1.

In 1968 I had a crush on a girl who was frightened of the Post Office Tower. The girl, Melanie Kilim, aged ten, was the sister of my best friend, and even as an eight-year-old I understood this relationship to have the potential of something socially complicated. The crush passed and we went our different ways, but my friendship with her brother endured and I still see a good deal of him. Almost forty years have passed. We each have wives and children, and when I visit his house on a Sunday morning we talk of property prices and knee-joint trouble. It was because of other conversations during these visits that I knew his sister Melanie was still frightened of the Post Office Tower.

One evening in April 2005, when I had just turned forty-five, I called her up about it out of the blue. ‘Hi Melanie, this is Gus.’ Gus was my school nickname. ‘It’s been quite a while, but I want to ask you about something I’ve always wondered about . . .’ Melanie was forthcoming. She said her phobia began soon after the building went up in 1965, transforming and modernizing the London skyline. She thought her fear of it might have something to do with the robotic Daleks in the BBC serial, Dr Who, and with the memory of a man in a neck-brace she once saw in the local greengrocer in Golders Green. I thought it might have a more obvious explanation – something to do with the phallus and sex – but she dismissed this. She wasn’t nervous of any other tall buildings, only what she called this ‘grey-green monster’. She thought that the tower might suddenly jump out at her. She would turn a corner in Soho or Bloomsbury, and there it would be: ‘I think it might attack and strangle me – something to do with the neck again.’

To avoid this possibility, Melanie Kilim told me that she had developed an extraordinary sense of positioning and direction. She said there was no street in the tower’s vicinity where she didn’t know what she would see when she came around the corner. If this was to be the tower, she knew the perfect diversion. She told me that once, when she was visiting the Middlesex Hospital, only a few hundred yards from the tower, she had worn a blindfold to avoid an otherwise inevitable sighting.

The object that always repelled Melanie had always attracted me. As a boy, I was fascinated by it. It was new. It was statistically engaging. Out of the then generally flat London townscape, it rose astonishingly to 619 feet – the highest structure in London, nearly twice the height of the dome of St Paul’s. It weighed 13,000 tons and contained 780 tons of steel. It could handle 100,000 telephone calls simultaneously and boosted radio and television signals, bouncing the waves over the new London high-rises on to the home-county hills. Its two lifts travelled at 1,000 feet a minute, and if you took one to the top you could sit in the revolving restaurant which turned two-and-a-half times every hour, which meant that, if you were a Londoner, you didn’t have to wait too long to point to the streets that contained your own home. My father took me up to the top a few months after it opened, and I treasured the green plastic model he bought me at the gift shop. I still have it in a cupboard next to a plastic grouping of the Chimpanzees’ Tea Party from London Zoo.

For me, the opening of the tower marked not only the completion of a landmark, but the birth of something equally special – a commemorative postage stamp with a fabulous error on it. I first became aware of this in 1968 when a stamp magazine carried the news that less than one sheet of these errors had been discovered. About 55,500,000 of the stamps had been sold, but only about thirty of them had the mistake. I looked at a photograph of a stamp with the flaw – a printing glitch: it was captioned 1965 post office tower, olive-green omitted. To an eight year old, this was unbelievable. The only thing that was supposed to have been printed in olive-green was the Post Office Tower itself; the surrounding buildings were all there, but in place of the tower there was only white space. I thought then (as I thought again nearly forty years later), ‘This would be the perfect stamp for Melanie.’

2.

I’d like to think that every schoolboy collected stamps in those days, but I’m sure that even in 1968 it was a hobby that was falling away. What kind of boy was I, to have this love of stamps? Self-description is the hardest art, but some things can be said.

I was, I think, a quiet boy with no evident talents, and my main interest, apart from my basset hound (and until stamps arrived), was procuring sweets from a shop called Lollies. My room was covered with pictures of Chelsea footballers with tight shorts and crinkly hair, but I never had hopes of being a football star myself. I didn’t know what I wanted to be; certainly not an astronaut or fireman or anything heroic. I thought I might like to be a pop singer, but I imagined myself quite happy working behind the counter in a sweet shop or post office – perhaps in Hampstead Garden Suburb, the leafiest and most fashionable of London suburbs, where we lived in a very comfortable house among neighbours who also kept pets and had an aversion to noise after 7.30 p.m. Among people, in fact, like my father, a successful solicitor in the City who drove a soft-top Triumph, played golf, smoked cigars, took me sometimes to synagogue on a Saturday morning, and wished me to do better in school. He was a generous man but he didn’t like noise or unruliness and I could stir him to rare anger by breaking a window with a tennis ball. My brother was almost five years older, effortlessly skilled at maths and science, and fast enough as a bowler to practise with junior teams at Lord’s. I once broke his arm wrestling on the carpet, but usually (both before this event and after) we had little to do with each other. My mother looked after us all, occasionally helping in local old-peoples’ homes and entertaining friends with Robert Carrier’s Classic Great Dishes of the World. This life was all I knew, and it seemed ideal. I remember walking back from school with a fellow pupil called Will Self, who had still to discover drugs or novel writing, and learning that he was about to go on holiday to the Seychelles. I had no idea what or where that was. I hadn’t yet experienced abroad; my parents went on foreign trips together, leaving my brother and me in the formidable charge of a Mrs Woolf, who wouldn’t let us drink water with our meals because it filled us up. The most daring thing I did was have my hair cut by a man in flares called Paul whose salon was called Unisex, a word the entire neighbourhood found exceptionally unsettling. Stamp collecting, that most quiet and respectful of pastimes, was something that all of my neighbours and parents’ friends would have approved of; it offered no evidence of nonconformity, noisy childish rebellion or the budding turmoil of sex. The postage stamp is a silent thing, and an emblem of social order rather than its opposite.

I can’t say precisely when I got interested in stamps. As for why, that may be as unknowable as the causes of Melanie Kilim’s fear of the Post Office Tower. But by the time I was eight they had me in their grip; in their grip and also, quite soon, slightly ashamed of their grip. I remember feeling sheepish about telling my friends of my interest. The first time I entered my school’s annual philatelic competition (which, for the winner, meant a prize on Speech Day, enabling some people in the hall – perhaps my parents – to believe the prize had something to do with academic merit) I was not at all surprised to learn that the other entrants were the sort of boys I looked down on – the friendless, the ungainly. I didn’t envy their lives, but I did envy their stamps: one boy, also called Simon, had a small collection of King George V ‘Sea Horses’, high-denomination stamps that, although postally used and not ‘mint’, were probably worth a hundred pounds. I think he had been left them in a will, something that as far as I knew would never happen to me. For the school competition one year I put together an elaborate story inspired by the British Wild Flowers set of 1967, describing each of the flowers in turn and where they grew. I think I listed some varieties I had seen in magazines, such as ‘missing campion bloom’. The other Simon mounted his Sea Horses on clean album pages, labelled them ‘George V Sea Horses, 1913, 2s 6d, 5s, 10s and £1’, and won. I think the teacher who judged, probably a collector himself, thought the other Simon’s stamps worthy of space in his own collection, whereas he probably had my flowers as full sheets, ordinary and phosphor (the phosphor was an innovation to aid automatic sorting).

I confess that I thought for a minute about stealing the other Simon’s stamps. Not because I wanted them, but because I wanted him to be unhappy. The thought quickly passed: I’d be found out, I’d be expelled from school, I’d still feel unsatisfied. It was probably at this point that I came to terms with one of the great universal philatelic truths: no matter what you have in your collection, it isn’t enough. You could collect all the Queen Elizabeth issues, but there would be new ones every few weeks, and a gnawing feeling that there were some rare shades or misperforations you didn’t yet have. And could you really call yourself a collector if you didn’t have something or everything from the Cape of Good Hope and the British Commonwealth? In this way stamps taught me about setting boundaries and limiting one’s ambitions – about life, really – but unfortunately this knowledge didn’t quell the overriding desire to obtain more stamps.

Occasionally I would buy cellophaned packs from the newsagents W. H. Smith which cost a few shillings and promised to contain stamps with a catalogue value of £5 or £10. This told even an eight year old that catalogue values were not to be trusted. Some packs came with plastic tweezers and a plastic magnifying glass, so that a beginner could pretend to be a pro, much like a child turning a fake plastic driving wheel in the back of a Ford Consul. But it was laughable to imagine that the magnifying glass would actually discover anything interesting in such a cheap pack of stamps; the tweezers were redundant, too, as you could have handled the stamps with treacle on your fingers and not reduced their value further. The best stamps were the ones that came free on envelopes through the letter box. Franking machines were not yet in every office; secretaries were dispatched to buy 200 stamps at a time, and even the most official mail had a colourful corner. The stamps could be detached from their envelopes with the steam of a kettle or by being placed in warm water and then dried on a newspaper, and they filled a lot of album space.

Then there was this system called ‘approvals’, the idea being that you sent away for stamps ‘on approval’ and only once you had received and ‘approved’ them did you send on the postal order as payment. In theory, I suppose, you could have approved some stamps and kept them and rejected others and sent them back, haggling with the dealer about how much was owed; or that, at least, may have been the implication in the advertisements which appeared regularly in boys’ magazines. But when I sent away for a packet of approvals I had no idea what that word meant – only that the prospect of receiving expensive-looking stamps for no outlay was appealing. The packet I received did not contain especially good stamps, a lot of them being Victorian issues with heavy cancellations. I think one of them was a Penny Black, the world’s earliest gummed stamp first issued in 1840, but it was probably a stamp with one or no margins, an example of which sat proudly at the beginning of every schoolboy’s album, worth hardly anything compared with a three- or four-margined example. (In the days before perforations, the margin showed where a stamp had been cut from the sheet, and the postmaster doing the cutting had no concern for posterity – which explains why a used strip of six Penny Blacks with excellent margins recently sold at auction in London for £90,000.) One month after my free stamps arrived, there was a follow-up letter. ‘We are delighted you have chosen to accept the full card of stamps. The total is £3 15s.’ My father sent a cheque, and stopped my pocket money for a while. I think the stamps are now worth about seventy-five pence.

Eventually, when I was twelve, I discovered the adult world of stamps and the dealers who had their premises on or near the Strand. The trips took place on a Saturday afternoon and at first I was accompanied by Aunt Ruth and her old dachshund, to make sure that nothing untoward happened to me on the streets of central London. But soon enough I was wandering by myself through the market underneath the railway arches by Charing Cross Station and then to the many stamp shops near the Aldwych and Covent Garden. At the market I could afford a few space fillers and commemorative issues that had appeared before I started collecting, and I bought secondhand magazines for a few pennies each. Stamp magazine contained articles headlined postmarks, places and people and international reply coupons – new designs! There were also articles specifically for beginners, explaining the meaning of philatelic terminology such as ‘tête-bêche’ (two or more joined stamps, with one upside down), and advice on how to look for priceless stamps on old documents in your grandmother’s loft. This would have been fine if grandfather hadn’t got there first, and sold anything half-decent to dealers or friends. By the time I began collecting in the 1960s, the world had got wise to the value of stamps. Philately was more than 120 years old, and lofts had long given up their treasures.

3.

Men and women began collecting stamps in 1840, the year stamps first appeared, but nobody then could have imagined the cult – the industry – it would become. Sheets of Penny Blacks and Twopenny Blues contained 240 stamps and, to limit forgeries and to enable the tracing of portions of a sheet, each stamp had a letter in the two bottom corners. The rows running down the sheet had the same letter in the left corner, while the right corner progressed alphabetically. The first row went AA, AB, AC and so on, and thirteen rows down it went MA, MB, MC . . . There were twenty horizontal rows of twelve, so that the last stamp at the bottom right-hand corner was TL. People who got a lot of post thought it would be fun to collect the set.

One of the first mentions of the new hobby appeared in a German magazine in 1845, which noted, much in the manner of comedian Bob Newhart describing Raleigh’s attempt to promote tobacco, how the English post office sold ‘small square pieces of paper bearing the head of the Queen, and these are stuck on the letter to be franked’. The writer observed that the Queen’s head looked very pretty, and that the English ‘reveal their strange character by collecting these stamps’. The first collector history is aware of was a woman known only as E. D., who is identified in an advertisement in The Times in 1841: ‘A young lady, being desirous of covering her dressing room with cancelled postage stamps, has been so far encouraged in her wish by private friends as to have succeeded in collecting 16,000. Illese, however, being insufficient, she will be greatly obliged, if any good-natured person who may have these (otherwise useless) little articles at their disposal, would assist her in her whimsical project.’ There were two addresses to send the stamps, one in Leadenhall Street in the City, one in Hackney. There are no further records of E. D.’s collection, nor are there pictures of her room, which must have been a shade on the dark side with its walls of Penny Blacks, Twopenny Blues and the new Penny Reds of 1841, and would surely have put E. D. among the ranks of Young British Artists in the next century. The following year, Punch noted that ‘a new mania has bitten the industriously idle ladies of England. They betray more anxiety to treasure up the Queen’s heads than Harry the Eighth did to get rid of them.’

By the mid-Victorian period, stamp collecting had become a small craze among public schoolboys, prefiguring many later crazes – collecting locomotive numbers, Batman cards, Pokemon – which have turned school playgrounds into centres of scholarly pursuit, abstruse to parents. S. F. Cresswell, a master at Tonbridge School in the late 1850s, informed the periodical Notes and Queries that a boy had shown him a collection of between 300 and 400 different stamps from all over the world, and wanted to know if there was a guidebook available which listed all known stamps, and a place in London where one might buy and exchange them. Subsequent issues of Notes and Queries offered him no help, but Cresswell was only slightly ahead of his time, as we know from the first history of the hobby, a book called The Stamp Collector by William Hardy and Edward Bacon, published in 1898. Hardy and Bacon listed the large number of philatelic societies that had sprung up since S. F. Cresswell had first looked for them forty years before. There was the Stamp Exchange Protection Society of Highbury Park, London, the Cambridge University Philatelic Society, and the Suburban Stamp Exchange Club of St Albans, Hertfordshire. There were also societies in Calcutta, Melbourne, Ontario, Baltimore and Bucharest. Hardy and Bacon identified the key moment that always defines the coming of age and validation of any serious collecting hobby: the publication of a catalogue. This told a collector that they were not alone, and it set the boundaries of a collector’s ambitions. This moment came in 1862 with The Stamp Collector’s Guide: Being a List of English and Foreign Postage Stamps with 200 Facsimile Drawings by Frederick Booty, which begins with the observation that ‘Some two or three years ago . . . collectors were to be numbered by units, they are now numbered by hundreds.’

When Hardy and Bacon’s book was published, Bacon was a member of the Expert Committee of the Philatelic Society (London) for the Examination of Doubtful Stamps (by the end of the nineteenth century philatelists were already a target for forgers). But some years later he acquired another role in which this expertise was more than usually vital: he became Curator of the Collection of King George V, charged with the growth and care of the most significant and valuable stamp collection in the world. The roots of George V’s obsession are no more amenable to reasoned inquiry than mine or Melanie Kilim’s, though personal vanity may have played more of a part (few collectors get to appear in their own albums). He was certainly a most determined collector. In February 1908, when he was still the Duke of York, he wrote to a friend about the purchase of some stamps from Barbados: ‘Remember, I wish to have the best collection & not one of the best collections in Britain, therefore if you think that there are a few more stamps required to make it so don’t hesitate to take them . . .’ As king, and when not on tour or at his country residences, he devoted four hours of every day in London to his stamps, and he regularly showed choice items at the big exhibitions, but his zeal was not universally shared by his courtiers. After he spent £1,450 on a mint Two Pence Post Office Mauritius specimen, one of his staff unknowingly asked him whether he had seen that some ‘damned fool’ had paid so much for a single stamp. When he died, his British Empire collection comprised 350 volumes and it has since been augmented, with slightly less enthusiasm, by his son and granddaughter, George VI and Elizabeth II.

George V’s principal inspiration – ’the man to beat’ – was Thomas Tapling, MP, who amassed almost every stamp in the world between 1840 and 1890, when such a thing was still possible. The Tapling Collection is thought to be the largest private nineteenth-century collection still intact, and many of the rarest specimens are errors – wrong colours and inverted heads. Among the rare Barbados stamps that George V bought was the 1861-1870 One Shilling printed in blue rather than the intended brownish-black. Twelve copies are known, one of them in the Tapling Collection. But Tapling’s achievement was greater than a painstaking gathering of wonderful stamps. He also inspired more collectors than anyone else, George V being simply the most famous. The visitors who today pull out examples from Tapling’s collection in their sliding cases at the British Library can only marvel at the gems on display, and perhaps feel a little envy. For there will never be another collection like Tapling’s. Unless the British monarchy decides to part with the hundreds of albums stored in the St James’s Palace Stamp Room, no single collector could hope to acquire such a magnificent variety of stamps in a lifetime.

How was it done? With money. If the first key moment in the validation of a collecting hobby is the catalogue, then the second is the value of the things collected: their quoted price in the market. Both Tapling and the king bought some of their collection from Stanley Gibbons, the man who became to stamps what Berenson and Duveen are to painting, the founder of what is now the world’s oldest stamp company, an institution in the Strand since 1893. Edward Stanley Gibbons began collecting in his early teens, entranced by the romance of the stamps that reached his home town, the port of Plymouth, on mail from overseas. (By the time he began trading out of his father’s chemist shop in 1856, more than twenty other countries had also begun issuing postage ‘labels’.) His big break came in 1863 when a couple of sailors sold him a large quantity of triangular Cape of Good Hope stamps they had won in a raffle. He bought them all for £5 and with the profits from their resale he greatly expanded his stock. He published his first price list in 1865, three years after Booty’s catalogue, and his clientele, including many doctors and barristers, were reported to have been taken aback by his high charges. How was it that a tiny piece of paper decorated with a mechanically-reproduced picture could be worth three guineas when only a few years earlier it could be had from a post office for threepence? And could such a question be answered by the simple statement that, as with gold, value depended on quality, rarity and demand?

Gibbons died in 1913, presumably content that his name was associated throughout the world with exhaustive stock and overwhelming prices. Long after his death his shop in the Strand was infused by the kind of atmosphere you might find in a West End establishment that sold game-shooting guns or fine claret to gentlemen. It was an imposing and patronizing place and when I first went there, in the 1970s, I felt nervous even asking for a new pack of hinges. ‘And what can we do for the young master today?’ I had a stammer. I wanted to look at their stock, but my stammer overwhelmed me (like many stammerers, I found that the hardest words to say were those beginning ‘st’, such as stock and stamps). ‘Just looking,’ was all I would usually manage. I received a warmer welcome in the smaller and more chaotic shops nearby, though the dealers who owned them could never have anticipated a big sale. I hardly ever bought anything, principally because I couldn’t afford to but also because I had a sense that I was going to be outsmarted, sold a pup.

Even after five years of collecting and reading, I knew at the age of fifteen that I was lost in a world of experts. I didn’t believe I would be deliberately cheated but that I would cheat myself; I would be offered a vast choice of Penny Reds from the 1860s, and I’d be bamboozled, and I’d flee the shop in a shaming panic. Of course, I had my Stanley Gibbons catalogue as guide, but that was too crude a compass to steer me through so many subtleties of shade and printings and plate numbers and postmark cancellations, all of which affected the price.

I needed a simpler approach, and before I got the tube back to Hampstead Garden Suburb I would visit the philatelic counter at the large post office in Trafalgar Square, where they understood and indulged a boy-collector’s needs and would sell you a whole sheet or particular sections of a sheet such as the ‘traffic light’ control strip down the side indicating that all the colours were present and aligned. In my teens I would buy new issues in blocks of four, for no particular reason other than they looked more solid than individual stamps. I write ‘no particular reason’ and now wonder about it, because perhaps there was a very particular reason: greed. Not desperate avarice (though of course this afflicts collectors as well), rather the ambition to put together an album more desirable than those of one’s peers and one which would increase in value over time. There are other convincing reasons to love stamps – an appreciation of their beauty, the thrill of the hunt, the pursuit of completion – but none is so compelling as the profit motive. It exists in every collector I have known. No matter how many people say otherwise, I won’t believe that any stamp collector over the age of seven does not have profit somewhere at the back of his mind.

4.

For about twenty-five years I forgot about stamps, or at least I neglected to collect them. First came university, then work, then marriage and children, a mortgage. Then, when I was in my early forties, my interest ignited again. I can’t pinpoint the cause – perhaps it was an article in the newspapers, or a browse online – but my enthusiasm returned and with it just enough disposable cash to pursue the stamps I could never afford in my childhood. What I wanted was, in a word, errors: the Post Office Tower stamp without the Post Office Tower on it, and much else besides.

When I was younger I could recite a list of the most famous errors better than I could recite ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’. I knew them still. For example:

1961 2 1/2d Post Office Savings stamp missing black and the 3d of the same set missing orange-brown

1961 European Postal Conference 2d missing orange and the 10d missing pale green

1962 National Productivity Year 3d and 1s 3d, both missing light blue

6d Paris Postal Conference Centenary missing green

3d 1963 Red Cross Centenary Congress missing red

These are British stamps that I can understand and, though rare enough, they are sometimes affordable. In the period that interests me – before Britain decimalized its currency (and its stamps) in 1971 – well over half of all issues had something glaringly wrong with them. Not the whole issue, of course, but a sheet here and there where the printing machine had run out of ink, or a paper fold had caused the colour to be printed on the gummed side. Even a schoolboy couldn’t make many mistakes with stamps like these, and even a person with no interest in stamps could see the appeal. Tens of millions printed and sold, all of them perfect – the perfection of the machine – and here and there a flaw, a beautiful accident, which had escaped the eyes of the inspectorate. Accordingly, stamps with errors will always be more sought after, and dramatically more expensive, than stamps that are perfect. This feature alone makes stamp collecting an exceptional and perverse hobby. No one wants a Picasso with missing bistre. A misshapen Ming vase? A 1930s Mercedes without headlights? There are some coins with errors, and some rare vinyl records with misprints on the labels, but they do not form the cornerstone of a collecting hobby, and they do not make men bankrupt. The first big error appeared on a stamp in 1852, an engraving slip that caused the word petimus to become patimus, thus changing the meaning of the inscription on the British Guiana 1 cent and 4 cent from ‘We seek’ to ‘We suffer’. Ever since, errors have been the most treasured items available, or rather, unavailable. The Swedish tre skilling banco yellow of 1857, the only known example that isn’t the intended green, was discovered by a fourteen-year-old schoolboy in 1885. It was sold at auction in 1996 for £l.4m – making it pound for pound the most expensive man-made object on earth.

I don’t think I mentioned the Post Office Tower error to my father in 1968. It cost several pounds. Several pounds for a stamp! You could send an elephant first-class for that. My father would have been intrigued by the idea that imperfection equalled added value but he would also have doubted it (a chipped glass or an unreliable wristwatch were just things to be endured until you could afford something better). How was he to know that there would never be more than thirty of such stamps? How could he have known that a stamp worth a few pounds in 1968 would be sold at auction in March 2005 for £1,300?

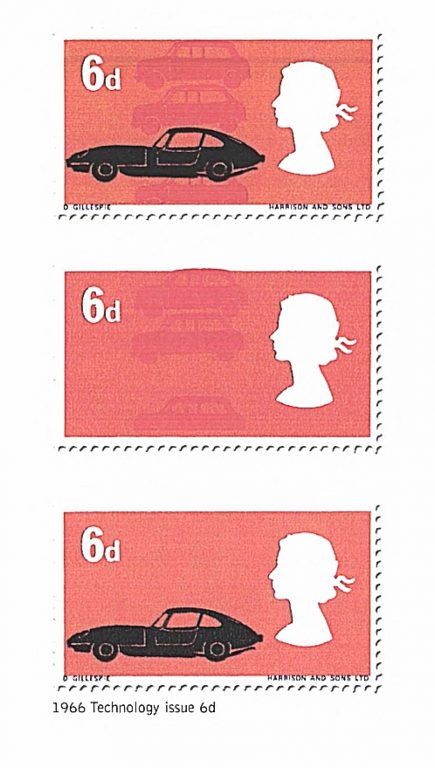

Studying these rare stamps in my schooldays I learned a bit about history and a bit about colour. I knew what bistre was, and agate, and could distinguish new blue from dull blue. But what I really learned about was inflation. The 1966 Technology 6d issue, for example, which should have contained three Minis and a Jaguar, but instead had only the Jaguar against a bright orange background, was on sale in 1967 at the Globe Stamp Co. in William IV Street, just off the Strand, for £95. A year later the price was £130. At that point the precise quantities of the error stamp were unknown but today it is thought that there are just eighteen mint copies. In an auction in March 2005, a collector bought one for £6,110. Of course I would have loved to have owned this stamp just as I would have loved to have owned all the others. But my favourite was five years older.

In 1961, the Seventh Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference was held in Westminster. There were two stamps issued. The 6d value was a horizontal rectangle with a purple background and a gold overlay depicting the roof-beams of Westminster Hall. The 1s 3d stamp was vertical, with a racing-green background, and was split into two halves: on the top was a picture of the Queen printed in dull blue, and beneath it was an engraving of the Palace of Westminster and a mace and sceptre. On the error, there was no Queen. Simple: a white box on a green stamp. In the late 1960s, when I first became aware of it, it was the most beautiful small object I had ever seen, and remains so for me today.

In 2003 it took me a while to tell anyone of my revived passion for stamps. When I eventually disclosed it to my family, my children spoke the same word they use to describe anyone over the age of twenty-five who wears trainers and affects an interest in rap: ‘Sad.’ My wife took a tolerant interest (in the same way I show interest in her passion for the theatre), though now her questions are invariably focussed on one aspect of it all. I want her to say, Tell me about the history, the beauty, the rarity! Tell me about that one!’ but mostly she says, ‘How much was it?’ And so while I, an adult with money, returned to the Strand confidently, I was at the same time more furtive than I’d been as an adolescent.

Sign in to Granta.com.