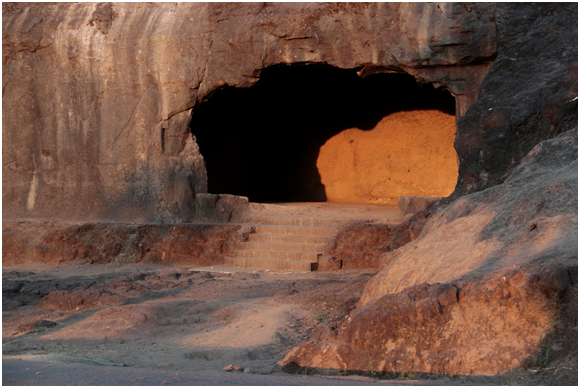

Nothing, not the unbounded sky. Nothing, not the seven and a half acres of land with its fruit and flowering trees each season on which she lives, not the devotion of the Buddhist monks from Cambodia and Thailand who come for the day to visit the great caves and prostrate themselves on their undulating stone floor, not the sudden, unseasonal March thunderstorms and rain and hailstones that last a week and destroy the wheat and leave the farmers bereft, nothing. Nothing, nothing, nothing, not the great Buddha in the caves next door for what can stone do or say or impart or move, nothing. Not her own face hammered and chiselled by her loss as if into its original form. No longer the flabbiness that comes from having received too much love, the stout body shaped and nimble now that the comfort and security of love has been taken away. The passage to beauty not slow but sharp and cleaving, to others, something, to her, nothing, nothing. Not the village women who squat and withstand and tend the land on which these cottages have sat for twenty-one years making a sprawling hotel and retreat for scholars, artists, people of faith, monks and seekers. Not the red vented bulbuls which come back every twilight to sleep in the tree near the fence, returning when there is barely any light left in the sky so that the red on their bodies cannot be separated from the darkness. And almost nothing is what she eats even almost a year after his death, only three spoons of rice and dal at each meal, and perhaps some vegetables, not even rotis which can no longer go down her throat, eats this almost nothing as she works at her desk doing accounts and overseeing the whiteness of the towels, the food being cooked in the enormous kitchen, the pruning of the rose bushes. Nothing, nothing, not the nearby small town of ruined medieval mausoleums and graves where Sufis, some of them from Arabia, are buried by the hundreds, now become nothing, the way they wanted. Not the lame hunchback in white who prays at one particular grave each day at sunset and walks slowly backwards till the grave has vanished out of his sight, in time with the light. Not the returning visitor who comes with condolence and compassion, and her tears come without a struggle to stop them as she talks to this visitor and she does not raise a hand to wipe away the wetness, there is no need, I am alone, alone, alone and nothing, she says. Not the Buddha, nor Siva nor Durga in the caves across the fence from her land, watching over the centuries, their faces always twice lit, by that imperceptible smile on the face and by fragments of the flexible sunlight that have bent and twisted inside according to the season. Both are sources of light that have never paled even though time has often caused a crack through the head, destroyed a large hand raised in the abhaya mudra, fear not, fear not, leaving the arm as a stump, or smashing a breast, the face has remained lit, a lamp in a windless place, changing nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. Nothing, for no hillside exploded and cracked over years, nor its carving by thousands of craftsmen through the centuries, neither the multitude of faiths, neither faith nor its defiance, not the Buddha who worked like a labourer at suffering, his hammer rising and falling in comprehension, nothing can bring her even a wisp of solace, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. Not the order of the days and seasons that forever return and never falter, and what has been achieved turns into failure, becomes nothing, so that people have to begin all over again, what has already been changes into what is likely to someday become, so that once again the hillside must be exploded, the sky pulled in from above, and till then, perhaps, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing.

The rosy starling appears in flocks on the Indian coral tree as it flowers, in late March and early April. Its body has a rose pink mantle and breast, the head and wings are a deep, shining black. Thirty-one thousand of them die this season when unseasonal rains come, and with it days and nights of hailstorms. Red-rumped swallows have dark metallic blue and chestnut bodies, and a long, deeply-forked tail. They wheel and bank in acrobatic flight as they call. Hundreds die in the hailstorms that break and flatten the sugar cane and wheat. Rose-ringed parakeets are bright grass green, with a rose ring around the neck, screech as they fly, raiding fruit orchards and cultivated fields. Fifteen hundred of them die in the hailstorms as they are roosting on teak trees near a farmland. The singing Oriental skylark is a dull brown bird, with a round crest on its head. It rises high and drops low in its flight, sometimes hovering for a time in between. It is among the twenty-six species that are destroyed. There is almost nothing upright in the fields except the sturdiest trees. Everywhere there are the flattened stalks of crops, broken fruit. The tiny purple rumped sunbird is only four inches in size, barely larger than the two inch hailstones. Purple on the throat and rump, a metallic green crown and shoulder patches and a deep maroon collar, it is a restless bird of foliage, regularly visiting flowering plants. Sparrows die, and red-vented bulbuls, and mynahs, and the larger francolin partridges, black drongoes, coucals, koels, quails, doves, cattle egrets, black-headed ibises, painted storks, ruddy shelducks, northern shovellers and owls, bringing the number of deaths to over sixty-five thousand. The land is strewn with the wreckage of broken nests, smashed eggs and the most delicate bones.

When a great loneliness has been attained, when there is no assurance, when the self is threadbare, ragged at the edges, when a life is so shaken out and empty that there is room in it for every object and being it watches, it is then that the ragged self sees through the muscular light, through the complex, melodic call of the unknown bird which never shows itself, and does not stop seeing, it finds a transparency in things that leads to their sources, whether that be a season or a man, the black clay horse with a benign sadness in its eyes leading to the hands of its maker, so nothing seems to have a definite end, and it moves towards each thing as easily as night towards day, so that the distinction between what is human and what is not falls away, and this is a knowing that cannot be lost as strength can or the ability to love, from this an enormous power unleashes itself that looks from the outside like complete powerlessness, and the evening wind from over the sea makes that threadbare self billow like a tattered sail, all that resisted it now become the air on which it rises, so that what has come to stay can regard the clear spring night, regard the new stars, regard the different trees, as variations on a life span, each not to itself but to the other standing witness.

Featured photograph by Johan Fantenberg

In-text photograph courtesy of the author