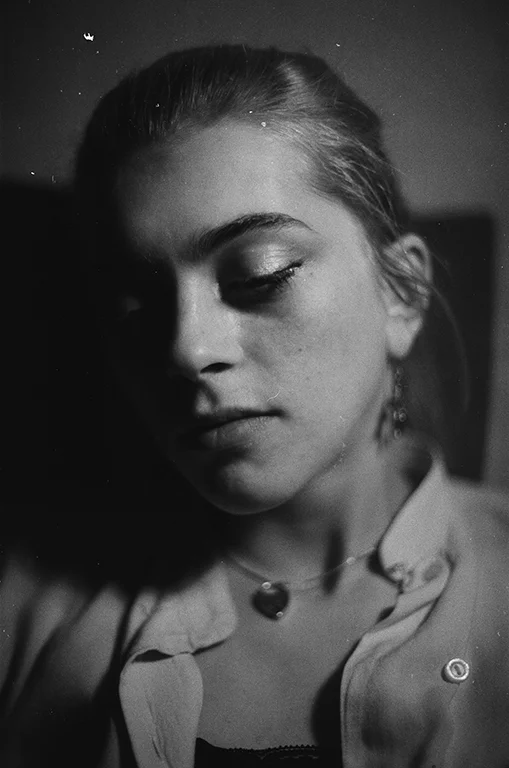

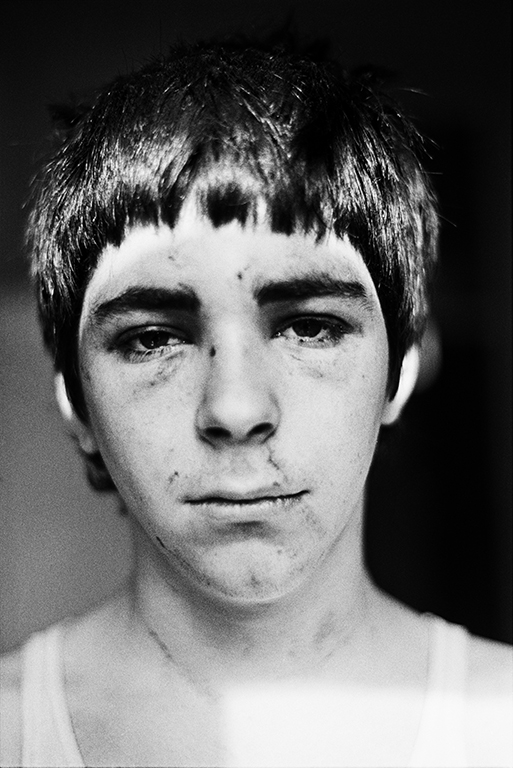

In his calling-card self-portrait, Smiler isn’t smiling. With good reason; he has been assaulted, traditional British street violence under the protective rubric of festering resentment, ugly politics. National Front collision, 1980. Full face, front on, abraded. Presented as evidence. His friends and associates, fellow travellers in the art-squat-music, just-do-it community, testify to his charm, his affability. ‘Charismatic and beautiful,’ wrote Tim Banks.

Smiler was on the scene with his weaponised camera, but he came from another planet: Nairobi. He has an older identity, shaken off by his submerged London life. His passport says: Mark Cawson.

Cawson’s mother arrived here in 1939 on Kindertransport and was adopted by an English family. Her parents had been killed in Riga death camps. Cawson’s father worked with both Maasai and settlers, until he was washed off a bridge, drowned. The wild colonial boy is dumped, well before he has acquired his alias, at a Nigerian boarding school. ‘When Smiler’s stepfather went to visit him, he could not understand a word Smiler said,’ notes Neal Brown in Smiler, a telegrammatic book published by Sorika in conjunction with the photographer’s only mainstream exhibition, at the ICA. And then, on achieving his majority, a stroke of fortune, the young man, exiled in a shifting and shiftless community, inherits £2,000. He buys camera equipment. He lends Keith Allen £500.

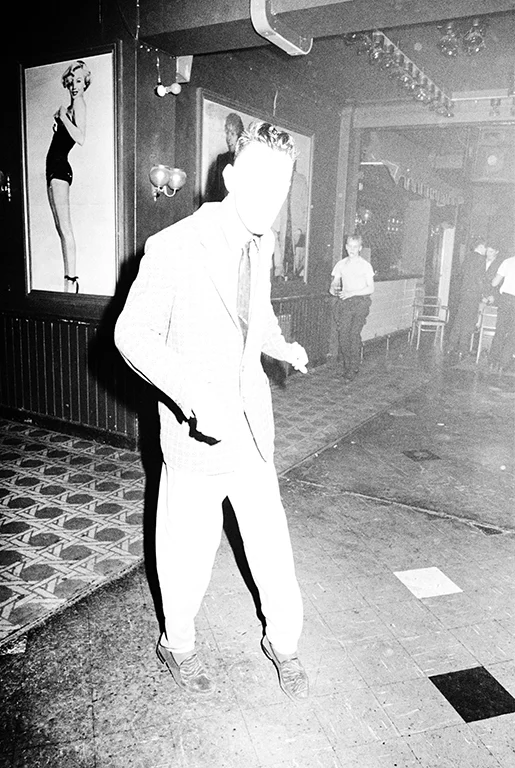

Smiler is a spectre from a subcultural milieu. His outline feels as opaque and enigmatic as David Bowie – anaesthetised in cocaine reverie, finding himself two miles out of a nowhere town in Nicolas Roeg’s film of the Walter Tevis novel, The Man Who Fell to Earth. ‘Human, but not properly, a man.’ A shivering spook with special interest in future-world camera technologies, privileged ways of seeing. Smiler, like Bowie, has come to ground: a forced landing in an airless environment in which he sustains himself by making fallible records on photographic paper. Records that threaten to melt the page if we don’t imprint them on our consciousness. The image journal is time travel.

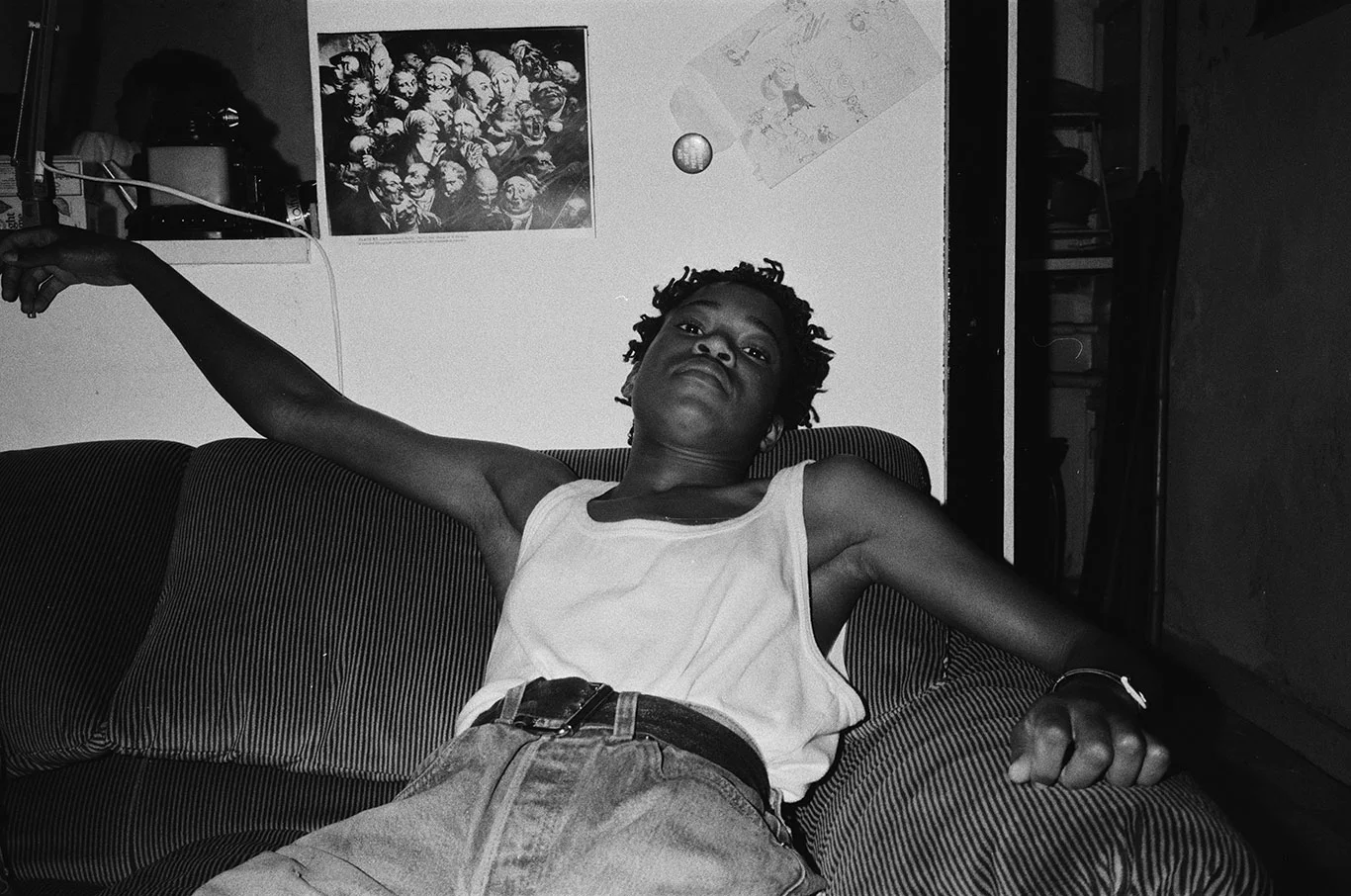

Smiler’s catalogue of the lunar faces of his cohorts in the countercultural squatting nexus is pure romance. Wrist-snap documentation becomes essential poetry. Images as natural as sneezing. And as plosive. Solitary dancers cakewalking in a night-world are scorched in atomic aftershock. They are like casualties collected from hard-news crime scenes by Weegee and his dustbin-lid flash. These are the junk-jolted undead, reanimated by Smiler’s predatory and pitiless gaze. By being noticed. Surveyed before surveillance was universal. Before all-seeing conceptual snoop systems became the art of the state, where everything is captured in present time but nothing matters. The patina of excitement in Smiler’s portraits of dead friends, of drug parties like wakes, comes from our sentimental attachment to a past that never was, but which is vividly here when resurrected and reforgotten. Cawson’s prints are bleak Xeroxes referencing generations of resistance and addiction; from the punk orphans of Thatcher to disaffected Class Warriors; from the bohemian colonists of Notting Hill to sit-in polytechnic radicals; to second- and third-generation Situationists chasing a viable thesis. And all those dressed up and drifting particles looking for shortcuts to a good time.

Smiler hibernates. He has no interest in the long game, the blind faith of the courageous (or demented) outsider, hoping to be elevated from cult status to post-mortem name-check inflation. The bits of a past he is prepared to confess emerge when he lets rip, drink taken, on a late-night Tube ride. A strung-out barefoot walk in the early hours across a carpet of broken glass. The essence of squat occupancy is that it’s finite, performative: nicknames but no surnames. ‘Spotty Pete, Lulworth House’. No identity papers are required in King’s Cross, Camden Town or Latimer Road. In Smiler’s confrontational images, the dead outnumber the living. The salvaged account presented for future historians is Homeric. Eros and Thanatos. Named casualties. And opportunistic fucks. Survivalist routines with heroin punctuation in borrowed or invaded terrain. Demigods ascend or descend, playing their part in the comedy of squatocracy.

The pre-famous and the doomed children of television character actors cohabit, sharing their goods and affections. Smiler is in the room. He responds. Makes portraits. The visitant from another planet is finessing an autobiography of fragments. What he sees is who he is. A ‘no future’ aesthetic enhances the potential of the trigger instant: this print is awkward but it is all you are going to get. The ‘decisive moment’ of Cartier-Bresson, when chaos behaves itself, with all aspects in unique alignment, solicits admiration. Smiler, on the other hand, anticipates a coming world where compulsory pocket devices will do the heavy lifting. And every image cast against boredom carries consequence. He labours to keep his captures raw. The subjects are not consumers for anything freighted from a warehouse. They do their own shopping.

It can’t be claimed that Smiler achieved a Hogarthian critique of the society in which he lodged. Putative artists here, dismissed by a smashed Barry Flanagan in their Hornsey assessment, are beating their shaven heads against concrete columns. Brutalist blocks designed as indestructible monuments to social blight are laughingly called ‘House’. Smiler validates that privileged interval between ‘considerate’ construction and pitiless demolition. From a high window he notices a fire nobody can be bothered to put out on the wrong side of the tracks. Firemen watch. Location scouts evaluate the potential for screen time, documentary or cop show? The broken teeth of that other London, CGI towers and investment silos, nibbling at a misted horizon. If the photographic seizure works, and appeases reality, you are transported, directly, to this other set.

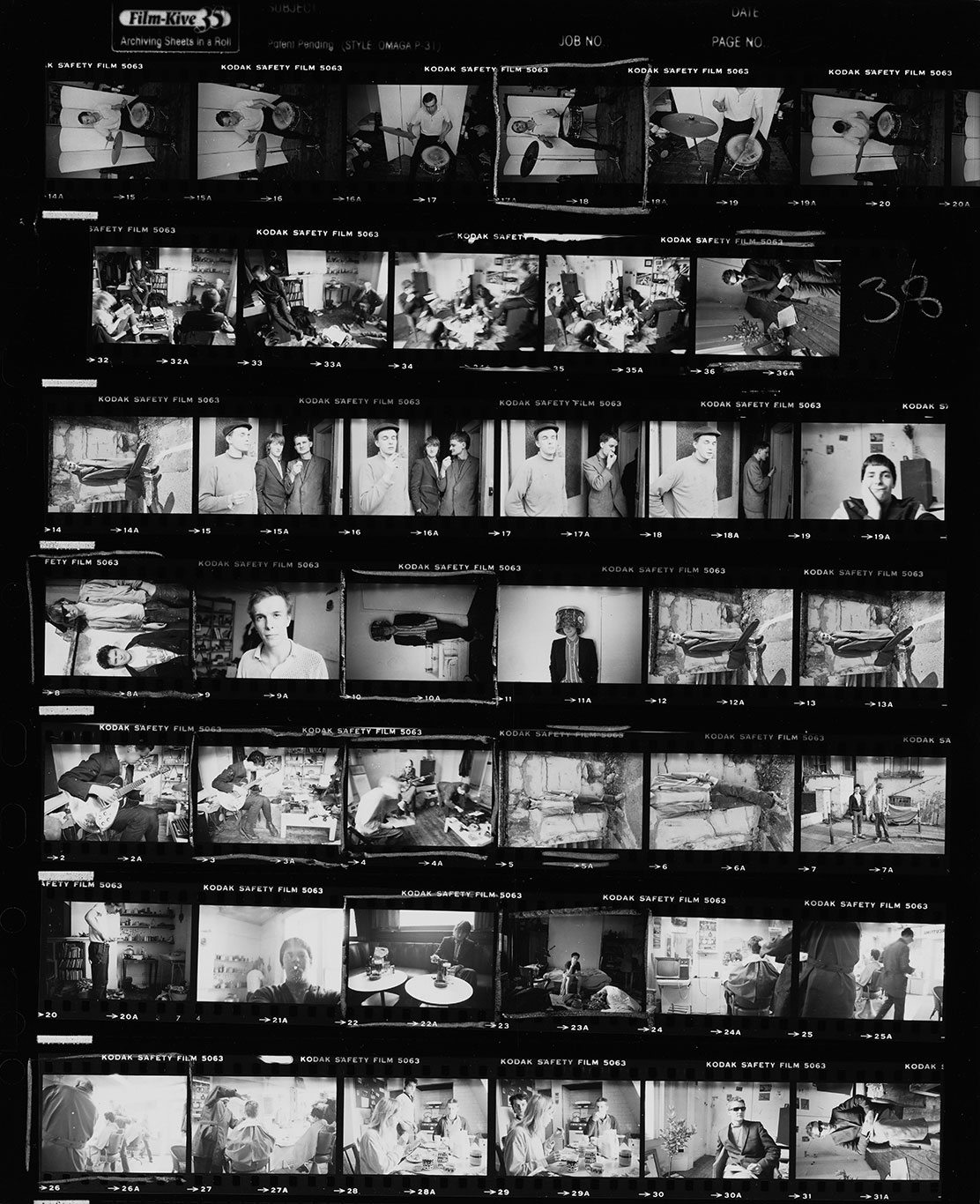

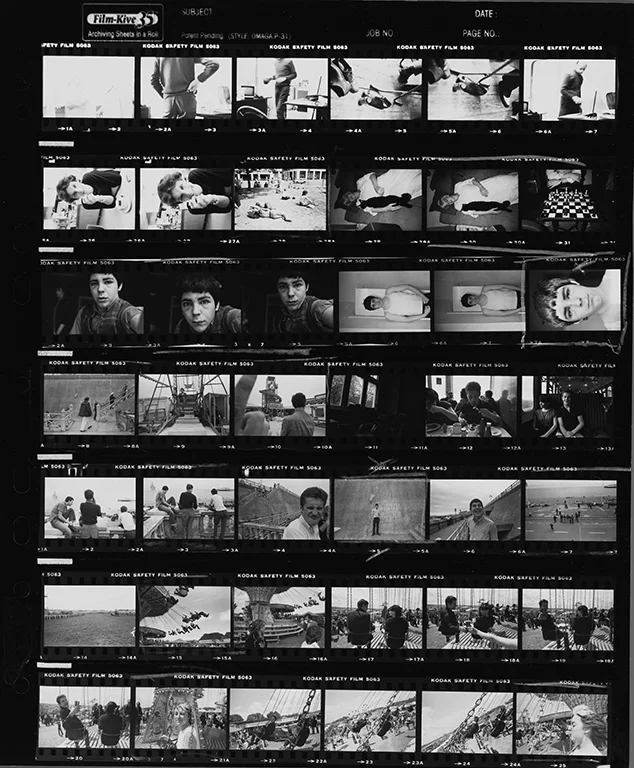

Cawson has left a record that cannot now be challenged. His considerable and largely unseen archive accurately represents its own history. The prints look disposable, casually framed, throwaway. They flirt with happenstance. Action before theory. If we take them seriously, as indeed we should, they challenge the necrophile calculation of Warhol’s Polaroids, the silk-screened multiples for investors. Smiler’s photographs are like the heroin-chic versions that dressed style magazines of the period. But they have the integrity of accident, managed carelessness. They could survive without the witness of the artist responsible. The figures Smiler opts to depict quiver on the cusp of refusal: their eyes register affront, suspicion, weary tolerance. To be exhibited is to acknowledge mortality. This moment will become all moments. Brown recollects walking across a park – ‘twilight, plants and animals’ – towards ‘a recovery gathering’. Smiler has entrusted some of his archive to his friend. Then he decides that he wants one particular print back. But Brown says that he never had it. Smiler ‘was giving archives to me and others in quiet anticipation of his death’. The images we are permitted to access here, by way of Cawson’s son Louis, have a defining quality: resistance. The survival of these negatives, beyond the evidence of those lost lives, is miraculous. Preconceptions around the vulnerability of the strictly limited selection of images chosen for an exhibition are challenged when we inspect the untapped potential of a rescued contact sheet. Now a fuller, rounder version of Cawson’s autobiography emerges: he lives again.

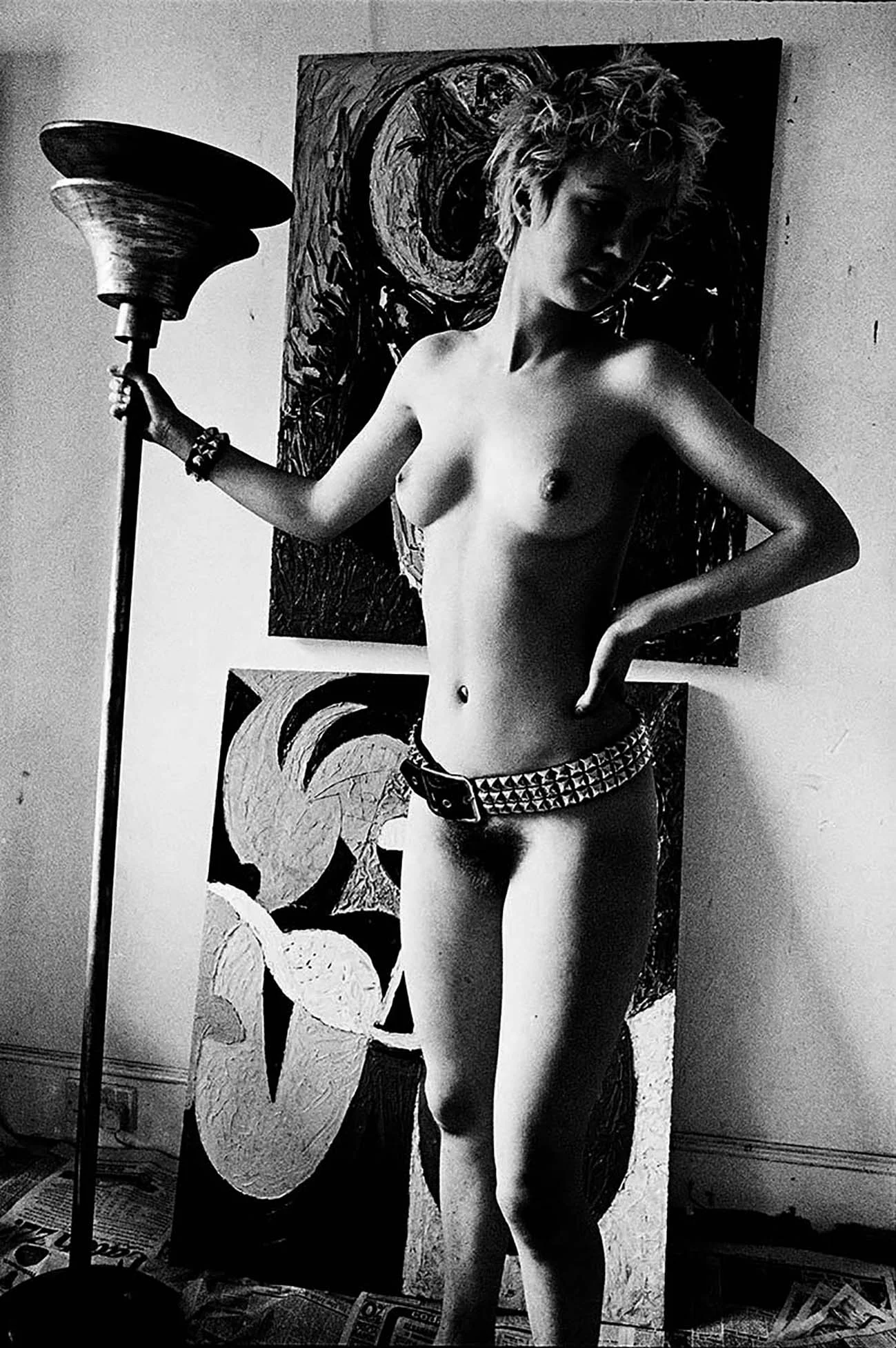

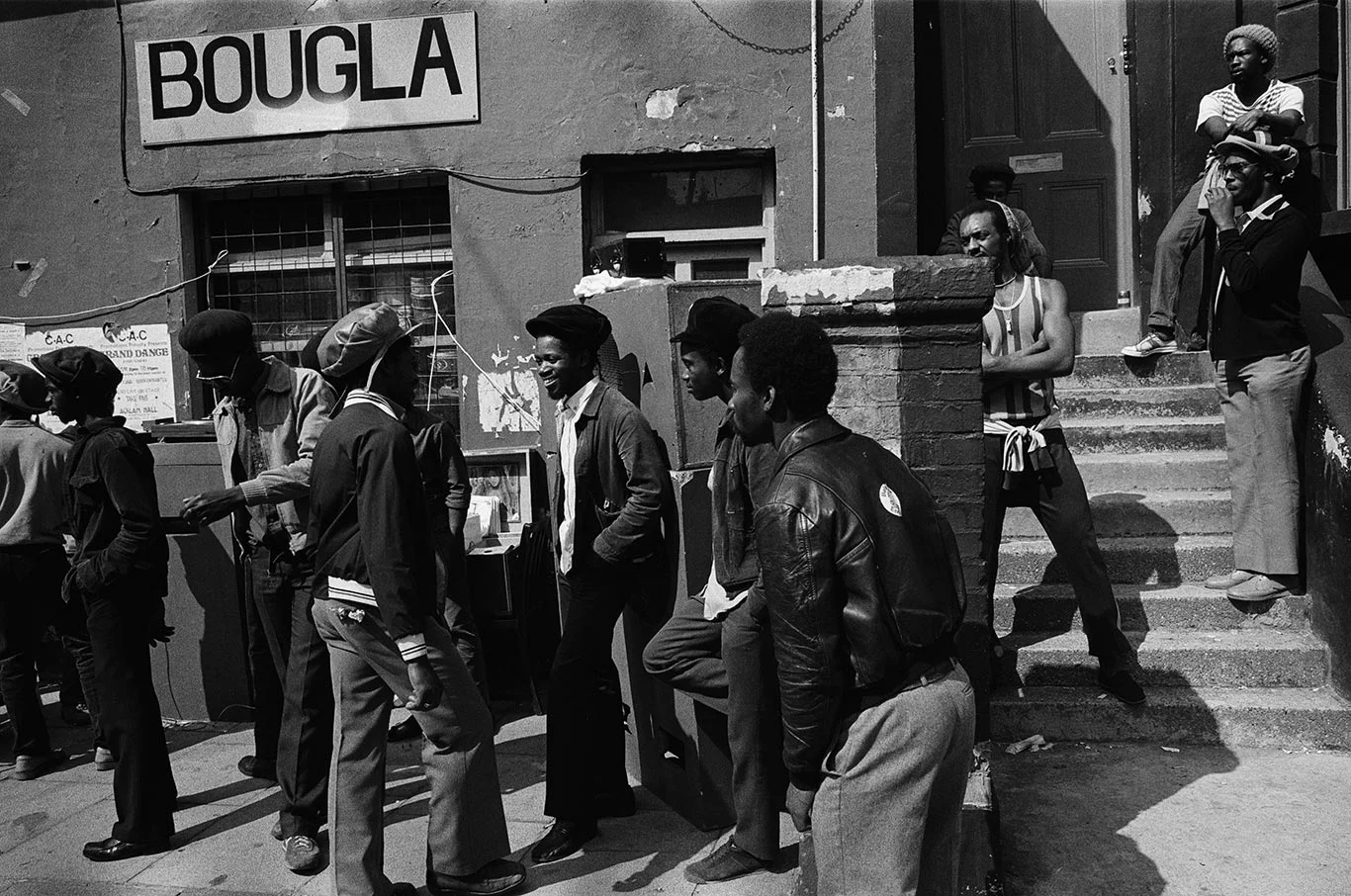

There are alternative choices beyond the nakedness of that self-portrait after the assault. There are excursions to the seaside, remembered pleasures. Associates relax over tea and ciggies in greasy spoons. They smile! Young Black men gather on the streets of Notting Hill. And there is a prophetic long shot, pulling back from the intimacy of the portraits, the nudes, the haircuts. It offers a Ballardian vision of the Westway as a discontinued future. The elevated highway is flanked by a twenty-storey tower block, fresh from the 1970s. Its long shadow falls across the estates, the curve of railway, and the coming spread of incontinent development with its terrible consequences.

The prints from which Smiler’s integrity must be tested belong to a limited number of specific London locations at a specific period. In a very smart move, the photographer asked for the emphasis on the commissioned text for Smiler to be placed on Brown rather than himself; thereby assuring his mythic status as a Harry Lime ghost in his own novel. He landed Brown with the task of listing the lost, libelling those who deserve it, while giving up addresses of relevant squats, fast-food pits, clubs and addiction parties.

Property and possession: the continuing shame of London. Back in the sixties, strategies were imported from Provos in Amsterdam. Warehouses were found in anarchist alleys. The sleeping-bagged floors of Whitechapel were like performance tributes to Jack London’s photographs from The People of the Abyss. There were meetings in Stoke Newington and Shoreditch, addressed by European activists, and attended by locals, bruised in physical battles to maintain occupied terraces in Redbridge. Loose associations of like-minded drifters invaded council-owned properties left empty, while they waited to become under-resourced tower blocks. There is a long and complex history, beyond the scope of Smiler’s portfolio. He worked at one remove, highlighting the quotidian. A predicated overdose with high heels and empty file boxes in King’s Cross. A figure, head in a bag, reversed balaclava, bonelessly slumped like a political prisoner forced to stand against a wall. And described as ‘Psychosis, All Saints Road’. Temporary occupants, warming the stones for grand development projects still in the pipeline, are under notice. The surrounding microclimate, also registered by Smiler, features the terminal dread of waiting for service at a McDonald’s franchise in Kensington. Along with a suited and muted celebration of Jehovah’s Witnesses at a wedding in Monmouth Road. Hard to tell if ‘Spotty Pete’ of Camden, with his flowered shirt and parrot tattoo, is lockjaw-yawning or deceased. A naked, smoking Jane holds – as instructed? – a print of a young Sophia Loren over her face. Seamus, on the sixteenth floor of a squat in Shepherd’s Bush, is embedded in the scattered ephemera of possession: a hulking safe-sized Dansette, floor-mattress with tartan rug, ties and belts dangling from a waterpipe. Whitewashed prison bricks and barred window. The harsh reportage offset by painterly light dignifying the sitter: fine eyebrows, moustache, dimpled chin. And provisional acceptance of fate’s cruel hand.

End notes in Smiler: eleven friends dead. AIDS cull. Overdose. Self-harm. ‘Property prices go up. Squatting criminalised . . . Joy upon joy of intensity of love. Drinking lots of water . . . Smiler doing new work.’

The revealed alignments of small interconnected groups in unwanted properties under permanent threat. Possession of self-medicating pick-me-ups persecuted. Dispossession a fact. Smiler’s portrait after the NF beating, two or three stages beyond what is comfortable to see and know, recalls Étienne Carjat’s famous photograph of the runaway outlaw Arthur Rimbaud, who also had his subterranean London period. ‘Right now, I’m damned. My country appals me. The best course of action: drink myself comatose and sleep it off on the beach.’

Aidan Andrew Dun starts to write, after ‘seven or eight years of study and research’, Vale Royal, a poem of place. He tells us that he looks up from his copy of Rimbaud, over the unresolved and ultra-urban particulars of King’s Cross: railway, canal, burial ground. It is 1973. He nests in a squatted building. Uncollected by Smiler, Dun was one of those who disinterred local mythology and made it universal: the ground plan for Blake’s Jerusalem. Rimbaud, a trans-dimensional neighbour from Royal College Street, risked the only possible escape. He gave up poetry, went into colonial trade, and became his own portraitist, with a remotely triggered selfie on a coffee plantation in Harar in 1883.