My father was the priest of a congregation that on a typical Sunday numbered no more than fifteen. Three of them were in the choir: two sisters in their eighties, who had argued fifty years ago and never spoken since, and my mother, who sat between them, wearing something soft to absorb the anger and bitterness on either side. The sisters weren’t the only ones to fall asleep during my father’s sermons, which were generally regarded as being too complex, ranging over questions of moral philosophy and scientific research and sometimes barely touching on God. People in the village thought of him as ‘an intellectual’ and he could cut a lonely figure striding across the bridge back towards our house in his cassock, with my mother and me following behind. At the back door there would always be some fumbling over keys. My parents never used to lock it, but after a spate of burglaries in the area they had started using keys and an alarm. Then into the dark corridor my father would plunge, skirts flapping, with just a few seconds to tap the right code into the alarm before it set off a wailing siren. The code was 1662, the publication year of the Book of Common Prayer. It was my father’s code for anything that required a four-digit number (he didn’t expect thieves to be theologians). In many ways it was his code for life, too.

My father’s relationship with the Church of England was difficult, for reasons I never fully understood, though I learned from an early age that bishops weren’t to be trusted. I think he saw the Church’s upper echelon as too distant and contemptuous of the lower ones. He had been treated dismissively at some point in his career and never forgot the slight. The Book of Common Prayer, which he loved, cut out those fractious middle men and spoke straight to God.

The prayer book is largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Henry VIII and driver of reformation in the English Church. It was published in 1549, with a revision in 1552 and another in 1662 – having been banned for a time under Oliver Cromwell. If you believe that words shape a national identity then Cranmer, like William Shakespeare, is an architect of the English character. There is a rhythmic beauty to his translation that still resonates in the way we speak and write. In The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography, Alan Jacobs describes how Cranmer’s language stays close to the concerns of ordinary people and their fears about life and death, darkness and illness. He uses pairs of words where sometimes in the Latin there was only one: ‘we have erred and strayed from your path like lost sheep’, ‘we have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts’. He often uses alliteration, and repetition, and prefers words of Anglo-Saxon origin. For the writer and theologian C.S. Lewis, the original Latin phrases were ‘almost overripe’, but the English of the prayer book ‘arrests them, binds them in strong syllables, strengthens them even by limitations, as they return erect and transfigure it. Out of that conflict the perfection springs’. For Samuel Johnson the words provide ‘equitable balance when we ourselves have none’.

We certainly had need for that equitable balance. When I was a teenager my brother committed suicide, which sent our family reeling in different directions from the grief. A bereavement following suicide too often divides the family left behind instead of uniting it. By that time, my father had stopped working for the Church full-time and was running a small farm. Farming turned out to be frustrating too, but at least then the weather was to blame, rather than the bishops. You can kick a tractor wheel or a sticking door. You can’t kick a bishop and get away with it.

When my brother died I would have liked my parents to roar and weep and for the four of us – I had a sister, too – to cleave together in our grief. But my parents, who had been children during the war, were stoic in a way that is nowadays never seen as virtuous but only as a caricature of English repression. Their stoicism maddened me and seemed like an inadequate response to what had happened. It was decades before I began to see how their pain had been contained in the words they spoke at church. For them, the liturgy really had the power to comfort and heal. To speak aloud in the presence of others the same words that have been spoken by centuries of forebears was not, as I thought then, a meaningless lip service, but a deeply felt rite.

In any case, we were a wordy family, and not just in church. At mealtimes there would be debates about what words meant and where they came from. Books would be brought to the table. The Oxford English Dictionary was more often in the kitchen than anywhere else. My father often returned to Cranmer and the power of his language. Sleeves rolled up, strong forearms on the table, he wasn’t averse to thumping the table if his argument called for it. He explained how the prayer book was born out of political necessity: after Henry VIII’s break with Rome, the English church needed a new liturgy, while the monarchy wanted to forge a common identity and stamp out Catholic resistance. Cranmer’s aim was to provide a regular form of worship that united all people in a language they could understand. Congregants at a Latin Mass often grasped nothing of what was being said. Their main reason for going to church was to see the priest hold up the wafer proclaiming ‘Hoc est Corpus Meum’. That was just ‘hocus pocus’, some people complained, nothing better than a magic show. If you followed the new doctrine, you should regard this as merely a symbolic reference to the Last Supper. But it was clear that many worshippers still clung to Catholic ideology, seeing it as at the moment of transubstantiation, the actual conversion of bread and wine into body and blood.

Cranmer – who had held Henry VIII’s hand as he lay dying, but not administered the last rites – pushed his reforms harder under Edward’s VI’s reign and on Easter Sunday 1548, the English order for Communion became mandatory throughout England, marking a radical change in national life. Catholics had lost their rituals; Puritans felt cheated of a chance for greater reform – they would have banished bowing, kneeling, altars, garments and symbols. Opposition never went away, but over time the new regime prevailed, and a rhythm of worship was instituted that joined everyone in morning and evening prayer and made Holy Communion a weekly focus for all. It was Cranmer’s specific injunction that the congregation respond together to the priest, who must speak ‘with a clear loud voice, that they may be plainly heard of the faithful people.’

That congregational response accompanied all the Sundays of my childhood. When I stood to make the responses in church, it was among people that I knew. Without turning round, I could pick out their voices: Toby, the baritone, who always sang the descant, whose wife hated village life and had left him for an estate agent; Sandra, who ran the shop, whose daughter alienated my parents by chewing gum when she came to the house collecting money for a sponsored run. Margaret, who had cut off all her hair when it became too difficult to manage and turned it into a wig which sat at a jaunty angle on the top of her head. When you hear people speaking the same words week after week, you grow attuned to their peculiar tics and intonations, you know which voices will strain to reach higher notes, which sound peevish or insincere. Occasionally we sang the psalm instead of speaking it. The organist would give us a note (after her retirement there was no organist, just someone pressing buttons on a cassette player) that was always an octave too high. While I found it crushingly dull to speak the psalm, there was a roller coaster appeal in singing it – the way you had to slide so many words onto one note, ‘it-is-He-that-hath-made-us-and-not-we-ourselves-We-are-His-people’, – before the swooping into an unlikely ending ‘and the she-ep of his pasture’.

Otherwise I hated church. It heralded a day dominated by homework and heavy food, with no excitement until The Six Million Dollar Man at night. As a child I tried to get out of it altogether, lying under my parents’ bed with hands reaching for me from both sides. I dreaded the moment when the children in the congregation would be invited to go into the vestry for Sunday School. Why didn’t I go with them? It would have meant avoiding the sermon – a lucky escape. My mother couldn’t understand my reluctance and I could hardly explain it myself when I saw the little models of flat-roofed houses they built there, like the ones in Jerusalem, and the mosaic pictures of Mary made with tiny pieces of coloured paper. I was very shy, though, and I wanted to stay beside my mother, whose every utterance in church I knew by heart, especially that sad, compelling riddle – ‘We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; And we have done those things which we ought not to have done’. I felt that wasn’t fair: she was doing her best.

Increasingly, the services we went to used the Alternative Service Book, a simplified and updated set of prayers authorised for use by the Church of England in 1974. My parents hated the ASB. It was ‘banal’, they told me, long before I knew what ‘banal’ meant.

Now, when the priest intoned ‘The Lord Be With You’, instead of saying ‘and with thy spirit’, we said ‘and also with you’, which sounded both coy and awkward, a knee-jerk response to an unexpected compliment. It seemed so much less mysterious to believe in things that were ‘seen and unseen’, as they were in the Alternative Service, than in things that were ‘visible and invisible’, as they had been in the Book of Common Prayer. ‘Trespasses’, which used to set off a sibilant ripple through the congregation, had been flatly replaced with ‘sins’. The priests themselves were uninspiring – pompous or simpering, with an earnest over-bite or a hand that smelled of Palmolive when it rested heavily on my head at the time of the Blessing. One had a big red face and smelled of whisky. Another was paranoid, delusional, or both. He had excommunicated a woman who disagreed with him in a parish council meeting and then, when everyone assumed this to be a tasteless joke, turned his back on her at the altar rail in front of the whole congregation. Next he went for a young couple who had to cancel their marriage preparation class when their sheep broke through a fence and ran onto the road. He could have offered to help round up their strayed and erring sheep – it would have been a wonderful allegory – but no: he excommunicated them, too. No wonder my father got so irate with the Church.

On Christmas Eve, we watched the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols broadcast from King’s College Cambridge. This may have been the same year that my mother bought a turkey that was too big for the oven and my father tried kicking the tray, which buckled and got wedged in the runners. Though there was also a year when our dog ate the turkey, before it had even got as far as the oven, and then threw it up again in the kitchen. At any rate, tensions were running high. And things could only get worse with the reading from John, chapter one, the climactic ninth lesson. It was going to be badly done – we all knew that. I used to feel a nervous excitement as the provost made his way to the lectern and prepared to read.

‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’

‘Did you hear that?’ my father said. ‘The word was with God, and the word was God. They always get the stresses wrong. What is important here? It’s not was or with, it’s God, it’s the Word!’

*

The words were important to my father, no doubt about that, but I was less sure about his views on the Word. His faith ran deep and its reflection on the surface could seem indistinct. He didn’t believe in the Virgin birth, in miracles, or in Heaven and Hell as places distinct from the earthly world. He strongly believed in the concept of a God-given soul, but not, I think, in its continuance after death. At home, we more often spoke about theology than faith and, like many buttoned-up Anglicans, we were embarrassed by people who were openly devout. My father said he hoped I would never bring home a ‘very religious’ boyfriend. ‘Don’t you long to spread the Good News?’, an eager friend once asked me at university. No, I definitely didn’t. I thought of religion as something private, though I began to see how perverse that idea was in the context of a growing evangelical movement.

A lot of church-goers, it seemed, didn’t love the prayer book the way my father did. Those words I had been brought up to see as encapsulating the mystery of faith, other people saw as an obstacle to it.

Alan Jacobs identifies World War I as the time when moves to reform the prayer book gathered pace. Chaplains returning from the Front pushed for a liturgy that soldiers could understand. Cranmer had written at a time when people’s lives were so different. Seventeenth century men and women feared the dark and the malign effect of the moon or night air. They worried with good cause that none of their children would survive infancy. Not only had ordinary life changed beyond recognition, but the language was now too arcane to be understood by many in the congregation, or no longer meant what it once had. It made no sense to use ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ in church when you didn’t use it anywhere else. It felt so much worse to call yourself a miserable offender in the twentieth century than in the sixteenth, when ‘miserable’ had simply meant ‘deserving of mercy’.

How could Cranmer be revised, though, except with writing that was equally beautiful and on which both Church and state could agree? It proved – and continues to prove – to be an impossible task. When the Church of England tried to make very small adjustments to the Book of Common Prayer, the House of Commons voted against them in 1927, and again in 1928, in chaotic scenes that made the front pages. It was another forty years before the Church found a way around the political impasse with the Alternative Service Book, so called because it made no claim to be the official prayer book and therefore did not require parliament’s approval. The ASB, and its successor Common Worship were eventually adopted by most English churches, but for many, eloquence had been sacrificed for the sake of simplicity – even banality. Meanwhile, the unrevised 1662 Book of Common Prayer kept its place as England’s official prayer book.

Its admirers would fight to keep it there. When a priest in a New York parish tried out new rites, one member of the congregation, the poet W.H. Auden, wrote to ask if he had ‘gone stark raving mad?’ Auden wrote:

Our Church has had the singular good-fortune of having its Prayer-Book composed and its Bible translated at exactly the right time, i.e., late enough for the language to be intelligible to any English-speaking person in this century (any child of six can be taught what ‘the quick and the dead’ means) and early enough, i.e, when people still had an instinctive feeling for the formal and ceremonious which is essential in liturgical language . . . I implore you by the bowels of Christ to stick to Cranmer and King James. Preaching, of course, is another matter: there the language must be contemporary. But one of the great functions of the liturgy is to keep us in touch with the past and the dead.

The battle lines were drawn. Arguments for and against liturgical reform seemed so difficult – and yet so necessary – that when the Archbishops of Canterbury and York began talking about revising the psalter in the 1950s, it was with the weary joke that perhaps they could have it ready for the millennium. Miles Coverdale’s psalms were a much loved component of the Book of Common Prayer, but experts agreed that his translations from Hebrew were not entirely accurate. ‘A sound modern scholar has more Hebrew in his little finger than poor Coverdale had in his whole body’, said C.S. Lewis.

A Commission to Revise the Psalter was formally announced, and alongside the clergy, Hebrew scholars and musicians sitting on it there would be ‘two scholars of English.’ Lewis’s recent study, Reflections on the Psalms, recommended him as one of them. The other scholar was someone Lewis openly disliked, describing him as ‘the single man who sums up the thing I am fighting against.’ That man was the poet T.S. Eliot.

Lewis had publicly attacked Eliot as a writer, as a theologian, even – in a letter to the journalist Paul Elmer More, as a foreigner. ‘Eliot stole upon us, a foreigner and a neutral, while we were at war – obtained, I have my wonders how, a job in the Bank of England – and became (am I wrong) the advance guard of the invasion carried out by his natural friends and allies, the Steins and Pounds and hoc genus omne, the Parisian riff-raff of denationalized Irishmen and Americans who have perhaps given Western Europe her death wound.’

In 1945 their mutual friend Charles Williams had arranged a reconciliatory meeting between the two men at a hotel in Oxford, but it had not gone well. Eliot’s first remark is said to have been: ‘Mr Lewis, you are a much older man than you appear in photographs!’

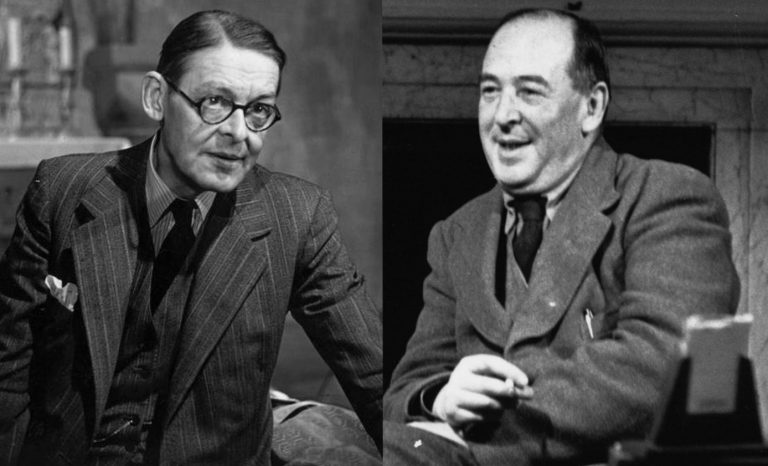

Given how many others had floundered and failed in their attempts at prayer book revision, the prospects for such an antagonistic pair didn’t look promising. Lewis was expected to play the traditionalist on the committee, with Eliot offering a modernist counterweight. They dressed the parts at any rate, the chairman, Donald Coggan describing the sartorial contrast as ‘startling’. ‘C.S. Lewis would come dressed in country tweeds, looking like an old red-faced countryman with a stick, and with a bag of books slung casually over his shoulder.’ T.S. Eliot, meanwhile, ‘would arrive from a very different world, a dark-suited, select gentleman from the City of London, with a rolled umbrella.’

And yet, far from conforming to type, the men seemed to swap roles. Lewis was the most open to the idea of change, describing as ‘absurd’, in a letter to a friend, ‘the impulse to retain what we know to be mere howlers because they are “so beautiful”.’

Meanwhile, minutes from their meetings at Lambeth Palace reveal Eliot as the more conservative of the two, constantly vetoing changes proposed by others. ‘I should like to retain the archaisms’, he remarks.‘Why alter the old spelling, “shew”. I like it’ and, ‘The tenses here of Coverdale do not bother me’. His wife Valerie recalled him coming in late one night from a meeting of the commission ‘and when I asked him how it had gone, he said with a tired grin, “Well, I think I’ve saved the Twenty-Third Psalm”.’

T.S. Eliot and C.S. Lewis

So obstructive was Eliot in fact, that when the revision was finally completed a fellow committee member argued against using his name to help promote it. ‘Mr Eliot’s positive contribution to the Revised Psalter was nil. He had spent his whole time resisting any change!’

Perhaps the lesson was that if you want help modernising poetry, you shouldn’t ask a modernist poet. Ten years later, W.H. Auden would be similarly reluctant on another committee to revise the psalms, this time for Americans. His changes amounted to a word here or there – ‘secrecy’ for ‘secret place’; ‘cataracts’ instead of ‘water-pipes’ – otherwise he stuck to the view that prayer book revision was ‘the fad of a few crazy priests. If they imagine that their high jinks will bring youth into the churches, they are very much mistaken.’

The Anglican commission did finally authorise a raft of changes to Coverdale’s psalms, despite the poets’ objections and sometimes in the teeth of their resistance. But perhaps the biggest revision to take place at the Lambeth Palace meetings was on the relationship between the men themselves, their mutual esteem growing to the degree that, not long before he died, Lewis told his private secretary, ‘You know I never liked Eliot’s poetry, or even his prose. But when we met this time I loved him’. And of his work on the commission he wrote, ’we were a wonderfully happy family. I have seldom enjoyed anything more.’

*

The bank manager was young, tall, perfunctory. The language of loss lay outside his remit. ‘In a minute I’m going to connect you to someone from the Sympathise Team’, he said, passing me the phone. ‘They’ll sympathise with you, then take you through some security questions.’ A woman came on the other end of the line. A pleasant voice said, ‘Good morning. I’d like to start by offering you my condolences.’

I didn’t blame her or the bank manager for thinking they could encompass the difficult emotions a bereavement brings simply by invoking a word – though ‘Sympathise Team’ did have the ugly ring of something conjured by a management consultant. The shorthand freed us from a difficult conversation, and closing down my father’s bank account was the least painful part of wrapping up his affairs. He had been unwell for several years, never really recovering from a heart operation that had been followed by pneumonia and a week in an induced coma. During those days my mother sat by his bed every day, reading to him from the Book of Common Prayer. It was terribly sad to see my father lying unconscious, his hair raffishly tousled by wind from a fan, with my mother holding her prayer book beside him.

Soon after he was brought round again, he began to try speaking. My mother, sister and I placed chairs beside the bed. Quietly my father mumbled a few words we didn’t catch. Then he said:

‘Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! the Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light.’

We looked at each other in bafflement. It’s a great relief to hear someone you love speak again after a long silence, but also alarming when you have no idea what they’re talking about.

‘Dreaming when Dawn’s Left Hand was in the Sky

I heard a Voice within the Tavern cry,

“Awake, my Little ones, and fill the Cup

Before Life’s Liquor in its Cup be dry.”

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted – “Open then the Door!

You know how little while we have to stay,

And, once departed, may return no more.” ’

And so he went on with a recital that, though probably not perfect, sounded unnervingly fluent to us. It was my mother who recognised the verses as coming from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám, a collection of poems translated by Edward FitzGerald and attributed to a Persian mathematician, a devout Sufi Muslim according to some accounts, and an agnostic or even an atheist according to others. I had never heard my father talk about the Rubaiyat. It wasn’t the kind of verse we would have expected from him.

‘I didn’t realise he knew so much of it,’ said my mother.

‘Perhaps he learned it at school.’

The poetry continued on and off, over the next day or so and while it was still unnerving, it was also better than the alternative, because when he wasn’t reciting the Rubaiyat my father’s other observations were heartbreaking. He said that he was being treated brutally in the hospital, that he was competing in an ‘olympics of cruelty’. Unfortunately there were many more weeks before he could come home, and although he did make a recovery of sorts, his health soon failed again, and he became increasingly confused. The easiest conversations to have with him were ones that included remembered poems and texts. My father, who was losing his once great intellectual powers, who was baffled by the simplest conversations, could still remember passages of Shakespeare or poetry. For a year we spoke in sonnets and soliloquies, songs and lines from the liturgy. The comfort he found in reciting verses made me reconsider the value of learning lines and speaking them aloud.

I thought back to my own school, to my class of ten girls standing on one side of the room and chanting Keats at the headmistress, who sat on the other side, her gaze lost in the sunlit garden. It used to seem as hollow and meaningless an exercise as the recitation of texts in church. But decades later, those lines of poetry often came back to me and I would find myself waiting for a bus, thinking, ‘the owl, for all his feathers, was a’cold / The hare limp’d trembling through the frozen grass, / And silent was the flock in woolly fold.’

Holding the words in my mind was deeply reassuring, like holding an old piece of fabric from a childhood quilt. I thought, if words were laid down like patterns, even before you were old enough really to understand them, perhaps they served as some sort of guard against future distress. Somewhere at the back of your mind they would be waiting, available for consolation later in life, if a time came when all was chaos and a pattern was needed to restore the equitable balance Johnson spoke of.

I found my father’s copy of the Rubaiyat, while packing up his library. He had hundreds of books and it was a big job to sort through them all – the sort of job a Sympathise Team might more usefully be put to work on. His collection included many works of religion, but also books on philosophy and psychology, R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self, for instance and Arthur Koestler’s The Ghost in the Machine (such a disappointment, as a child, to find out that it wasn’t actually a ghost story). My sister and I couldn’t take the books back home – we didn’t have room for them all – so most of the theology went to a specialist charity shop. Some paperbacks, falling apart in my hands, we took to the recycling centre. They can be used to make a paste that helps bind asphalt to tarmac. Much of the M6 toll road has been paved this way.

Among the books I offered to a dealer was the Imperial Bible which was so enormous I could barely lift it. Its lurid illustrations had frightened me as a child, and since there were no signatures in it, no personal connections, I thought this might be one to sell. The dealer wasn’t interested, though. ‘Sorry, but I get offered at least one of these a week and I just can’t shift them’, he told me, before looking up with a smile: ‘But they do make excellent insulation.’

Photograph © changingpaths