‘I ordinarily answer such as ask me the reason for my travels, “that I know very well what I fly from, but not what I seek.” ’

– Michel de Montaigne, translated from the French by Charles Cotton

1

In 1890 Anton Chekhov took an axe to his life. He went to the prison island of Sakhalin, more than 4,000 miles from his home in Moscow. The journey took him eleven weeks by road, river and sea. His three months on the island were spent mainly in the capital, Alexandrovsk, interviewing convicts and former convicts, voluntary exiles, administrators and prison overseers. The resulting description of squalor, mass sexual abuse, incompetence and systemic cruelty at the far edge of the empire would become a cause célèbre back in European Russia when it was serialised, then published as a book, three years later, and lead to a secret government inquiry into the running of the penal colony. ‘I regret that I am not a sentimental person,’ he told his publisher before he left, ‘otherwise I would say that we should make pilgrimages to places like Sakhalin as Turks go to Mecca.’

At the derelict harbour in Alexandrovsk, as I was taking a photo of a plaque commemorating his arrival on the island, there was a pain in my calf so deep and startling that I was caught, like Buridan’s ass, between shrieking and puking, and instead ceased, for a while, to breathe. It was my fault: the dog had been barking from its lookout of rubble with that squint-eyed ripping motion of serious dogs, and I’d turned away. It did its job so well that all memory of its appearance has gone – big or small; what breed or colour. I took off my sock and tied it around the wound and, my shoe slopping with blood, flagged down a car.

Pushing the needle into my back an hour later, the nurse said, ‘Now you have something to write about, don’t you?’ The doctor battled an undoctorly smirk while jotting down his notes.

I went back to the town’s solitary hotel, the Three Brothers, shook the blood from my shoe into the toilet, swallowed some antibiotics and went to bed. Next morning, when I was told that a minor earthquake had struck while I was sleeping, it didn’t come as a surprise, and not only because Sakhalin lies in a region of seismic unrest.

2

In Moscow a week earlier the intersections around Red Square were blocked by orange municipal dump trucks; bullet-vested police were guarding the approaches and by 9 a.m. bands of bearded young proto-Cossacks were standing in circles roaring battle songs into the sky. It was Victory Day, celebrating the surrender of Nazi Germany, and later President Putin would be addressing the troops. By design or accident, an international a cappella festival was on at the same time. The outdoor stages were set up in the same squares as makeshift screens playing looped war footage, so that the singers’ earnest harmonising – a beatbox version of ‘Superstition’, for instance – vied for your attention with, say, the Red Army Choir doing ‘Arise, Great Country’, reaching an equilibrium of volume that became intolerable until the a cappella people hit the chorus.

On Pushkin Square 300 members of the Moscow Communist Interbrigade were carrying flags bearing the hammer and sickle and Lenin’s face. Among them was a green flag with another stencilled likeness – Che? No, Gaddafi. ‘Net kapitalizmu! Net fashizmu! ’ a man was chanting into a loudhailer. Over the heads of the crowd it was possible to glimpse, beyond the barricades, a ballistic missile as big as a grain silo creeping down Tverskaya towards Red Square.

Meanwhile, a mile away, Putin was mid-speech: ‘Our nation is well aware of what war is. It brought grief and immeasurable suffering to every family. We have not forgotten anything. We remember everything . . .’

But the past wasn’t for everyone. In the bars of Kitay Gorod half the women seemed to be wearing the same brand of denim trench coat, printed across the back: ‘Good things come to those who hustle’.

In the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts I lingered over Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Fall of Man: Adam and Eve as pale and delicate as rhizomes, about to be kicked out of the Garden of Eden. No longer innocent, maybe, but they can’t really comprehend what their new life will be like.

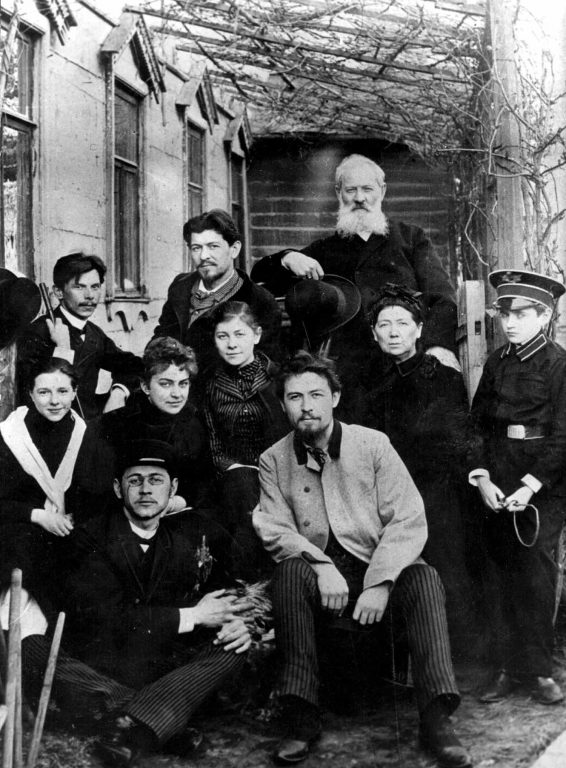

Chekhov’s house on Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya Street, now a museum, was closed for refurbishment. There’s a famous photo of him taken on the veranda just before he left for Sakhalin in spring 1890. He’s barely thirty, surrounded by family and friends. They’re all dressed in black except Anton Pavlovich, who is wearing a cream overcoat. He’s raring to go; you can see it. It is an image of love and pride, the special son; and an image of all he was abandoning.

3

Although Siberia had been a place of banishment for Russia since the 1600s, in the late nineteenth century the number of criminals and political exiles sent to its penal-labour sites became unsustainable. By 1876 some 20,000 convicts were arriving each year. Prisoners were dying of exposure, malnutrition and disease. Escapes and crime soared, and there was insufficient labour to occupy those who remained. According to one visiting ethnographer, the region resembled a ‘battlefield’. A large, sparsely populated, coal-rich island in the far east promised to serve the dual purpose of relieving the pressure on Siberia and consolidating the Russian frontier. Writing to his sceptical publisher, Aleksey Suvorin, a few weeks before he left, Chekhov explained that ‘Sakhalin is the only place, except for Australia in former times, and Cayenne, where one can study a place that has been colonised by convicts’.

At more than 28,000 square miles, almost as big as Austria, Sakhalin is Russia’s largest island. It sits in the Sea of Okhotsk opposite the Amur River delta, separated from the Russian mainland by less than five miles at its closest, its southernmost tip twenty-eight miles north of Hokkaido, Japan. It is not a St Helena in its remoteness. But by the time Chekhov arrived in summer 1890, it was already notorious. According to contemporary commentators, it was ‘the final destination of the unshot [and] the unhanged’, a ‘land of moral darkness and abject misery’. To Suvorin, who was not persuaded of the subject’s urgency, Chekhov wrote, ‘Sakhalin may be uninteresting . . . only for a society which does not exile thousands of people there and does not spend millions on it . . . we have driven people tens of thousands of versts through the cold in shackles, infected them with syphilis, perverted them [and] multiplied the number of criminals.’

What drew him to make that interminable journey from his world’s centre to its furthermost edge? Are there clues in his biography? A year before he set out, his brother Nikolay had died from tuberculosis, and Dr Chekhov was now periodically coughing up blood himself (he too had tuberculosis). He must have realised that such a demanding journey, three months of snow and mud, might kill him. His farce The Bear had been a triumph; his story ‘The Steppe’ had won the Pushkin Prize. He was known and admired. But he had been stung by criticism that his work lacked political conviction. ‘Sakhalin is a place of unbearable suffering,’ he told Suvorin, ‘on a scale of which no creature but man is capable.’ Here was a project. Finally, according to her memoirs, there was Lidiya Avilova – married, twenty-four-year-old Lidiya, with whom he may or may not have been in love.

The conflation of quest and flight is so common among travellers as to be a cliché, but I felt there was more to his decision than either grief or escapism, or a compulsion to bear witness. Look at the photo taken in the relative warmth of Moscow in April. You would not know he is sick. You wouldn’t know that something is drawing him to coldness.

9 May being also the feast day of St Nicholas, patron saint of travellers, I went and lit a candle in the Cathedral of the Assumption – for the journey ahead and for my father, 1,600 miles away. At Christmas he had started a course of intensive radiotherapy. In March he had first one heart attack, then another; then pneumonia and a suspected stroke. There had been a week when we expected him to die. Now he was in hospital, unrecognisably frail, and delirious. I persuaded myself that nowhere was far away, any more. My siblings were nearby, and even on Sakhalin Island, at the ‘end of the world’, as Chekhov described it, I could be back within forty-eight hours. But whenever I paused, my thoughts returned to him, in his windowless ward, which one evening, hallucinating, he believed was the hold of

a ship in which he had been imprisoned.

4

‘The Siberian highway is the longest, and, I should think, the ugliest road on earth.’ Soon after setting out, Chekhov believed he was about to die. His carriage collided with a mail troika. Thrown to the ground, he was almost run down by a second troika, which stopped just in time. In Nikolayevsk on the Amur River he boarded a steamer bound for the Tatar Strait. It was 9 July 1890. On board were some 300 soldiers and several convicts, one of whom ‘was accompanied by his five-year-old daughter, who held on to his shackles as he climbed up the ship’s ladder’.

From the city of Khabarovsk, almost 500 miles upstream from Nikolayevsk, I took a train to Vanino on the Tatar Strait, a journey of 300 miles and twenty-four hours. At Vanino I waited at the station to be summoned to the overnight ferry to Sakhalin. I drank pre-sugared Nescafé, watched the coal barges discharging and talked to the other waiting passengers, all of them men: a teacher from Khabarovsk, an electrician from Uzbekistan, a lighting specialist from Vladivostok, two Chinese platelayers. No one knew what time the ferry would leave.

‘Allahu Akbar, money-money-money, fuck you, fight you . . .’

The muttering giant was coming home from South Korea; he wouldn’t say what his job was but his duffel bag was military. He was sitting opposite me, glowering at the Uzbek guy. He despised Muslims. Returning from a cigarette, he toed the Uzbek’s parcels: ‘Bomb.’ And grinned. ‘Bomb!’ The Uzbek looked down at his parcels and smiled tightly. People were standing up. The bus to the jetty was here.

‘Perhaps I won’t get anything at all from the trip,’ Chekhov had told Suvorin, ‘but surely to goodness there will be two or three days which I shall remember for the rest of my life, whether delightful or painful.’

5

His ship, the Baikal, entered the Tatar Strait on 8 July 1890, almost three months after he had left Moscow. It was a warm, bright day. ‘The soul is overcome by the same feeling that Odysseus must have experienced when he sailed across an unknown sea and had a dim presentiment of meetings with extraordinary creatures.’

So narrow is the body of water between Sakhalin’s Cape Pogibi and Lazarev on the mainland that until 1855 even the neighbouring Japanese believed Sakhalin was a peninsula, despite the insistence of the island’s Indigenous people that it was surrounded by water. (When in 1822 an English map-maker, John Arrowsmith, showed it as an island, one eminent orientalist called him ‘the most ignorant of those whose occupation is cartography’.) Northern Sakhalin’s largest Indigenous group, the Nivkh, believe that the god of thunder lives beneath the sea between Pogibi and Lazarev, and so it came as no surprise to them when a tunnel ordered by Stalin collapsed during construction and was abandoned. ( Putin has commissioned designs for a bridge at the strait, inspired by the one he built between Crimea and Russia in 2018.)

The ship that would take me to Kholmsk, the Sakhalin-8, was a rust-striped ro-ro used mainly for freight. The stink – burnt diesel oil, tobacco, garlic, reboiled sausage. (The garlic smell, it turned out, was phosphine rat poison.)

The one meal served during the fourteen-hour journey was trayed up during a half-hour slot just after we departed: buckwheat kasha, latex sausage, tea. In one corner of the galley, onions were growing in a bucket.

On deck Evgeni, engineer third class, was taking his cigarette break. He was thirty-one. I was the first native English speaker he’d met; he’d learned the language at what he called ‘river school’.

‘Are the English scared of the Russians?’

‘The government, yes. The people, no.’

The deck door opened and a dog, a Pomeranian, was pushed out, the door closing behind it. It looked at the door, then at Evgeni and me.

Somehow Evgeni knew I was a writer. He or someone else had checked the manifest and googled the foreign name. I asked him if the Sakhalin-8 was a good ship. He smiled and shook his head, seeing that I knew the answer. ‘It is very old. From the USSR.’

To port there was a small splash – there were grey whales in these waters – then another; and I watched a plastic kettle float by . . . Another splash – what looked like a washing-machine door . . . ‘Trash!’ said Evgeni, as a flotilla of smaller objects bobbed past.

Evgeni showed me his phone – pictures on WhatsApp of captured Syrian armoured cars passing through his home city of Rostov on a train. Another of him gangster-posing with a Makarov pistol. He completed his army service six years ago. Did he enjoy it? He asked me to repeat the question. ‘Enjoy?’ he said. ‘No! Boys don’t like the army! Boys like home.’

My cabin, buried three decks down, was a cornerless bunker low in the bow and resembling the interior of a tank. Against the hull there was the intermittent swash of water.

The journey to Sakhalin for most convicts was entirely by sea. Just over a year before Chekhov set out, a young Ukrainian named Lev Shternberg underwent the two-month voyage from Odessa. Born into a devout Jewish family in Zhitomir, central Ukraine, in 1861, Shternberg was just fifteen months younger than Chekhov. As a teenager he organised gatherings where he and his friends ‘noisily discussed the burning issues of the day’. He read Darwin and Heine, Belinsky and Dobrolyubov and Marx. By the time he finished high school he was a staunch socialist, and when the populist movement Narodnik, then sweeping Russia, underwent a schism, he was drawn to the more radical, violent faction, Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), which was dedicated to the socialist overthrow of the government. In 1881, the year he entered the physics and mathematics department of St Petersburg University, the city was shaken by Narodnaya Volya’s assassination of Alexander II. Shternberg, who had not been directly involved, was nevertheless fortunate to escape the crackdown against dissent that followed, which included the mass arrest of his Narodnaya Volya associates, many of whom were banished to Siberia. Far from heralding a new socialist republic, the assassination prompted an increase in state repression, while the peasantry the assassins had hoped to inflame into revolution instead turned against the Jewish minority it blamed for the killing. Furthermore, under emergency laws instituted by Alexander III, anyone so much as suspected of sedition was exiled to Siberia.

In 1884, undaunted, Shternberg published a pamphlet entitled ‘Political Terror in Russia’: the intelligentsia, he wrote, must ‘use all the means available to it to overthrow the tsarist government’. Three years later, as editor of Narodnaya Volya’s newsletter, Shternberg was finally arrested and imprisoned in Odessa for two years, before being sentenced, without trial, to ten years on Sakhalin. His ship, the Petersburg, left Odessa on 29 March 1889.

Crossing the Black Sea, it navigated the Suez Canal to Aden, before sailing on to Colombo, Singapore, Nagasaki and Vladivostok. An observer on the same ship wrote that the journey ‘recalled the most terrible scenes of Dante’s Inferno . . . storms at sea, heat under the tropics, cold in the North Pacific [and] dirt surpassing anything the most vivid imagination could picture’. Unlike many of his fellow Populists, Shternberg never repudiated religion – the prophets were his inspiration. The voyage to Sakhalin seems to have intensified his faith. When the Petersburg docked at Port Said, he noticed the date on a newspaper: tomorrow was Passover. Gazing at the mountains of Sinai, he understood his plight as the perennial plight of his people; crossing the sea that the Israelites had crossed, he saw himself as one ‘who also sought freedom’:

freedom not for his own people but for another people dear to him. This descendant was now destined to make a great journey, not to the Promised Land, but to the land of exile, thousands of miles away . . . And suddenly sadness disappeared from my soul and a new feeling overcame me, a feeling of pride . . . It seemed to me that a great fire had ignited in my heart, so that if millions of my dispersed brothers were with me at the moment, I would have had enough strength to use my fiery words to burn away from their hearts all impurities brought into them by centuries of oppression and slavery, and ignite a new fire in them, which would have lifted them up to the highest ideals of mankind.

He finally reached Sakhalin on 19 May 1889.

Shternberg’s fate, and the transmutative effect of his exile, were a reminder that Chekhov, for all his courage, was a tourist. Nobody had invited him, still less compelled him. Indeed, until Chekhov reached Alexandrovsk he remained uncertain that he would even be granted permission to land. ‘Just why did I come here?’ he asks himself. ‘My journey appeared frivolous in the extreme.’

I lay in my cabin, with the light on, and remembered the night when my father thought the oncology ward was a ship’s hold, rusted, dripping, booming.

At 4 a.m. I was shaken awake by someone banging at my door.

6

Sakhalin is often described as sturgeon-shaped, and it does resemble a fish, a long, slender, bony fish, with two peninsulas in the south forming a forked tail, and another, resembling a dorsal fin, extending eastward into the Sea of Okhotsk. The southern half of the island is mountainous, dominated by two parallel chains, the Eastern Sakhalin Range and the Western Sakhalin Range, separated by the floodplains of the island’s two rivers, rivers that somehow seem too great for the land mass they drain: the Tym, which flows north-east, and the Poronai, which flows south. The north is flatter, wetter, barer, colder and windier, mostly bog, tundra and open taiga, its coastline a scalloped lattice of lagoons. Off the north-eastern shore lie the vast oil and gas fields of the Sea of Okhotsk shelf. Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky, Chekhov’s ‘Alexandrovsk’, lies halfway up the western coast, where the mountainous south meets the boggy north.

It’s hard to imagine the fear and contempt the word Sakhalin conjured among the populace of tsarist Russia. According to a visitor writing in 1903, ‘the very name of the island is banned in St Petersburg’. Not so much a Guantánamo as a black site. ‘God is high in the sky, and the tsar is far away,’ went the Siberian saying, but here both entities alike were as nothing.

When the first convicts landed at Alexandrovsk in the early 1860s, south Sakhalin, then known as Karafuto, was under Japanese control. Only when Japan ceded its territory to Russia in 1875 did the authorities start sending criminals in large numbers. By 1888 it was the largest penal settlement in Siberia. Any man sentenced to more than two years and eight months, for any crime, could be sent there, as could any woman under forty serving more than two years.

As well as common criminals and a handful of political deportees, there were three further categories on Sakhalin. ‘Settled exiles’ had completed their sentence but were obliged to remain on the island. After six to ten years they became ‘peasants-in-exile’, free to leave provided they did not return to European Russia. Thirdly, there were those who had come to the island voluntarily. ‘The clever are brought here,’ went an island saying; ‘the idiots come on their own.’ Among the ‘free’ were the wives of convicts, many of whom were enticed by letters from their husbands describing a land of warmth, fertility and opportunity. By the time of Chekhov’s visit there were some 6,000 penal labourers on the island and 4,000 ‘settled exiles’, most of them living in and around Alexandrovsk and the southern port of Korsakovsk.

Because Sakhalin’s roads are mires in winter and rutted dust bowls in summer, it’s best to travel by air or rail. My train pulled into the town of Tymovsk, fifty miles east of Alexandrovsk, just after dawn on 13 May. When I had left the modern-day capital of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk the previous evening, the train had passed through sidings thick with fresh young bamboo ( Japan is barely a hundred miles south of Yuzhno) and the birch taiga had been coming into green: in the dark of the forests, the young leaves were as bright as the spots of light from a glitterball. But as we drew into Tymovsk, 270 miles north, there was little colour and the ditches were still packed with snow.

I was met by Alexander, a driver sent by the director of the Chekhov Museum, Temur Georgiyevich Miromanov, who was also the town’s former mayor. My contacts in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk had mentioned Miromanov’s intellect; they also admitted that he scared them. It was unclear if he was directly employed by the federal security services. On the ferry there had been a thin, grey-faced man in an oversized black suit, whom I became convinced was watching me; there were the two young men who sat in on my meeting at a museum in Nogliki, unintroduced and thumbing their phones as I spoke; then there was the translator who, sitting down on the sofa in my hotel room in Yuzhno, looked up at the light fittings and the smoke alarm and waved and said, not quite joking, ‘Hi, guys!’

The road to Alexandrovsk rolled through taiga swamped with snowmelt. Water flowed everywhere. It was as if the island had just been winched out of the sea. Around the borders of the forest bogs were the blooms of Asian skunk cabbage. Alexander let out a flurry of grunts and squeals – it took me a moment to realise he meant the plant was used as pig fodder. Its white spathes, resembling arums, were flame-like or jug-like or like hands in benediction, rising out of the anaerobic black in groupings that seemed to correspond to the clustering patterns of anxious human crowds.

We stopped for a smoke at a churned-up field where victims of Stalin’s purges had been shot and buried, hundreds of them. From the hills the road followed the streams seaward through tiers of neat white housing blocks. The road changed from dirt to asphalt. On the town square, where the prison used to be, between the house of culture and the Three Brothers hotel, in pride of place, was a bust of Chekhov.

7

Natalia was a retired English teacher who had lived in Alexandrovsk all her life. She was worried I’d have a poor opinion of her town, of her country; that I would find the hotel, the canteen, the roads uncomfortable. We walked to Alexandrovsk’s fenced-off harbour, with its thickets of knotweed and angelica and its grounded and half-sunk trawlers. When the Baikal anchored offshore on the evening of 10 July 1890, the hills surrounding the town were aflame. ‘Through the darkness and smoke spreading over the sea,’ wrote Chekhov, ‘I could not see the landing stage or buildings and could make out only the dim lights of the post, two of which were red . . . it looked as if the whole of Sakhalin were ablaze.’ He did not need to add that it was ‘as if we were in hell’.

Lev Shternberg’s initial impression of the island, fourteen months earlier, was more positive: he was met by the ‘courteous’ district head, who explained that, as a political exile, he would be granted an allowance, spared hard labour and permitted to take paid office work. However, he wrote to a friend, ‘my own privileged position does not make it easier to watch the suffering of people deprived of all their rights’. He was also struck by the ill-treatment of the island’s Indigenous population. Soon after arriving he saw an old Nivkh man being harangued by the children of the bathhouse owner. ‘Some day I will study them,’ he wrote in his diary. Even for a writer as inquisitive as Chekhov, the Indigenous population of northern Sakhalin was little more than an incomprehensible shadow at the edge of his field of vision. The Nivkh, the largest Indigenous group on the island today, are one of the five Indigenous peoples of eastern Siberia known by ethnologists as ‘Palaeo-Asiatics’, whose languages have no known connection with other linguistic groups. (Nivkh, famously, has twenty-six different ways of counting from one to ten according to the physical and social characteristics of the thing being counted.) Traditionally they were semi-nomadic fishers, with an animist belief system based around four ‘spirit masters’: the sky, the hills, water and fire. Today most Nivkh live on the other side of the island, in the oil towns of the north-east, having been displaced from their traditional settlements under Soviet collectivisation.

‘Nothing is sadder than a boat on land,’ said Natalia, gazing through a gap in the hoardings surrounding the harbour. Pining for the past was a form of self-comfort, and near ubiquitous among those I spoke to on Sakhalin. It was also a way of explaining the corrupt and diffuse present to strangers. Things haven’t always been this way. When she was a child, she told me, the town had 20,000 people and nine schools; today the population is half that and there are three schools. At least in Chekhov’s day the place had a purpose. Now, said Natalia, the young people fled to Yuzhho-Sakhalinsk, Moscow or Vladivostok the moment they left school.

On the outskirts of the town, as in the villages I would see over the coming days, occupied houses were often surrounded by dozens of rotting dwellings shrouded in weeds, home only to feral dogs and the occasional bear. Natalia remembered the sunny days of Young Pioneer camps in the hills; the days when the port was thriving and she and her school friends would return from summer afternoons on the beach glittering with black dust from the coal barges.

Now the coal industry was defunct and the timber firms had moved to Japan. Alexandrovsk, like much of the island, saw little of the vast wealth being siphoned from the oil and gas fields of the north-east (the largest consortium, Sakhalin Energy, reported revenue of over 46 billion in 2018, but most of the tax was skimmed off by Moscow). There were no longer enough fish in the Tatar Strait to sustain the town’s fishing industry, and the water had risen to permanently submerge her childhood beach. Who knew why? She didn’t want to reconcile herself to this present – it was not her country.

A hundred yards offshore, crowned white with bird droppings, was the trio of sandstone outcrops known as the Three Brothers. Half a mile south, on a hillside above the shore, stood a derelict lighthouse, which had recently been requisitioned by the army for some unspecified purpose and therefore could not be visited, I was warned, or even approached. High above the ruins, on the top of the hill, was the site of the old lighthouse – ‘a modest little cottage with a mast and lamp’ – to which Chekhov made regular walks during his months in Alexandrovsk. (There was nothing there now but the concrete footings of a dismantled radio mast.) Chekhov would not stoop to presenting a lighthouse as a symbol of anything, least of all hope, but its setting did promise a kind of transcendence:

The higher one rises, the more freely one breathes; the sea stretches out before one’s eyes, and little by little thoughts arise which have nothing to do with prison, or hard labour, or the penal colony, and it is only up here that one becomes aware of how wearisome and hard life is down below. Day in, day out, the hard-labourers and settled exiles undergo their punishment, while, from morning to evening, those at liberty talk only about who has been flogged, who has tried to run off, who has been recaptured and who is going to be flogged; and it’s strange how you yourself become accustomed to these conversations . . . But on the mountain, in sight of the sea and the beautiful ravines, all this comes to seem impossibly cheap and sordid, as in truth it really is.

Beyond the old landing stage the Tatar Strait was without a hint of colour. As Natalia and I approached the gates to the harbour, two dogs emerged barking from a watchman’s concrete hut. I sized them up, declared them ‘fine’, and turned around to photograph the plaque commemorating Chekhov’s arrival.

8

Natalia had met Miromanov, the museum director, forty years ago, when they were trainee teachers at a Young Pioneer camp. She spoke of him as if he were famous – which he was, in a limited sense. She didn’t think he would remember her. ‘He did something very special. It was really remarkable. He would say, “Tell me any word, and I will make a poem.” And he did just that: you gave him a word and immediately, he would recite a perfect rhyming verse; I don’t mean doggerel.’

Miromanov was shaven-headed and grey-bearded, with the complexion of a fisherman. He was impatient with anyone who was not a young woman. He’d been born in Alexandrovsk, like Natalia, and for a while had been mayor. Before that he had travelled the world. When I asked in what capacity, he changed the subject with such deftness that I only realised he had done so hours later. He was popular, and the way others addressed him, with a cautious smile, suggested he still wielded the power of a person known to be influential. I asked him many questions and not once did he ponder his answer for more than a second, even when it was a snapped ‘I do not know!’ You wouldn’t take him for a museum director or, for that matter, darling of the town’s am-dram soc. (People swooned over his Vanya.)

The Chekhov Museum, located in a traditional wooden house built on the spot where the author stayed, had been run by Miromanov’s father before him: the next day he showed me in with the manner of someone presenting the family business to an investor. The rooms were immaculate, the letters and artefacts (Anton Pavlovich’s desk; Anton Pavlovich’s samovar . . .) displayed with none of the pathos – blown light bulbs, Blu-Tacked labelling, lurking cats – of some Russian regional museums. A cleaner followed us from room to room, wiping the vitrines like the cleaners who glide from icon to icon in Orthodox churches, cleaning lip-smears from the glass.

Soon after he arrived, Chekhov arranged for 10,000 census forms to be printed – ‘my main aim in conducting the census was not its results but the impressions received during the making of it’. These forms, a remarkable 5,000 of which were completed, formed the basis for the book he would publish three years later. The forms included lines for birthplace, year of arrival, literacy level and family circumstances, as well as ‘status’ – whether the subject was free, a ‘settled exile’, a ‘peasant-in-exile’ or a convict.

At the time of Chekhov’s visit, Miromanov said, Sakhalin had four categories of convict. Most slept in the town’s prison, were not shackled and worked each day in the coal mines at Dué (‘a dreadful, hideous place’, according to Chekhov, which lay on the coast beyond the lighthouse). A second group was shackled and laboured for four hours per day. The third and most wretched were the tachechniki, who were chained for life to wooden wheelbarrows. The tachechniki did not work but sat or lay in their cell, the barrow serving only as ball-and-chain. (There were photos of these men standing with their barrows, wearing the expression of those who have discovered that pain is not a finite thing, an expression that might be a sarcastic imitation of one in rapture.) Finally there was a small number of political exiles, numbering no more than fifty at the time of Chekhov’s visit, including narodniki like Lev Shternberg.

9

The dog bite, once the swelling subsided, seemed to kindle a yearning to move. I had read about a village to the north of Alexandrovsk, which had been designated as a kind of exile within exile. In 1890, when the authorities in Alexandrovsk learned about the approach of the famous author, clutching his wretched notepad, they saw to it that one political exile, a tiresome agitator for prisoners’ rights, would not be around to blab. Shternberg had been in Alexandrovsk for more than a year, and had become sickened by the ill-treatment of the convicts he lived among, especially the overseers’ often arbitrary meting out of punishment beatings. One of the most memorable scenes in Chekhov’s Sakhalin Island describes the birch-lashing of a failed escapee, a child-killer named Prokhorov:

Prokhorov’s hair is stuck to his brow, his neck is swollen; after five or ten blows his body, still covered by weals from previous lashings, has already turned crimson and dark blue; the skin on it splits from every blow. ‘Yer Excellency!’ we hear through the screeching and weeping. ‘Yer excellency! Be merciful, yer Excellency!’

Chekhov notes a ‘kind of curious stretching-out of the neck, the sound of retching’. He leaves, unable to watch any more.

Writing a few years later, another visitor, Charles Hawes, describes the plet, a whip with lead-tipped thongs. Hawes tells the story of one victim who, sentenced to a hundred strokes, promised to pay the executioner with a bottle of vodka (then a rare commodity) if he refrained from applying the leaded tips. But with five strokes remaining, the prisoner reneged: ‘You can’t hurt me now; you needn’t think you’ll get your vodka!’ The executioner silently adjusted his stroke. Three more blows and the man was dead. ‘It was only necessary to draw back the plet, as the stroke was spent,’ explains Hawes, ‘for the ends to injure the liver and send a clot of blood to the heart.’

In 1890, shortly before Chekhov’s arrival, Shternberg was induced to sign an agreement promising to cease his complaints about such treatment, on pain of being banished to the ‘most isolated corner of Sakhalin’. Having persisted, he was expelled to a tiny settlement fifty miles north. Chekhov had little to say about Viakhtu, noting only that salmon and sturgeon were caught in the nearby estuary. If Alexandrovsk was the ‘world’s end’ then Viakhtu was a space station. Miromanov said there was ‘nothing to see’ there, but he agreed to take me, as long as the road had not been washed away, and as long as I paid for fuel and vodka.

10

At 5 a.m. a dented red Land Cruiser pulled into Alexandrovsk’s main square. Before he introduced me to the man in the back, Miromanov introduced me to Suzanne, who was the car.

‘It is very important to name your vehicle.’ He patted the dashboard. ‘I knew she was called Suzanne as soon as I drove her.’

The man in the back was his friend Vladimir, the museum’s manager. He seldom spoke, but sang all the way to Viakhtu, and doled out the vodka. Both he and Miromanov had dressed in camouflage fishing overalls, in the trunk were their waders and tackle, and next to Vladimir was enough vodka to make the Red Army Choir botch its cue. They couldn’t have cared less about Shternberg.

I had looked up Viakhtu in an atlas of Sakhalin, but the modern village was not Shternberg’s. His was what Miromanov called ‘Old Viakhtu’, a mile north on the other side of an estuary, accessible only by boat. And there, on the map, I saw it: Shternberg’s ‘Russian Palestine’, a featureless plain locked between forest and water, labelled Nezhil, short for ‘uninhabited’.

It was the phase of insupportable wetness between winter and summer, when the earth is released from snow only to find itself flooded. The dead grass had the flattened look of hair that has been under a hat all day. The hares that crossed our path – a sign of bad luck, said Miromanov – were still shucking off their white winter coat. To cross the sagging wooden bridges felt like an act of fatalism. The road rolled through fishing villages whose names I knew from Chekhov: Mgachi, Tangi, Khoe, Trambaus. I was aware it was an unrepresentative time of year, transitional. Everything was a snow-dozed entropic mess, and the light was too flat to shake it into beauty.

Miromanov knew the name of none of the plants – ‘I do not know!’ – and was coldly unmoved by a sunrise that caused me to twist in my seat for a better look. His relationship with the natural world was more visceral. ‘I have been all around the world. Really, everywhere is the same – Russia, Scotland, America . . . But I could not live in any country where you must release a fish when you have caught it. Why? Why?’ He made a gun of his fingers and shot himself under the chin with a great woof of laughter.

At a fork in the road, we stopped and Vladimir divvied vodka into tin cups, and each of us opened our door and tipped the contents onto the road – libation, he said, to the Nivkh god Bordh, whose domain began there. Vladimir refilled the cups and Englishly I proffered a toast to Sakhalin (spirits make me expansive).

‘No!’ Miromanov spat. ‘Sak-ha-lin! The – hole – of – the – arse.’

Another cosmology.

11

Viakhtu – ‘New Viakhtu’ – was situated on the edge of a bank of dunes, a cluster of brightly painted timber houses around a rutted crossroads. Outside his smallholding we met Obet, the fisherman who would ferry us across the estuary to Old Viakhtu.

Obet’s camp on the sand peninsula opposite Old Viakhtu was a breaker’s yard of engine blocks and ship’s doors. An old orange bus was used as shelter, its window frames caulked with expanding foam against draughts. Welded to its undercarriage, in place of wheels, were sledge-runners made of scrolled iron drainage pipe. While we waited for the tide, I dozed inside and watched Miromanov and Vladimir casting their lines into the race.

After two hours the tide turned and Obet deemed the water deep enough. Miromanov donned a long oiled cape. The sea was violent and very cold, swimming with submerged tree trunks and branches; only afterwards, back at the camp, did I understand that it was not a journey Obet would have risked in such a small boat had I not been paying, and that the laughter of Vladimir and Miromanov had been nervous laughter. Fifteen minutes later, sodden and breathless, we pulled the boat onto a beach and climbed a low sandy cliff to the headland.

‘Nothing!’ said Miromanov, looking around.

Well, next to nothing: the raised outlines of foundations cloaked by tall dead grass; the smothered mouth of a well; a few timbers; patches of whortleberries, stunted spruce, a species of thornbush coming into bud . . . But otherwise only the dark edge of the woods bounding the plain to the north and the tarnished estuary we’d crossed to the south. A ‘lonely, abandoned grave in the empty taiga’, Shternberg called it.

As well as five houses occupied by freed convicts, a small company of soldiers had been based here, since it was a known crossing point for escaped convicts bound for Cape Pogibi. The peninsula was also, as it had been for thousands of years, a way station for semi-nomadic Nivkh. The end of the world, then, but the beginning of another. For Shternberg it was the site of his ‘ethnographic baptism’. Did he remember the advice his mother gave him, as he boarded the Petersburg back in Odessa? ‘You are a kind person, and God is just, and He exists everywhere, even on Sakhalin. He will not abandon you.’

He had only a screened corner of the soldiers’ cabin, but somehow he made a kind of home. On the wall were photos of his friends; he practised calisthenics, chopped wood, worked on his English. He read – Dante (of course) and Max Weber’s The Agrarian Sociology of Ancient Civilizations. Most importantly, he was ‘frequently visited by the sons of the taiga’. Despite his lack of any training, his research into the kinship and spiritual traditions of the Nivkh established him as a major figure in the emergent field of Russian ethnography, a discipline to which he would devote the rest of his life. During the remainder of his sentence, the authorities in Alexandrovsk, who had a strategic interest in monitoring the ‘natives’, allowed him to mount several expeditions to Nivkh settlements in the island’s north and even to the Amur delta. His 1905 monograph on The Social Organisation of the Gilyak (as the Nivkh were then known) is considered a classic, and his description of Nivkh ‘group marriage’ was eagerly championed by Friedrich Engels as supporting his and Marx’s evolutionist theory of class struggle.

‘His idealism, so full of enthusiasm, became even deeper,’ wrote a friend on meeting the freed exile (he returned to Zhitomir, under police surveillance, in 1898). ‘His rich imagination became even richer, and his faith in humankind and its bright future even more passionate than before.’ Nor were his religious or political convictions subdued. In 1907 he became director of St Petersburg’s Jewish Museum, and as late as 1921 the venerated ethnographer, aged sixty, was arrested and briefly imprisoned as a socialist agitator.

Back at the fishing camp Vladimir built a fire in the lee of the bus and hung a pot of water over it from a crook of driftwood. He added potatoes, dill, the salmon he had caught, salt, lemon juice, vodka. We sat in the bus and ate and drank. My bandage was soaked and my leg throbbed, but not unpleasantly. Back at home a week later I’d be prescribed an emergency course of rabies jabs – the one I’d had, it turned out, was for tetanus.

12

‘God’s world is good,’ Chekhov told Aleksey Suvorin when he got home to Moscow. ‘The only thing that is not good is us.’

The memory of those few weeks in 1890 became a kind of treasured wound to him. Towards the end of his life, Miromanov told me, self-exiled in Yalta for his health, Chekhov was asked why he had always been reluctant to talk about his time on Sakhalin. He paced up and down, as was his habit, and went to a window. Finally he said, ‘Afterwards, everything was Sakhalinised, through and through . . .’

He might have meant his country, the prison state it had become by 1904; but I think it more likely he was referring to the spirit of exile with which those two dark months had infected him, his sense that he had never truly come home.

Over the following days I received a series of text messages from my father. They contained no words, just emojis of flags, black flags. I thought of Shternberg’s anarchism, and of the ‘dark flag’ under which the Petersburg was said to sail. When I replied – ‘Everything okay?’ – I would receive no answer, until, the next night, in my train bunk or rehydrating noodles in some seedy hotel, I received another of those chilling semaphores from 5,000 miles away:

🏴 🏴 🏴

I took the flags as a symbol less of grief, let alone rebellion, than of negation. But it turned out that was a misreading, for those messages, from deep in the hold, marked the start of my father’s navigating a course back to the world.

13

Towards the end of May I took a train to the oil town of Nogliki, in the north-east, about 75 miles from Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky. If ‘oil town’ makes it sound booming it was not – merely a place where the offshore platforms were the main employer. From the bridge overlooking the Tym River the water was a stew of timber, whole tree trunks turning slowly in the current. The body of the river was ochre with sediment washed off the mountains; but a tributary was leaking into it the black water of the bogs. And the black was somehow cleaner than the ochre, the black of an eye’s pupil. I was reminded of something Natalia had told me, that the old Japanese name for Sakhalin translated as ‘the Island of the Black River’.

Nearby, on a lagoon, two young Nivkh men were feeding a bonfire with sheets of damp plywood. Warming herself by the fire, though it wasn’t cold, was their mother, Angela. She was fifty and wore a bright yellow Puffa jacket and large blue-framed glasses. Her family had been living in this quiet corner of the world, ten miles from Nogliki, for as long as the world has existed – before collectivisation, before colonisation. The clearing contained a large single-storey timber house, patched with sheets of wood, and adjoining sheds for firewood and fishing tackle. A track sloped through the retarded larches typical of this thin soil, to a seaweed-strewn beach cluttered with upturned wooden boats and nets beyond mending. On the horizon, like a contrail, was the mile-long spit that sheltered the lagoon from the violence of the Sea of Okhotsk and made it a sanctuary for salmon.

‘If there is no fish there is no life,’ said Angela. ‘You catch fish or you get ill. For our people it is a genetic need.’

I’d stopped here by chance but it was as if she had been expecting me. She was unsurprised by my questions, incurious. The bonfire smoke plumed and dissipated scentlessly. The peacefulness was that of a very old place settling still deeper into itself. There was no phone signal, no gas, no power.

During the purges of the 1930s as many as a third of all Nivkh men on the island were killed by the NKVD (precursor of the KGB and today’s FSB), usually on suspicion of spying for Japan. Under the USSR, the Nivkh were subjected to two phases of resettlement: first, in the 1930s, collectivisation into kolkhozes, then, in the 1960s, ukrupneniye, or ‘centralisation’ – the concentration of the kolkhozes into yet larger agricultural centres, such as Nogliki. The effect of these mandatory relocations has been to depopulate huge swathes of land. Of more than 1,000 traditional settlements scattered along the northern coast in 1962, by 1986 there were only 329. Angela’s was one of the rare families to have returned to land it occupied before collectivisation.

She herself was a poet, and we talked about the famous Nivkh writer Vladimir Sangi, master of the language and its stories, and champion of the Nivkh alphabet. He lived in Nogliki but he was ailing, too old for meetings with strange Englishmen.

On the fingers of one hand Angela counted off the speakers of Nivkh she knew, all of them women.

‘The only man who speaks the language is Sangi,’ she said. ‘We can dance like real Nivkh, we can sing and fish like real Nivkh, we can make clothes like real Nivkh. But the language we have lost, and a nation without a language is not a nation.’

The quiet of the lagoon was enlarged by a sandpiper’s flight call. In turn its flurry of stifled peeps was made to sound bleak by the vastness of the setting. Between the two, between the lagoon and the bird, there seemed to unfold a space of infinite hospitality.

Angela said, ‘We have a house in Nogliki, but genetically we cannot live there. It’s better to stay here, where it’s cold. This is our place.

Feature image © Keystone / Getty Images

All other images courtesy of the author