In contrast to virtually every other European country, the Soviet Union has been notable for its determination to give women a place in society equal to men’s. The extent of the commitment is evident in the details of ordinary Soviet life. It is taken for granted, for instance, that all women should be educated and that they should be encouraged to take up a profession – fifty-one and a half percent of the Soviet labour force is made up of women – and women, like all Soviet citizens, are guaranteed employment. Moreover, the familiar images of women as sex objects are rarely seen in film or pornography or advertising: female sexuality is free from so many of the exploitative commercial practices evident in the west.

But while it is true that women form a crucial part of the work force, it is difficult to see them as being independent and equal in other aspects of society. Lenin is reported to have replied to the request to write about sexual and family education by saying, ‘Further ahead – not yet! Now all my strength and time have to go into other issues. There are greater, more serious problems.’ And Marx and Engels have been understood as believing that true liberation of women would only be possible with the abolition of personal property, allowing women to ‘regain’ the equality they originally possessed. But now, with private property abolished, with some of the more urgent economic needs met, what kind of liberation has actually taken place? Why, after such inspired beginnings, has this liberation appeared to have slowed down? And just how compatible are feminism and socialism? These are among the questions that Carola Hansson and Karin Lidén address. Both have done a great deal of research in Soviet life and Granta publishes here some of their work, consisting of four fairly developed interviews, a number of rather startling statistics, and a brief selection of the highlights of some of the other interviews. All the interviews were conducted in the women’s homes, in Russian, without an interpreter. There were no authorities involved and the women’s names are pseudonyms. The tapes were left in Moscow once the interviews were completed, and, through secret channels, were passed on to Stockholm, arriving six months later.

Liza

We first meet Liza in her brother’s home. She is wearing a long red robe with a deep décolletage, has blonde curly hair, wears black mascara. Her eyelids are pale blue and her lips a dark rose.

I’m twenty-eight. I have a degree in literature and work for a publisher. I have a son, Emil. I had a husband, who was an artist, but now he’s gone. We got married in 1970 and divorced in 1975.

Does your former husband spend time with Emil?

No, he rarely sees his father. The situation is complicated. When the baby was born I gave him my surname. I decided that since I had had to carry the whole burden and I suffered the most, I wanted to give him my name. His father was very upset that the boy didn’t have his name, and now they almost never see each other. Emil never gets anything from him.

You were born in Moscow?

Yes. Six of us lived in a room twenty square metres in size, which was part of a communal apartment. It was Mama’s room. Papa wasn’t born in Moscow and when he married my mother they settled down in that room. There was also Mama’s sister, Grandmother, and I, and then my brother, Alyosha, was born. In 1937 Mama’s father was put in prison. If my grandmother had divorced him she could have avoided going with him and could have stayed with her three children. But she didn’t think it was right to divorce him after he was jailed, so she went to prison for eight years as a family member of an enemy of the people. When the children were left alone they were forced to leave their apartment, even though her husband had had an important position in the government. They were kicked out, and my mother, who was sixteen at the time, was left with two small children, eventually settling into the very same room where I grew up.

How do you remember your childhood?

I think I had a very happy childhood, so happy that . . . Marina Tsvetayeva writes that her childhood was so happy that when she reached sixteen she wanted to die. We did live under difficult circumstances. Papa was a poet and a writer, and used to block himself off in a corner to work, which gave the room a cramped look; he wrote some of his most important works right there in that corner. It was a terrible life, and still Papa kept on writing . . . We had nothing. When I was born they had only potatoes on the table to celebrate my birth. They didn’t have the money for a baby carriage, so they put me in a basket that Papa hung outside the window and that boys would sometimes throw stones at, thinking it was fruit or something. On the whole I remember my childhood as very happy – especially my relationship with my father.

Do you think that women and men have the same goals in life?

Yes, but I think that women are more honest than men. For example, in the thirties, when the whole country was a mass of lies and betrayals, the women lied less. Akhmatova and Tsvetayeva were only ‘fragile creatures’, but they didn’t lie. They could be broke, they could starve – Tsvetayeva went so far as to hang herself – but they didn’t lie.

When we were forbidden to believe in God, the soldiers came to the villages brandishing their pistols, asking, ‘Are you believers?’ ‘No,’ everyone answered. But still the women went to church, and it’s they who have kept religion alive.

Would you have chosen another profession if you had been a man?

I don’t know. Had I been a man I would have travelled around Russia, and also would have been able to change jobs often. As a woman, that’s hard to do.

Are there typically female professions in Russia?

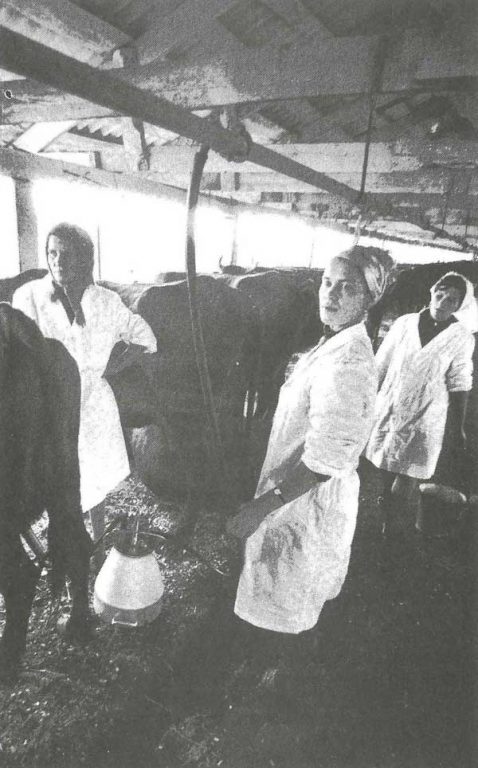

Of course. Textile workers, for instance, are mostly women. Doctors and physiotherapists are also mostly women. Almost all teachers are women. At day-care centres practically all employees are women. People who clean are usually women. As a matter of fact, most service work is done by women, at home and in the community. In the country women work mostly on the kolkhoz. 1

Why do you think that’s so?

Because the salaries are low. It’s terribly sad. Our women have a horrible time and of course prestige also plays a part. A man won’t do household or household-related chores. Here, dishwashers are always women. Teachers are also very badly paid, and that’s why they’re mostly women. Women aren’t readily accepted in important posts.

Could you imagine a man working at a day-care centre?

Yes, I can imagine it, but one doesn’t often find men suitable for that. Here there are very few responsible fathers; they all drink too much.

To change the subject to sexuality. Do you have contraceptives in the Soviet Union?

We have the IUD, although it isn’t used very much. Women who want one have to queue for a long time. We try not to use the pill because of the possible danger to a future foetus. Some also use aspirin, but that’s also considered to be dangerous.

But above all we have many abortions. They’re horrible, absolutely horrible. But what’s the answer? Our contraceptives aren’t any good. There are condoms, but they’re so repulsive and bad that we would rather go through an abortion . . . The first Christians copulated only in order to procreate. In my opinion abortions are punishments for our sins.

Have you ever had an abortion?

Yes, many – seven. It’s hard both physically and psychologically. Now that it’s done with drugs there’s no pain, but it’s hard on the psyche.

How did you react when you discovered that you were pregnant the first time?

I was hysterical. It was totally unexpected, since I didn’t believe . . . I couldn’t imagine that children were conceived that quickly. No one had told me anything. We don’t learn anything about sex in school, and no one in the family talks about it. I got together with my husband, and I got pregnant immediately. It was so strange that I had an abortion. I went through with the second pregnancy but the delivery was very difficult. I begged for a Caesarean, howled like an animal, screamed so much that they finally had to give me something to induce labour, and I had terrible contractions and kept on screaming until there was blood in my mouth. My baby was born in a special clinic, but still . . . During the delivery I was badly torn, and they didn’t even sew me up.

As a woman, what do you find the most difficult problems to cope with?

My main problem is that the man I love is married and has a child. Sometimes when things are most difficult I long for the presence of a man who is strong, a bogatyr2 . . . who would shelter me so that I wouldn’t have to think about anything.

What, according to you, are women’s most pressing problems here?

Their husbands’ low salaries, and the limited time they have left for their children. Most women aren’t wildly enthusiastic about their work; they’d like to bring up their children in a normal way, but they’re too busy trying to make money. It seems to me that our women suffer from equality.

What do you mean by equality?

Here equality consists of the women carrying the heaviest burden. Here a woman’s life just fades away without her being aware of it. She’s young, then suddenly she’s old, and she’s buried without knowing why she ever lived.

Are you familiar with the women’s movement in the West?

Yes, I’m familiar with the movement to legalize abortion, and women’s rights, but where the right to vote is concerned…here all women have the right to vote. We don’t need a women’s movement. Here we’re all convinced that everything is the way it ought to be. But I think when women were emancipated, it actually amounted to man’s liberation from the family.

Is there anything you wish to add?

Yes – it’s terrifying when a woman speaks. The truth comes out, and a very real pain emerges.

Sign in to Granta.com.