use. Turning once again to my laptop, I set the font size on Word to thirty-six, then seventy-two points.

The dissertation is nearly done. I think it is good, that I worked hard and wrote well. As I lie in the MRI, eyeballs vibrating, I sing pop songs in my mind, trying not to think of the future for a writer who cannot write, a student who cannot study. I try not to think of the bridges to my past life, how it had felt to douse them in petrol and kiss my fingertips to the flames.

*

Two weeks later, I wake to find the carrot bread has gone.

In relief, I start to process my experience. The gaps in my vision had not prevented me from reading. Instead, they gave me an increased opportunity to co-create the text, inserting my own lexicon, my preferred direction, into the books and articles I’d struggled with every day.

I mused upon this, on the necessary, invited, generous presence of the reader. If I offer them the framework of whole, yet fictional worlds, where the logic is recognisable, the physics complete, how would their own minds fill in the gaps? Would they notice the effort and become wearied, resentful at being forced into an act of creative labour they didn’t want? Or – and here is my focus – could the co-creation occur so naturally that they don’t even notice?

*

Even though my eyes are working again, I still attend the consultant appointment. I am enthralled by MRI scan’s movement; each time he hit the space bar, twin globes of jelly emerge from my blob of brain, then recede. There are paths and knots and swirling things. My secret garden on display.

Looks good to me, the consultant says. Probably an infection in your brain. We didn’t see anything in your blood tests, but these things can happen.

He shrugs. Give us a ring if it comes back.

*

It’s the spring of 2020, and I haven’t called him yet. I am writing a carrot-bready story that plays around with spaces and gaps. As I read over, I wonder if I’ve strayed into poetic unintelligibility – after all, there’s a universe between the blank page and custard-thick prose that yells here’s the point (although I concede the former is much more destructive, for reader and writer alike).

So I take a break. My daily lockdown walk takes me through the car park of a gym. Lawn cuttings and dropped blossom hide the markings on the floor, and I consider spaces that aren’t spaces, gaps that aren’t gaps, and how clever, how helpful, how good.

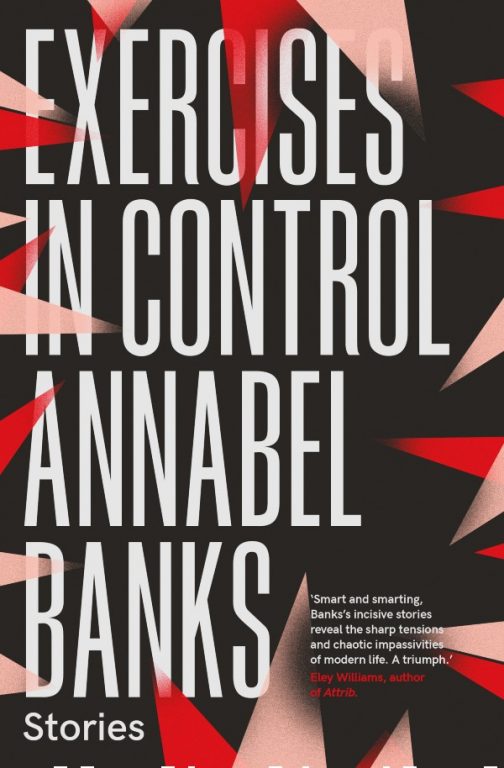

Annabel Banks is the author of

Exercises in Control, available now from Influx Press.Image © Hans B. Sickler