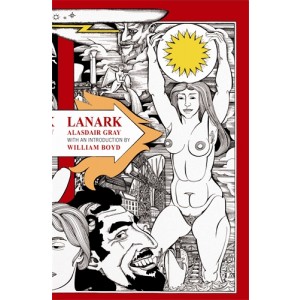

In 1983, I had just left school and moved from our Lanarkshire council estate to a Glasgow flat with the idea of dancing and writing. My neighbour was a poet and he introduced me to his friend, Alasdair Gray. Gray’s living room had a stack of paperback copies of Lanark in it – his first novel, which had come out a couple years earlier, in 1981. I hadn’t met a novelist before, so when he gave me a copy, with a funny inscription mentioning my friend and wishing me the best ‘for my future in the theatre and elsewhere’, I carried it around with me everywhere. I read in corners while I was waiting to be called on set as a television extra, backstage in pubs while waiting to dance, at home waiting for my agent to ring.

With Lanark, I found what I had been waiting for in my reading life. The jumbled structure – the book is in four books and begins with book three – mirrored my teenage experience. Thaw the artist struggling to find his way, Lanark his alter ego, and Unthank and Glasgow with their dystopian disintegration spoke of the personal and the political as inextricable. The notes with fake and real plagiarised sources showed how international citations might be true of something local and familiar and how context could indeed be everything.

The personal, immediately relatable story of the fall of a man (Thaw) was mirrored by a society’s collapse. Both structure and content had a symbiosis that made Lanark three dimensional, vivid, absolutely affecting because it spoke of what was around me. This book had power, not just to help me escape from the boredom of waiting, but to change the way I viewed my own actuality. Oft accepted imitations and conventions might be ignored, altered and defied, yet somehow a voice might be all the more audible because of it.

For the first time I felt included. It seemed that a literary novel could be about the world that I lived in too.