The note had been typed out, folded over two times. It had been pinned to the child’s chest. It could not be missed. And like all the other notes that went home with the child, her mother removed the pin and threw it away. If the contents were important, a phone call would be made to the home. And there had been no such call.

The family lived in a small apartment with two rooms. On the wall of the main room was a tiny painting with a brown bend at the centre. That brown bend was supposed to be a bridge, and the blots of red and orange brushed in around it were supposed to be trees. It was her father who had painted this. Now he doesn’t paint anything like that, not since he started at the print shop, smelling like the paint thinner he was around all day. That smell, like lady nail polish, never left him, not even after he’d had a shower. When he came home, first thing he always did was kick off his shoes. Then, he’d hand over a roll of newspaper to the child, who unfolded sheets on the floor, forming a square, and around that square they sat down to have dinner.

For dinner, it was cabbage and chitterlings. The butcher either threw the stuff away or had it out on display for cheap so her mother bought bags and bags from him and put them in the fridge. There were so many ways to cook these: in a broth with ginger and noodles, grilled over charcoal fire, stewed with the bits that came from the discards, or the way the child liked them best – baked in the oven with lemongrass and salt. When the child took these items to school, other children would tease her about the smell. What that smell was that was so bad, the child had no idea. ‘You all don’t know what a delicacy is. You wouldn’t know a good thing even if it came five hundred pounds and sat on your face! Fools, you are.’

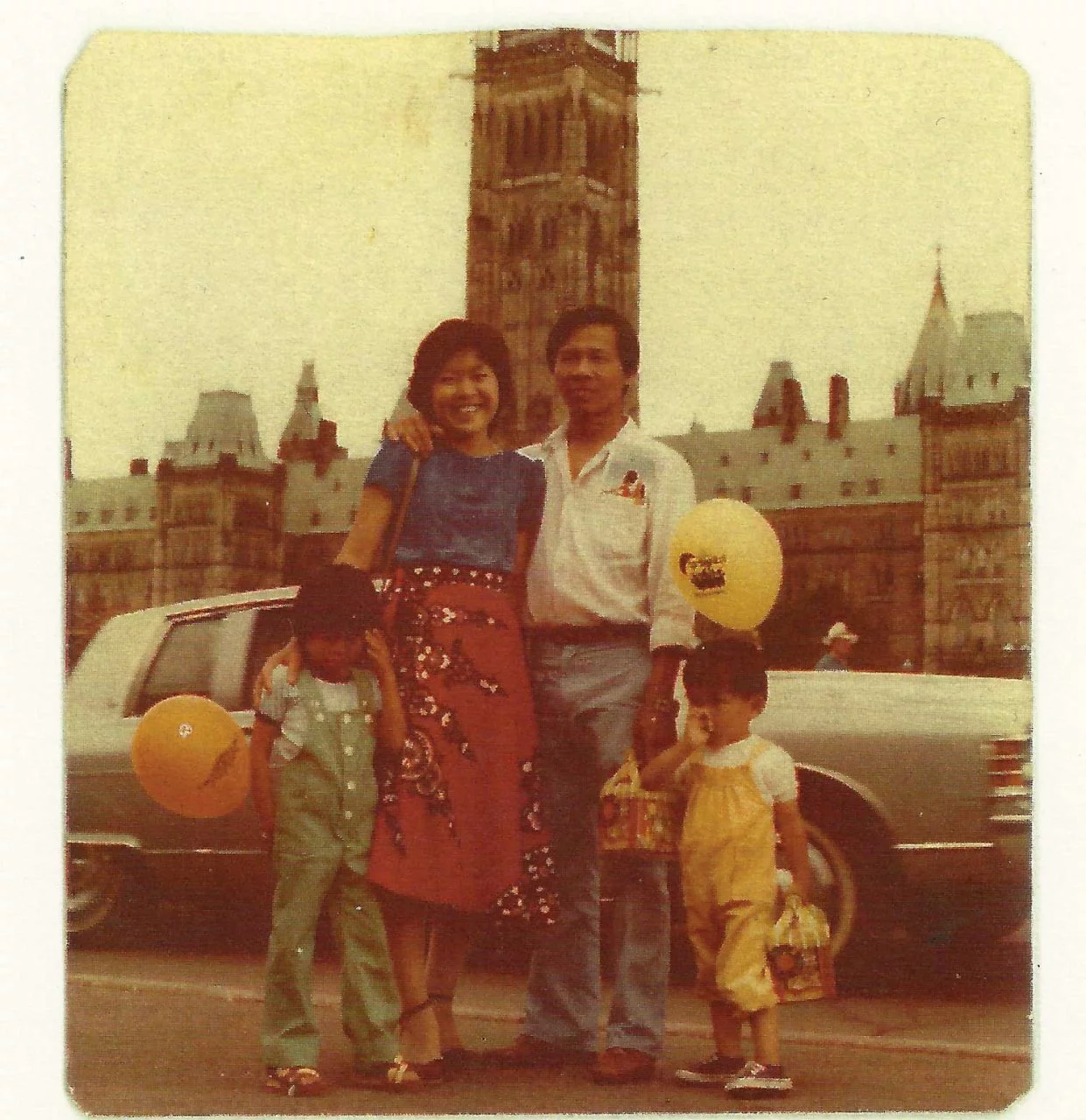

Souvankham Thammavongsa with her parents, Sisouvanh and Phouk,

and her brother, John, after their Canadian citizenship ceremony, Ottawa, 1983

When they all sat down for dinner, the child thought of the note, about bringing it to her father. There had been so many, but maybe this one was important. Her father thought about his pay and his friends and how they were all making their living now. He himself wasn’t educated, but the ones who were found themselves picking worms or being managed by pimple-faced teenagers. When the child got up and brought the note over to him, her father waved it away, said, ‘Later.’ He said this in Lao. And then he remembered. He said, in Lao, ‘Don’t speak Lao and don’t tell anyone you are Lao. It’s no good to tell people where you’re from.’ The child looked to the centre of her father’s chest, where, on this T-shirt, four letters stood side by side: laos.

A few weeks after that, there was some commotion in the class. All the girls showed up wearing different variations of pink and the boys had on dark suits and little knotted ties. Miss Choi, the grade 1 teacher, was wearing a purple dress, dotted with a print of tiny white flowers, and shoes with little heels. The child looked down at what she was wearing. She was out of place in her green jogging suit which had been bought at Honest Ed’s, that place with all the flashing lights where they lined up to get a free turkey for Christmas. The green was dark, like the green of broccoli, and the fabric at the knees was a few shades lighter and it took their shape even when she was standing straight up. In this scene of pink and sparkles and matching purses and black bow ties and pressed collars, she saw she was not like the others.

Miss Choi noticed the green the child was wearing and her eyes widened. They calmly blinked, always scanning the room for something out of place, and when she spotted something she didn’t like her eyes got like this. All big and alarmed. She came running over and said, ‘Joy. Did you get your parents to read the note we sent home with you?’

‘No,’ she lied, looking at the floor where her blue shoes fitted themselves inside the space of the square of a small tile. Now, she didn’t want to lie, but there was no point in embarrassing her parents. The day went as planned. And in the class photo, the child was seated a little off to the side, with the grade and year sign placed in front of her. The sign was always right in the middle of these photos, but the photographer had to do something to hide the dirt of her shoes. Above that sign, she smiled.

When her mother came to get her after school she asked why it was all the others were dressed up this way, but the child didn’t tell her. The child lied, saying, to her mother, ‘I don’t know. All of them are out of their minds, thinking they could be fancy on an ordinary day. An ordinary day! It’s all it is. Don’t you pay your mind to them. Not one second!’

The child came home with a book. It was for practice, to read on her own. The book the child was given had pictures and a few words. The picture was supposed to explain a little bit about what was going on with the words, but there was this one word that didn’t have a picture. It was there by itself, and when she pronounced each letter, the word didn’t sound like anything real. She didn’t know how to pronounce it.

After dinner, the three of them sat down together on the bare floor, watching television side by side. From behind, the child looked like her father. Her hair had been cut short in the shape of a bowl. The child’s shoulders drooped and her spine bent like there was some weight she was carrying there, like she knew what a day of hard work was all about. Before long the television pictures changed into vertical stripes the colour of a rainbow, and her parents stumbled into bed. Most nights, the child followed, but tonight she was bothered by what she didn’t know and wanted to know it. She opened the book and went looking for that word. The one that didn’t sound like anything she knew.

That one.

It was her last chance before her father would go off to bed. He was the only one in their home who knew how to read. She brought the book to him and pointed to the word, asked what it was. He leaned over it and said, ‘Kah-nnn-eye-ffff. It’s kahneyff.’ That’s what it sounded like to him, what it was.

It was the next day that all of this was to come out. What this word was. Miss Choi gathered the whole class together. They all sat around the green carpet at the front of the room while the desks were left empty, and she would get someone to read. Someone would volunteer or she would point at someone, and on this day Miss Choi looked around and found the child. ‘You, Joy, you haven’t read yet. Why don’t you get your book and read for us.’

The child started and went along just fine until she got to that word. The one that didn’t sound like anything she knew. Miss Choi pointed to it and then tapped at the page as if by doing so the sound would spill itself forth. But the child didn’t know and there was no one to ask. Tap. Tap. Tap. Finally, a girl in the class called out, ‘It is knife! The “k” is silent,’ and rolled her eyes as if there was nothing easier in the world to know.

This yellow-haired girl had blue eyes and freckles dotted around her nose. This girl’s mother was always seen after school honking in the parking lot in a big shiny black car with a ‘v’ and a ‘w’ holding each other inside a circle. Her mother owned for herself a black fur coat and walked in heels like it was Picture Day every day. And sometimes it would be her father there. He was no different. Always honking on about something too. This girl read loud and clear. She never stopped to account for the spaces between the words. It was like something she knew by heart. And every time this girl volunteered to read, what she read came out perfect. They all tried and many had come so close. One or two errors could mean not seeing Miss Choi’s red velvet sack with all the prizes in it. For this girl, the sack always appeared. On this very day the prize was a red yo-yo. A red yo-yo! It was grand. There had been others before: a pencil, a pack of chewing gum, a lollipop, even a sack of marbles. But none had been as lovely as this red yo-yo. And had the child known what that word was, that red yo-yo would have been hers, but, of course, all of it would remain locked in the top drawer of Miss Choi’s desk now.

When the school day was over, the child gathered up her things. All that she had fit into a white plastic grocery bag. Now, for some reason, Miss Choi was waiting for her near the door and when she got there she asked the child to follow her to the front desk. There, she unlocked the top drawer and pulled out the red velvet sack. ‘Pick one,’ she said. And the child reached inside and pulled out a paper thing. It was a puzzle with an airplane in the sky.

Later that night, the child does not tell her father the ‘k’ in knife is silent. She doesn’t tell him about being in the principal’s office, about being told of rules and how things are the way they are. It was just a letter, she was told, but that single letter, out there alone, and in the front, was why she was in the office in the first place. She doesn’t tell how she had insisted the letter ‘k’ was not silent. It couldn’t be and she had argued and argued, ‘It’s in the front! The first one! It should have a sound. Why isn’t there a sound there?’ and then, she screamed as if they had taken some important thing away. She never gave up on what her father said, on that first sound there. And none of them, with all their lifetimes of reading and good education, could explain it.

And later, at home, the child looked over at her father. How he picked up each grain of rice with his chopsticks, not dropping a single one. How he ate, clearing everything in his bowl. How small and shrunken he seemed. She thought of what else he didn’t know. What else she would have to find out for herself. She wanted to tell her father that some letters, even though they are there, we do not say them. But decided, now was not the time to say such a thing. Now, the child said nothing. She told her father only that she won something, this thing, and showed him the prize. He did not know what it was she could have won. He is delighted because, in some way, he has won it too. They take the prize, all the little pieces of it, and start forming the edge, the blue sky, the other pieces, the middle. The whole picture, they fill those in later.

Photographs courtesy of the author