He is the War Correspondent, she is the Transgressive Novelist. They have been flown in for the summit on Genocide(S). She spots him at the airport baggage claim and nods in the direction of a student holding up a legal pad with his name written on it in heavy black marker – misspelled.

‘Want to share my ride?’ he asks.

Caught off guard, she shakes her head no.

She doesn’t want anyone picking her up, doesn’t want the obligation to entertain the young student/fan/retired teacher/part-time real-estate broker for the forty-five minutes it takes to get where they’re going.

Every time she says yes to these things – conferences, readings, guest lectures – it’s because she hasn’t learned to say no. And she has the misguided fantasy that time away from home will allow her to think, to get something done. She has brought work with her: the short story she can’t crack, the novel she’s supposed to finish, the friend’s book that needs a blurb, last Sunday’s newspaper . . .

‘Nice to see you,’ the man at the car-rental place says, even though they’ve never met. He gives her the keys to a car with New Hampshire plates, live free or die. She drives north toward the small college town where experts in torture politics, murder, along with neuroscientists, academics, survivors, and a few ‘special guests’ will convene in what’s become an ongoing attempt to make sense of it all, as though such a thing were possible.

The town has climbed out of a depression by branding itself, ‘America’s Hometown’. Flags fly from the lampposts. Signs announce the autumn harvest celebration, a film festival, and a chamber-music series at the Presbyterian church.

She parks behind the conference center and slips in through the employee entrance and down the long hall to a door marked this way to lobby.

On the wall is a full-length mirror with a handwritten message on the glass: check your smile and ask yourself, am i ready to serve?

The War Correspondent comes through the hotel’s front door at the same time as she slides in through the unmarked door by the registration desk.

‘Funny seeing you here,’ he says.

‘Is it?’

He stands at the reception desk. The thick curls that he long ago kept short are receding; in compensation they’re longer and more unruly.

He makes her uncomfortable, uncharacteristically shy.

She wonders how he looks so good. She glances down. Her linen blouse is heavily wrinkled, while his shirt is barely creased.

The receptionist hands him an important-looking envelope from FedEx.

She’s given a heavily taped brown box and a copy of the conference schedule.

‘What did you get?’ she asks as he’s opening the FedEx.

‘Galleys of a magazine piece,’ he says. ‘You?’

She shakes the box. ‘Cracker Jacks?’

He laughs.

She glances down at the schedule. ‘We’re back-to-back at the opening ceremonies.’

‘What time is the first event?’

‘Twelve thirty.’ She thinks of these things as marathons; pacing is everything. ‘You’ve got an hour.’

‘I was hoping to take a shower,’ he says.

‘Your room’s not quite ready,’ the receptionist tells him.

‘Did you fly in from a war zone?’ she asks.

‘Washington,’ he says. ‘There was a Press Club dinner last night, and I was in Geneva the day before, and before that the war.’

‘Quite a slide from there to here,’ she says.

‘Not really,’ he says. ‘No matter how nice the china, it’s still a rubber chicken.’

The receptionist clicks the keys until she locates a room that’s ready. ‘I found you a lovely room. You’ll be very happy.’ She hands him the key card. ‘You’re both on the executive floor.’

‘Dibs on the cheese cubes,’ he says.

She knew him long ago before either of them had become anyone. They were part of a group, fresh out of college, working in publishing, that met regularly at a bar. He was deeply serious, a permanently furrowed brow, and he was married – that was the funny thing, and they all talked about it behind his back. Who was married at twenty-three? No one ever saw the wife – that’s what they called her. Even now she doesn’t know the woman’s name.

An older man approaches the War Correspondent. ‘Very big fan,’ the man says, resting his hand on the Correspondent’s shoulder. ‘I have a story for you about a trip my wife and I went on.’ He pauses, clears his throat. ‘We were in Germany and decided to visit the camps. When we got to our hotel, I asked, “How do we get there?” They tell us take a train and then a bus, and when you arrive, there will be someone there to lead you. We go, it’s terrifying; all I can think of as the train goes clackety-clack is that these are the same rails that took my family away. We get to the camp, there’s a cafe and a bookstore selling postcards – we don’t know what to think. And when we get back to the hotel, the young German girl at the front desk looks at us with a big smile and says, “Did you enjoy your visit to Dachau?” Do we laugh or cry?’ The man pauses. ‘So what do you think?’

The War Correspondent nods. ‘It’s hard to know, isn’t it?’

‘We did both,’ the man says. ‘We laughed, we cried, and we’re never going back.’

The Correspondent catches her eye and smiles. There are delightful creases by his eyes that weren’t there years ago.

She’s annoyed. Why is his smile so quick, so perfect?

As she moves toward the elevator, a conference volunteer catches her arm. ‘Don’t forget your welcome bag.’ The volunteer hands her a canvas tote, laden with genocide swag.

She goes straight to her room, puts the do not disturb sign on the door, and locks it. What is his room like? Is it the same size, one window overlooking the parking lot? Or is it bigger? Is it a suite with an ocean view? They’re hundreds of miles from the sea. Is there a hierarchy to Genocide(S) housing?

‘Do you ever go off-duty?’ she hears her therapist’s voice asking.

Not really.

She unpacks the welcome bag: a coffee mug from the local college, a notepad and pen from a famous card company – when you can’t find words, let us speak for you – and a huge bar of chocolate from a pharmaceutical company that makes a popular antidepressant. The wrapper reads sometimes getting happy should be simple.

She thinks of her therapist. She has the opposite of transference – she never wishes the therapist were her mother or her lover. She thinks of the therapist and is relieved not to be married or related to her. A decision as small as trying to decide where to go for dinner or what to eat would take hours of negotiation and processing. Eventually she would cave in and do whatever she had to to make it stop. She secretly thinks the therapist is a passive-aggressive bully and perhaps should have been a lawyer.

‘You wrote an exceptionally strong book illustrating the multi-generational effects of Holocaust trauma. You knew there would be questions.’ She hears the therapist’s voice loud and clear in her head.

‘It’s a novel. I made it up.’

‘You created the characters, but the emotional truths are very real. There are different kinds of knowing.’

Silence.

‘You spent years inhabiting the experience on every level – remember when you starved yourself ? When you drank tainted water? When you didn’t bathe for thirty days?’

‘Yes, but I was not in the Holocaust. I am an impostor – the critics made that quite clear.’

The therapist clucks and shakes her head.

The Novelist wonders, aren’t therapists trained not to cluck?

‘Critics aren’t the same as readers, and your readers felt you gave language and illumination to a very difficult aspect of their experience. And you won an international award.’ The therapist pauses. ‘I find it interesting that you have to do this.’

‘Do what?’

‘Undermine yourself.’

‘Because I’m better at it than anyone?’ She glances up, smiling.

The therapist has the sad face on.

‘At least I’m honest,’ she says.

Still the sad face.

‘Really?’ she asks.

‘Really,’ the therapist says.

She said yes to the Genocide(S) conference after having made a pact with herself to say no to everything, a move toward getting back to work on a new book. She’d spent the better part of a year on a book tour, traveling the world giving readings, doing interviews, answering questions that felt like interrogations. It was as if the journalists thought that by asking often enough and in enough languages, eventually something would fall out, some admission, some other story – but in fact there was nothing more. She’d put it all in the book.

In the hotel-room mirror, she takes a look at herself. ‘Check your smile and ask yourself, Am I ready to serve?’

She blushes. She was thinking about him – the War Correspondent.

Her phone rings.

‘Are you there yet?’ Lisa asks. ‘I wanted to make sure you arrived safely.’

‘I’m fine,’ she says.

‘Did you get the box?’

‘I think so,’ she says.

‘Did you open it?’

‘No.’

‘Well, go ahead.’

She doesn’t open the box, just the note on top: Sorry we fought. Here’s making it up to you . . .

‘But we didn’t fight,’ she says.

‘I know, but we usually do, and I had to order it ten days in advance,’ Lisa says.

‘You could have tried a little harder,’ she says.

‘What do you mean?’ Lisa says. ‘I planned the whole thing weeks ago.’

‘I mean you could have at least picked the fight if you knew you’d already sent a make-up gift,’ she says.

‘I don’t get you,’ Lisa says. ‘I really don’t.’

‘I’m joking. You’re taking it way too literally.’

‘Now you’re criticizing me?’

‘Never mind,’ she says. ‘Thank you. You know I love chocolate.’

‘Indeed I do,’ Lisa says, not realizing that the Novelist hasn’t even opened the box.

She knows Lisa well enough to know exactly what’s in the box. Instead she opens the chocolate bar sponsored by the antidepressant manufacturer and takes a big bite. The thick sound of chocolate being chewed fills air.

‘That’s more like it,’ Lisa says.

‘I have to go,’ she says. ‘I’m just getting to the check-in desk.’ She looks at herself in the mirror; can Lisa tell when she’s lying?

‘What is going on with you?’ Lisa says. ‘I can’t read you.’

‘Ignore me,’ she says. ‘I’m lost in thought.’

‘I’ll find you later,’ Lisa says, hanging up.

The welcome lunch is served: cold salads like the sisterhood lunch after a bar mitzvah, a trio of scoops, egg salad, tuna salad, potato salad, a roll and butter, coffee or tea.

She is seated at the head table among the academics with university appointments in the fields of trauma and tragedy. The War Correspondent is two seats down.

The man she wants to meet, Otto Hauser, the ephemerologist, is missing. His seat is empty. His plate is marked vegan.

‘Has anyone seen Otto Hauser?’ she asks repeatedly. She has been obsessed with Otto Hauser for years, having read the only two interviews he’s ever given and seen a glimpse of him in a documentary. She heard later that he asked to have himself taken out of the picture.

Finally someone tells her that Otto has been delayed; there was a fire in his warehouse near Munich.

The conference leader, himself the victim of a violent attack that left him with only half a tongue, calls the room to order. It is difficult to understand what he’s saying. She finds herself looking for clues from the deaf interpreter on the far side of the stage.

‘This year’s program, From Genocide(S) to Generosity: Toward a New Understanding, brings together diverse communities, including but not limited to Cambodia, East Timor, Rwanda, the Sudan, the former Yugoslavia, the Holocaust of World War II, the history of colonial genocides, and the early response to the Aids epidemic. And this weekend we ask the important question: Why? Why do Genocide(S) continue to happen?’

He goes on to thank their sponsors, an airline, two global search engines, an insurance firm, the already mentioned antidepressant manufacturer, and a family-owned ice-cream company.

Before turning the microphone over to a fellow board member, he says, ‘The cash bar in the Broadway Suite will be open until midnight and serving complimentary fresh juices donated by Be My Squeeze, and this year we have a spiritual recharge room for meditation or prayer with the bonus of a free chair massage brought to us by Watch Your Back.’

Following the conference leader’s welcome, the chair of the local English department does the honors, introducing her. The chair’s words are passionate and strange, a simultaneous celebration and denigration of her, both personally and professionally. All in the same breath, the chair mentions the author’s being known for her lusciously thick dark hair, that she won France’s Nyssen Prize for International Literature, and what a shock it was to her that the book had sold so many copies.

The War Correspondent leans across and whispers loudly over heads, ‘I think she wants to fuck you.’

‘I feel like she just did,’ she whispers back before standing and taking the microphone briefly. ‘Thank you, Professor,’ she says, intentionally calling the woman ‘Professor’ rather than ‘Chair’. ‘You clearly know more about me than I know about myself.’

There is laughter in the house.

The War Correspondent is introduced by the college’s football coach. ‘When Dirt and Blood Mix is Eric Bitterberg’s very personal story of being on the front lines with his best friend from high school, a US Army sergeant.’

‘Is it Biter-berg or Bitter-berg?’ she whispers loudly in his direction.

‘Depends on my mood,’ he says.

The afternoon session immediately follows lunch. While others go off to sessions such as Australia’s Stolen Generations and The Killing Fields Revisited, she heads toward the Americas Suite for her first panel, Where I’m Calling From: Modern Germany and Related His/Her Stories.

Her fellow panelists include a young German scholar who, despite being fluent in English insists on speaking in German, and Gerda Hoff, an elderly local woman who survived the camps and more recently cancer and has now written a memoir, called Living to Live.

‘You look different than the photo on your book,’ the moderator says as she sits down – it’s not a compliment.

And then, without a beat, the moderator begins: ‘Germany and family history – where was your family during the Holocaust?’

The German panelist says that his grandparents were in the food business and struggled.

‘They were butchers,’ the moderator says; it’s not a question but a statement.

‘Yes,’ the German confirms, and declines to say more.

The survivor says her father was a teacher and her mother was a woman known for her beautiful voice. She and her siblings watched as her parents were shot in the back and fell into large open graves. She is the only one still alive; her sisters died in the camps, and two years ago her brother jumped in front of a train.

‘And you?’

The Novelist would like to buy a vowel. She’d like to pass, to simply evaporate, or at least have someone explain that clearly there was an error in putting these panels together, because she doesn’t belong here.

She draws a breath and allows for the weight of the air to settle before she explains: Her family wasn’t from Germany but rather Latvia. They arrived in America before the war, and were dairy farmers in New England.

It’s like she’s on a quiz show with points awarded for the most authentic answer. She’s plainly the loser.

She scans the audience. There are no young people. It reminds her of the classical concerts her parents used to take her to; no matter how old she got, she was always the youngest one.

The moderator carries on. At some point, while her mind is elsewhere, the conversation turns back to her, with the question, ‘Is there such a thing as Holocaust fiction? Are there experiences where the facts of history are already so challenged that we dare not fictionalize them?’

She takes a moment, then leans forward in her chair, drawing the microphone close, unnecessary considering the size of the room. This is the question asked around the world, the moment they’ve all been waiting for.

‘Yes,’ she says definitively, and then pauses. ‘Yes, there is such a thing as Holocaust fiction. It’s not something I invented. There are many novels that are set during or relate to the Holocaust, including books by Elie Wiesel, Thomas Keneally, Bernhard Schlink, and so on. With regard to the question “Are some subjects so historically sensitive that we shouldn’t touch them in fiction?” I’d say the purpose of fiction is to illustrate and illuminate. We see ourselves more clearly through the stories we tell.’

‘But what is your relation to the Holocaust?’ the moderator drills down.

‘I am a Jew, my grandfather’s brothers died in the camps.’

‘What does it mean to you to be a transgressive woman who writes books that are intentionally shocking?’

‘ “Transgressive” is a word you use to describe me; it’s what you label me to make me other than you. The very history we are here to discuss reminds us of the danger of labels and separating people into categories.’

Throughout the audience there are murmurs of approval. Despite the fact that these panels are supposed to be conversations, they are actually competitions, judged by the audience. ‘As for the question regarding an intention to shock, I have written nothing that didn’t first appear in the morning paper,’ she says, aware that she’s got a week-old paper in her bag right now. ‘What is truly shocking is how little we do to prevent these things from happening again and –’

‘Fiction is a luxury our families didn’t have,’ Gerda Hoff cuts her off. ‘We didn’t pack our summer reading and go off to the camps, happy, happy. This isn’t even your story. What right do you have to be telling it? It is insulting. I am one little old lady, but I am here representing six million Jews who cannot speak for themselves.’

The audience applauds. Score for Gerda Hoff!

She’s tempted to quote her mother’s frequent comment – ‘Well, you’re entitled to your opinion’ – but she doesn’t. Instead she says, ‘And that is exactly why I wrote my book: to describe the impact of those six million lives on the subsequent generations. I wrote this book so that those of us who weren’t there, those of us who were not yet born, would better understand the experience of those who were present. And,’ she says, ‘and prevent it from happening again. Never Again.’

‘So it’s all a big lie?’ the old woman says.

‘You show no love for Germany,’ the German scholar says, clearly feeling left out of the debate.

‘My novel is not about Germany. It is the story of four generations of a family struggling to claim their history and their identity.’

The panel ends, and even though the members of the audience don’t hold up scorecards, she can tell that Gerda came in first, she was second, and the German a distant third.

Never again, she tells herself. Never say yes when you mean to say no.

After the panel she sits at a small table signing books and answering questions.

‘Are you a gay?’ an old woman whispers, in the same voice her mother would ask, Are they Jewish? ‘I think you’re a gay? My son, I think he’s also a gay. He doesn’t tell me, but a mother knows.’

When the line is gone, she buys a copy of her own book and gives it to Gerda Hoff as Gerda is leaving.

‘I don’t want it,’ Gerda says.

‘It’s a gift. I think you might find it interesting.’

‘I’m eighty-three years old. I watched my parents shot in the back. I buried my own children, and now I’m dying of cancer. I didn’t live this long to be polite about a piece of dreck that you think I might “like”.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she says.

Gerda leans toward her, ‘You want to know what I like? Chocolate ice cream. That’s something to live for. Your book, a shaynem dank dir im pupik. I lived it, I don’t have to read it,’ she says, and then toddles off down the hall.

She finds the War Correspondent by the elevator – waiting.

‘How’d it go?’ he asks.

‘Eviscerated,’ she says.

‘I wouldn’t take it so personally.’ They step in, and he hits the button for the fourth floor.

‘They may be senior citizens, but they’re pugilists,’ she says. ‘They’re not just taking Zumba, they’re also boxing, and they know where to punch. What about you?’

She looks at him; the top two buttons of his shirt are open, dark hair spinning out from between the buttons. She has the urge to pluck a hair from his chest like it was a magical whisker.

‘Apart from the heckler who called me a pussy, it was okay.’

The elevator opens on the executive floor. ‘So I’ll see you at the cocktails?’ she says, stepping out.

‘Not for me. I’m on deadline.’ He pauses. ‘I don’t think I’ve seen you in years except at the book awards. Congratulations, by the way. Your book is the kind of thing I could never do,’ he says as he starts down the hall.

‘In what way?’ she calls after him.

‘Fiction,’ he says, turning back toward her. ‘I could never make it up. I have no imagination.’

She smiles. ‘I’m not quite sure what you mean, but for now I’ll take that as a compliment.’

‘Drink later?’

She nods. ‘In my head I keep calling you the War Correspondent. Years ago I used to call you Erike, but somehow that no longer fits.’

‘You called me Erike because that’s what my mother used to call me.’

‘You were married. We were all impressed; it seemed very grown-up. We talked about you behind your back.’

‘That’s funny,’ he says.

‘Why?’

‘I was miserable.’

‘Oh,’ she says.

‘I thought I was so smart, had it all figured out.’ He shrugs.

‘And why did we hang out there, at the Cedar Bar?’ she asks. ‘Who did we think we were? Painters?’

‘Up and coming,’ he says. ‘We thought we were going someplace.’

‘And here we are.’

There’s an awkward beat. ‘So what are you going to do now? I remember that you used to ride your bike everywhere. You never went on the subway.’

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘I used to ride my bike everywhere – until I blew out my knee.’

‘Do you remember that I got you to go on the subway?’

‘I do,’ she says, smiling. ‘It was January.’

‘The seventeenth of January, 1991, the night the bombing started in Baghdad.’

She nods, surprised he remembers.

‘I made you take the subway all the way uptown.’

‘It was a big night,’ she says.

‘Yep,’ he says, and then seems lost in thought. There’s a silence, longer than feels comfortable. ‘All right, then,’ he says, and abruptly heads down the hall, leaving her to wonder – did something happen?

She goes to her room and sits to meditate. Her meditation is punctuated by thinking about him. She keeps bringing herself back to her body, to the breathing and counting, until she falls deeply asleep. She has horrible dreams and wakes up forty minutes later, sweaty and confused as if roused from general anesthesia. She has no idea where she is and is trying to process whether anything in the dream was real.

The antidote – calling her mother.

‘What are you doing?’ her mother asks, her tone an instant reality check.

‘I just took a nap. It was awful, nightmares,’ she says. ‘I’m away at the conference.’

‘What is this one about?’

‘Genocide(S). I accepted the invitation thinking of you.’

‘Why me? I wasn’t killed in a genocide.’

‘Because of the Holocaust, because of Pop-Pop’s brothers.’

‘Oh, that was very nice of you,’ her mother says.

‘It’s not about being nice,’ she says, ‘it’s about remembering.’

‘It’s good you remember,’ her mother says. ‘I completely forgot you were going away. When are you coming home?’

‘Sunday night?’

‘And when are you coming to see me?’

‘Maybe next weekend.’

‘Next weekend isn’t good. I have theater tickets.’

‘Okay, then maybe the following.’

‘It would be nice if you could come sooner. Come during the week. I’m not so busy then.’

‘I work during the week.’

‘Is that what you call creative writing – work?’

‘Yes.’

‘When my friends say they love what you do, I say they’re entitled to their opinion.’

‘Thanks, Ma, I’m glad that I work so hard only to have it embarrass you.’ She takes out her computer, puts her mother on speaker.

‘Are you typing now while you’re talking to me?’

‘Yes.’

‘I hope you’re not writing down what I’m saying.’

‘No, Mom, I’m looking up synagogues and texting one of the conference organizers to ask if tonight’s dinner is seated.’

‘I’m a private person. I don’t need the world to know so much about me.’

‘But, Mom, the book isn’t about you.’

‘That’s what you say, but I know better. So when are you coming to visit me?’

‘I have to go, Ma. I love you. I’ll call you tomorrow.’

The agitation of talking with her mother has prompted her to get up, wash her face, unzip her suitcase, and contemplate what to wear. There’s a full-length mirror mounted to the wall. She looks different than she remembers, shorter, rounder. It’s happening already – the shrinking?

Lisa texts, ‘Are you dead? It’s unlike you not to call or write.’

What’s the problem? she asks herself. Is the problem Lisa? Or is it something else?

‘We talked just two hours ago. Meanwhile, I had the pink one,’ she writes back. It started as a joke when they were newly a couple and has become a recurring theme. ‘I sucked it. The chocolate melted in my mouth,’ she texts.

‘Lol, not on your hands,’ Lisa writes.

She dresses for temple, simple black pants and a shirt. On her way out of the building, she passes the ‘gathering’. They don’t call it a cocktail party because that sounds too festive, and between those who don’t drink for religious reasons, those who are in AA, and those whose blood thinners or pain medications interact badly, the ‘Freedom and Unity’ mocktail is doing a brisk business.

One of the organizers spots her and insists she mingle. Mingling, she searches for Otto Hauser, who has still not arrived. She’s introduced to Dorit Berwin, a Brit, who rescued hundreds of children from certain death in the Sudan. Dorit personally adopted fifty-four children and would have taken more, but her biological children made a show of distancing themselves from her with a public campaign titled ‘They’re Kids, Not Kittens’.

She finds it odd that it is Friday night and none of the conferees at the gathering seem to notice that it’s Shabbos.

Around the world it is her habit to go to temple; she’s the only one in her family who practices.

‘What do you mean, practices?’ her mother says. ‘We’re Jewish, what are we practicing for? Haven’t we been through enough?’

‘It makes me feel I’m part of history.’

As she drives over the hills on a two-lane country road, the sun is dropping low on the horizon. There are cows making their way home across fields and self-serve farm stands with fresh eggs, tomatoes, cut flowers, and free zucchini with every purchase. The sky is a glorious and deepening blue.

It’s just past sunset when she pulls in to the tiny town. The raised wooden Star of David and the mezuzah are the only outward markers on the old narrow building. She knocks three times on the heavy wooden door, like a character in an Edgar Allan Poe story. She knocks again, she waits, she knocks once more, and finally . . .

‘Can I help you?’ a man asks through the door.

‘I’m here for Friday-night services,’ she says.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Am I late?’

‘A little.’

‘Can I come in?’

‘I guess so,’ the man says, opening the door. ‘We have to be careful. You never know who’s knocking.’

The synagogue is small and lost to time. There are about thirty people between her and the rabbi.

‘What is it to be a Jew?’ the rabbi is demanding of the group. ‘Has it changed over time? We are reminded of our forebears, who were not free, who had to say yes when they meant no. We are all transgressors, exiles; there is none among us who has not sinned. It is not about the size of one’s sin or one sin being greater than another – but that we are all human and thus flawed, and only by recognizing those flaws can we come to know ourselves.’

She listens, a stranger in the rear of the room, looking at the backs of heads, contemplating. Would Lisa go to temple with her? She’s never asked, because she and Lisa are forever in a push-pull needing space, room, time. Lisa says they’re together so much that it’s hard to know where one ends and the other begins. But she always knows where she ends – she ends before she begins. She’s not what she calls a ‘classic lesbian’, a merger, who brings the U-Haul on a second date. She is perpetually frustrated and disappointed. She wonders, is it a Jewish thing, a relationship thing, or is it just her?

The sound of a crying baby brings her back into the moment. As the woman with the crying infant leaves, she notices that he is there, up front. She recognizes him from his hair, the nape of his neck. He is four rows up and deep into it, dipping his head at key points.

Surprised but pleased, she used to think of him as serious but thought that his success had eroded that. She imagines him now as a bit more of a wartime playboy, hanging out with people like the fearless woman journalist with the eye patch who was killed in Syria. She imagines he plays high-stakes poker and has drunken late-night sex with exotic women who speak no English.

‘Those saying the Mourners’ Kaddish, please stand,’ the rabbi intones. He stands, prays. She can tell from the rise and fall of his shoulders that he begins to cry.

And then it is over. The Shabbos has begun, and the congregation is invited to stay for a piece of challah and a sip of wine – in tiny plastic cups like thimbles.

‘I didn’t know you were Jewish,’ he says, tossing back the tiny cup like it was a dose of cough medicine. ‘I thought you were gay.’

‘Like they’re related, Jew and gay? Different categories. I thought you were married.’

‘Divorced, but I am living with someone.’

‘So am I,’ she says. ‘See, I knew we had something in common. What about the deadline?’

He shrugs.

‘How did you get here?’

‘Taxi. Thirty dollars. Do you know that the taxis are shared? You pick up people along the way – a toothless woman and groceries, a fat man who couldn’t walk any farther.’

‘Do you go to temple a lot?’ she asks.

‘No,’ he says, wiping a tear from his eye.

She pretends not to notice.

‘I’m starving,’ he says. ‘The last thing I ate was the death tuna at lunch. Do you think there’s Chinese around here? In my family that’s the way we do it, temple and then hot-and-sour soup.’

She shakes her head. ‘No but there’s a famous ice-cream place near here, wins all the prizes at the state fair.’

The ice-cream stand is set back from the road in the middle of nowhere. They find it only because a long line of cars, trucks, minivans is pulled off and parked in the dirt.

we make our own because we like it that way is written in bubble-lettered Magic Marker on poster board. The long summer season has taken a toll; thundershowers and ice-cream drips have caused the letters to run. The posters look like they’ve had a good cry.

Enormously large people lower themselves out of their minivans and wobble toward the stand.

‘What I like about these gigs is the local color,’ he says, taking it in.

A few late bees hover.

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘It can be really hard to get out of one’s own circle.’

‘I’ll go for the medium Autumn Trio,’ the War Correspondent tells the boy behind the counter.

‘Small chocolate in a cup,’ she says.

The War Correspondent pays.

‘Chivalrous.’

‘Taxi fare.’

The ice-cream scoops are like a child’s fantasy of what an ice-cream cone might be, the scale both magical and upsetting.

‘This is what’s wrong with America,’ he says, digging in.

‘Entirely,’ she says.

They sit at a picnic table in a grove of picnic tables.

‘Was your family religious?’ he asks between licks.

‘No,’ she says. ‘Yours?’

‘My grandmother and my aunts are observant, but not my father, who adamantly refuses.’

‘Where were they from?’

‘From a town that no longer exists.’

‘Mine came in a pickle barrel,’ she says. ‘When I think about it, I imagine the ocean filled with floating pickle barrels all the way from Latvia to Ellis Island.’

He’s like a kid eating his ice cream, happier with each lick. She reaches over and wipes drips off his chin. He smiles and keeps licking. He has three flavors, the house special: butter pecan, maple walnut, brandied coffee.

‘Taste it?’

She takes a lick, eyes closed. ‘Maple,’ she says.

‘Try over here,’ he says, turning the cone.

‘Brandy,’ she says. She slips a spoonful of hers into his mouth, noting that there is an immediacy to ice cream, that it travels through you, cold down the middle while the flavor stays on your tongue.

‘A shtick naches,’ he says.

‘Naches.’ She laughs. ‘My grandmother used to say that when she brushed my hair. She pulled so hard that for years I thought naches meant “knotty hair”.’

‘It means “great joy”.’

‘A yiddisher kop,’ she says. ‘Mr Smarty Pants.’

She has another lick of his ice cream, and then there’s a pause, a moment, realization.

‘You okay?’ he asks.

‘The ice cream is so delicious and you look so happy,’ she says, and then pauses. ‘I’m haunted by the survivors who refuse to enjoy life because it would be disrespectful to those who were lost. They feel an obligation to continue suffering, to be the rememberer.’

She tells him about Gerda and her chocolate ice cream and then asks, ‘But why are we here? Why do you and I choose to live in the pain of others?’

‘It’s who we are,’ he says. ‘In di zumerdike teg zol er zitsn shive, un in di vinterdike nekht zikh raysn af di tseyn. On summer days he should mourn, and on winter nights he should torture himself.’

‘But why?’

He shrugs. ‘Because we’re most comfortable when we’re miserable?’

‘I have to remember to tell that to my therapist on Wednesday.’

He bites his cone. ‘I’ve never been to a therapist.’

She looks at him like he’s crazy. ‘You’ve been an eyewitness to a genocide but you’ve never been to a therapist?’

‘Nope.’ He crunches.

She can’t help but laugh. ‘Meshuga.’

‘Now, that’s funny. You’re calling me crazy for not going to therapy.’

They walk back to the car. ‘The only Yiddish I know is from my grandmother. She wasn’t exactly an intellectual,’ she says.

‘Az dos meydl ken nit tantsn zogt, zi az di klezmorim kenen nit shpiln,’ he says. ‘If the girl can’t dance, she says the band can’t play.’

They get into the car and fasten their seat belts. ‘So, Rakel, you who are so good at arranging everything. Where are the kinder this evening?’

She sighs. ‘Ah, Erike, I wanted a weekend like when we were young and used to play hide-and-seek in the pickle barrel, before we had so much responsibility,’ she says. ‘So the children, I loaned them to your brother and my sister. She needed help with her children, he needed help with the harvest.’ She pulls out onto the two-lane road.

‘It’s true,’ he says.‘Our boy is a little no-goodnik who has no idea of what hard work is, and our girl is soft in the head and will have to marry well.’

‘Remind me, how many kinder do we have?’ she asks.

‘Ten,’ he says.

‘So many,’ she says, surprised. ‘And I gave birth to them all?’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘The last three it was less like a birth and more like they just arrived in time for dinner.’

‘It’s true. I remember I was making soup when the eighth came along, and I was bathing the fifth when the ninth announced himself, and the tenth, she arrived at dawn while I was having the most wonderful dream.’

They are quiet; a truck passes, blasting heavy-metal music.

‘You know,’ she says, ‘after the tenth child, I went to the doctor and said, “I’ve lost all sense of who I am, and everything down there feels inside out.” The doctor patted me on the head and said, “When the children grow up and are married, you will know who you are again. And for the rest, I’ll put in a thing.” ’

‘A thing?’

‘A pessary,’ she says, and then pauses and adds in her regular voice, ‘I’ve never used that word before, but I always wanted to.’

‘Can you have sex with a pessary?’ he asks.

‘You haven’t noticed?’ she says, back in character.

‘When the doctor put it in, what did he call it?’

‘He called it a “thing”. He said, “I’ll put in this thing, and you’ll feel better.” And I said, “Will I be able to go?” And he said, “Yes. You will go, and everything will be beautiful again.” ’ She continues, ‘The women talk about him, about whether or not he gets excited when he sees us. He stuck his finger in Sylvie’s ass.’

‘We’re digressing,’ he says.

‘We’re talking dirty,’ she says.

And as they drive into the town, it’s as though they’re coming back from where they’ve been, lost in time.

At the hotel, the crowd from the conference has spilled out of the bar in heated debate. Across the street the local convention center is hosting a gun show, and some of the conferees are considering a protest. There are mixed emotions. Some are desperately urging people not to take to the streets, and others feel that they must act – to do nothing is to allow the show to go on at every level.

‘How do we stop the violence? I’ll tell you how, we organize a group, Nothing Left to Lose. We go in shooting and keep shooting until they realize a gun is no defense,’ one of the men says.

‘He lived this long to be a moron?’ someone asks.

‘He lost his wife recently,’ another says. ‘He’s been very depressed.’

Another man spots the War Correspondent. ‘Can I buy you a drink?’ the man asks, already drunk.

Before the War Correspondent can answer, she is leading him away, down the hall. ‘You want a schnapps?’ she asks.

‘Makhn a shnepsl?’

‘Minibar,’ she says.

When they get to her door, he flicks her do not disturb sign. ‘Are you sure it’s safe? What if something gets disturbed?’

‘Like what?’ There is a pause.

‘If I kissed you, would you hit me?’ he asks.

‘Is that a question or a request? If you kiss me, would you like me to hit you?’

He doesn’t say anything.

She does it, she kisses him. No one hits anyone. She puts her hands up to his face, feels the scruff of his whiskers.

She likes the way he feels. Lisa is small, her skin smooth – she’s a sliver of a person, like a sliced almond.

And then the door is open. He takes a Scotch from the minibar, swallows it like medicine.

‘Have you ever slept with a man?’

‘Is that an offer or a question?’

He doesn’t answer.

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘Have you ever slept with a lesbian? Maybe that’s the real question?’

‘Who initiates? Like, is it always the same lesbian each time, or do you take turns?’

She untucks his shirt. His skin is warm, the fur on his belly is long. His body is both soft and hard, fit but not muscle-bound.

‘This is not what lesbians do,’ he says.

‘You have no idea what lesbians do,’ she says.

‘Tell me,’ he says.

‘We give each other blow jobs.’

‘What do you blow?’

‘Giant dildos and chocolate cocks,’ she says, pointing to the still-unopened box.

‘You’re exciting me,’ he says.

‘You’ve always excited me,’ she says. ‘It’s been a long time . . .’

‘How long?’

‘Sometime in college,’ she says.

‘Is it scary?’

She laughs. ‘I thought you were going to say liberating.’ She unzips his pants and takes him in hand.

‘I really like your . . .’

‘Member?’ he suggests.

‘Friend?’ she says. ‘Seriously, it’s beautiful.’

‘Thanks. But are you just going to examine it, or . . . ?’

‘I can’t help it. I love a penis.’

He laughs. ‘You are so not what I expected.’

She is teasing him with her mouth, her hands, her body.

‘You’re killing me,’ he says.

‘We are at a genocide conference.’

‘It’s not a joke,’ he says.

‘Behave,’ she says. ‘Would it be easier if I tied you up?’

He snorts.

‘How about you just lie down and be quiet,’ she says.

His body is the other, in opposition, distinction, in relation. The weight of him, the musky scent, is delicious. His mouth tastes of Scotch and ice cream.

‘I bet you get laid a lot,’ she says. ‘Do I need to worry?’

‘No,’ he says.

‘Is that true, or do you just not want to be distracted?’

‘Do you want me to use a condom?’

‘No,’ she says. ‘I want to feel it.’

Their sex is meaty, almost combative, every man for him/herself. When he turns her over and takes her from the back, his desire is apparent. She is humbled and overwhelmed by the power of the male body. It wants what it wants and will take it until satisfied. A penis connected to a man is entirely different from the strap-on or the rabbit wand Lisa brought with her from a previous relationship. All of them are like artificial limbs, prosthetic antifucks, but this, she thinks, this is amazingly good.

‘Is this making love?’ she asks, not realizing she’s speaking aloud.

‘It’s fucking,’ he says.

‘Is it okay?’ he asks, suddenly self-conscious.

‘Yes,’ she says, not thinking about him but about how much she’s enjoying herself.

And then, as they’re getting close to the good part, she can’t help herself and anxiety pulls her out of the moment.

‘Is it true that once a guy starts, he won’t stop till he comes?’

‘I don’t know,’ he says, annoyed.

His annoyance exacerbates her anxiety. ‘I think it’s true,’ she says.

He slows down for a moment. ‘What about lesbians?’ he says. ‘Do lesbians stop?’

‘Sometimes,’ she says. ‘Sometimes right in the middle they just give up and stop. It fails to escalate, or someone says something and it de-escalates.’

‘Do you usually talk the whole time?’

‘Yes,’ she says.

‘Maybe that’s part of the problem.’

They finish coated in each other.

The Shabbos lay is a very good thing, a blessing.

There is quiet and then sounds from across the street. ‘You want to shoot someone, shoot me,’ Gerda Hoff says, standing in the street. ‘You like guns so much,’ Gerda says. ‘You have no idea. Those don’t protect anyone. You want to feel like a big boy, so shoot me.’

‘She’s asking for it,’ a young guy from the gun show says. ‘Shoot her.’

‘That’s not amusing, Karl,’ the other guy says.

‘Karl. What a name, like Karl Brandt,’ Gerda says.

‘Who’s he?’

‘Exactly,’ she says. ‘You have no idea who you are or where you come from. Karl Brandt was the Nazi who came up with the idea of gassing the Jews.’

The guy from the gun show is impressed, like he thinks this Karl is cool.

‘He was hanged for his crimes on June second, 1948. He should have been hanged six million times.’

The Novelist is at the window – the War Correspondent behind her.

‘Is Gerda okay?’ she asks.

‘Yes,’ he says.

‘This isn’t going to turn into some fucked-up thing where a little old lady dies on Main Street?’

‘No,’ he says.

‘She’s going to come inside and eat chocolate ice cream?’ She starts to cry. ‘We cheated,’ she says.

‘Have you ever done it before?’

‘No,’ she says. ‘You?’

‘Yes,’ he says.

‘You asshole,’ she says, punching him.

He laughs. ‘I’m an asshole because I’ve done it before?’

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘If you cheat, it should be something special, not something you just do all the time.’

‘I didn’t say I did it all the time. Noch di chupeh iz shepet di charoteh. After the wedding it’s too late to have regrets.’ There’s a pause. ‘Now you’re mad at me.’

She doesn’t laugh. ‘I’m not mad, I’m disappointed. I should get some work done,’ she says.

She can’t imagine actually sleeping with him there.

‘Is that what you do?’ he asks.

‘I’m a night owl,’ she says. ‘And there is no “Is this what I do?” because I don’t do this!’

She looks out the window again. A small crowd has formed. The guys from the gun show have no idea what’s going on, except that they’re in a standoff with a bunch of senior citizens. A police car rolls up, the crowd dissipates, Gerda and her gang walk back across the street.

He gathers his things. ‘See you in the morning.’

She turns – he’s wearing the hotel robe. ‘You’re going out like that?’ She sounds exactly like her mother.

‘Yes,’ he says.

‘Someone might see you.’

‘I’ll tell them my shower was broken and I used yours. PS, now I’ve seen you naked.’

He opens the door and stands for a moment half in, half out of the room. ‘Do you want to go apple picking tomorrow afternoon?’

‘What?’

He makes the gesture of picking apples from trees. ‘Now’s the moment, this is the season, the guy who gave me a ride from the airport said there’s a nice orchard near here.’

She almost starts to cry again, ‘Yeah, okay, after our panels we’ll go apple picking and we’ll play Jew again.’

‘Play Jew? Is it like a game show? “I’ll take Torah for two hundred”?’ he asks.

‘I have no idea,’ she says, closing the door.

Do you want to go apple picking? It’s the nicest thing anyone’s ever said to her.

She turns on the television and calls home, not because she wants to but because that’s what she does.

‘Why so late?’ Lisa asks.

‘I was kibitzing with someone.’

‘Your voice sounds funny. Are you getting sick?’

Her voice sounds funny because she just had a dick in her mouth. ‘I’m just tired,’ she says. ‘And you?’

‘All fine,’ Lisa says. ‘I’m here with the cat and beating your mother at Words with Friends online.’ She’s super proud because she just got “jest” for thirteen, but she doesn’t know I’m sitting on X and Y, and I’ve got big plans.’

‘Nice,’ she says, thinking of apple picking.

She sleeps badly. At some point there’s something cold and slithery crawling up her leg, but then she realizes it’s the opposite, it’s ‘stuff’ running down her leg. She dabs at it with her fingers, tastes it.

At breakfast a handmade Post-it hangs over the steam trays of scrambled eggs and gray sausages that look like turds: fyi – not kosher.

There are single-serving boxes of cereal and a plate of what looks like homemade babka someone has cut into pieces.

She takes a piece of babka with her coffee. Her eyes sweep the room, looking for him and glad not to see him – as long as he’s not somewhere else, avoiding her. On a wipe board someone has written, ‘Otto Hauser’s Accepting Responsibility has been rescheduled for 9.30 this morning in Ballroom B.’

Coffee and babka in hand, she locates Hauser, the self-described obsessive-compulsive whose guilt about civilian passivity during the war led him to relentlessly collect and catalog the personal effects of those who disappeared. He is ‘the’ Holocaust-ephemera specialist, the man who doesn’t want to be known.

‘Mr Hauser?’

He looks up. His eyes are a beautiful blue clouded by the watery milk-white of old age.

‘I’m sorry to bother you . . .’

He pats the chair next to him. ‘Sit.’

‘I’m sure you get asked all the time, but would you tell me a bit about how you came to be the Accidental Archivist?’

He pours hot water from a pot into a teacup. ‘My mother was very tidy,’ he says as he dips his tea bag up and down. His English is that of a German who learned to speak by listening to radio shows. ‘She wasn’t an intellectual, but she knew right from wrong. She was very German, very organized. So when people were taken, she would slip into their houses and recover things, before looters, mostly soldiers, came. Slowly it became known in the Jewish community, and people would bring her things to hold for them, knowing soon would come the knock on the door. My mother was very clever, good at hiding things – she put them in boxes marked as Christmas ornaments, sewing supplies, or Papa’s military uniform, and they never looked. She took them to her father’s farm and buried them in the field as they harvested crops. She didn’t keep a notebook, but she made a code. She kept track of everything and waited for the people to come back. Near the end of the war, quite suddenly she died. I was a young man. I carried on my mother’s work so she would be proud. The war undid us all – we never recovered.’

‘And did the families come back?’

He shakes his head. He begins to cry, and she finds herself surprised by his tears, as though after so many years he wouldn’t cry anymore. ‘No,’ he says. ‘And still, in the fields of my grandfather’s farm, we find things – a silver teapot, a pointer for the Torah, candlesticks. For years I waited. Now I’m an old man. I never married, I have no family. I’m so old that I am actually shrinking.’ He gestures at his pants, which are held up by suspenders. ‘I kept everything, but I realized these things should be in circulation, not in a box somewhere, unable to breathe. I started to give them to schools, museums, synagogues, to people who needed something to hold – an object of remembrance.’

‘And why did you want them to take you out of the film?’

‘Because I am not a hero,’ he says. ‘I am just a man.’ Otto stands, and he is almost elfin. ‘What I have come to comprehend is that it is less about the object and more about the head.’ He taps his head, the aha moment, and takes off toddling toward Ballroom B.

‘So nice,’ one of the women says, catching her more than an hour later, as she’s leaving the room. ‘You don’t just come to talk, you also listen.’

‘You’re late,’ her mother says. ‘You usually call at eight thirty. When you don’t call, I don’t get up. I don’t brush my teeth. You’re what starts my day. So what happened, your alarm didn’t go off ?’

‘I love you,’ she says. ‘You are what starts my day, too.’ She is thinking about what Otto said about the head and the transformation of the heart and the way one moves through life.

‘So,’ her mother says. ‘If you have me to be the woman in your life, what do you need Lisa for? She can’t spell. What you need with your dyslexia is someone who can spell.’

She laughs.

‘I’m not kidding.’

She finds the War Correspondent after his panel has ended and waits while he signs copies of his book. ‘Yes, we did wear vests that said press so people knew who we were,’ he tells a man, ‘but we stopped when we became higher-value targets.’ What is he like as bullets are whizzing past or when men with machetes appear in the middle of the night? What is the balance between excitement and terror?

When he’s finished, they escape into the day. She hands him the keys. ‘You drive.’

‘Rakel, I live in New City,’ he confesses. ‘I am a perpetual passenger. I have no license.’

Even Lisa drives.

The orchard is ripe with families and children and bumblebees buzzing. They debate between buying a half-bushel basket and a bushel and agree that a half is only a half, and so they buy a bushel basket and head into the fields.

‘Erike, how was it today in town?’ she asks as they walk down the rows of the orchard, past signs that say ripe this way.

‘I got new shoes for the horse, and I saw my cousin Heschl. He has troubles that one cannot speak about.’

‘His daughter?’

‘No, his son.’

She shakes her head, tsk, tsk, and thinks of her therapist, clucking.

Picking apples off the trees, they search for ones that are ripe, that come to them with only a tug. They polish the apples to a shine on their shirts and bite from the same apple at the same time – the skin crisp, the flavor sweet, the texture meaty and young. A few bites and then it is discarded as they hunt for the next one. He lifts her to get the perfect one from the top of a tree and then asks her to wait while he runs to the farm stand and buys a jar of honey.

He pours the honey on the apples they eat. Honey runs down his hands; his fingers are in her mouth – it’s sticky.

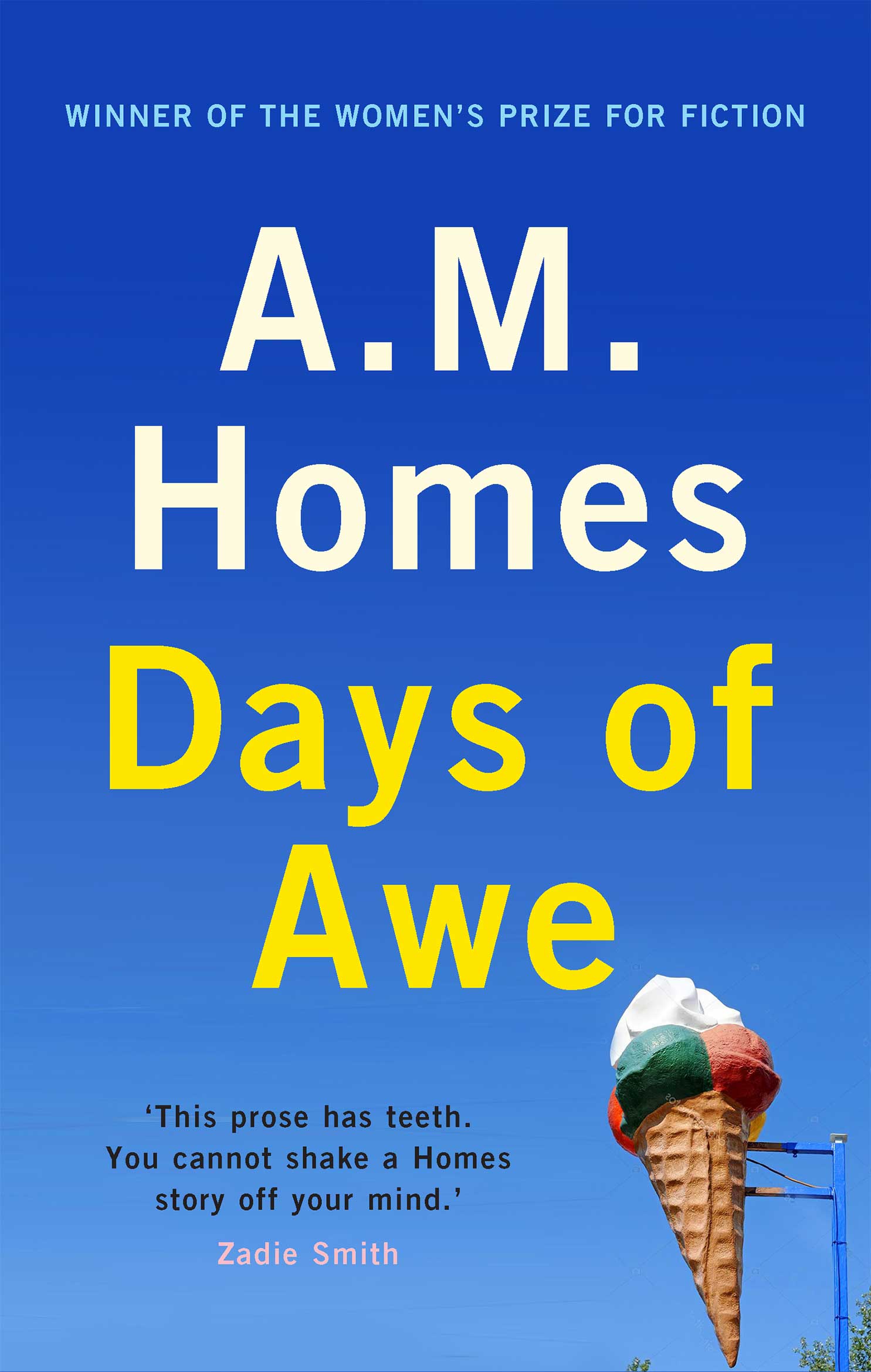

They celebrate early New Year. Rosh Hashanah is next week, the beginning of the Days of Awe.

‘I want to have you right here in the orchard,’ he says, lifting her skirt, unzipping his pants, his shirt hiding the details.

Does anyone see them pressed into a tree, his comic humping causing ripe fruit to fall on their heads?

She pushes him off, laughing, ‘Erike, put that away. You’re acting like you’ve got pickles in your keppe. We’re in public.’

Reluctantly, he zips up. ‘I’ll tell you something about genocides that people don’t talk about.’

She waits.

‘They fucked a lot. They fucked all the time, because they needed the relief, they needed not to think for a brief moment, needed to remind themselves that they were human, and because they knew they were going to die.’

‘Even when the world is not at war, we all still die,’ she says, picking another apple, dropping it in the nearly empty basket. There is the sound of apple hitting apple – bruising.

‘When we used to hang around together, none of the guys ever asked me out.’

Another apple dropped into the basket.

‘They just wanted to get laid. They didn’t want to contend with someone.’

‘And that’s why I’m gay,’ she says, dropping in a sour green apple.

‘Because you couldn’t get laid?’

‘It’s not like I couldn’t get laid. I just couldn’t get laid by a peer, because the girl has to be less than equal,’ she says, climbing a short ladder against the trunk of a tree. ‘She has to tell you that you’re wonderful and powerful and all those things, but what about her? Isn’t she also wonderful and powerful, or is she just the girl you fuck? And I’m not so much talking about you – you were married to your wife, whatever her name was . . .’

‘Marcy.’

‘You were married to Marcy, and I was busy fucking Saul Stravinsky.’

‘You were fucking Saul Stravinksy? Did any of us know? He was my hero.’

‘He was everyone’s hero,’ she says. ‘And he was an ass. The thing he liked about me was that I didn’t care – I treated him worse than he treated me, and he seemed to like that. And he taught me a thing or two.’

‘About sex?’

‘About editing.’

‘Marcy and I went to hear him read at the 92nd Street Y with Philip Roth. It was an incredible pissing contest. He and Roth clearly hated each other, which makes sense – they were practically the same person.’

‘I am aware,’ she says. ‘I was there, giving him an encouraging blow job in the bathroom of the green room.’

He shakes his head.

‘You know about the ball hairs?’

Again he shakes his head no.

‘Saul’s second wife wrote a memoir about their marriage, The Door Was Always Open. She went on about how much he loved his balls because they were so big – “Bigger than Brando’s,” he used to say.’

‘Stop!’ Erike cries abruptly. ‘I can’t hear any more. Some things should remain a mystery.’

‘I have one of his ball hairs,’ she continues. ‘It’s what the women who slept with him did. We’d take a hair, put it in a clear glass ball, like how people do with dandelion pods, and wear them on a chain around our neck. Hairs from the nut. Twice a year we have tea, usually eight or ten of us.’

He stares at her in disbelief.

‘Google it,’ she says. ‘One of them rather famously wrote about it.’

‘We’re sitting in an apple orchard on a beautiful day, we escaped a genocide conference, and you’re telling me about Saul Stravinsky’s balls?’ He is genuinely dismayed. ‘Seriously – it was all incredible. I was humping you, eating Granny Smiths, and celebrating the coming New Year. I was about to put an Empire in your mouth, truss you up against the vines, and you start talking about Saul Stravinsky.’

‘Do you think you might be overreacting?’

‘No,’ he says. ‘No.’ He sits on the ground, like a child sulking.

‘Really?’

‘I don’t know,’ he says.

‘Can I change the subject? This morning I heard a guy ask you about wearing a press vest, and you said that press are high-value targets now.’

He nods.

‘How close are you to things when they really get going?’

‘I’m standing right there. I have a flak jacket, a helmet, a recorder, a pad and pen, and a camera, even though I take terrible pictures.’

‘And if you see something bad happening or about to happen, do you do something, like say, “Hey, I think there are bad guys coming” or “Wait, there’s a kid in there”?’

‘I’m a journalist, not a soldier.’

‘But what does that really mean?’

‘As I said to the guy who called me a pussy, I’m there to observe and report, not to interfere. I am a witness.’

‘You stand by and watch while people are killed?’

He says nothing.

‘Is there something more you could be doing?’ she asks, and immediately realizes she sounds just like her mother; she’s blaming him for not doing enough.

‘Even if I got in the middle of it, it wouldn’t change things.’

‘You sound defensive.’

‘I am,’ he says. ‘And by the way, I do get involved. I try to bring humanity to the situation. My pockets are always full of treats for the children, Starbursts and Twizzlers, because everyone likes candy and they don’t melt in the heat.’

‘You’re involved because you give away candy? Is that what you just said?’

He stands up and faces her, like a gorilla making himself big to intimidate. ‘Yes, that’s what I do. I go through war zones with Smarties in my pocket. You have no idea what you’re talking about,’ he says. ‘Your stuff isn’t even real, you just make it up.’

‘Are you picking a fight?’

‘You’re the one picking it.’

‘Clever, trying to make the pickee the picker. Just because it’s fiction, that doesn’t mean it’s not true. What you’re saying is that your observations, standing there and doing nothing while people are being killed, are more important than my spending seven years developing a layered, multigenerational narrative that spans decades, giving voice to those who aren’t here to represent themselves.’

‘Truth is stronger than fiction.’

She almost says, ‘You’re entitled to your opinion,’ but catches herself. ‘Truth isn’t synonymous with history. The point of fiction is to create a world others can inhabit, to illuminate and tell a story that stirs empathy and compassion. And, asshole,’ she adds, ‘fiction helps us to comprehend the incomprehensible.’

‘You have no idea what you’re talking about,’ he says, his voice both full and tight with emotion. ‘I have seen a mine explode under a woman’s feet as she’s carrying her baby, watched as the woman is sheared off below the waist and the baby becomes a projectile flying through the air, a vision that in another context might be magical, but here it is magic turned to murder as the baby lands on a car, still, eyes fixed, heart stopped, a life smashed. The dying mother is asking about her baby while others are gathering the parts of her body that have been separated. A man comes with her leg, carrying it like an offering, like perhaps it might be reattached. Dark blood

is staining the ground. That night the mother and baby were buried together. It’s too much for the brain to process to see bodies no longer whole, parts of a person. It’s a shattering of the self. I helped dig the grave,’ he says. ‘I have helped dig many graves. How’s that for the incomprehensible? Does that help? Is that doing something?’

‘You win,’ she says, noticing that it’s the same thing she does with Lisa. She wants the fight, and then she can’t deal with it. ‘You saw it happen. You wrote it. You carry it with you – full score. It’s both beautiful and devastating.’

‘It’s not a competition,’ he says.

‘It is, and that’s what’s pathetic. A minute ago you told me that what I did somehow wasn’t weighty enough, or real. Is the desire to dominate, to win, fundamental to human nature? Is man’s cruelty to man a fact of life? Are we such animals? There is a rank and an order that over time inevitably leads to extinction. The big question is, what are the obligations of consciousness? Can we train ourselves to do things differently? That’s why we’re here, asshole.’

‘You keep calling me “asshole” like you’ve decided that’s my new name.’

‘We’re not real,’ she says. ‘The true witnesses are those who died, those who were stripped naked and gassed, those who were hacked to death by others they grew up with, young men covered in sarcoma sores, wasting away, whose parents wouldn’t even come and say goodbye. We are the witnesses’ witness. I come to these conferences to acknowledge them; they need each other, but they also need the rest of the world to say, “I see you.” ’

Silence.

‘There is something wrong with me,’ he says. ‘I keep having to go back, again and again.’

‘I’m the same,’ she says.

‘I go around the world, to different places, to see things that no one else should see. I need it to have an effect on me, to get through to me and wake me up.’

‘And then what? What would you be if you were awake? Would you realize that you’re an impostor, that you’re just a man in pain, not a hero, just human? And then what would you do?’

‘I have no idea,’ he says. ‘It’s like I need to be punished. Again and again I go back.’

‘Well, let’s find out. You’re walking home from here,’ she says. She has no idea where that idea came from; it just came out of her mouth.

‘Have you been taken by a dybbuk?’ he asks. ‘It’s miles.’

She carries the almost-half-empty bushel of apples and the jar of honey to the car and drives off. She has no idea what she’s done or why, has no idea about anything that’s happened in the last twenty-four hours. A dybbuk indeed – would that hold up in court? She drives toward town and then five minutes later abruptly turns around and goes back, expecting to find him walking along the side of the road. He’s nowhere. Feeling horrible for having left him, she drives up and down looking – nothing. She leaves telling herself he’s a big boy, he’s been in war zones, he can get himself home from an apple orchard.

Whatever it was, whatever it might have been – done. Over. Finis.

As she’s driving, she’s thinking about what they were doing, the way they were playing with each other, the freedom of their conversation as imaginary others. Her mind goes back to Otto that morning at breakfast.

‘The games children play – war, cops and robbers – always good guys and bad. There is something there, something about human behavior?’ He paused. ‘I had a frightening thing happen to me last time I was in America. I was speaking at a university in Virginia, and I went to walk around the town. There was an antiques store. I was wondering what is an American antique, what objects do they keep. So I went in. There were old ceramic bowls, heavy wooden benches, a thick black kettle one would put over an open fire, American

flags, a sign from a feed store. And near the back of the store, I see something hanging; at first I think it is a decoration, a ghost for Halloween, white hand-sewn muslin, and then I realize it is something else. The head comes to a point, like a cone . . . It is a white sheet with a pointed hood.’

At the hotel she washes the apples in her bathroom sink. She writes a note, pausing to look up the number of the Jewish New Year: ‘Fresh-Picked Happy New Year 5778.’

She brings the apples and the jar of honey down to the bar and leaves them on the table near the juices from Be My Squeeze. Philanthropy is the opposite of misanthropy.

‘You see what’s happened, don’t you?’ Otto said to her that morning over babka. ‘It spreads from generation to

generation. It becomes the child’s task to mourn because the parents can’t. They survived, but they are frozen, holding their breath for forty years, not really alive. It is the job of the children, representing the dead.’

Back in her room, she calls her mother again.

‘She cheated,’ her mother says.

Her heart hears before her head – tachycardia. ‘Pardon?’

‘Lisa cheated.’

‘Mom, what are you talking about?’

Her mother starts again, louder, slower. ‘Your girlfriend, L-I-S-A . . . and I, we were playing Words last night on our phones, and I think she cheated. “Xyster”.’

‘I have to call you back,’ she says, hanging up.

A break. A moment. She can’t say what she did, she doesn’t know; did she lose consciousness? Did she throw something, smash her own head against the bathroom wall? Vomit? She has no idea except that time passed.

She calls Lisa.

‘You mother is mad at me because I beat her at Words,’ Lisa says.

There is silence.

‘Hello?’ Lisa says.

‘My mother says you cheated,’ she says, too calmly.

‘Are you out of your mind? Your mother kept telling me that my words weren’t real. She said that “scry” was an internet abbreviation and didn’t count . . . And that tone. You’re speaking to me in that tone, imperious, as though you’re sure you know something.’

‘Fine, then tell me I’m wrong,’ she says.

‘I don’t need to tell you you’re wrong, because you know you’re wrong. And you know what, Little Miss Permanent Griever, that’s what I call you in my knitting group, the Permanent Griever. You’re the girl who goes to Holocaust conventions all over the world and grieves for others because she can’t feel anything in her own life.’

‘Are you sure you want to go there?’ she says, stunned. It’s not like Lisa to be mean or go off.

‘You know what? I don’t have to go anywhere,’ Lisa says, ‘because you’re the one who goes. You run away, you never deal with anything, you never even play Words with your own mother. Damn you,’

she says.

‘This is the fight,’ she says.

‘Yes. Damn it,’ Lisa says. ‘This is the fight I thought we’d have before you left, but I guess we’re having it now. I guess we’re having it while you’re away because it would be too hard to have it when you got back, because then we’d have to deal with things.’

‘Exactly,’ she says.

‘Exactly what?’ Lisa says.

‘Exactly what you said. You’re right,’ she says. ‘You win. Touché.’

‘I’m not trying to win, I’m actually trying to talk to you – but apparently that’s not possible.’

‘Right again,’ she says.

‘Stop it,’ Lisa says. ‘Just stop it.’

‘I’m not doing anything except saying that you’re right. All the things you just said are entirely right. Now what?’ Silence. ‘What do you want to do?’ she asks.

‘I don’t know,’ Lisa says. ‘Are we supposed to do something? I just wanted to talk. Why don’t we just put a pin in it?’

‘Aroyslozn di kats fun zak,’ she says.

‘I have no idea what that means,’ Lisa says.

‘It’s Yiddish for letting the cat out of the bag.’

‘I’m sorry we fought,’ Lisa says.

‘So the note says,’ she points out. ‘I have to go.’

‘That’s it? A thunderclap argument and you have to go?’

‘I have a panel.’

‘You do not. I have your schedule right here. Your last panel was this morning.’

‘It’s a pop-up panel on Gerda Hoff, the survivor who wrote the cancer memoir, Living to Live,’ she says, surprising herself with her impromptu fib. ‘Gerda is a remarkable woman, feisty. And she loves chocolate.’

‘Bring her a thing,’ Lisa says.

‘Not funny.’ A pause. ‘And I’m sorry, too,’ she says. ‘I really am. Everything you said is true. I suck at talking about things. And yes, for some strange reason I am deeply attracted to the pain of others.

I can’t say more – except to agree with you.’

‘Fine,’ Lisa says. ‘Do me a favor?’

‘What?’

‘Be nicer to your mother.’

She sits, she tries to meditate, her mind is spinning in all directions. She thinks of Otto; how was it that without knowing him she had been so deeply drawn to him, had been determined to find him, to hear his story? And without knowing her, he knew her so well. She thinks of Lisa and sees that she herself is the one who is a child. She expects Lisa to demand something of her that she needs to demand of herself. She can’t wait to tell the therapist, who she imagines will be impressed or worse. The therapist might say something like, You seem pleased with this idea, but what can you tell me about what it means to you?

She hears Otto’s voice from this morning: ‘I recently read a book that had been translated about a family where the uncles had been sent to the camps. The children, who never knew the uncles, grew up playing prison camp the way others played house or school.

‘ “Dance for me,” the guard says, and the little boy dances. “Tell me stories,” the guard says, and the little girl tells stories. “Make me some lunch,” the guard says, and the children sneak upstairs and make sandwiches and bring them back down. The guard does not share. “We are hungry, too,” the children say. “No food for you.” “But it is lunchtime for us, too.” “Eat worms,” the guard says. “Now I’m tired,” the guard says. “Take care of yourselves for a little bit. And while I am sleeping, walk my dog and do my homework.” ’

‘The Re-enactments,’ she said to Otto. ‘That’s a scene from my book.’

‘It was beautiful,’ Otto said. ‘But you see from the way the children handled the box that had been so carefully carried from place to place for many years and how frightened they looked when it broke open and spilled across the floor that it had become a myth. And then, when the box was broken, what did they do with the treasures that had belonged to the uncles? They put them in their game. They didn’t make them precious, they brought them to life.’

She wrote it. She lived it, too, in the basement of her cousin’s house.

‘What you see,’ Otto said, ‘is that history can’t be contained, cannot be kept in a box. As much as we might want to keep the past where it was, it is always present. We carry it with us, not just in our grandmother’s silver but in our bodies, the cells of our hearts. And that is why I am here. I am the person with the containers who wants to tell everyone – dump it out, pour it, let it spill. This is it, bisl lam, this is all you get. And, I might add, even for those who believe there is another world, a place we go when we are no longer here – they’re not kidding when they say you can’t take it with you.’

She sits, she tries to meditate, but instead she weeps inconsolably for a very long time. She weeps until she runs out of tears, and then she sits silent and dry.

He knocks on her door, face flushed pink, dripping with sweat, shirt stained, smelling like a buffalo.

‘What are you so happy about?’ she asks, blotting her eyes. ‘You look ecstatic.’

‘At first I was furious. You left me there by the side of the road. It was like you dropped me on my head. But then the walk was amazing. I crossed a Revolutionary War battlefield with the rolling hills in the background, and for the first time I had the physical sense of what it was our ancestors fought for. When I got tired, I hitchhiked. I got a ride in the back of a pickup truck with a pair of giant, very well-trained German shepherds.

She touches something brown on his shirt. ‘What is this on you, shit?’

‘I think it’s chocolate. I stopped for ice cream.’

‘The walk was supposed to be your punishment, and you got ice cream?’

He nods, guilty, like a small child. ‘I had a vanilla-and-chocolate twist with a dip into the chocolate that hardens. They called it a Brown Cow. It was fantastic. I hadn’t had one since I was a kid on Cape Cod.’

‘You went to the same place we went last night – it was in the opposite direction of where I left you?’ she asks, incredulous.

‘No,’ he says. ‘A different place, The Farmer’s Daughter.’

She’s irritated, almost jealous; he got ice cream and rode in a pickup truck. ‘Everything for you is a sublime experience.’

‘What have you been doing?’

‘Me?’ She’s tempted to tell him there was a pop-up panel with Gerda Hoff. ‘I was fighting,’ she says. ‘With my mother and then with Lisa.’

‘Ah,’ he says, nodding. ‘Do you know what’s happening downstairs right now?’

She shakes her head no.

‘Stand-up comedy,’ he says.

‘Holocaust humor?’

‘Actually, a black guy from South Africa, followed by an open cabaret: Songs and Stories from Distant Lands. Do you mind?’ he asks as he opens the minibar. ‘I don’t feel very good. Everything hurts.’

‘You walked too far. Too much sun. Tylenol or Motrin?’ she asks. ‘Do you have any allergies?’

‘And now you’re a doctor?’

‘At least you didn’t say nurse.’

He washes down Motrin with Scotch and pulls her toward him.

‘You stink,’ she says, pushing him into the bathroom, turning on the shower. He can’t tell if she’s really mad, and neither can she.

‘Do you know that I’m named after Harry Houdini? And I think that’s why I slip through so many situations,’ he says from inside the shower.

‘What?’

‘Harry Houdini’s real name was Erik Weisz. He was the son of a rabbi.’

She’s giving herself a cold, hard look in the bathroom mirror. She is thinking about what they both do; they are professional witnesses, reminding others to pay attention, keeping the experience alive, hoping that the memory will prevent it from happening again. She is wondering what they’re both so afraid of that it has stopped them from living their own lives. She is not paying attention to him. He splashes her with water. Her shirt quickly becomes see-through.

‘You want the world to see what is private to me?’

‘Yes,’ he says, ‘I want to see you. I want to look at you the way you looked at me yesterday.’

He is pulling at her clothes.

‘Stop, you’re ripping it.’

‘I don’t care. Tomorrow I’ll go to Orchard Street and buy you new underwear.’

‘I hate you,’ she says. ‘You ever suck cock?’

‘No.’

She brings the box from Lisa into the bathroom and rips it open. Three chocolate cocks fall out: pink, milk, and dark.

‘Are you going to fuck me with those? Is that what lesbians do?’

‘You’re going to suck it,’ she says.

They both almost laugh but catch themselves.

‘Do you have a safe word?’ she asks.

‘Like my password?’

‘No, a safe word for sex play, like a way of crying uncle if you want to stop.’

‘Roth1933,’ he says. ‘It’s my password, too. Now you can take me for all I’m worth. What’s yours?’

‘Ovum,’ she says, slipping the dark chocolate dick into his

mouth.

His hands find her female form in ways that are entirely different from Lisa’s. Lisa likes her arms, the cut of the biceps, her shoulders. His hands are on the curve of her hips, grabbing her ass, lifting her onto him.

They are doing things with each other and to each other that have them on the verge of hysteria – they are laughing, crying. They are outside themselves, and they are themselves, and then they are asleep.

In the morning there is a circle on his chest like a bullseye.

‘You have Lyme disease.’

‘It doesn’t happen that fast,’ he says.

‘Sometimes it does.’

They kiss. The kiss is deep and filled with a thousand years of longing, a thousand years of grief. They part for breath, laughing – they both know. She bites him hard on the shoulder, her teeth catching the muscle, leaving a mark.

The conference is over. There is no goodbye, because if they said goodbye, it would mean that something had ended.

‘What I’ve learned after being the keeper of the grief,’ Otto said, ‘is that letting go doesn’t mean you forget, but you find freedom, the room to continue on. There is the fear of forgetting, but it doesn’t happen. One learns to live with the past and allow oneself and others a future. One never forgets.’

She drives to the airport, drops off her car, and gets on the plane. She wishes the plane were a time machine, a portal to another world. She wishes it would take her somewhere else.

She is home before Lisa gets back from work.

‘How was the conference?’ Lisa asks.

‘Good,’ she says as they are making dinner. ‘I met Otto Hauser.’

‘Your hero,’ Lisa says.

‘My hero,’ she says.

Are they going to talk? Are they going to break up?

Lisa says nothing more about the fight, and neither does she. She brought two chocolate cocks back with her. After dinner she offers them to Lisa. ‘Which do you want?’

‘I just want you,’ Lisa says, patting the sofa next to her. She sits next to Lisa. The cat jumps up and gives her a big sniff and makes a couple of circles before jumping across her and curling up on Lisa’s lap.

Time passes. She writes the War Correspondent into a short story. He’s disguised as a Buddhist poet and she as a brain surgeon. They meet when he bumps his head. They have nothing in common except a koan.

She forgets about the chocolate cocks until she discovers them one day at the back of the fridge. She melts them down and bakes them, pink and milk chocolate, into a chocolate swirl bread – a babka of sorts.

She thinks of Otto. ‘You know who comes to my talks these days? People who are still fighting. In Israel they call ahead into Gaza and say, “You have five minutes. We are coming to bomb your neighborhood. Get out.” They call it “the knock on the roof”. It seems polite but strange – you tell people ahead of time that you’re coming to kill them? It reveals to me we have made a habit of treating each other like this. Old habits are hard to break.’

And then he took her head between his hands and kissed her on the head. ‘Shepsela,’ he said. ‘Du bist sheyn.’

Photograph © Harold Edgerton / MIT, Bullet through apple, 1964, Courtesy of Palm Press, Inc.