– Deion Sanders, Power, Money, & Sex: How Success Almost Ruined My Life

1

American football was never invented; it was fashioned by committee, over a span of decades. The first college All-Americans list went to press in 1889, seventeen years before the game’s adoption of the forward pass, thirty-eight years before the first recorded sighting of the ball now claimed as its namesake. 1905 was a catalyst year, the year the sitting president of the United States got involved. Teddy Roosevelt counted himself an advocate for the sport, professing the belief that the game’s inherent violence was wholesome for the character of American boys. When he spoke on the subject he made vague and ominous references to future difficulties, saying the boys would need to be tough for the times to come. Yet it had been brought to his attention that the sport was infected with an ungentlemanly virus, that cheaters and hoodlums plagued collegiate football, and that schoolboys were being coached in the art of ‘mucker play’ – the deliberate injuring of an opponent in order to remove him from the game.

There were reasons for concern. In the wanton day of mass-formation play, of the Princeton V and the flying wedge, football was averaging about fourteen players killed per annum. Chancellors, athletic directors, and boards of overseers were under pressure to ban the sport. Roosevelt wanted to avoid that outcome. Three universities controlled the rules committee of the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA): Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, and so Roosevelt summoned representatives from all three to meet with him at the White House on 9 October 1905. Football was on trial, said Roosevelt. To save the game, the IFA would need to reform it. There was only the matter of how.

The forward pass was suggested. At the time, a player could throw the ball backwards or laterally but not upfield. The team on defense could commit all its players to attacking the offense’s backfield, and the offense didn’t have much chance outside of out-bludgeoning the defense. Scoring was rare and far from assured. Apart from the violence, the games were uneventful slogs, melees, devoid of finesse. Some hoped a forward pass would change things – players would be more spread out; the game better balanced, safer, more dynamic. With more field to take into account, teams would not concentrate into mass formations, and defenses would have to commit players to guard the area behind their lines.

The Yale contingent balked at the idea. They suspected Roosevelt had an ulterior motive: helping his alma mater Harvard (their arch rival) gain an advantage over them. Representing Yale was Walter Camp, the (unofficial) director of its football team. Camp was no lightweight: the line of scrimmage; the eleven men on a side (down from fifteen); the safety penalty and it being worth two points; the point system itself – all these and more were his contributions to the genesis of the game. He had been in attendance at the 1873 meeting when the IFA was formed; his name was on the rule book; in 1892 Harper’s Weekly had called him ‘the father of American football’. It would be a great help for Roosevelt’s reform initiative if he could talk Camp into throwing his support behind it.

This seemed within the realm of possibility. Camp’s crowning achievement, the line of scrimmage, had been a player-safety measure. When he took it to the Rules Committee, he brought statistics that showed the greatest number of injuries happened in scrums. If Camp had been for improving player safety then, it stood to reason he could be coaxed to be so again. But the forward pass was anathema to Camp, for whom the essence of the sport was the ground attack. In his game, an edge was sought by forming as many of your players into as fine a point as possible and running it through the adversarial body. Football strategists of the day thought in terms of phalanxes and legions, studied battle formations back to ancient Macedonia in search of an insight, some irresistible spearhead lost to time.

However much Roosevelt dug him, Camp wasn’t won over. He wasn’t some uneducated sucker – he was a Yale man, a member of Skull and Bones, and the top power broker in football, a schemer with a $100,000 slush fund who for decades had been calling the shots for the Eli of Yale from his office at the New Haven Clock Company. The White House meeting adjourned with no promise from Camp beyond a commitment to join the others in issuing a public condemnation of mucker play, and a pledge to clean up the game from any disgraceful, unsportsmanlike or immoral element.

Roosevelt was quick to declare victory. In a letter to Camp, he expressed effusive satisfaction, writing of his trust in the integrity of the football men and in their ability to enact reforms that would restore the game to good standing. Seven weeks later, three players were killed, all on one Saturday, 25 November 1905. The names of the dead ran in the Chicago Tribune: ‘Those Killed Yesterday . . . OSBORN, CARL, 18 years old, Marshall, Ind.: killed in game of Judson high school vs. Bellmore high school; injured in tackle, rib piercing heart and killing him almost instantly . . . MOORE, WILLIAM, right half back of Union college; killed in game with New York university; fractured skull in bucking the line: died in hospital . . . Fatally Injured . . . BROWN, ROBERT, 15 years old, Sedalia, Mo.; paralyzed from neck down; dying.’ The headline read: football year’s death harvest: records show that nineteen players have been killed; one hundred thirty-seven hurt.

Over that Thanksgiving break, Columbia, Duke, and Northwestern universities went ahead and banned football, having lost patience with the Rules Committee. Predictably, Roosevelt was outraged and vowed action. Using his executive powers as commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces, he ordered the military academies to come to their own consensus on a new set of rules. He wasn’t the only one making moves. Chancellor of New York University Henry MacCracken and Harvard coach Bill Reid were arranging an emergency meeting of sixty-two colleges and universities. The newly assembled body called itself the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States. Its first order of business was to take a vote on whether or not to ban football. A general ban fell short by two votes. The next step was to revise the rules. Camp had been usurped – not being present he was unable to argue for the sanctity of the ground attack. Legalization of the forward pass was a foregone conclusion.

The first legal forward pass was attempted on the first weekend of the 1906 season. Bradbury Robinson of St Louis University tried it out against Carroll College. The pass fell incomplete, which made the play illegal. In the 1906 rules, a forward pass was legal only if completed – an incomplete pass was a penalty, and the penalty was a turnover, which meant the passing team lost possession of the ball. Here was the problem: the forward pass had only been legalized by half measures, relegated to the status of a trick play, a play you ought to be embarrassed to try, that you should be penalized for if unsuccessful. You could try to shoot the devil in the back, but if you missed then the devil got the ball and, in the name of the father of American football, God willing, rammed it down your throat, ground-and-pound style. There was still no penalty for pass interference, which meant the defense was at liberty to tackle the receiver mid-route. Anybody stout enough to run a pass route and not get knocked down was unlikely to have enough speed to get open and vice versa. Most teams stuck to the ground game.

Camp continued politicking for the repeal of the forward pass, on the grounds it left the outcome of games too much to chance, that an undeserving team might win. His time dictating the precepts of the sport meant that he still held sway over football men throughout the country, and many were not quick to relinquish the philosophy they had imbibed from him. But the problem for opponents to the forward pass was that players kept dying. The 1909 season saw twenty-six players killed in action. As had been going on for thirty years, most of the dead were high-school players – to put it another way, children – and less and less did people care what the Father of American Football was saying about the essence of the game.

The 1910 season was inaugurated with the forward pass on equal legal footing as run plays. The new era could now begin in earnest. Purists of the day said American football was ruined forever.

2

Out of these ruins green shoots did grow, and a new game flowered and spread. The forward pass proved to be an equalizer. Before the forward pass, whoever could acquire the most body, the most beef, was the favorite to win. Now speed, agility, timing, and field vision counted almost as much as pure violence. Glenn Scobey ‘Pop’ Warner perceived these things, since he had an interest in working them to his advantage. When he first arrived at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to take over the job as head coach of the Carlisle Indians, the team had already competed against top schools and held their own well enough. But Carlisle’s teams tended to be underweight, shorter in height and reach than their competition. To overcome this they outmaneuvered, out-schemed, and out-executed their opponents. Warner was an established journeyman coach, with a reputation for running up the score on the other team. He was ready for the forward pass. In 1911, Warner and Carlisle went 11–1.

The next year, the Carlisle team won its most poetic victory: 9 November 1912, Carlisle Indian Industrial School versus Army at West Point. Three thousand were in attendance, and the symbolism not lost on one of them. Warner professed himself not one for pregame speeches, but in this case he made an exception: ‘I shouldn’t have to prepare you for this game, just go read your history books. Remember that it was the fathers and grandfathers of these Army players who fought your fathers and grandfathers in the Indian Wars. Remember it was their fathers and grandfathers who killed your fathers and grandfathers. Remember this, every play. These men playing against you are the soldiers. They are the Long Knives. You are Indians. Tonight, we will know if you are warriors.’

The game was remembered for its roughness. Carlisle got off to a shaky start, shut out for most of the first half by a score of 6–0. The second half was another story. Warner’s star tailback Jim Thorpe ran riot. The Army team went to pieces. The Cadets targeted Thorpe. Mucker play. But Thorpe was ‘impervious to injury’, and the attention Army paid him freed up Alex Arcasa at halfback to score three touchdowns. Army kept trying to move the ball on offense and showed a spark of life when freshman halfback Dwight ‘the Kansas Cyclone’ Eisenhower ripped off a twelve-yard run almost to midfield, not quite into Carlisle territory. Eisenhower tried to knock Thorpe out of the game, went for him so hard he missed the mark when Thorpe juked him and crashed into the Army halfback Leland Hobbs instead. Hobbs had to be carried off the field. Eisenhower sat out the rest of the game with a knee injury – the Kansas Cyclone would never play again. Carlisle didn’t let off after that. The game was called a few minutes early due to a lack of light. Carlisle beat Army 27–6.

The Army team captain, first-team All-American tackle Leland Devore had been disqualified for unnecessary roughness. Devore would go on to take part in Black Jack Pershing’s ‘Punitive Expedition’ against Mexico in 1916, and then to serve as an infantry officer in France, where he would be wounded, one of several American football standouts to be injured in the Great War. The linebacker, Eisenhower, missed that one; perhaps his knee kept him out or perhaps he was just lucky. The Second World War he wasn’t as lucky. The Army put him in charge of Overlord; he was smoking five packs of cigarettes a day; he had an affair with his secretary; he tried to resign; the Chief of Staff laughed in his face, told him to get real, told him to mash the button. And he did the deed. Americans were so grateful they elected him president, and they liked the job he did so much they elected him again. At the end of his second term, in a speech to the Republican National Committee, his thoughts wandered to his counterpart from the Carlisle–Army game of 1912: ‘Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.’

Such was the stature and reputation of Wa-Tho-Huk (Bright Path), government name James Francis Thorpe, of the Sac and Fox Nation. Jim Thorpe became the greatest football player of all time. He was among the first players for the National Football League, a new professional league founded in 1920 – now the highest-grossing league in American sport.

Thorpe went on to fame and glory – Pop Warner to a season of infamy. He was discovered by the Department of Interior to be in league with Carlisle superintendent Moses Friedman playing fast and loose with the money. Carlisle was foul to begin with, the school being an instrument of genocide. The students, young Native American men and women, were taught that their cultures were inferior to European culture, forced to disown their customs and rituals and to attend Christian religious services. The food was rough, the discipline strict, the books cooked. Of the over 10,000 youths to attend Carlisle since its founding, hundreds had died and many were buried there, far from home, under names that were not their own.

The public image of Pop Warner, surrogate father, leader of men, benevolent genius, progressive white man: it was exposed as a fake. The players knew who Warner was. They knew he was getting rich off of them or else he wouldn’t have been there in the first place. Perhaps the most striking example was the presence of Warner in hotel lobbies selling the comp tickets the home team gave the Carlisle team when they came to town to play. One Carlisle football player testified that he saw Warner sell seventy-five such tickets on one occasion, seventy-five being the total number of tickets the home team had set aside for the visitors. The player said he never found out what Warner did with that money. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was closed down in 1918. Taken over by the Department of the Army, it was converted to Base Hospital 31. Carlisle was forgotten. Army had its revenge.

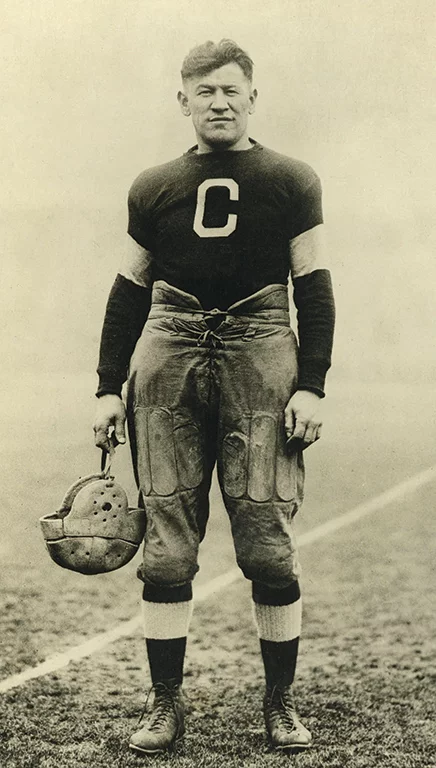

Jim Thorpe playing for the Canton Bulldogs, 1915-1920

3

And so they broke the mold when they made Jim Thorpe. He was the first football player of international fame. At the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Thorpe won gold twice, for the penthalon and the decathalon, and the King of the Swedes, Gustav V, declared him ‘the greatest athlete in the world’. To have have an athlete of Thorpe’s stature suiting up for games was a windfall of legitimacy for the sport.

Thorpe was the model figure that would define American football for a generation: the star tailback. See, the quarterback, the present day’s most exalted position in the sport, he wasn’t drawing much attention in those days. The QB’s role was more as a blocker. Even with the advent of the forward pass, the QB’s physical interaction with the football was largely limited to receiving it from the center and giving it away as quickly as he could. The center would ‘snap’ the ball – originally, by rolling it backwards with his heel; later on, by passing it back through his legs into the hands of the QB – and the next move would usually be for the QB to toss pitch or shovel pass the ball back to a teammate deeper in the offense’s backfield, getting the ball away from the opponent’s defensive line as it tried to crash in. The QB could not legally advance the ball forward of the line of scrimmage before moving laterally five yards to either side of the spot the center had snapped the ball from.

The one privilege of being quarterback was that, as the conduit of the ball to the playmakers in the backfield, it was a leadership position. It was the quarterback’s job to manage the game, to see who on his team was hot, to see where the defense was weak and make adjustments, call the right play. The quarterback did the snap count. The quarterback held the ball for the kicker on placekicks. The quarterback was an indispensable ball-handler, much as he is now.

But there was a stretch of roughly thirty years – from the 1920s through the 1940s – when the quarterback wasn’t getting a lot of touches. He called the plays and the signals, he blocked, maybe caught a few passes, he held kicks. But he hardly did any passing. The tailback was the focus of the offense, the feature back. Not only could he be the primary rusher, he could be the primary passer, too. And so for a while the sport revolved around the tailback, and the dominant tailbacks were easy to make famous. Thorpe played in the single-wing scheme, as designed by Warner. The tailback and the fullback started five yards deep in the backfield, on either side of the center, so that the center had the option of snapping the ball to either of them. The QB would be lined up behind the tackle. A wingback, the namesake of the formation, would set up off the back foot of one of the ends. The QB and the wingback could block, or they could break upfield and look for a pass. The games tended to be open, with lateral running. The tailback had to go five yards to a side of the snapper before he could turn upfield, the backs would run a sweep, the three backs lead-blocking for the tailback. It was vital to beat the defense to the corner. The runner had to turn the corner and break into the defensive backfield to get free.

To have a track star like Thorpe, a player with that kind of speed, was a decisive advantage. The opponent’s defense had to work hard to have a chance to stop the run, and yet it could not fully commit so long as the offense had the option of throwing a forward pass. The wingback could always throw a block first, say, on a sweep, and then dump the defender and break off into a pass route upfield. The threat kept defenses off balance. The game was becoming more tactically complex. And Thorpe was up for that. He could kick the ball better than anybody. He could throw the ball well, as he had thrown the discus well, and the shot put. His prowess was the means by which the game’s next phase was demonstrated.

The game had now begun to resemble its current form. There were still many limitations in place to hamper the passing game. Since 1906 the field had been marked into grids, five-by-five yards, and a forward pass couldn’t cross the line of scrimmage in the same grid as the ball was snapped in. The turf conditions were generally bad. Games played in the rain would devolve into a mostly inert brawl, purchase could not be gained for love or money, the teams wallowing in muck. The thirty-yard reception wasn’t yet visible on the horizon. Again, the football – the actual ball itself – still hadn’t been invented. The sport was played with a rugby ball, no matter what anybody says, which was more difficult to throw – particularly, to spiral – so there were lobs or there were forward laterals, a bit of razzle-dazzle, like a game of keep-away, one that looked at home on silent-movie reels, maybe with some stride piano to accompany it, or a slide trombone.

For all its grasping awkwardness, as the sport struggled to loose itself from the primordial mud of its creation, it photographed well. The chaotic brawl, when distilled into a single photographic frame, assumed a gravitas that not even the live action itself could match. The football player became more than just a chauvinist preppy who liked to hurt people. Thorpe marked the point in time when the football player began to symbolize something higher than a game. Regardless of how he felt about it, a myth was constructed around him.

As it often did then and would continue to do, baseball helped football along. Thorpe had played baseball well enough at Carlisle to be considered a viable big-league talent, and the National League’s New York Giants (of baseball) were eager to sign him. They knew Thorpe’s celebrity would sell tickets, at least for a while, perhaps for a long time, should it turn out he could play. In 1913, the Giants signed Thorpe to a $6,000-a-year contract, a record payout for a rookie at that time. He didn’t play very well. It could’ve been he struggled to bat at a big-league level. It was rumored he couldn’t hit the curveball. It was rumored Giants manager John McGraw had spread that rumor.

In the 1951 motion picture Jim Thorpe – All-American, Thorpe’s failure to make good in Major League Baseball is blamed on a lack of discipline and an incurable stubbornness of character. In the scene that’s supposed to demonstrate this, the actor who plays McGraw fines Burt Lancaster (as Thorpe) $50 for ignoring a signal to bunt. ‘I got a hit, didn’t I?’ says Lancaster. ‘That’s not the point,’ the actor playing McGraw says, ‘this is a team game.’ What the film fails to mention was that if this exchange had in fact happened, then there would’ve likely been a piece of rope in McGraw’s possession at the time – a ‘good luck charm’ he carried with him – which had been used in the lynching of a Black man, because McGraw was one of the monumental racists of baseball history. Which is all to say that Thorpe’s difficulties could’ve been down to McGraw’s Giants not being the ideal team for Jim Thorpe.

Or it could be that Jim Thorpe was never that interested in playing baseball. He showed up, and he sold the tickets. He hacked away. But what was there for Jim Thorpe to love in the game of baseball? He wasn’t the pitcher on the mound. The game’s outcome wasn’t entirely riding upon his shoulders. Consequently he must have felt frustrated, squandered, too talented for his role on that team.

In gridiron football, not only did the outcome of any given game depend on him, the survival of the league he played for depended on him. The Olympics had made him into a celebrity, yet at the same time baseball was baseball, the ‘American Pastime’, and to have a high-profile major-leaguer like Thorpe split his time between the premier sport in American culture and football was a life-sustaining elevation for the new professional teams. Thorpe was making $250 a game, setting a new high for what qualified as top dollar in football. He played for the Bulldogs of Canton, Ohio. He was also head coach. Before signing Thorpe, the Bulldogs’ attendance receipts were averaging around 1,500 spectators. Thorpe’s debut saw attendance jump to 8,000. He stayed with the team from 1915 through 1920, the last being the year a new pro league was founded in Canton, the American Professional Football Association, which, two years later, was renamed the National Football League.

4

In the US presidential race of 1916 the incumbent candidate, diehard Princeton football fan Woodrow Wilson, ran on the slogan ‘He kept us out of war’, and he got re-elected like that, knowing full well he was going to take the country to war immediately, wasn’t even going to wait until after the midterms. Since there was going to be a draft, there’d need to be a fitness regimen, something to whip the boys into shape. President Wilson tapped Camp to come up with something. Camp came up with the daily dozen, twelve exercises which, if done regularly, could transform a young man’s physique, change him from a fledgling into a man who could kill you with just his bare hands. Football was part of the program. At the forts, camps, and bases throughout the country, recruits from all over were playing American football. When the war ended and the boys came home, they came home knowing a lot more about football than they did when they left. It was the beginning of a long and beautiful relationship, the triad of American football, the American war machine, and the American male.

There’d be more room yet for American football on the national stage, and room too for football stars, tailbacks like Jim Thorpe, only different. In the 1920s there was Red Grange. Born Harold Grange, he developed a knack for nicknames early. Harry Grange wasn’t going to get his name in the papers, so he became Red Grange, then when he was a high-school standout he became the Iceman of Wheaton, because he worked part-time as a deliverer on an ice truck. Then he went to play for Illinois, the Fighting Illini. He came into the game in a fog, looking like a ghost, and the ghost could run the ball, and so they called him the Galloping Ghost. He could run, he could throw, and like Thorpe he went pro. He left school early, the star tailback cutting out on his team. But Red was right: why kill yourself for the school colors when you could be making a killing on the free market playing for the Chicago Bears in the NFL? The newspapers howled about it, the old boys dog cursed him, but the public didn’t care. The public didn’t go to college.

Like Thorpe, Grange legitimized the professional leagues. The best football player in the country ditched school to wear a fur coat and drive a Cadillac. What wasn’t there to love about that? This was the democratization of the football star. It wasn’t esoteric East Coast college-boy role-play anymore. It was something the man in the street could get behind. It reminded him of war in ways that were good. It made him feel tough to know that there were tough men making money playing ball and eating steaks two inches thick. It gave him something to dream about. It was upward mobility embodied, the tailback running into the pile, shedding tacklers, breaking into the open field, running bastards over, free now, running free into the end zone, still running all the way through the tunnel, out of the stadium, into the limousine, to the best table and the best club in town, dinner and a few drinks, see everybody, and then home to the big house on the hill.

Red Grange could be you. Red Grange, the boy who’d been born in the logging camps of Forksville, PA, the boy whose mother died and whose daddy went home to Wheaton, IL, and got a job as a policeman. Red Grange, just a regular guy. If you weren’t Jim Thorpe, you could be Red Grange. In the 1930s you could be the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame. Improvements in motion-picture technology helped to get the word out, and with the pads on the boys looked impressive. The headgear reminded people of aviators. If you were trying to sell a few newspapers, you couldn’t hurt your cause by bringing God into it, at least when His team was doing good. This proliferation of publicity would have a lasting impact. Had it not been for the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame, a Catholic like John F. Kennedy probably couldn’t have been elected in the 1960 presidential election. Kennedy was standing on the shoulders of giants, four football players who had put in the work in South Bend, Indiana, and endeared papism to even the most jingo-Protestant hearts.

Then came the aptly named Bronko Nagurski. Like Grange, Bronko played for the Bears. They were teammates from 1930 to 1934; Grange at tailback in the sunset of his playing career, Bronko at fullback, just at his outset. They inadvertently ended the tailback era of football together, in a game in 1932. Nagurski faked a run, dropped back and threw a touchdown pass to Grange. It was the NFL’s first ever playoff game, the Chicago Bears versus the Portsmouth Spartans. The game had been moved indoors at the last minute due to a snowstorm, and so the referees didn’t have the benefit of the grid to keep players (like Nagurski) honest. The Spartans complained to the league officials on hand, saying that the play had been illegal, that Nagurski clearly had been closer than five yards to the line of scrimmage when he’d thrown the pass. The points had to be taken away, they said. The league’s answer was to change the rule. The grid went out the window, replaced by the hash-mark system that’s used to mark the playing field today. It was the beginning of the modern era, part of which would entail player specialties – e.g. a separation of powers between the feature running back and the passer; between the fullback and the kicker, etc.

Bronko and Grange were the last of their generation. Never again would an offense’s plans rely so much on the effort of one player, a combination of the modern game’s running back and quarterback and kicker in one position. There would be no more iron men like that, a back that could carry the whole team on his shoulders, run the ball, score all the touchdowns, pass upfield, kick a field goal, go out for a pass just to mix things up, do a little upfield blocking – and in the days of the one platoon system, when teams didn’t rotate players when they went from offense to defense, the eleven players who started the game meant to play every down. The game was a struggle of violent endurance. The players were workhorses, and they played through injury. They didn’t want to lose their jobs. It was a perfect allegory for the times.

Who was this tailback? This Achilles? Was he John Henry? Was he a try-hard? A fat cat? A warrior prince? A scab? Did it matter who won? Why did these men, these guards and tackles and ends and centers – men who weren’t getting paid like the stars in the backfield were getting paid – why did they go out and break their neck for the tailback so he could score his touchdown, so the coach could win, so the owner could win, so the city could win, so the fans could be happy? Because it was beautiful to see. Bronko, the ultimate expression of an era of the running back, tearing into the wind on a frozen field, north Chicago, Wrigley Field, the wind coming in off the cold lake, wind that could freeze a man to death, but not Bronko. Bronko liked to go to war like that, busting linebackers in the chops, went to war for his team, for his buddies, for his people – the Polacks, in this case.

Bronko played until 1937. Everybody knew he was going to be the last star of his kind. The rules had changed and teams needed to adapt to new kinds of offense, or they would lose. It was the end of the grid game. It was the professional sport wresting control of the game from the collegiate leagues. The team owners didn’t have universities backing them, they had to make money, and they figured it’d be nice to see more scoring.

So the NFL introduced the modern ball. The 1934 ball was modified from the more rugby-esque style of ball; the altered version had tapered ends, making the ball easier to grip and, therefore, easier to throw a spiral. It must have seemed as though the forward pass were being invented all over again. The game changed suddenly and profoundly. In the 1934 season, the leading passer in the NFL was Arnie ‘Flash’ Herber, who threw for 799 yards (that’s passing yards gained from scrimmage). In 1937, ‘Slingin’ Sammy’ Baugh threw for 1,127. In 1945, Sid Luckman threw for 1,727 yards. In 1955, Jimmy Finks threw for 2,270.

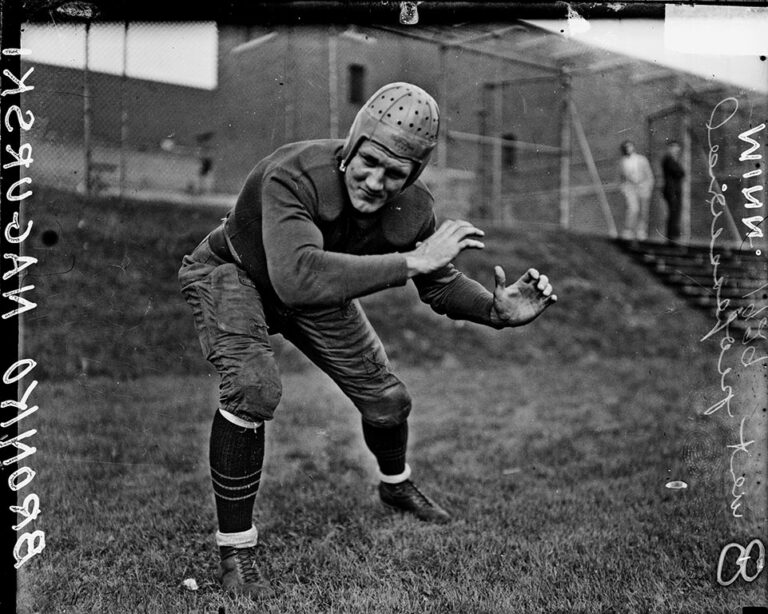

Bronko Nagurski, 1929, Chicago History Museum

The quarterback knew what everybody’s role in every play was – who should zig, who should zag. So the quarterback was the natural choice to be the offense’s dedicated passer, provided he could throw – like really throw. If he couldn’t really throw, he wasn’t going to play quarterback anymore.

The QB got billed as the star of the show. All that was missing was television. It wasn’t long in coming, almost as though it had been waiting. 28 December 1958 saw the first broadcast of the NFL Championship Game between the Indianapolis Colts and the New York Giants. The Colts won in sudden-death overtime. Forty-five million people were said to have watched the game, and afterwards American football was made. No power on Earth could stop it from becoming the most popular sport in the country, because the future of sports was on television, and football seemed made for TV. The TV would never do justice to the fastball or the curveball. The baseball field was too big to fit on the screen, you were looking one way, then another way, or you were looking one way, then this way, or you were looking from so far back you couldn’t see anything. The TV was better suited to spectacular violence – football.

It helped that the football schedules formatted so well to network programming; a reasonable number of games that did not take up too much airtime, yet filled enough of it every year so as to be indispensable. Baseball teams played 154 games a year. That was a lot of TV time to spend on keeping up with a single team. NFL teams only played thirteen games a year, not counting the playoffs. College teams played ten, eleven games. The colleges played Saturday, the pros Sunday. You could theoretically follow two football teams closely and still hold on to your job. This was now the American century, and the war machine was always in the wings.

War was embedded deep into the sport, everywhere in the vernacular. The sack. The wedge. The line. The blitz. In its infancy, football had reveled in its homage to pre-gunpowder war, to melee combat. The tailback era alluded to war on horseback, to the cavalry. The Galloping Ghost. The Four Horsemen. The modern game, the quarterback game, looked for its reflection in aerial warfare. Receivers ran ‘routes’ or ‘patterns’. Teams had their offensive and defensive schemes. There was the ‘long bomb’. Bobby Layne was ‘the Blond Bomber’, Daryle Lamonica was ‘the Mad Bomber’. Footage of teams studying plays on the board, the players sitting at little desks in a classroom, brought to mind bomber pilots being briefed by their commanders with maps and aerial photographs of targets. It all made for compelling television. America was strong, and so was American football. It was on Sunday, just like church. It was a religious service now. The religion was America. And America was the business of war. It seemed like it could go on forever.

5

It was no coincidence that the quarterback always used to be a white guy. The same year the so-called modern era of American football began, 1933, was the same year the NFL locked in its period of infamy, the era of the ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ – the unspoken pact between NFL owners not to sign Black players to contracts. College football had never barred Black players from playing because it didn’t have to. How many Black men were admitted to Princeton or Harvard or Yale or Columbia? There were a few Black players: William Henry Lewis played for Harvard, William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson for Amherst, George Jewett for the University of Michigan. Paul Robeson played for Rutgers. It wasn’t until the sport got big that the bigots began to take notice of who was playing in the games.

The bosses were putting the screws down everywhere. Fascism was on the rise, at home and abroad. The police were for sale. The means of production were not up for discussion. George Preston Marshall, owner of the Boston Braves, was intending to move the team to Washington, D.C. In 1933, Washington, D.C. was a segregated city, as it would be up until 1953. And the owners were worried a race riot would break out if Black players were getting paid while white men were out of work.

Segregation stuck for twelve years. In that time there was another world war. The second. Another Roosevelt was president. Franklin Delano. Traitor to his class, they said. He sent his segregated armies of democracy to fight overseas. Twenty-one NFL players were killed. The rest were in pieces, shot up or shell-shocked, missing toes, doing morphine, committing suicide, working for General Motors.

Segregation made American football meaningless: it kept the best players from playing. In 1946, the NFL was officially reintegrated. But it is difficult to place an exact date on when the NFL was actually desegregated, because internal segregation persisted. Black players were shut out of leadership positions: quarterback, middle linebacker. The hostility ended up backfiring on the bigots. In order for a Black man to make it onto the football field, he had to be multiples better than his white counterparts. And when it happened, people noticed.

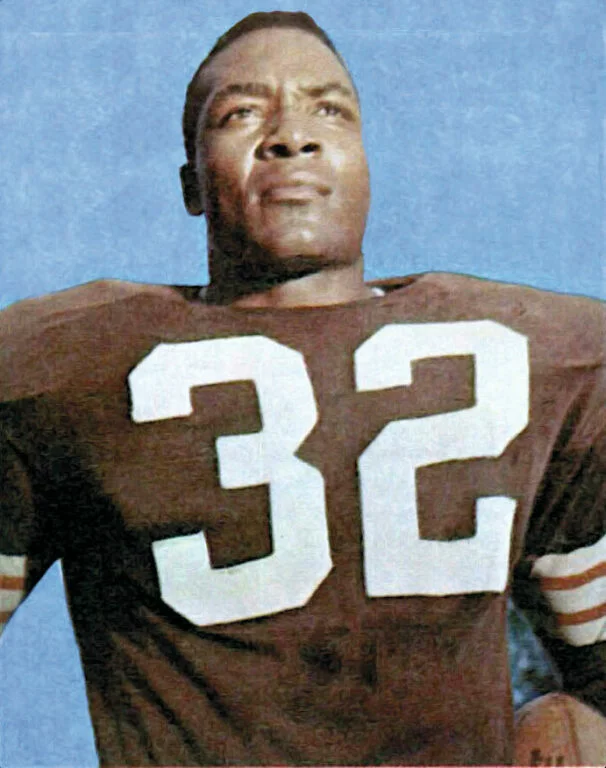

Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns on a Topps football trading card, 1959

For example, Jim Brown. He ran the ball and kicked field goals for the Syracuse Orangemen and would’ve won the Heisman Trophy, had the Heisman Committee given it to the best football player that year, and not the best white football player. But he had his revenge when he turned pro in 1957. In his first season, he set a single-game rushing record – 237 yards – that stood fourteen years, and a rookie rushing record – 942 yards over twelve games – that stood forty years. He won Rookie of the Year and his first MVP. Next he broke the single-season rushing record, surpassing Steve Van Buren by just short of 400 yards. The only year he didn’t win the NFL rushing title was 1962, when he was hampered by injury. There was nothing on the field that Brown couldn’t accomplish. He retired at age thirty, having already cemented his reputation as the greatest American football player since Jim Thorpe, and while he was still in his prime.

His retirement was international news. Brown was in England, filming The Dirty Dozen, about a band of military prison convicts sent behind enemy lines to kill the Nazi high command at a cocktail party in occupied Normandy. In the film, Jim Brown’s character Jefferson sacrifices his life to drop hand grenades through the air shafts onto the heads of Nazi partygoers cowering in a bomb shelter. There were filming delays, and the project was running behind. Brown hadn’t intended to miss his team’s training camp, but his hands were tied. The Dirty Dozen wasn’t a B-picture. It had blockbuster talent: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Donald Sutherland, John Cassavetes, Telly Savalas, Ernest Borgnine, George Kennedy, Trini Lopez, Robert Phillips. His team owner wasn’t thinking about that. Art Modell let it be known he would fine Jim Brown for every day of training camp he missed. The message wasn’t well received. Brown had been carrying Modell’s team on his back, now going on nine years. He decided that he would rather retire from football than deal with it anymore. His kiss-off to the NFL made him more famous than he had ever been while playing. He retired in 1966. Twenty years after the integration of the NFL, a Black man was turning the league down.

6

The NFL didn’t take the lead in integrating football. That honor belonged to another league. In the late 1950s, Lamar Hunt, heir to the Texas oil fortune of his father, the arch-conservative H.L. Hunt, was determined to buy a football team. H.L. Hunt had bestowed a trust worth more than $500 million to his son, so that Lamar could be ‘self-employed’ and build something of his own. But the owners of the NFL didn’t want him in the club. There were stories about him, that he and his daddy were mobbed up; later there would be talk of connections in Dallas, connections in Washington, connections to gunmen, guys with names like Ruby and Oswald.

When the NFL wouldn’t expand, Lamar went looking for a team that might be for sale. There were the indigent Cardinals of Chicago. The owner Walter Wolfner rejected his offer, but he told Hunt about who else had tried to buy his team and where to find them. Hunt went down the list Wolfner provided. He made a proposition to Bud Adams, another millionaire oilman’s son. Hunt laid out his plan: if they both wanted to buy a team and so did some other guys, and if the American public couldn’t get enough of football on TV, why couldn’t a new league succeed? Denver and Minneapolis were in, but for the league to have a national image, he’d need teams in New York and LA. Barron Hilton came on board to found the LA Chargers. The team that eventually became the New York Jets was owned by Harry Wismer.

The American Football League was formed in 1960. From the beginning, the teams included Black players. It also had different rules that improved the game – e.g. the two-point conversion, an import from the collegiate game that wouldn’t be included in NFL football until the 1994 season. But the real level up was the way they did TV. The new league struck a deal with ABC. They broadcast their games right after the NFL game went off on NBC. The AFL broadcast was self-evidently better than the NFL broadcast. They featured more close-ups and new mics were developed to pick up the sound of the punt. They put the players’ names on the backs of the jerseys, and the broadcasts included interviews with players before and after the games. The half-time show was not infrequently a literal circus performance, with elephants marching on the field. If Hunt liked it, it was going to happen. He was the one who knew the words ‘Super’ and ‘Bowl’ belonged together. The AFL teams went aggressively after the loyalty of their locality when there was a rival outfit in town. Most of the early AFL stadiums were down at heel, but they also had fewer rules. The game was a party. Fans brought barbecues into the stands with them.

AFL viewership was helped by the NFL’s blackout policy, which barred home games from being broadcast in the area where they were played. What was on TV were the AFL games. In 1961, the AFL came up with another innovation to drum up fan support: the All-Star game. The fourth AFL All-Star Game, in 1965, was to take place in New Orleans, a state that lagged behind in civil rights, evident from the moment the players arrived. They were told they’d have to arrange rides to their hotels with a ‘colored cab’ service. The first evening before practice the players went out in the French Quarter, and all the Black players were turned away from clubs. They skipped practice the next day to have a meeting.

The Black All-stars from both teams were adamant about a boycott. Veteran player Cookie Gilchrist, six foot two and 225 pounds, called for a vote, adding, ‘You all know I will kick the ass of whoever votes to stay and play.’ The result was unanimous. White players Ron Mix and Jack Kemp tried to persuade the Black players to limit their protest to making statements to the press. But they weren’t playing. The players elected Ernie Ladd, the largest player among them, at six foot nine and 325 pounds, to announce the boycott. The game was duly moved to a stadium in Houston.

7

By the end of the 1950s, the success of AFL had begotten a war between the leagues. The NFL’s players used this as leverage to help themselves. Until 1956, players had no benefits, and owners had free rein to do as they wished: no minimum salary, no health insurance, no pension, no life insurance, no pay for pre-season games. This all changed when the Green Bay Packers were refused clean jocks, socks, and uniforms for two-a-day workouts that summer. The Packers organized, and joined efforts already under way in Cleveland. The National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) was formed in 1956, though it was not recognized until 1958.

At the union’s first official meeting, the list of requests was basic: a minimum salary at $5,000 per year, a uniform per diem for players and equipment, and, most importantly, salary for injured players. They submitted requests and waited for a meeting with NFL owners that never came.

The AFL formed its own union in 1964, which only worked to strengthen the demands of the NFLPA: there was the expectation that players could use the threat of signing with an AFL team to have their demands met. Players wanted a pension plan, but the owners struck back, adding a clause that any player would lose his pension if he went to another league. Any remaining hope that the two unions might aid players through collective bargaining turned to dust when, in 1966, a merger between the AFL and NFL was announced. Both unions opposed the merger, citing antitrust laws, but their meager funds weren’t enough to mount an effective fight against the now all-powerful combined NFL.

The merger was not officially recognized until 1970 and the two unions still operated separately for a time – a mistake, as the owners were able to play the unions against each other. They struggled to communicate with their own membership and the NFL refused to discuss their agenda. In 1970 the players went on strike, after a lockout by the owners. But the owners threatened to cancel the season, and the strike lasted only two days. An agreement was reached: modest increases in minimum salaries, with dental benefits added. For the first time, players were given the right to have agents. Biggest of all: the agreement gave players representation on the Retirement Board and more ability to fight for injury grievances.

In 1974, new negotiations began. A system had been put in place since the NFL’s beginning in which players were expected to accept their pay, perform their roles, and be grateful. The NFLPA prepared to go after the so-called ‘Rozelle Rule’, named for NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, who had final say over a player’s worth and where they played, a power wielded to such an extent that free agency – the players’ ability to freely negotiate contracts with other teams – essentially didn’t exist.

The owners and management drummed up anti-union sentiment with a paternalistic approach, working the term ‘NFL family’ to death. ‘No Freedom, No Football’ became the striking players’ battle cry. The strike lasted forty-four days. Things came to a head on

27 July, when players picketed the Hall of Fame Game in Canton. By 10 August, the owners still had not agreed to a single demand. Finally, in frustration, the players called off the strike. They took the battle to the courts in a standoff that lasted more than three seasons. But each time the NFLPA was victorious in court, the owners seemed to find a loophole. Real free agency wouldn’t arrive until 1993.

8

One player became synonymous with the term ‘free agent’ in the 1990s: Deion Sanders. He was an all-round athlete in the Jim Thorpe mold, lettering in baseball, football, and basketball at his high-school in Fort Myers, Florida. As a senior, Sanders was drafted by the Kansas City Royals, but he turned down professional baseball to play college football – alongside baseball and track – at Florida State University (FSU). The Seminoles, Bobby Bowden’s team, were emerging as one of the top teams in the country. Sanders had played quarterback and safety in high school, but FSU recruited him as a cornerback – a thankless position, designated to shut down wide receivers. But Sanders wasn’t about to be relegated, no matter what position he played. He showed out before long. As a true freshman, Sanders returned a punt and an interception for touchdowns. His sophomore year he upped that to four interceptions in eleven games played. He did the same his junior year. His senior year he had five interceptions, with one returned for a touchdown. He developed into a skilled route-jumper and shutdown corner. He could play man-to-man coverage against any team’s number-one receiver and give as good as he got. He was one of the most exciting kick returners ever to play the game. To see him run with the ball, it made you wonder why they didn’t just give him the ball every play. He was so fast – who could catch him?

Deion was never not about getting paid, and he knew where being humble got you. He had been overlooked before. FSU hadn’t wanted him at quarterback. They’d wanted him to play corner. They weren’t thinking about what he could earn in the NFL as a quarterback compared to as a corner. Cornerback was among the least financially lucrative positions in football. Sanders had seen the data and knew that it’d be a problem for him when (not if ) the NFL drafted him. So he came up with a solution to that problem, and that solution was a persona: Prime Time.

Prime Time – just Prime, to his friends – wasn’t exactly Deion Sanders. Unlike Deion Sanders, Prime was ostentatious. Prime was loud. Prime was flashy. Prime wore expensive clothes, expensive sunglasses, gold chains, Jheri curl. Prime said things like: ‘Water covers two-thirds of the Earth. I cover the rest.’ When it was pointed out that he neglected to do warm-up exercises, he came back with: ‘When have you seen a cheetah stretch before you go get the antelope?’ The point was to present success to attract success.

The idea was a winner. In the 1989 NFL draft, Sanders went number five overall to the Atlanta Falcons. But he wanted more money than they offered, more than twice as much as the cornerback picked fifth the year before. The difference between that cornerback and Sanders was that Sanders had a second pro sport he could fall back on. He’d been drafted by the New York Yankees in 1988 (how he’d got his gold-chain budget). The Yankees had taken an interest in Sanders’s speed, as they were looking for a leadoff hitter to take the place of Rickey Henderson, who’d stolen a hundred bases a year for them before they traded him to the Oakland Athletics. When the Falcons didn’t want to pay Prime what Prime thought Prime was worth, Prime could afford to sit out a year; Prime could do a lot worse than play outfield for the New York Yankees.

So Sanders held out. The Yankees had called him up from the minors in the summer of 1989. They saw an opportunity to give Deion a sample of what it was like playing in ‘the show’. They thought they might tempt him away from the NFL. Deion dutifully let the Falcons know about it. He held out until 7 September, when the Falcons agreed to terms. The way it played out, the Falcons didn’t look like idiots for paying Sanders more than twice what the fifth pick got paid the year before.

In Sanders’s first regular season game in the NFL, he returned a punt sixty-eight yards for a touchdown. Earlier that week he hit a home run in a game for the Yankees. Not even Jim Thorpe had ever hit an MLB home run and scored an NFL touchdown in the same week. Prime Time’s stock was going up.

Having secured his $4.4 million from the Falcons, he was less accommodating to the Yankees. He began negotiations for more money. He wanted $1 million a year, but the Yankees weren’t having that. Sanders was still growing as a hitter. Owner George Steinbrenner didn’t want to pay a major contract to a developing player. The Yankee front office worried that giving Sanders a high-dollar contract would sow division in the locker room. It’s likely that Sanders didn’t want to play for the Yankees anymore and was looking for an exit. He had probably known it wasn’t going to work out when he looked to see where he might land in the NFL draft, and saw the New York teams, the Jets and the Giants, were sitting on picks fourteen and eighteen respectively, neither pick anywhere near high enough to draft him. Like he told the Giants, he’d be gone by then.

9

The story went: Sanders had begged the Falcons organization to draft him. Which was odd, since the Falcons were in the conversation for the worst franchise in the NFL. They had one playoff win in their entire history, in the wild-card round. But the only teams with top-ten picks that shared a city with a Major League Baseball team were Detroit, Kansas City, Atlanta, and Pittsburgh – the number three, four, five, and seven picks, respectively. The Lions were going to pick Barry Sanders, a future Hall of Fame running back out of Oklahoma State. Kansas City was a non-starter because the Royals had drafted Sanders out of high school and he had blown them off to play football – not to mention Kansas City might be a little crowded for Sanders, what with another famous two-sport athlete there, Royals slugger and LA Raiders running back Bo Jackson.

Pittsburgh would’ve been the best NFL franchise Sanders could have landed with, at least in terms of a winning tradition. The Steelers had won more NFL championships than any other team in the Super Bowl era; but the problem with Prime Time going to Pittsburgh was the Pittsburgh Pirates weren’t in the market for an outfielder, as at the time they had as good an outfield as any ever: Barry Bonds, Bobby Bonilla, Moisés Alou. Atlanta was the only viable option Sanders had if he wanted to play football and baseball in the same city. Beyond that, the city of Atlanta had certain advantages. Atlanta’s baseball team, the Braves, were owned by Ted Turner, a billionaire back when that sort of thing was rare. Turner owned the Cable News Network, Turner Network Television, and Turner Broadcasting System – three national cable channels, one of which, TBS, televised every single Atlanta Braves regular season game coast to coast. The New York Yankees couldn’t even offer that. For a young Prime Time on the grind, trying to build his brand in professional sports, that kind of promotion was a gold mine.

10

Despite the individual success Sanders had on the field in 1989, the Falcons overall didn’t fare well, ending the year 3–13. Yet there were reasons to be optimistic. The team had a promising young quarterback, Chris Miller, and had traded a first-round pick in that year’s NFL draft to the Indianapolis Colts to get Miller some more help at the wide receiver position in the form of Andre Rison. He would complement wide receiver Michael Haynes. It was hard to imagine a defense being able to shut down both. The team had a new head coach, too: Jerry Glanville, who was hired by Atlanta a week after he was fired by Houston, where he’d had a controversial tenure as head coach of the Oilers.

Glanville was a man accustomed to getting death threats. On occasion, he would wear a bulletproof vest on the sidelines. They said if you saw him with his high-plains-drifter jacket on it meant he had the vest strapped on him underneath. All that was well and fine, but where things had really gone wrong in Houston was his lack of concern about the extenuating consequences of his feuding. Houston’s franchise quarterback Warren Moon took issue with Glanville putting a target on his players. Glanville talked tough but he didn’t have to walk the walk on the field, was the jist of Moon’s complaint. Humbled and perhaps more self-aware, Glanville came to Atlanta. He asked the team’s ownership to change the players’ uniforms. Like Prime Time, Jerry Glanville had his own persona – ‘the man in black’ – and he wanted his team’s uniforms to fit the persona. He had tried to get the Oilers to change their uniforms to all black, but the ownership had rejected the idea. He had better luck in Atlanta. Regardless of his poor playoff record, he had won twice as many playoff games as the team had in its entire history. So they humored him.

Glanville and Sanders seemed an ideal match. Sanders was never a cheap-shot artist or a dirty player, but both men were believers in the power of aura. With longtime head coach Marion Campbell gone, there was a chance for Sanders to assert his own aura in the locker room. Glanville, a fan of hype, was a fan of Deion and recognized the value he brought to the team, not just as a player but as a leader. After a lackluster first year, the Falcons began to find a winning formula.

These were Sanders’s halcyon days. He loved Atlanta, and the feeling was mostly mutual. He signed with the Atlanta Braves and, that summer, helped them to go from worst to first in the National League, when he filled in for Braves center fielder Otis Nixon, during Nixon’s suspension for drug use. And in 1991, the Falcons began at last to put it together. They were ‘the rudest team in the NFL’. Glanville always wanted to be seen as running with the bad boys, and now he was.

Sanders developed a close relationship with recording artist MC Hammer, who was at the peak of his popularity. In September 1991, Hammer released a new single ‘2 Legit 2 Quit’ – a song he recorded in honor of Prime Time and the Atlanta Falcons. The single sold five million copies and became the Falcons’ team anthem that year. Hammer was Sanders’s guest on the sidelines at every game, an unofficial member of the team. Glanville and Sanders, whether they admitted to one another or not, subscribed to very similar philosophies: hype was a tool you could use. Sanders famously distilled his motto in the lines: ‘If you look good you play good. If you play good you get paid good.’

When Sanders became Prime Time, he was taking a great risk. If he hadn’t delivered on the field, he would’ve looked ridiculous. To talk noise like Prime talked noise and then fail to show up for the game – death might be preferable to such humiliation. When you said so loudly that you were the best, that you were worth the top dollar, then not just every game but every play became important, because you could never slip, you always had to back it up. Every game was a championship game when you were telling everybody you were the champ. When you do that, though, there is always a chance you’ll fall flat. You’ll burn out. This was the fate of the Atlanta Falcons of the early 1990s. And it was almost the fate of Deion Sanders.

11

The high-water mark came in the wild-card round of the 1991 playoffs, when the Falcons went to the Superdome in New Orleans and disrespected their rival, the Saints, beating them 27–20. The Falcons were riding high. They were the hottest team in the league, having won five of their last six games (they’d won four of their last five in the regular season to finish at a worthy 10–6). VIPs milled around their sidelines: Hammer, Evander Holyfield, Travis Tritt (the country-music star was Glanville’s buddy), even James Brown. The only problem was the team as a whole wasn’t that solid. They had good players: Sanders, Miller, Rison, Jessie Tuggle, to name a few. But they hadn’t had time to build depth around their core, not enough to compete with the top teams in the NFL. There wasn’t a lot of playoff experience in the locker room. Too much of the focus had been on what was going right, on Sanders and Rison, former college rivals, now best friends – Prime Time and Showtime.

But the Falcons couldn’t stop the run. And then Glanville benched the team’s leading rusher, running back Mike Rozier, for the divisional round of the playoffs. Rozier had missed the flight to Washington, and then missed the 10 p.m. bed check at the team’s hotel the night before the game. Rozier had followed Glanville from Houston to Atlanta, and Glanville repaid his loyalty by taking him out of the game, even though he was the most productive running back that Glanville had and the conditions (monsoon) were not favorable to the passing game. The Falcons were unable to run the ball, allowing the ten-point favorites of Washington to sit back and watch the Falcons’ wideouts struggle for purchase in the deluge pouring into RFK stadium.

A divisional playoff loss on the road in Washington to the team that ended up winning the Super Bowl – this wasn’t the end of the world. But things began to fall apart, both for the team and for Deion. There were players who blamed Glanville for their humiliation. They thought Glanville should’ve been a grown-up about it and played Rozier. Rozier may have fucked up, but the playoffs were the playoffs. Glanville could’ve suspended him later. He picked a bad time to start looking down on bad-boy behavior. Wasn’t he supposed to be a party guy?

Deion went about his business. The dream would last a bit longer, but the events that would bring it to an end were already in motion. Tensions were growing between the Falcons and the Braves over who had Sanders’s ultimate loyalty. Football was Sanders’s wife; baseball, his girlfriend. But the Braves had made it to the World Series, whereas the Falcons was a team that had been beat down in the mud in front of their celebrity entourage.

It was one of the most brutal eras of NFL football. Teams were playing on Astroturf, which was the same as playing on concrete, only with concrete the abrasions one got wouldn’t be as bad. Players were getting carted off every weekend, never to return to the field. Helmet-to-helmet hits were SOP. Guys were still looking to knock people out. The Atlanta Braves were wary of investing too heavily in a player who might be incapacitated in the off-season. But when they looked at Sanders they saw Rickey Henderson with better power, not to mention that Sanders was good for the bottom line. He was a publicity factory. People would come just to see him play. Meanwhile, the lines began to blur for Sanders. He had been around long enough not to be overawed or deferential. He had been careful in the beginning, code-switching between the baseball world and the football world. Prime didn’t play baseball. Deion Sanders played baseball. But the more his celebrity grew, the harder it was to separate Prime from the baseball diamond.

Some of it was miscommunication, willful or otherwise. Sanders was getting playing time with the Braves, and he was performing well. He was showing signs of coming into his own as a hitter. Defensively, he was a solid outfielder. What he lacked in experience (like, say, how well he could read the ball coming off of the bat), he made up for in natural ability, and he could steal bases. If he got on base at all it was like hitting a double. Even if he didn’t steal bases, just his presence on first base could throw a pitcher off.

Things began to come to a head in the summer of 1992, when the Falcons offered Deion an extra million dollars if he ditched the Braves early so he could be with the team at training camp. The offer made headlines, Deion turned it down, and the only thing that came of it was an increase in frustration for all parties involved. In baseball, bringing attention to success wasn’t always a good thing. To illustrate: while in football it was acceptable to celebrate a play – be it a touchdown, a quarterback sack, an interception – you wouldn’t get away with it in baseball. Say you hit a home run in a game, if the other team thought you’d stayed and watched the ball too long when it came off the bat, your next time at the plate the pitcher was going to throw the ball at you, hard, and maybe at your head. Baseball was a game of subtlety.

It hit the fan in October. Deion had agreed to terms with the Braves under which he would be available to play for them in the postseason, should they make it to the postseason, which they did. They ended up playing the Pirates, in Pittsburgh, for the National League pennant, the same weekend the Falcons were scheduled to play the Miami Dolphins in Miami. The Braves told him they expected him to stay with the team the whole time. Deion indicated he was going to play for both teams that weekend. The Braves disagreed with his interpretation of their agreement, namely his interpretation of the meaning of ‘full time’ – Prime Time took it to mean that it was like the meaning of full-time as in a full-time job, whereby you have to work when you’re scheduled to work, but that you’re not beholden to be any specific place when you aren’t working. By Sanders’s interpretation, it stood to reason that he could play for the Braves in Pittsburgh on Saturday night, catch a plane to Miami that night, play in the Falcons’ game that Sunday, then go straight to the airport and fly back to Pittsburgh for the Braves’ game that night. He could charter a jet. Nike would help him put it together. CBS was interested in tagging along for the ride. Deion thought he was doing good, like he was coming to somebody’s rescue. It all seemed entirely reasonable to him. When Sanders got back to Pittsburgh, he rolled in around game time. He suited up but he didn’t play. The Braves let him sit on the bench.

The Braves lost that night. But they won the series in seven games, and they advanced to their second World Series in two years. They couldn’t keep Deion out of the starting lineup. He led the team with eight hits. Most of the rest of the Braves didn’t show up. Which was ironic. They were there, but they weren’t there. Deion, on the other hand, was there, and even missed a Falcons game to be there. But it didn’t matter. The well was poisoned. The Braves’ owner John Schuerholz was a highly competent general manager, but also kind of a prick. How much of a prick? Schuerholz traded Sanders in about the coldest way possible – to the Cincinnati Reds. Which, if you knew anything about Major League Baseball, meant you were getting owned. The thing they said about the Reds’ owner Marge Schott was that she was a fan of Hitler, wore Nazi armbands when at home, and when at work, was said to drop the hard-r casually. And it got cold in Cincinnati. Not Cleveland cold, not Green Bay cold. But colder than Sanders would’ve liked. Deion was from Florida. And they already had a Sanders on the Reds. Reggie Sanders. Who was a great player. And probably he and Deion were friends. At least I always assumed they were. But damn.

Atlanta was Deion’s city. It was like if the Bulls traded Michael Jordan or the Lakers traded Magic Johnson or the Celtics traded Larry Bird. It was like if the Bears traded Walter Payton. Granted, Deion wasn’t as vital to the Braves as any of those were to the above. But to the city, a city that had national aspirations, as in being a city that somebody not from there might give a fuck about, Deion Sanders was vital.

The Falcons flaked on him, too. They’d been winning in 1991. In 1992 they weren’t winning anymore. Chris Miller went down with a season-ending injury and needed knee surgery. Deion missed games. The offense struggled. The defense couldn’t stop the run. Glanville was looking bad, and like anybody else would, Jerry Glanville blamed people around him for fucking up his shit. Deion was not immune. He was no longer the heart and soul of the Atlanta roster. He was labeled a distraction, more trouble than he was worth. He wasn’t offered a new contract.

12

The dissolution of the Prime Time Falcons set Atlanta back years. Deion left for the San Francisco 49ers and you saw him trade blows with Andre Rison in the Georgia Dome in 1994, on TV. They both got fined $7,500. Deion and the Niners won the Super Bowl that year. Then Deion left for Dallas and won a Super Bowl for the Cowboys the season after that. He never played for Atlanta again. Atlanta still hasn’t won a Super Bowl. Deion retired in 2006.

In 2020 Deion Sanders made his foray into coaching college ball. It began at Jackson State University (JSU) after a ‘strategic call from God’. Clearly he wasn’t motivated by money. Sanders’s salary at JSU was $300,000 a year, a fraction of what he could’ve made as a TV analyst, and half of that salary he donated back to the school to put toward the renovation of its football stadium. Sanders coached three seasons at JSU. The first year the team went 4–3, in a season shortened by the 2020 pandemic. Sanders’s second year at JSU was a turn-around year for the program, with the JSU Tigers going 11–2 in 2021 and then 12–1 in 2022.

Two years ago, after another call from the Almighty, Sanders became head coach of one of the worst teams in one of the whitest college towns in America: the Buffaloes of Boulder, Colorado. CU Boulder was a football backwater when Coach Prime arrived. The last time the school won a national title was 1990. In 2022, Colorado won one game, losing eight and finishing dead last in their conference. The athletic director of the school, Rick George, couldn’t see a downside in taking a chance on Coach Prime.

It wasn’t much of a gamble. Sanders brought with him two of the best players in college football: his son, quarterback Shedeur Sanders, and wide receiver/defensive back Travis Hunter. They came to Colorado via the transfer from JSU. Despite winning four times as many games as the team did the year before, Sanders was, not surprisingly, criticized. It was said he wasn’t ‘really a head coach’, but more like a ‘producer’, someone who made things look good, but who wasn’t serious about winning. This only raised the question: what is the college coach’s priority: to win a championship or to try to get as many players as possible into the pros? You can’t eat a national championship trophy. When Travis Hunter was left off the list of candidates for the Jim Thorpe trophy, Deion promised to give him his own.

13

A football man is in the White House again. In 1984, Donald J. Trump became owner of the New Jersey Generals, a professional team in a then-newly-founded USFL, the United States Football League. By then, the New York property mogul and future POTUS had twice tried and failed to acquire an NFL team, the Baltimore Colts, in 1981 and 1983. He offered Colts owner Robert Irsay $50 million twice, and twice Irsay had turned him down. When he bought the New Jersey Generals, he inherited Herschel Walker, a Heisman Trophy-winning running back and second-year pro. He also inherited a team that played its games in the spring. Which Trump, as a sports fan, found sacrilegious. In his second year as owner he led a revolt of the USFL ownership, whom he convinced to go against the NFL head-on, to schedule their football games to be played in the fall like everybody else.

Of the league’s owners, Trump was the most active in the media, making his importance as an owner outsized. The other owners, in turn, followed him to the league’s destruction, all in what was no more than a ploy by Trump to coerce the NFL into a merger. Trump’s motive was not long in being laid bare. Trump enlisted attorney Roy Cohn to help bring a suit against the NFL, in the hopes that, on grounds the NFL had illegally colluded with the three major US TV networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) to freeze the USFL out of the national market, the US government would compel the NFL to merge with Trump’s USFL. Trump’s game was transparent, his tact so lacking that NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle vowed that as long as he lived Donald Trump would not own an NFL franchise, a vow that held good when Trump failed to acquire the Dallas Cowboys in 1988.

Pete Rozelle died in 1996. Trump made a bid in 2014 to buy the Buffalo Bills. It was a deal Trump couldn’t close. It’s been said he couldn’t come up with a sufficient line of credit. He was reported to have offered a billion. The team sold for $1.4 billion. Shut out again, Trump would have to settle for running for the highest office in the land, winning, against all odds, the 2016 US presidential election. The rest is well known.

Trump wasn’t done with football, though. He still likes to attend Southeastern Conference games. The crowds are well-disposed to him. And football remains the lifeblood of the Republican Party. From 2016 Republicans began to take issue with the fact that the NFL charged the military for ads. They don’t anymore. Flags. Blitz. CTE. Lockheed Martin. One and the same. Lights, camera, action.

It’s said the game’s not as violent as it used to be. If that’s true, it is for the best. The game is still violent enough. It’s violent enough and yet the rules let the quarterback live a little while longer, when the position used to be like a spot on death row. In other respects, things stayed the same. We still render to the dollar. Once more the season is over. It doesn’t matter who won the trophy or who the president is, the massacres will continue. We have lost count of how many we’ve committed since 9/11. If there’s a God in heaven, America will burn to the ground one day. Until then, there is football.

Jim Thorpe playing for the Canton Bulldogs, 1915-1920