When Granta asked Renata Adler about contributing to this issue, she off-handedly mentioned an unpublished piece she had been commissioned to write years before by the New York Times on the occasion of the death of her friend, Hannah Arendt. The article was a 6,000-word memorial that included a detailed appreciation of Arendt’s oeuvre. Adler, however, shelved the piece after writing it. ‘I thought she would have hated it,’ Adler told Granta. After retrieving the article from her archive this past autumn, Adler looked at it with different eyes. ‘If anything,’ she said, ‘it’s too distant.’

The piece is not only a forthright reckoning with Arendt by a writer from a younger generation with a shared German émigré background, but also marks the points of contact and contrast between the two writers (though Adler refuses to be compared with Arendt). Adler first met Arendt in 1963, shortly after Arendt’s two-part report on the trial of the SS commander, and high-level organizer of the mass slaughter of European Jewry, Adolf Eichmann, appeared in the New Yorker. The Eichmann articles were not only controversial for coining the phrase ‘the banality of evil’, but also for calling attention to the leaders of the Jewish councils in Europe who, according to Arendt, had to a certain extent cooperated with Nazi directives. Adler’s unpublished piece is concerned in particular with Arendt’s understanding of politics, and her moral understanding of the responsible way to be in the world. For Arendt, neither friendship, nor even the individual self, can exist without making reference to the public realm. In this sense for Arendt, as Adler writes, conversation does not merely sustain the world, ‘it is the world.’

Readers can view the original, unedited version of Adler’s essay here. What follows is a supplementary conversation, in which Adler relates some of her memory of Arendt.

Renata Adler was born in 1937 in Milan, the daughter of German Jewish parents who left Nazi Germany in 1933. In 1939 they settled in the United States. Adler grew up in Danbury, Connecticut, and in 1962 became a staff writer at the New Yorker under William Shawn. She is the author of the novels Speedboat and Pitch Dark. Her works of reportage include Reckless Disregard: Westmoreland v. CBS et al., Sharon v. Time and Irreparable Harm: The U.S. Supreme Court and the Decision that Made George W. Bush President. Her essays have been collected in Toward a Radical Middle, Canaries in the Mineshaft, and most recently in After the Tall Timber.

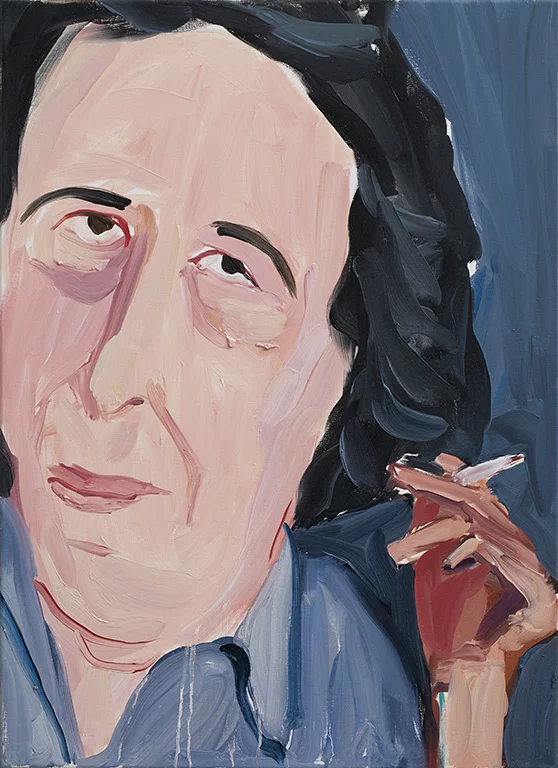

Hannah Arendt, 2014 Chantal Joffe, Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro

Editor:

How did you first come into contact with Hannah Arendt?

Renata Adler:

I was fairly new at the New Yorker. In fact, I was very new at the New Yorker. The pieces on Eichmann’s trial had just come out in the magazine.

Editor:

This was the two-part report Arendt wrote from the trial in Jerusalem where the SS commander Adolf Eichmann was tried, convicted, and executed by the young Israeli state for his work in facilitating and coordinating the mass slaughter of Jews and others under Hitler.

Adler:

That’s right. I ran upstairs to Mr Shawn’s office, and I said, look, I think – I know this sounds peculiar, but I think the magazine needs to run another piece, very quickly, whether by Miss Arendt or by somebody else, but preferably by Miss Arendt, which explains what the Eichmann pieces really say.

Editor:

This is 1963, and you were twenty-five years old. Why did you think the articles required additional clarification?

Adler:

She stressed collaboration between Jewish leaders and the Nazis to the point that I just thought it’s going to be highly offensive, and also perhaps misleading in a way.

Editor:

They did offend a lot of people. Irving Howe wrote that Eichmann in Jerusalem ‘provoked divisions that would never be entirely healed’ in the Jewish New York intellectual world.

Adler:

I thought the pieces might be misunderstood.

Editor:

Did you disagree about the substance of them?

Adler:

No, I trusted her completely.

Editor:

Then what was wrong with them?

Adler:

There was perhaps an element of snobbery to them, which I think she never was quite aware of. An edge of contempt. I loved her dearly, I admired her enormously. But I think the ‘banality of evil’ – although I can understand why she used the phrase – it isn’t right. It isn’t right. ‘Banality’ is a strange word to use. It’s an intellectually strange word to use, no? It really trivializes something. There could have been another way to express it, I’m sure.

Editor:

Even if ‘banality’ is pejorative, it might have had a different inflection in her ears, no? It was a word that she would have learned in a German gymnasium. The ‘Banausos’ – from which ‘banality’ derives – were the manual laborers of Ancient Greece. Couldn’t it have had a more clinical meaning for her?

Adler:

But it’s trivializing and dismissive in English. In the way people used to use the word ‘middle class’. But I think I can understand why she used it. Because she was also writing against the glamorization of evil. There’s a long history of romanticizing evil. No matter whose devil it is, no matter where evil is depicted: there’s something quite elegant about it. You don’t get a devil who’s a pudgy fat boy. So in another way Hannah’s choice of words is exactly right. Exactly what she wanted to do was deglamorize evil. Even now, even again, the devil is not a glamorous character. It’s not something with a wonderful tail.

Editor:

But William Shawn didn’t think it was necessary to run a defense of Arendt at the time in the New Yorker, so then what happened?

Adler:

Sometime later, when the book Eichmann in Jerusalem was published, Mr Shawn appeared in the doorway of my office. He said that Miss Arendt would not mind if I were to write a letter to the New York Times. The letter, which he himself would edit, would be a response to the awful review by Michael Musmanno, who had been a judge at Nuremberg. [Ed. Musmanno’s review appeared on 19 May 1963, and argued that Arendt’s book read like a defense of Eichmann against the Israeli prosecution.] The Times did not run my letter. Then Mr Shawn appeared in the doorway of my office again, and he said that Miss Arendt would not mind, if I would agree to it, for him to run my letter as a Notes and Comment in the New Yorker. He did run it. Mr Shawn appeared in my office again. He had this way of appearing in the doorway of one’s office. He said Miss Arendt would like to invite me to tea.

Editor:

What were your first meetings with her like?

Adler:

I thought of her more as a sort of parental figure in the beginning. There was scolding. When I went to the New York Times to become the movie reviewer, she said, ‘When are you going to get serious?’

Editor:

Did she give you a sense of what she thought of your writing?

Adler:

That’s the funny thing about this note on this scrap of paper I recently found, which she had sent me. She says she likes a story I’ve written.

Editor:

What story?

Adler:

I don’t really remember. I’m still so embarrassed by it that I’ve never looked at it again.

Editor:

How can you be embarrassed about it, but not know what it is?

Adler:

I just remember the embarrassment!

Editor:

Didn’t Arendt take film seriously as an art form?

Adler:

I think not. She would have thought about my writing about it as selling out. But then so did my brother. So did Hannah’s husband Heinrich Blücher. So did Harold Rosenberg.

Editor:

Your novels Speedboat and Pitch Dark appeared after Arendt died, but did you ever discuss your fiction?

Adler:

It did come up, but I don’t remember how. She had a literary side. There’s that wonderful sentence about her friend Randall Jarrell.

Editor:

The one about ‘the precision of his laughter’?

Adler:

‘The precision of his laughter’! I mean, ‘the precision of his laughter’. Who else could say that? She was capable of phrases like that. So when it gets reported that Mr Shawn didn’t like Hannah’s writing because her prose was turgid, I think: You can’t even say that. It just isn’t true. I mean, ‘The precision of his laughter’!

Editor:

You’ve pointed to how Arendt achieves a special kind of authority in her prose. And you’ve also respectfully pointed to how this authority in her writing, alongside a drive toward fundamental concerns, comes with certain costs. The authority, you suggest, can sometimes crowd out precisely the kind of dialogue she aims to build with her readers. What’s your own feeling about authority in your own writing?

Adler:

I don’t think in terms of authority. When I think about prose I think about Evelyn Waugh and Muriel Spark, that kind of crisp style. Of course I don’t write anything like that, except that I sort of try to in fiction. What’s a good sentence? That kind of crisp . . . something. Hannah writes in such a different way. So, no, I don’t feel the authority thing, and now that you mention it, I wonder if Hannah did.

Editor:

This crispness you pursue on the page – what is it exactly?

Adler:

One thing it is, much to my astonishment, is monosyllables. I like sentences to end on the monosyllable. Or I really just tremendously like monosyllables. That’s not a Hannah Arendt thing. But that’s only in fiction. I don’t really seem to do that in non-fiction, where the sentences are sometimes longer than I remember. But I do care about the word. Some writers do, and some writers don’t. Some writers care about momentum or rhythm, but I think I’m very aware, maybe too aware, of every single word, although I bet an awful lot go by, because of course you can’t be aware of every single word. Hannah was also aware of every single word, but in quite a different way. She didn’t attach as much importance to cadence or rhythm.

Hannah Arendt, Passport Photo (sheet of four). 1933. Courtesy of the Hannah Arendt Bluecher Literary Trust / Art Resource NY

2

Editor:

You were both émigrés from Germany, albeit from different generations. Was that part of the bond?

Adler:

We must have spoken German in the beginning. Hannah would invite me to New Year’s Eve, to a party for refugees. Fellow refugees who were friends of Hannah’s. Some of them were quite old or seemed old to me. Of course, I went.

At the time I had a superstition, which was that I needed to be in bed, and perhaps asleep, well before midnight on New Year’s Eve. I don’t know why I had that. I can’t think of another one that I had like that. So I would go to these parties, and there would be these refugees – a generation older than I, at least. Then I would leave, saying I had to be in bed. And I thought, they all don’t believe me. They think I have something better to do, right? Some possibly, I don’t know, romantic, illicit thing to do. What else would they think? On the other hand, why would you go to a party of refugees at Hannah’s apartment on Riverside Drive if you had something better to do? It was very odd.

I remember a conversation on another evening, I guess where there must have been other refugees – one of them turned to me and said, ‘Renata, I didn’t know you understood German.’ And Hannah said, ‘Yes, the pity of it is that she used to speak it.’ Now, what was peculiar to me about that conversation is we’d been speaking German at all of the parties. They weren’t predominantly in English at all. So it just meant my German was declining.

Editor:

What were the parties like?

Adler:

Intellectuals, necessarily. I can’t remember who they all were, but certainly Helen Wolff, who was Kafka’s publisher. They were pretty reproachful with me, because I hadn’t finished my PhD. They kept saying I should at least finish it. I thought so too. I kept asking for extensions because I had another job.

Editor:

Do you remember what the apartment was like?

Adler:

Only to the degree that it was very like my parents house. I think there were Oriental carpets, but I may be making that up completely. I wasn’t really paying attention. Maybe my parents’ milieu and Hannah’s were more alike than I imagine. I remember telling her that I really did not understand my parents’ account of their life in Germany before the war. I just didn’t get it. It made no sense to me. Then she started telling me a story. It was part of a story my father had already told me.

Editor:

What was the story?

Adler:

There was a Jewish family in Germany, and they were very rich. Their last name was Moses, which they changed to Merton. It became a joke in the Jewish community: ‘Have you been to Italy to see the Merton by Michaelangelo?’ So already this is not such an attractive thing. Anyway, it was apparently quite common for wealthy Jews to marry less wealthy Czechs with titles. A girl from the Merton family married a Czech aristocrat named Czernin. So the woman became Trix Czernin. Trix was short for Beatrix. Then during the war, nobody saw anybody. When Trix turned up in America, she was married to my mother’s cousin Bill, who, as unlikely as it seems, was a dairy farmer and war hero. He lived in Amenia, New York. My parents and I went to visit cousin Bill. (In the meantime she had been a secretary to Simenon, so you can see how this gets confusing.) We were all relaxing there together. Suddenly my father said to Trix, ‘What’s happened to the money?’ And she said, ‘Oh, I don’t know.’ And he said, ‘Is it with your brothers or what?’ It’s not a question my father would have normally asked. It’s certainly not a question you would ask of somebody you had a formal relationship with. She said, ‘I don’t know.’ But they hit it off. Right away they knew each other. He said, ‘No, no: what really happened to it? Where did it go?’ She said, ‘I really don’t know.’ He said, ‘You really don’t know?’ She said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘Undenkbar.’ (‘Unthinkable.’) After the war, after everything everybody has gone through, the thing they find unthinkable is that Trix Czernin doesn’t have any money. On the way back in the car I was sort of puzzled by it all. My father said, ‘You don’t understand. It would be as if I.G. Farben or General Motors went bankrupt.’ I thought: No American would be so astounded if somebody failed. I thought, isn’t it strange that of all the things he would react to with real astonishment, as if it were the most amazing thing he ever heard, was that Trix Czernin had no more money.

Editor:

How does Hannah Arendt come into this?

Adler:

Years later I’m having lunch with Hannah. I said, ‘You know something very strange? I don’t understand a thing about my parents’ life before they came from Europe. Nothing makes sense to me. I don’t understand it.’ Hannah said, ‘Listen, I have a story that will explain it all to you. There was this family in Germany called Moses; they changed their name to Merton. That became a local joke: “Have you been to Italy to see the Merton by Michelangelo?” ’ Now this is so terrible, I so regret it: I interrupted. I should have let the story go on. But I started to say, ‘Oh, you know’ – I was going to say that Trix Merton married Cousin Bill, right? But I didn’t get very far with the interruption, because Hannah was going on. ‘Trix Merton became . . .’ I kept interrupting, if only because Hannah said she had chosen this story to explain what my parents’ life was like before they came. I kept interrupting. I even started to recount the conversation Trix had with my father. Hannah said: ‘She has no money?’ She wasn’t interested in any other part of what I was saying. She said, ‘No money?’ Hannah said: ‘Undenkbar.’

Editor:

What? The exact same reaction?

Adler:

She had written The Origins of Totalitarianism. She knew as much about all of that as anybody. And she was ready to criticize the people who collaborated in any way. I’m sure she would have stood up. When one asks now, who would have stood up? – she would have stood up. But to find it unthinkable that somebody lost all her money. It so easily becomes, even in my mind, an antisemitic story. And to think that I interrupted her in telling a story she said would explain everything about my parents’ life before the war.

Editor:

She didn’t finish the story?

Adler:

No! But if I hadn’t interrupted . . .

Editor:

So your father and Hannah were, in some sense, coming from a similar place.

Adler:

They were coming from a similar place. But the difference between Hannah’s family milieu and my parents’ is that my parents were never politically active. I have pictures of both my father and my grandfather (my mother’s side) in uniform in the First World War on the other side. They didn’t really go into battle or anything. I didn’t really quite understand what they did. They said that they were never really soldiers. But my father used to talk about learning to ride in the cavalry.

Editor:

How did you as a German Jew Americanize so thoroughly?

Adler:

Because of my parents. People that my parents knew in Germany, people who came here early enough to survive – they all seemed to my father to be, first of all, Democrats, second of all, on the liberal side, thirdly, to have a sense of superiority over Americans culturally, and in other ways. Americans would ask my father what he thought of this or that. And he would always say, ‘Oh, it’s wonderful. It’s the best, you know, ever, ever anywhere.’ The only exception that he made was for wild strawberries – what a funny thing to say – he said in Germany they might have been slightly better. And the response was, ‘But the wild strawberries here are exactly what we’re most proud of!’ So after that he no longer claimed that German strawberries were slightly better. His friends were all critical of how uneducated Americans were. He said, ‘This country welcomed us. What do we know? Everything’s superior.’ In order to be American, he thought he had to be Republican. And not only him. The whole family had to be Republican.

Editor:

What about the Second World War?

Adler:

All I knew about the war, really, was that we collected milkweed pods for parachutes. There are no milkweed pods in parachutes. We also sold war bonds. We were supposed to sell war bonds. We were reading a lot of comic books. In the comic books, the villains of the war were the Japanese. They were always committing hara-kiri or saying some word like ‘Banzai’. They were always torturing people. Once I mentioned it to my father, and he said, ‘But the Germans were much worse.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about. But then I started reading a different kind of comic book. And there they were all saying, ‘Achtung!’ and ‘Jawohl!’, but it came as news to me that the Germans were the enemy. I found that out pretty late, considering.

Editor:

When did you learn about the camps?

Adler:

It came very late. It came, I think, through movies. I wasn’t allowed to go to the movies much at all. The first movie I ever saw must have been a war movie, because it was called Winged Victory.

Editor:

Why were you not allowed to go to the movies?

Adler:

I don’t know. I just wasn’t allowed to go to film. I was too young to go to film.

Hannah Arendt, 2014 Chantal Joffe, Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro

3

Editor:

What about your connection to Arendt via Mary McCarthy?

Adler:

Mary McCarthy was very nearly my mother-in-law, when I was together with Reuel Wilson. Mary and Hannah were great friends.

Editor:

McCarthy was perhaps her closest friend, no?

Adler:

Yes: she made Mary McCarthy her executor. And it was at times a funny friendship. I remember reading somewhere that when Mary had breakfast with Hannah in New York, Hannah was always having anchovy paste, which I remember, strangely enough, from my own parents. There was quite often anchovy paste. So when Hannah came to stay with Mary, she, Mary, as a friend, put out anchovy paste with breakfast, but Hannah ignored it as though she had never seen such a thing in her life.

Editor:

Why?

Adler:

She didn’t want to have been observed that closely.

Editor:

You have written about Arendt’s attitude toward the public, how she was a public person who didn’t want her privacy entered into.

Adler:

But then why did she leave the correspondence with Heidegger? I would have thought she would have destroyed that.

Editor:

It’s curious.

Adler:

Yet I can imagine her girlhood, and I can imagine that. There she is, she’s waiting outside at night on a bench, even outside his office. If there’s a light in the window, she can come. When there’s no light . . . or it’s the other way around. I don’t know where I read that. But she was eighteen.

Editor:

Another aspect of your relationship with Arendt is the generational divide. You were brought up in the Cold War, in Truman and Eisenhower’s resolutely anti-communist America, whereas she would have had a different introduction to the left. She was not a Marxist by any means, but she would have been familiar with Marxism as an intellectual tradition. She was friends with people like Walter Benjamin. Did you think of her more as a Cold War liberal or as someone with these more left-wing tendencies coursing through her?

Adler:

I didn’t even think of it that way. At the time I knew her there was the New Left. The New Left – she thought she understood them. I really didn’t. She knew the Cohn-Bendit family from Paris, and even offered to fund figures in the New Left like Daniel Cohn-Bendit if they got into trouble. I wrote disparagingly about the New Left, because there was this wonderful movement – I thought at the time – being brought down by these New Leftists.

Editor:

The civil rights movement?

Adler:

Yes, the civil rights movement. For instance, the New Left was mocking Martin Luther King. I kept thinking, ‘Why are they focusing everything towards the Vietnam War, when we have this amazing movement going on?’

Editor:

But Martin Luther King was dead against the war.

Adler:

Yes. But I thought, ‘They’re distracting attention from the only thing that we are winning.’

4

Editor:

You’re usually quite critical in your writing, even of what you admire, but when you write about Arendt there’s a kind of fealty. It’s as if you’re suddenly thrust into the position of trying to size up her historical stature.

Adler:

I knew I loved her as a friend. I knew I admired her as a writer and as an intellectual and as a human being, but I didn’t have what I presumptuously call ‘understanding’. I didn’t really understand her at all. Well, ‘at all’ is going too far, but I didn’t really understand this very complicated cast of mind. I remember her saying that it was just as well that people died before they became too old, because they get too dogmatic, or they get too boring. She was really saying something much more complicated, which I’ve already forgotten.

Editor:

Do you have other memories of Arendt?

Adler:

Strange things. She has a line where she says: ‘Events, by definition, are occurrences that interrupt routine, processes, and procedures.’ Doesn’t that strike you as brilliant? I have a memory so distinct, but I don’t see how it could have happened. I was living on 49th Street, three floors up. Hannah is coming up the stairs with a German Shepherd. She knew I wanted a dog. I can’t remember where she got it. How could I do anything but say how grateful I was? Then she said, ‘Of course you have to medicate his ears.’ The phrase is so strange that I couldn’t be making it up: ‘Medicate his ears’! Now I have very strong feelings about dogs. But somehow I didn’t want that one. Nor did I take it in the end. So that’s it.