It’s not just the sentences – though me-o-my, the sentences! – it’s the sensibility. When poets turn their hands to prose, those hands might well belong to Midas. In the best of these novels, poetry’s philosophy, acuity and truth-seeking are carried over into the prose.

I grew up reading poetry and plays because that’s what was in the house. Once I’d become accustomed to density and concision, the novel seemed a baggy, watery, laborious, unapproachable thing. Nancy Drew was intimidating. The Hobbit was a lumbering, heaving giant. Yevtushenko – conversely – was slim, lithe, safe and succinct. There was space on the page for the reader. He spoke directly to me, a small, trusted audience. He didn’t ask me to remember any details, nor did he play tricks or engineer twists. Everything included was essential. Concentrated. Neither that chair nor this reader could be done without. Each moment was self-contained, earnest, self-supporting.

As the years went by, I found my way into the novel form, first as a reader, and later as a writer. I began to see that the distance between the two forms doesn’t need to be vast, and sometimes it isn’t – it was a matter of finding the right novels. A novelist can share a poet’s sensibility, precision, generosity, slant, view, broodiness, relationship with language, imagery, metaphor and the visual. But what about the novelists who are poets? Do their novels betray them as such? If so, how? I began to compile a list of my favourite contemporary novels by poets. To my eye, all expose their authors as poets, but this is no failing. Quite the opposite.

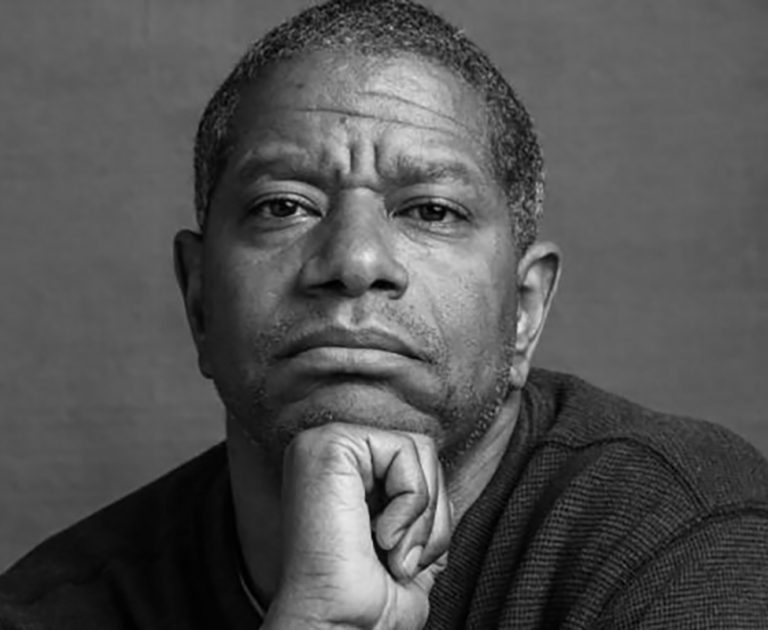

When the Man Booker Prize first opened to American authors in 2016, I was decidedly in the peeved camp. Until The Sellout became the first American-authored winner that same year. Then, I was delighted. Of all the Booker contenders I’ve read, The Sellout is my favourite. Every sentence is a masterpiece. The prose is dense and wise, cerebral and uproarious, and I have never read anything like it. It’s about race relations, community, empathy and the tortured American spirit. It admits the reader into a worldview and a society she has never before seen on the page. Someone once said comedy is tragedy plus time – this book is five minutes away from splitting the reader’s sides open like an Easter egg. The clock is stuck though, in America, and while this reads like satire, tragedy reigns.

An unforgettable, startling, haunting novel, Owls Do Cry follows Daphne Withers – recently bereaved of her sister – to the ‘the Dead Room’ of a mental asylum in 1930s New Zealand. The novel is informed by Frame’s own time spent incarcerated, where she survived much-documented horrors and brutalities. Astoundingly, she was scheduled to have a lobotomy, but the procedure was hastily cancelled when her first book won a prestigious literary prize. Even the memory of this book can make me weep. It is a prose poem of the highest order.

Miller’s singular Forward Prize-winning book of poetry, The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion, is a dialogue between a Rastaman and a cartographer attempting to map a way to the eternal city of Zion. The Rastaman helps him to fathom place anew. Augustown carries on with this exploration of place. It is – as Laura Miller’s New Yorker review calls it – ‘a village novel’, with many stories and characters correlating with one another, just as folklore does with fact. It is an unusual, ambitious and atmospheric novel that invites the reader into a haunted, compassionate community.

In the New Yorker, Laura Miller describes the stereotypical ‘poet’s novel’ as being ‘introspective, replete with long passages of description, and scant of plot’. If these are the criteria of a poet’s novel, then Murdoch’s Man Booker Prize-winning The Sea, The Sea conforms to stereotype. A retired actor moves to a home by the ocean in order to look at the water, to read, eat, write a memoir and to be alone. Doesn’t sound like much? Consider it, then, as a book of philosophy. You’ll find yourself laughing with and caring for the characters. Among many many things, this remarkably intelligent and moving novel is about who we think we are versus who we are. A poet versus a novelist? Murdoch is both.

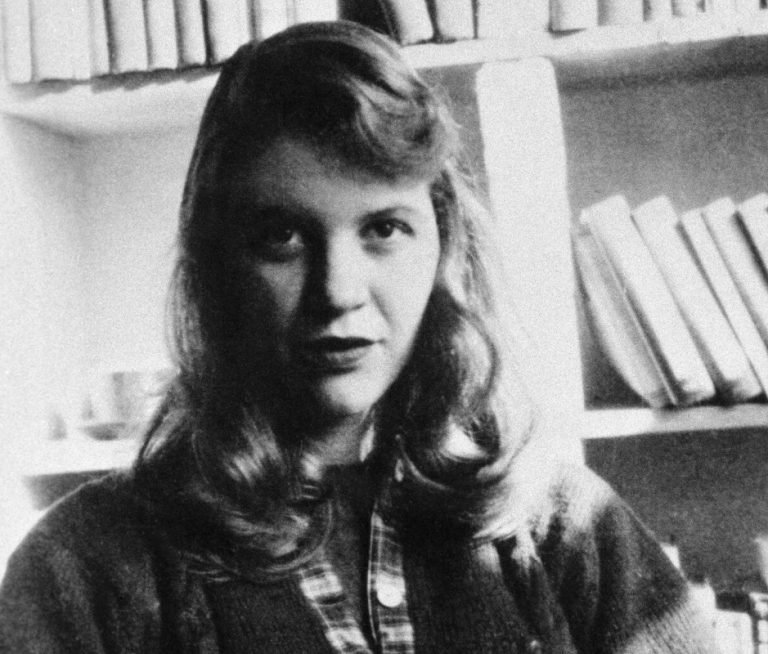

In both her poetry and her prose, Plath’s voice is as distinctive as Emily Dickinson’s. From her syntax to her imagery, from the urgency of her narration to the inebriation her descriptions inflict, the atmosphere of this book is a motorcycle helmet the reader puts on. While the pressure is reassuring, the world outside the helmet begins to seem distant, less real, less compelling and intelligible, certainly less tolerable. The Bell Jar is a journey into the mind. A poet is at the helm. It is a dangerous novel to face up to. It’s even more dangerous not to.

This novel about a poet on a fellowship in Madrid in 2004 could only have been written by a poet. It is a hilarious, self-aware künstlerroman that’s stylistically looser, and structurally and linguistically more relaxed, than Lerner’s later novel 10:04. With space limitations in mind, let me quote just one exemplary sentence:

‘But my research had taught me that the tissue of contradictions that was my personality was itself, at best, a poem, where “poem” is understood as referring to a failure of language to be equal to the possibilities it figures; only then could my fraudulence be a project and not merely a pathology; only then could my distance from myself be redescribed as critical, aesthetic, as opposed to a side effect of what experts might call my substance problem, felicitous phrase, the origins of which lay not in my desire to evade reality, but in my desire to have a chemical excuse for reality’s unavailability.’

Nobel Prize-winner Günter Grass said that he wasn’t able to choose the subject matter of this book. It was already chosen for him. He says that a writer must admit that if he does not want history to repeat itself, then he must open his mouth. For Grass, this meant writing about the rise of Nazism. What comes out is a torrent – an immersive, persuasive, captivating and frenetic voice relating what must be related. At times brutal and deeply discomfiting, at times farcical and surreal, this witty, canny, uncanny novel is as necessary now as it was when it was published in 1959. In his own life, this novel’s trickster narrator prefers to bang a tin drum rather than to speak. Thankfully, we readers are privy to all that he doesn’t vocalize, rendered in Grass’s paragraph-long sentences, rhythmic and photographically detailed, and we hear the novel speak through its powerful imagery, allegory and symbolism about survival, guilt, civic responsibility and the feeblegrasp we as individuals and as communities have on our sanity.

Levy’s fiction is steeped in modernist influence. Traces of Ezra Pound, H.D., Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and T.S. Eliot are evident to the reader, despite how immediately contemporary Hot Milk is. The story takes off on an EasyJet flight to Southern Spain that’s undergoing extreme turbulence. A passenger begins to come out in a rash, introducing the novel’s main subject matter: hypochondria. But hypochondria is only a symptom of this story; not the cause. The cause has to do with sorrow; a disconnection from the self; with who one is or wants to be; with what we owe our loved ones; how we can and cannot help ourselves, let alone anyone else. It’s a bravely intimate, allusion-rich, sensorially abundant novel. The dialogue is testament to Levy’s skills as a playwright; its symbolism, sentences, and its characters’ internal lives, to her skills as a poet.

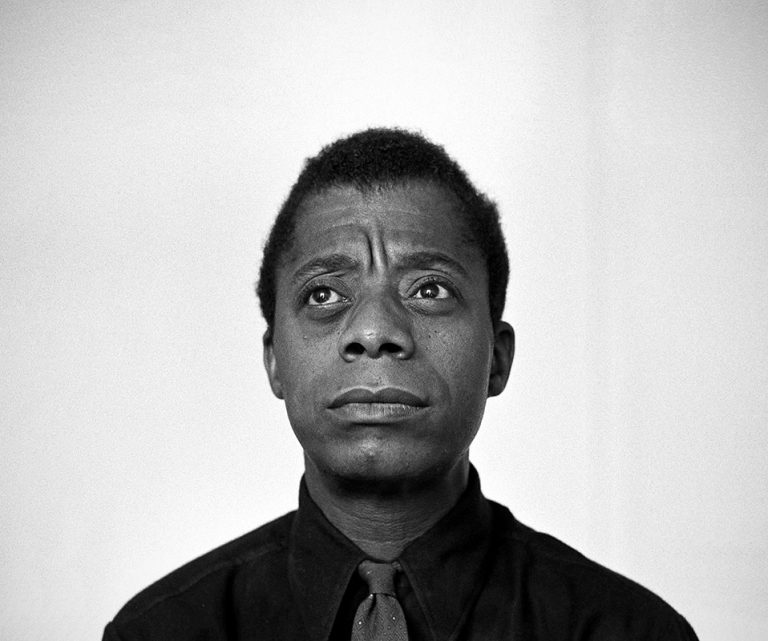

Set in Paris in the 1950s, this novel explores love, desire, and a sexual identity contending with convention’s deadly resolve. Baldwin renders atmosphere and character effortlessly in flowing, natural prose – at times deceptively urbane and relaxed for the environment it considers. The dialogue is where this novel betrays its author for a poet:

‘I began to feel that I’d, somewhere, missed the boat . . . You know the boat I’m talking about. They make movies about it where I come from. It’s the boat that, when you miss it, it’s a boat, but when it comes in, it’s a ship.’

One more example, and I rest my case:

‘“Anyway,” he said mildly, “I don’t see what you can do with little fish except eat them. What else are they good for?”

“In my country,” I said, feeling a subtle war within me as I said it, “the little fish seem to have gotten together and are nibbling at the body of the whale.”

“That will not make them whales,” said Giovanni. “The only result of all that nibbling will be that there will no longer be any grandeur anywhere, not even at the bottom of the sea.”

“Is that what you have against us? That we’re not grand?”’

With this haunting, mermerizing, myth-rich, culture-dizzy, spell-prosed novel of astonishing scope and witness, Keri Hulme was the first New Zealander to win the Man Booker Prize. That each page is so damn good (original, authoritative, timeless, alert, dreamy, earthy, metaphysical) makes its length overwhelming. Having lived in New Zealand for seven years, this book encapsulates one world within that multitudinous country like nothing else I’ve read. The complexity of landscape, of isolation’s luxury and oppression, the postcolonial stamp on the place bearing the bust of a monarch few care to name or recognize; the Māori, Polynesian, Celtic and Pākehā identities and pathologies – shoulder to shoulder, and even nose to nose, but far from hand in hand. This book is more prescient now than ever, given that our historical moment is grappling with issues of patriotism, tradition, co-existence, and tolerance, and the onus is on all of us – poets and politicians and the people too – to speak out.

Caoilinn Hughes’s debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp, is available now.