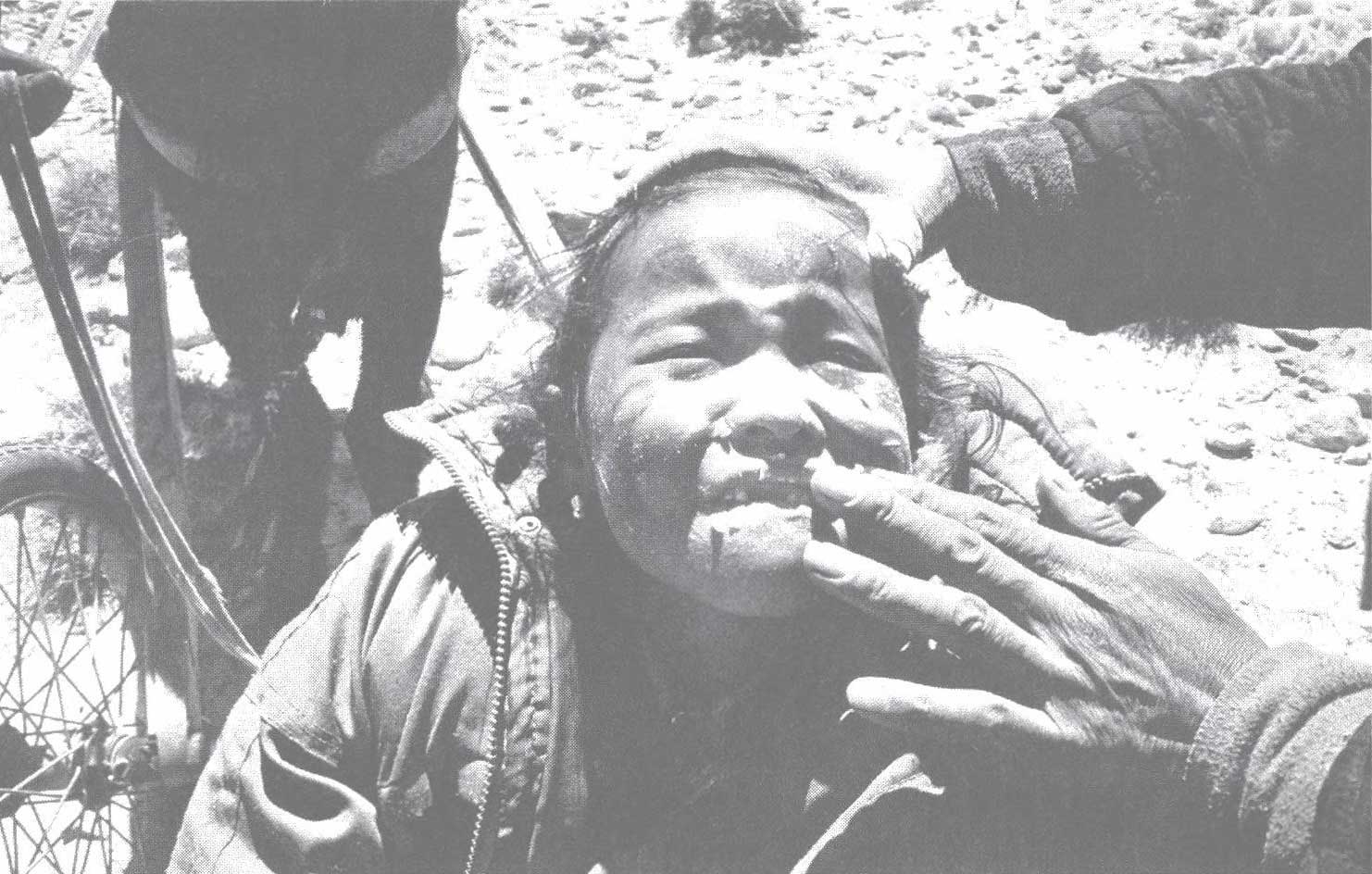

On 19 December 1996, Deyang, a thirteen-year-old Tibetan girl, whose name means ‘Melodious Happiness’, died from exposure while she was trying to cross the Himalayas to Nepal. It was her third attempt and the first time she had reached the border with Nepal. A week later, a thirteen-year-old Tibetan boy died of frostbite in hospital in Kathmandu, after making the same journey. In November 1998, Chinese police shot a fifteen-year-old Tibetan boy near the Nepalese border. He died in hospital from his wounds. All three had belonged to groups of Tibetan refugees attempting to escape Chinese rule at home and cross the border into Nepal.

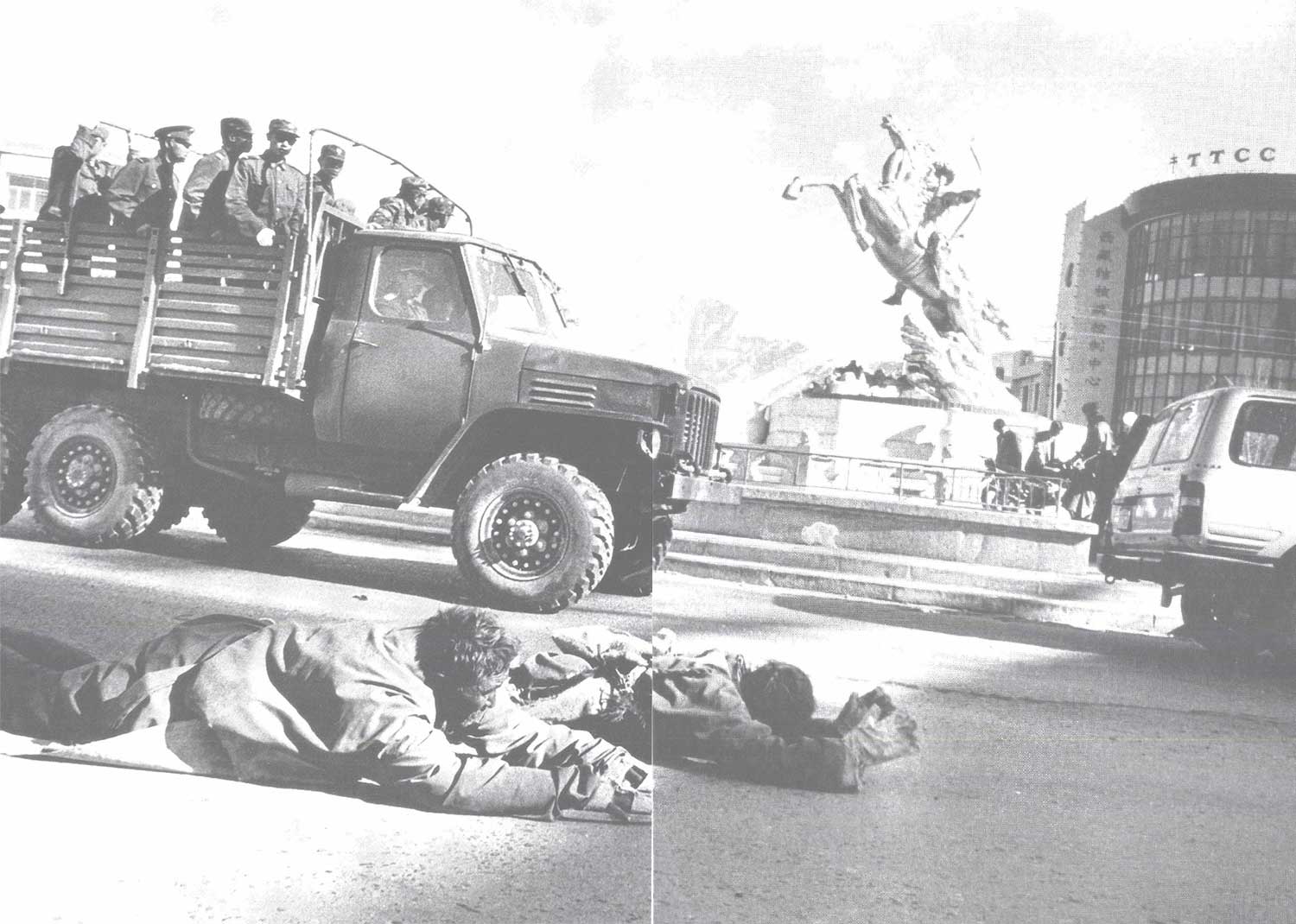

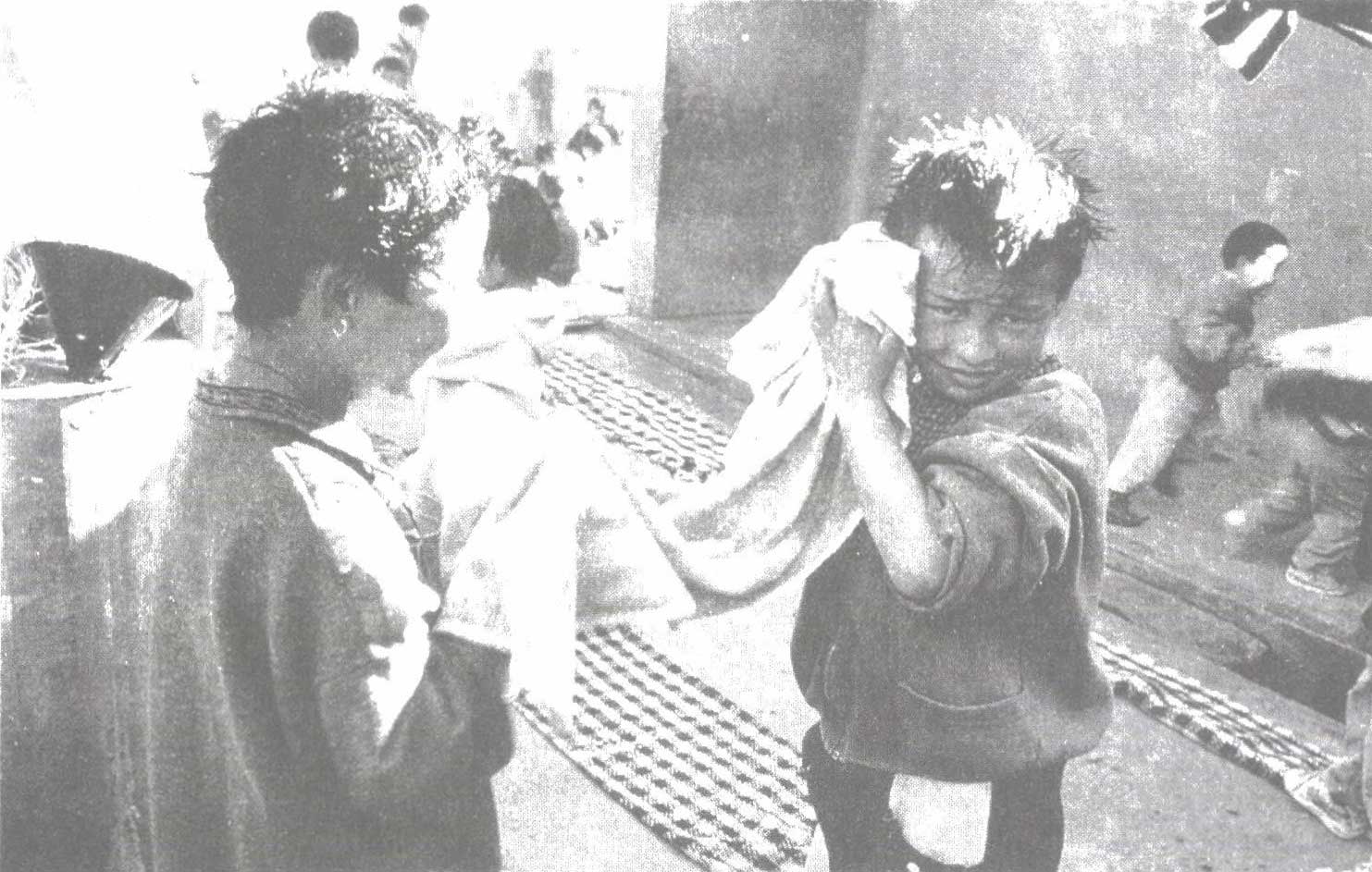

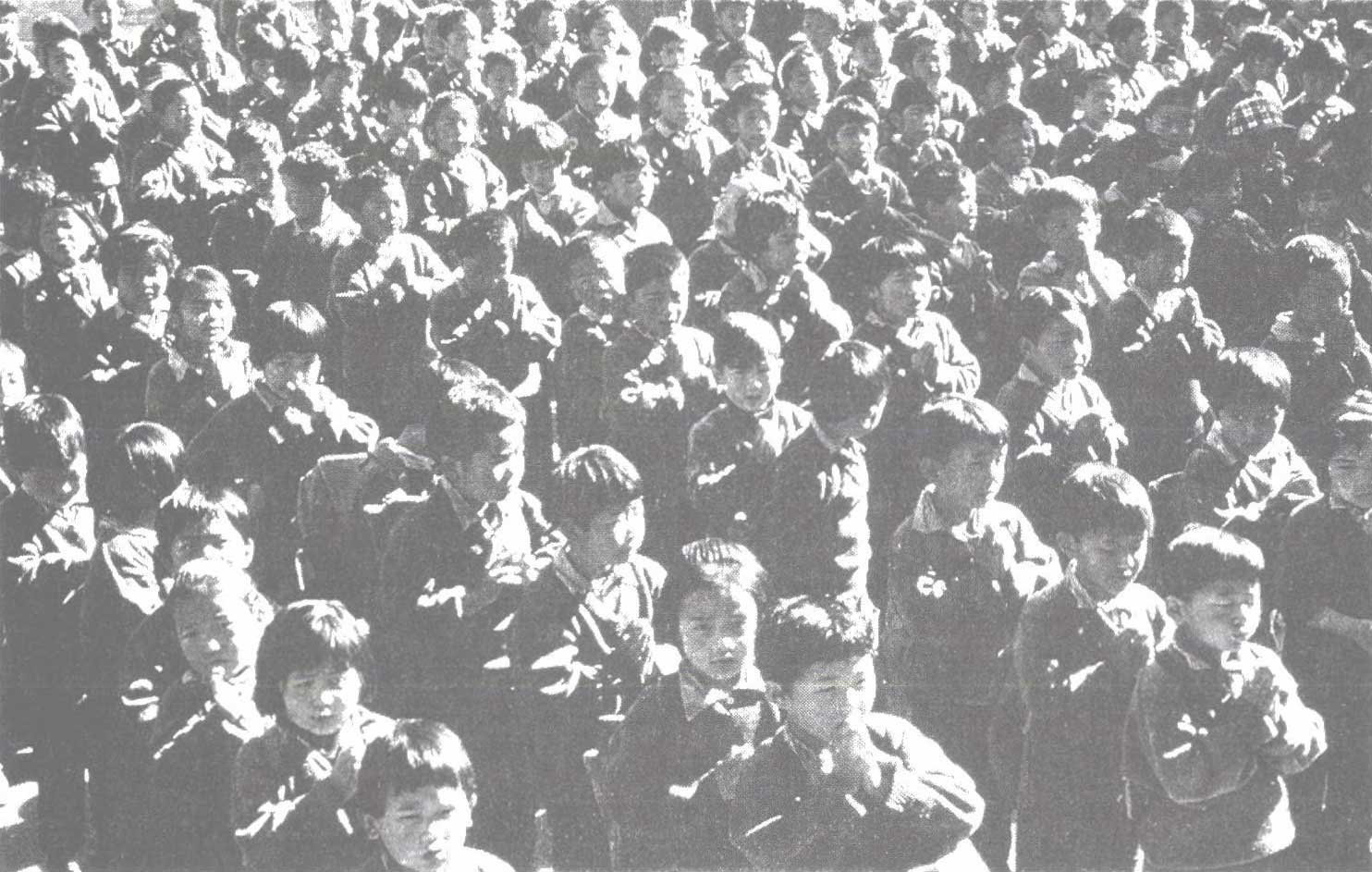

Every year, more than 2,000 Tibetan refugees arrive in Nepal and India seeking asylum. Almost fifty per cent of them are children. The majority are unaccompanied by their parents but trusted to guides and other refugees who it is hoped will deliver them into the care of the Tibetan authorities in exile. If they are caught by Chinese border patrols, they will be returned to Tibet where they run the risk of detention or imprisonment.

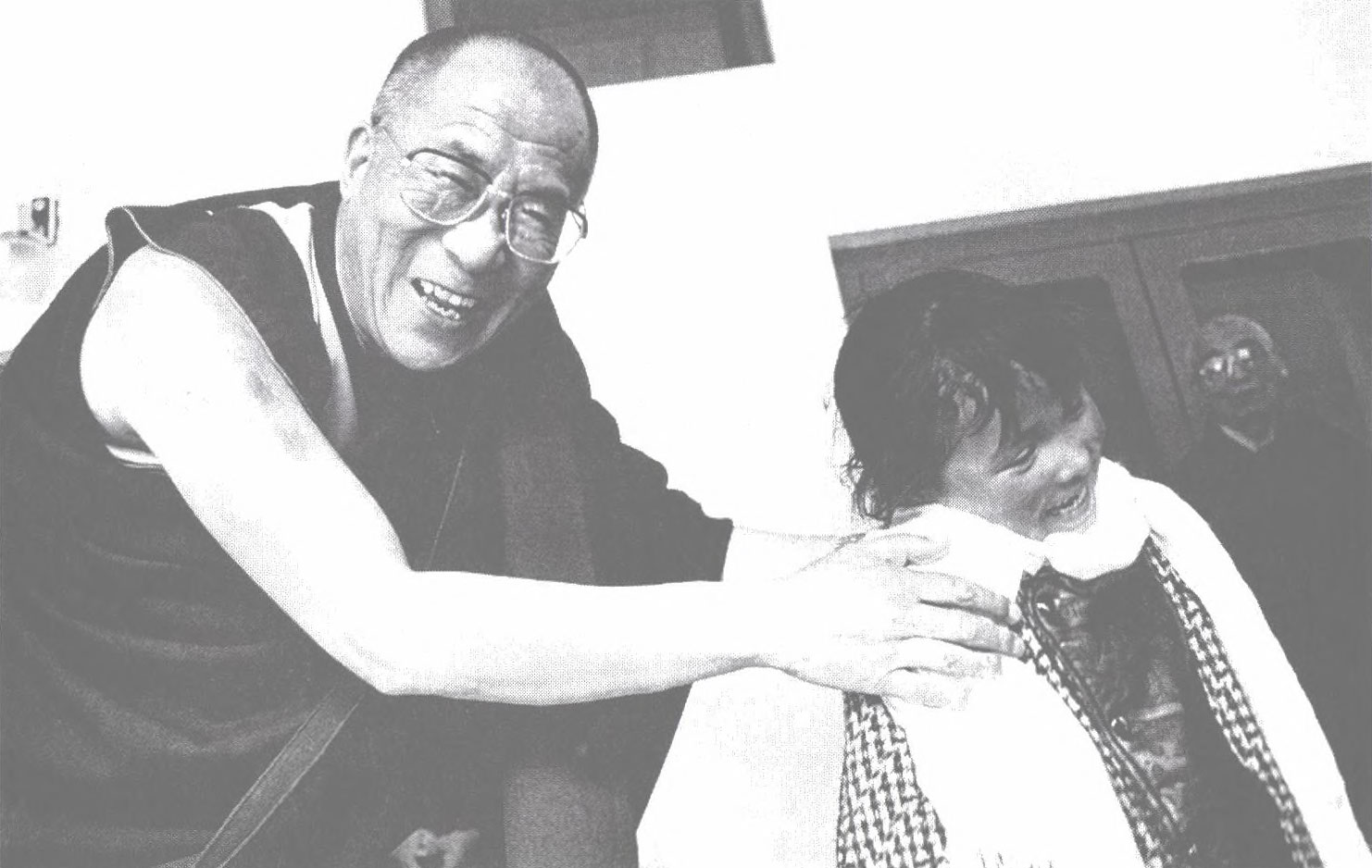

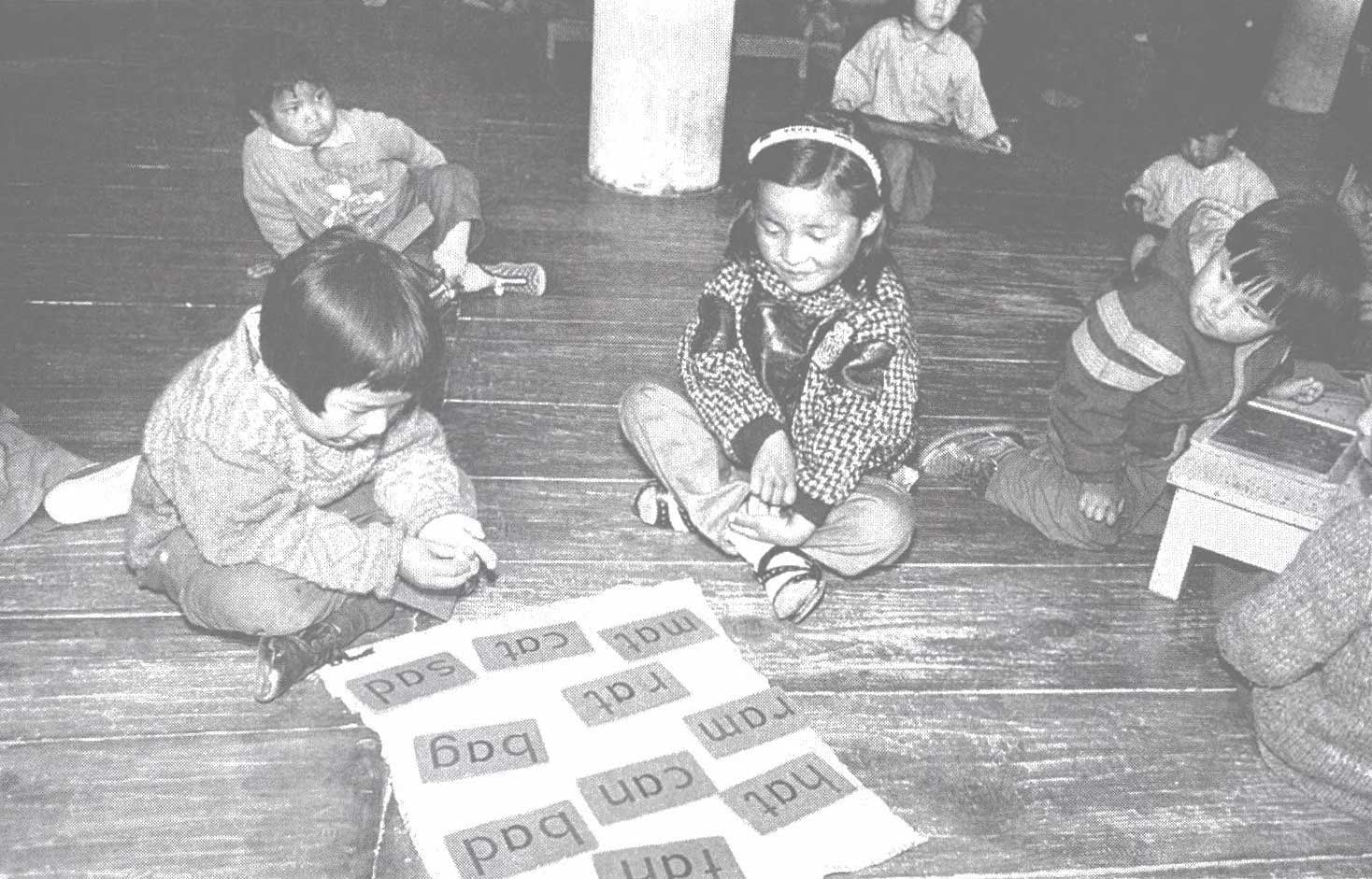

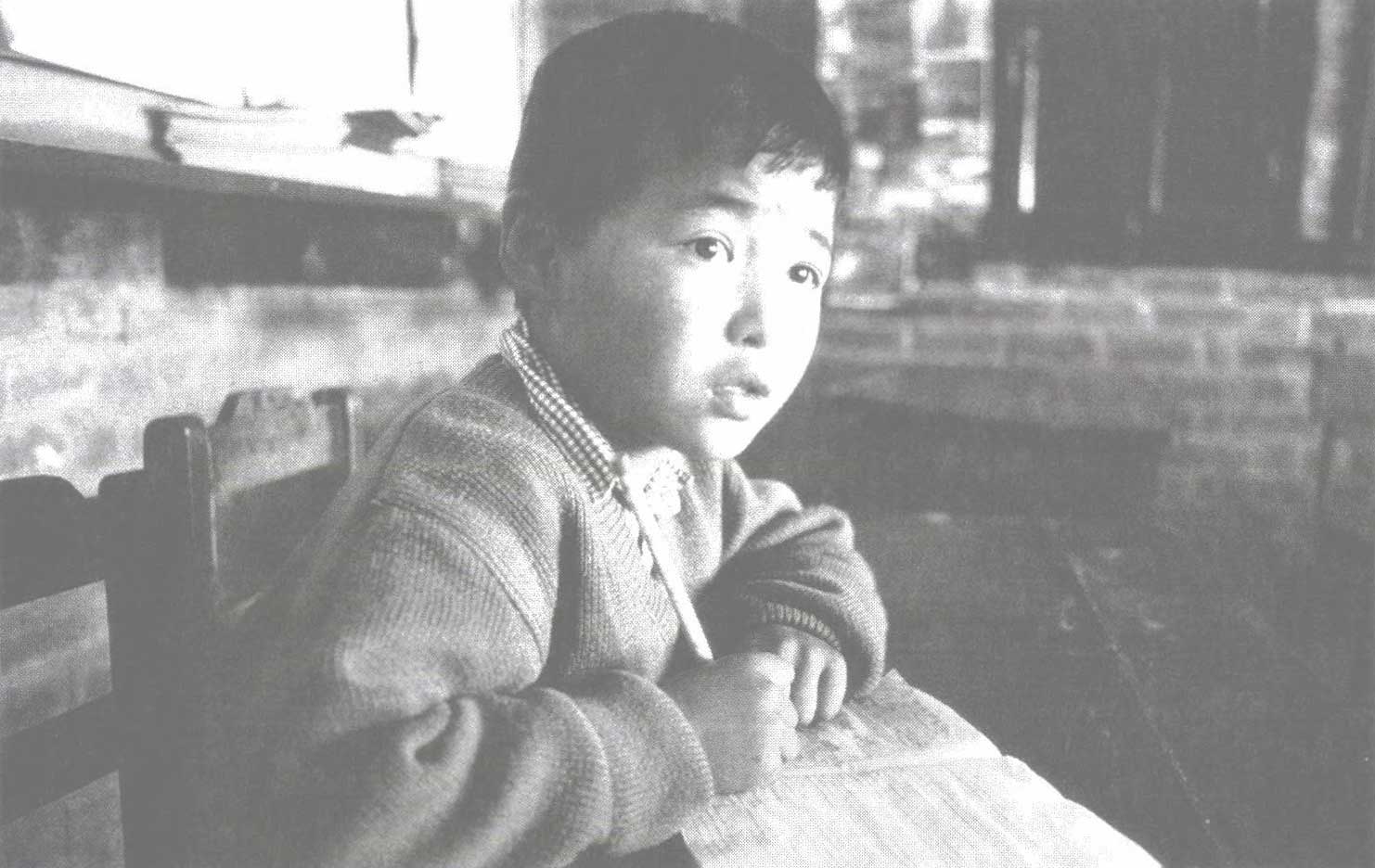

Thousands of children have left Tibet this way since the Chinese occupation in the 1950s. Once in India, many of them have been educated in one of the network of Tibetan schools where they can continue their traditional Tibetan schooling, which is restricted under the system of ‘patriotic education’ imposed on secondary schools throughout China and Tibet. The Tibetan nation in exile has its capital in Dharamsala, India, where the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, who made his own escape from Tibet in 1959, has his headquarters, and where his sister runs one of several schools for Tibetan children.

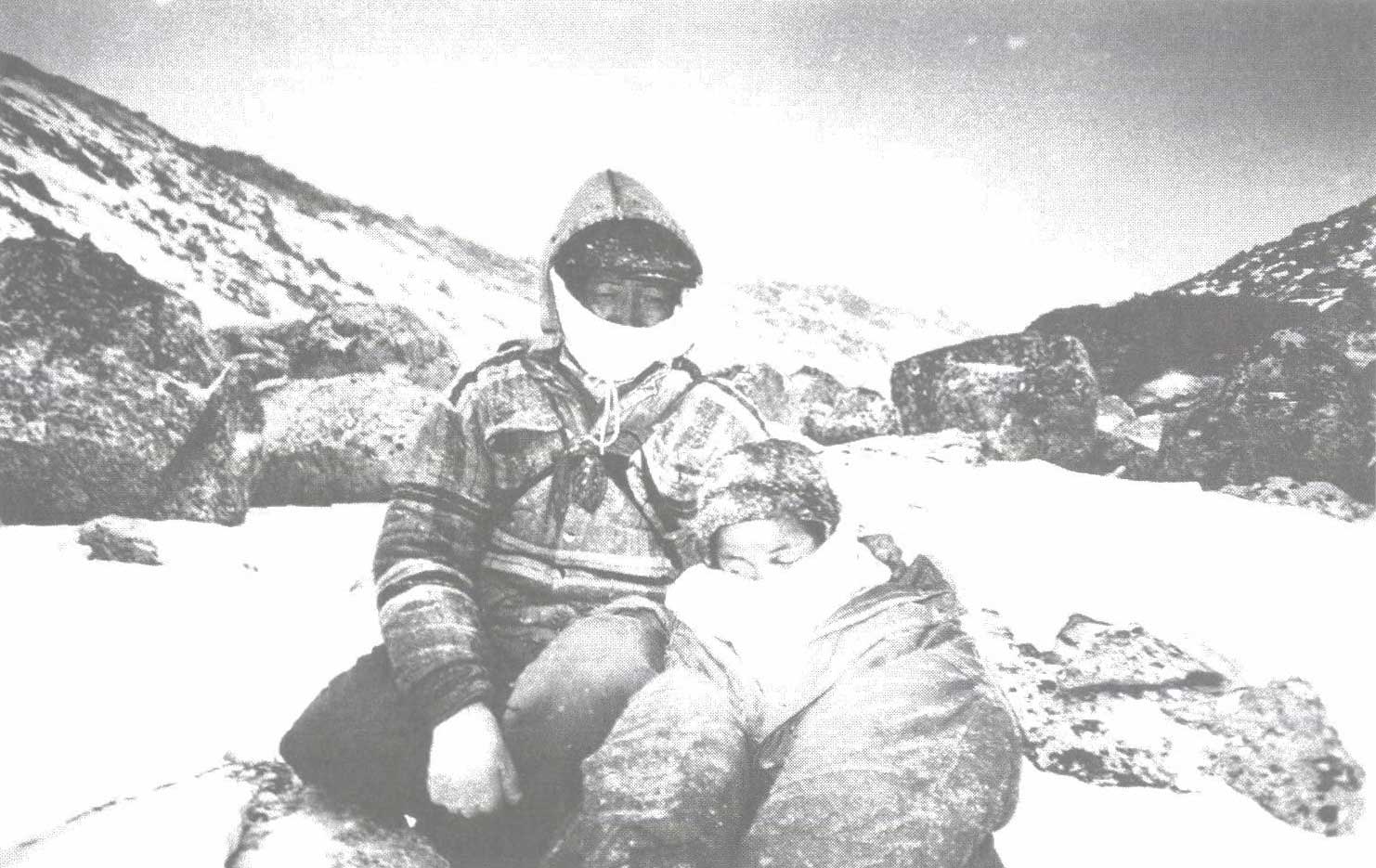

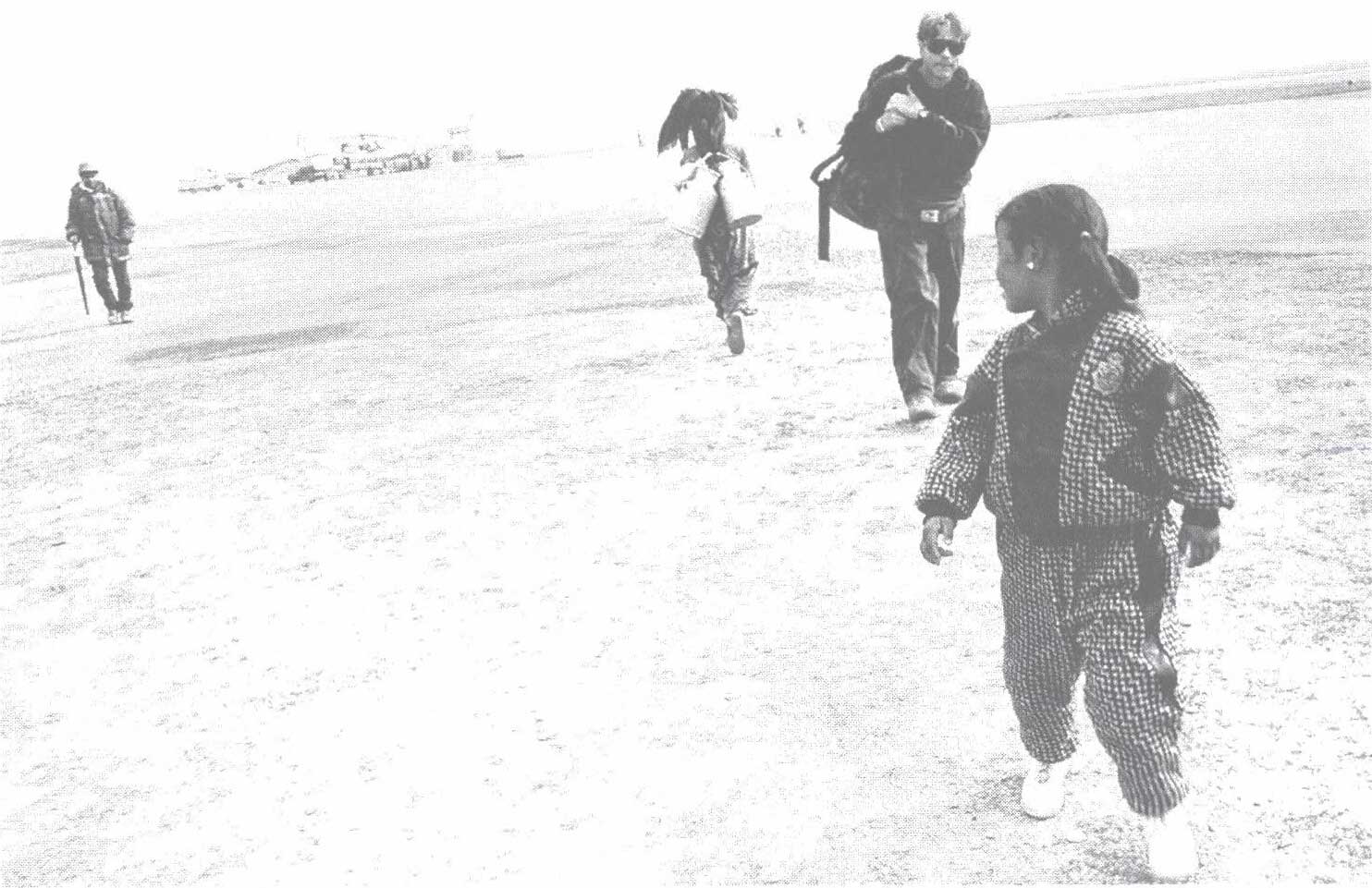

In 1995, the Swiss photographer Manuel Bauer made contact with a Tibetan who was planning to take his six-year-old daughter across the Himalayas on foot. He agreed to let Bauer, who is also a mountaineer, go with them. What follows are extracts from the diary he kept on the journey.

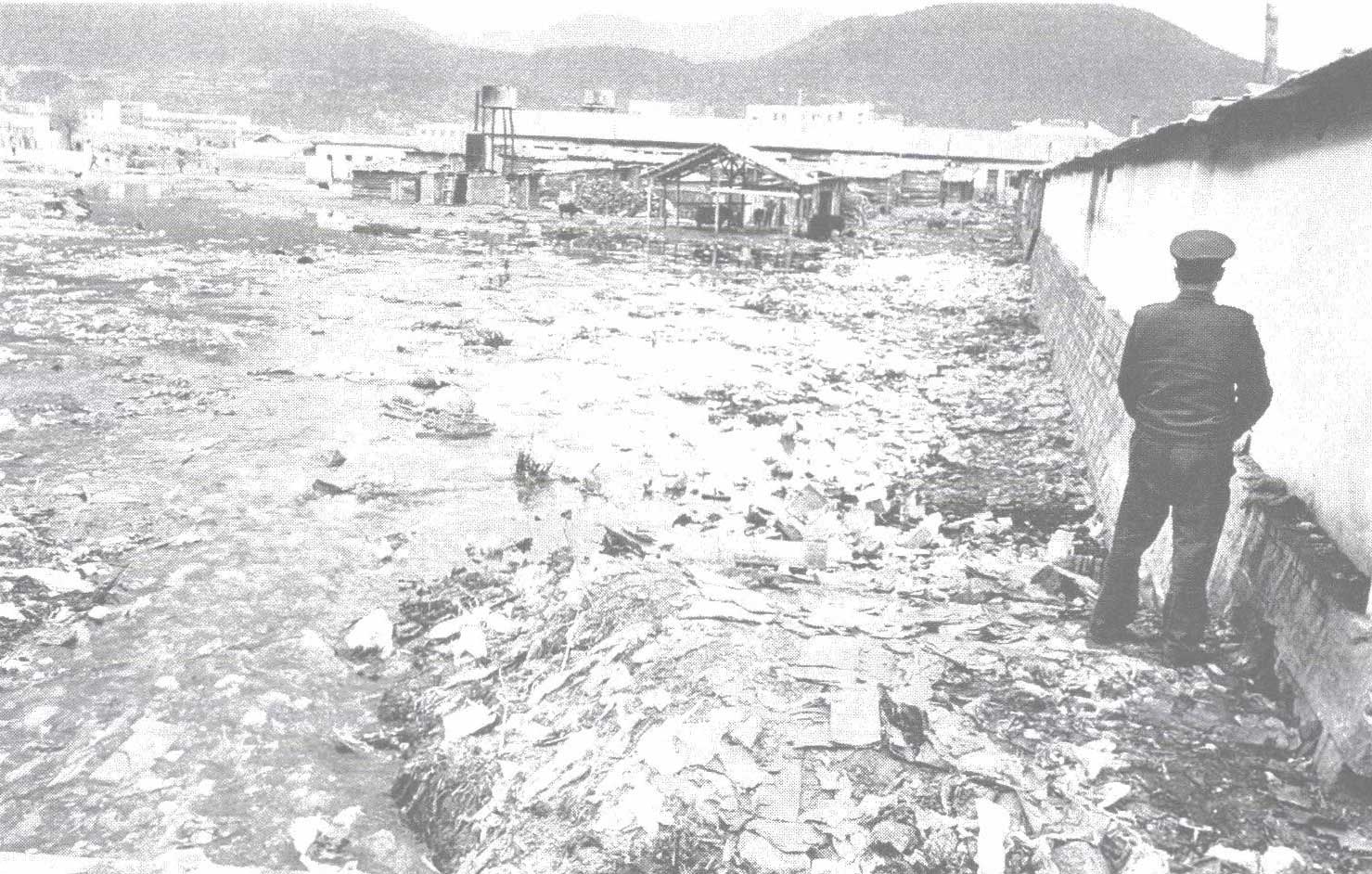

Day one: I am sitting in my hotel room in Lhasa having just come back from Bayi, a major Han Chinese military base in central Tibet. ‘Bayi’ stands for August 1, the day the People’s Liberation Army was founded in 1927. In that sprawling concrete city it was all too clear how hopeless it is for Tibetans to retain their cultural identity inside their own country. In Lhasa the Chinese are clearly favoured with better schools and housing and higher incomes.

Day three: I have been put in contact with a Tibetan who plans to escort his daughter into exile in India. My idea, which I’ve carried around with me for five years now, is finally coming to life.

Day four: I had my first meeting with Kelsang at one of the Chinese shopping centres in Lhasa. He was looking for shoes for the trip. It’s important to have strong footwear in order to avoid frostbite and possibly having your feet amputated at the end of the journey. He rejected a sturdy looking pair of boots which turned out to have cardboard soles, and bought two pairs of sneakers, which are lightweight and reasonably durable.

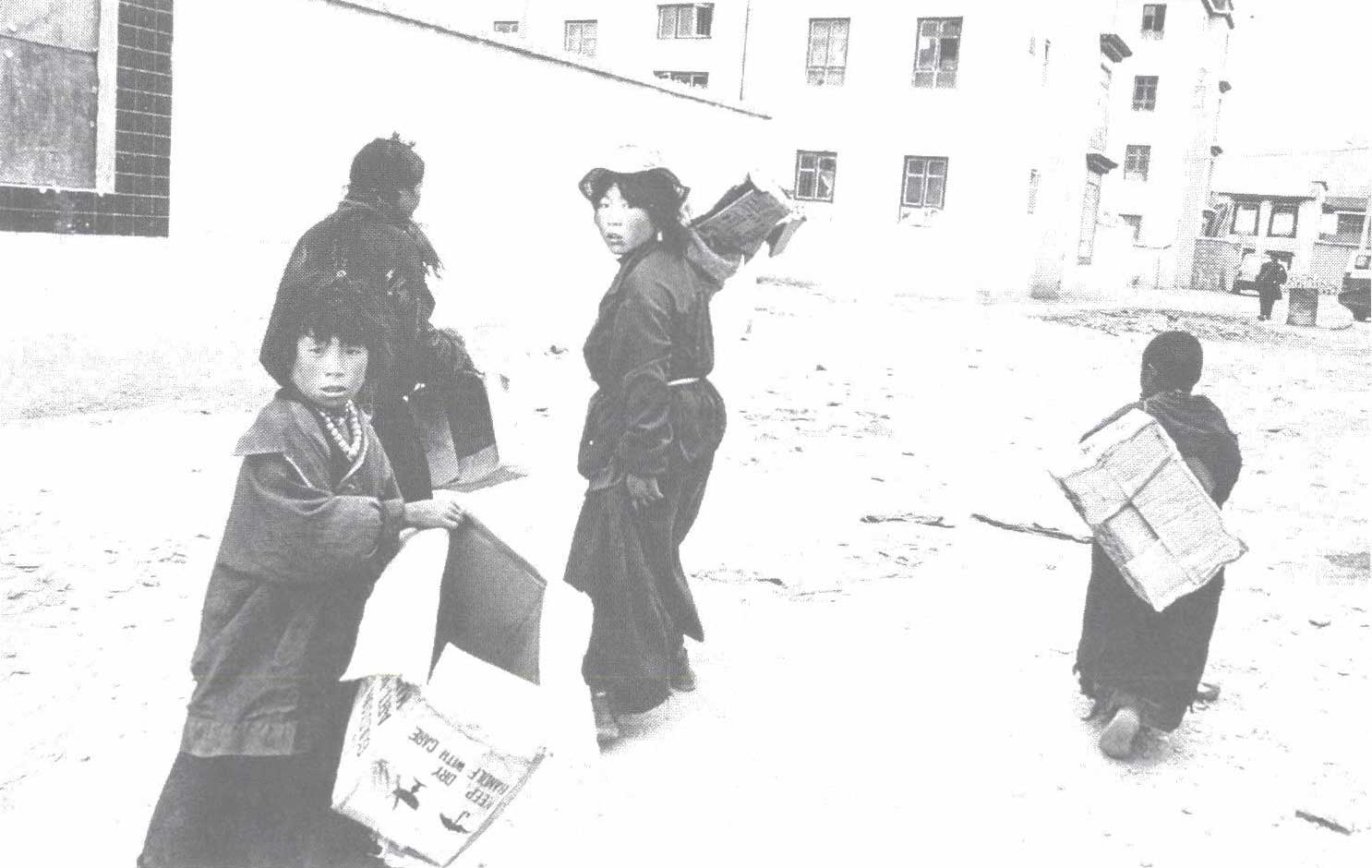

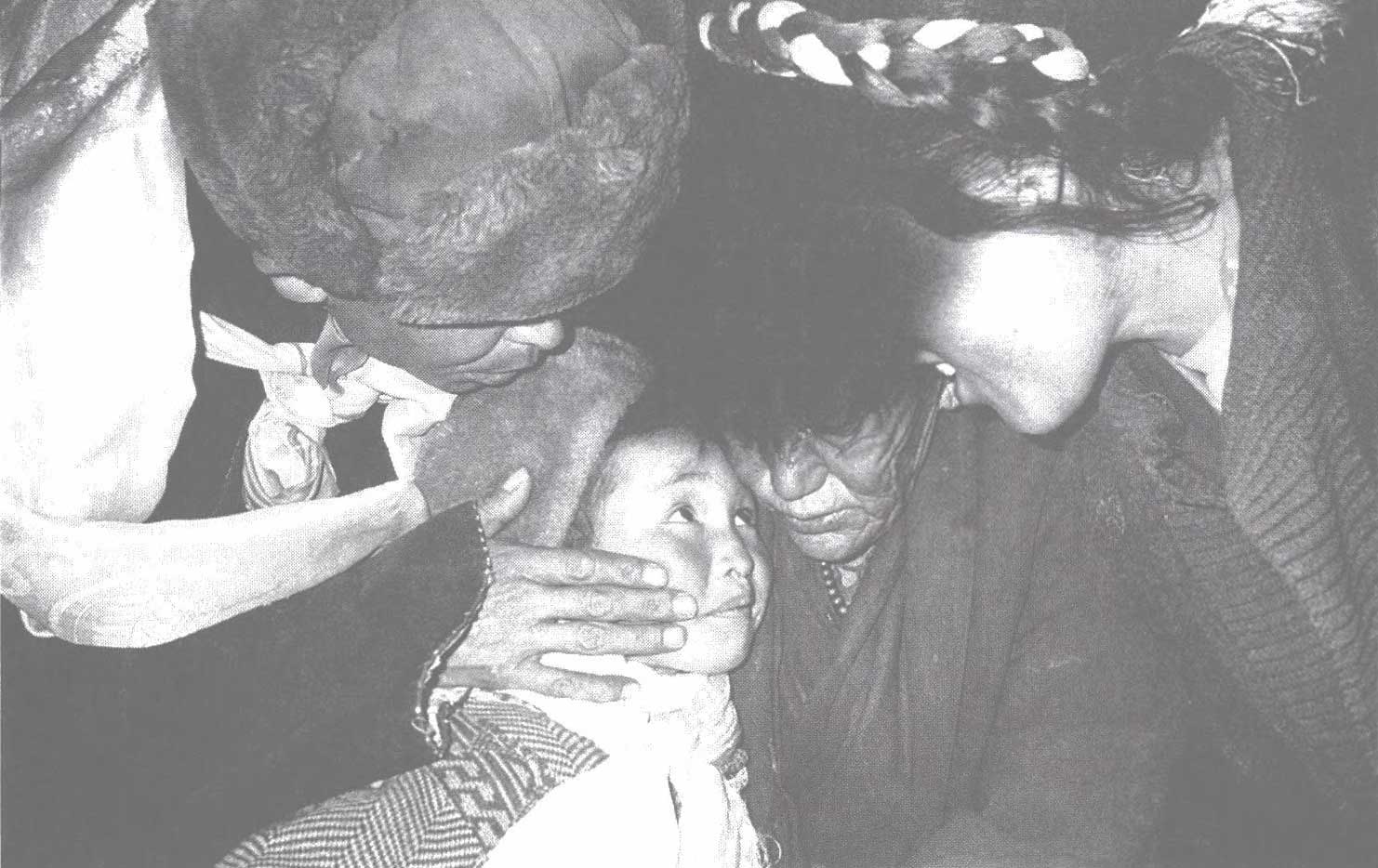

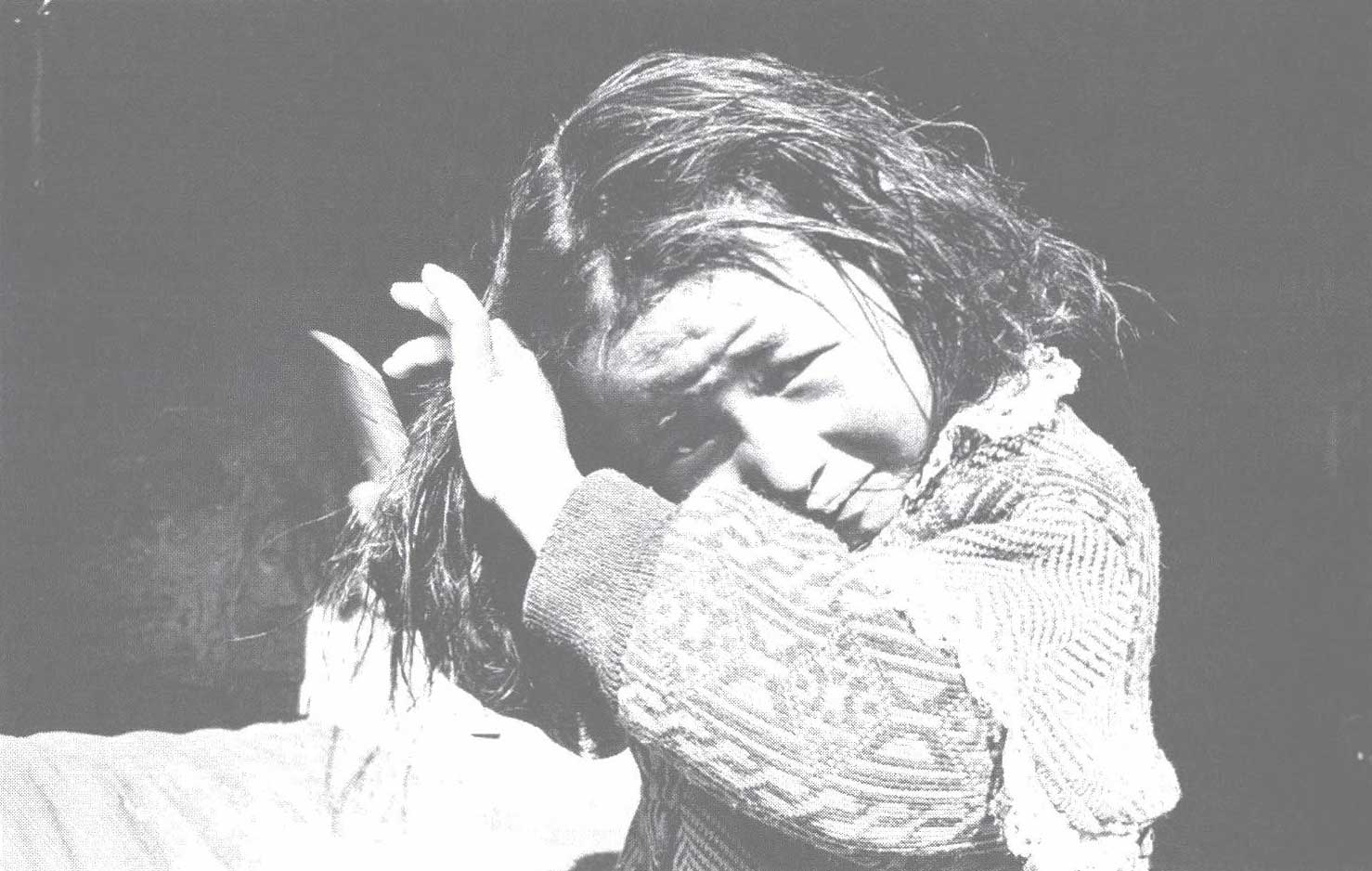

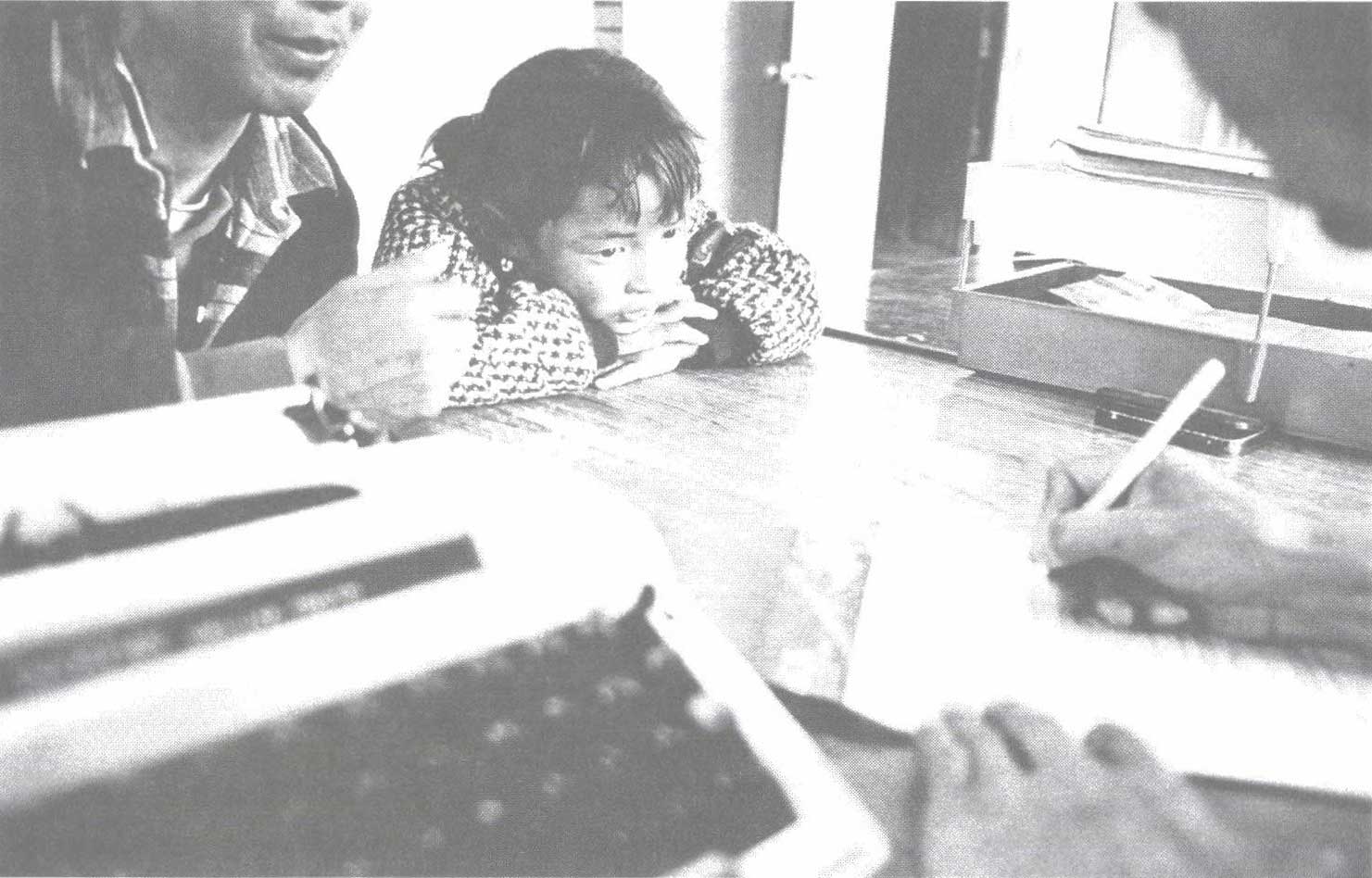

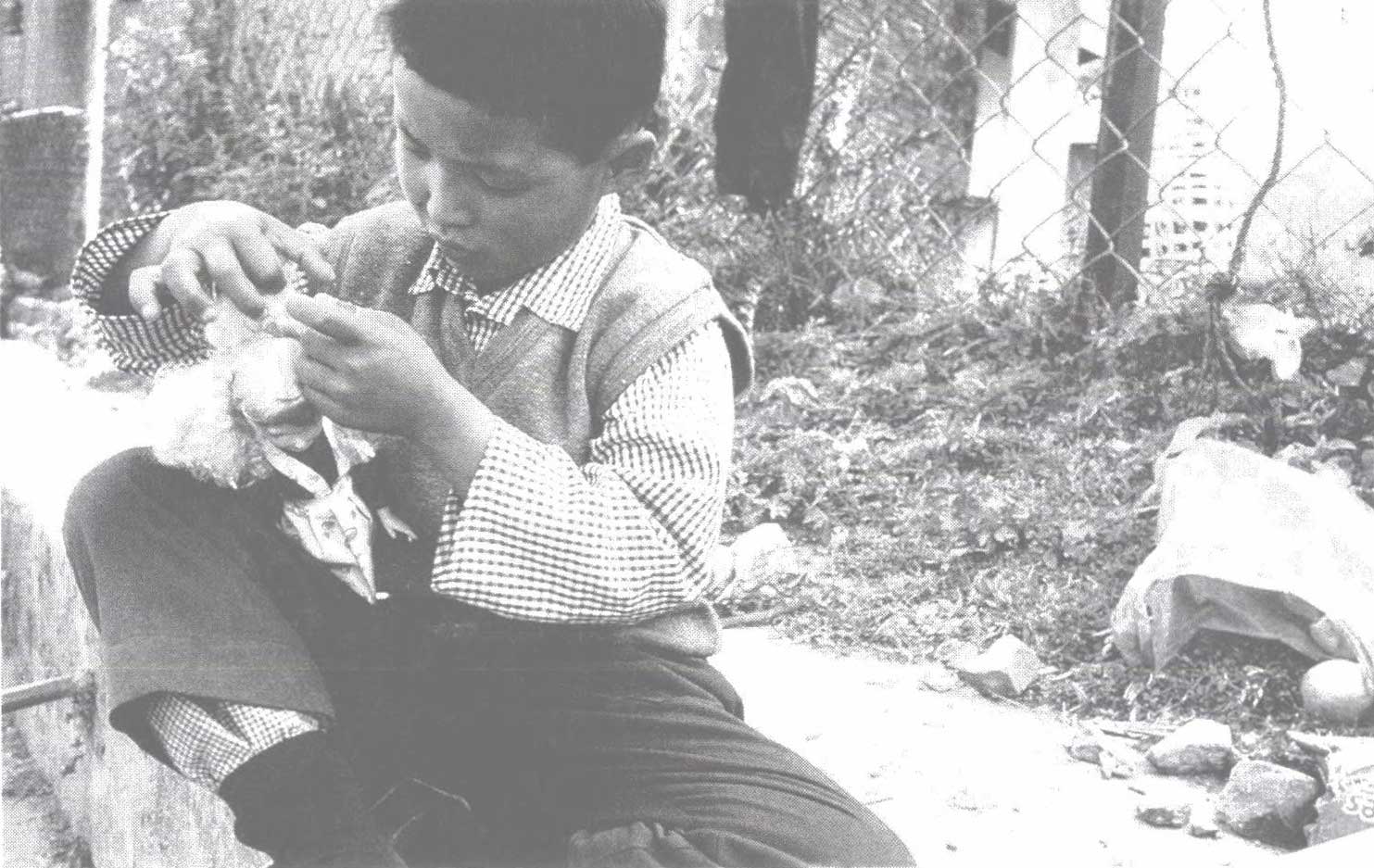

Day seven: Kelsang took me to meet his family in the old part of the city. We went at night. The streets were empty. The clocks in Lhasa are adjusted to Chinese time and the Chinese go to bed early. His wife and mother welcomed me with some suspicion. A small girl came into the room carrying a tray with cups of butter tea. This was Yangdol. I wondered if she had any idea what was in store for her. With gestures her parents explained to me that they were putting all their hopes on the little girl to continue their traditions outside Tibet.

Day nine: I have adopted the guise of an antiques dealer. Kelsang is a carpenter and this way my visits to him won’t arouse suspicion. The Chinese don’t want negative press from inside Tibet, so contact with foreigners is heavily restricted. Late this evening, Kelsang knocked on my door. He was a bit tipsy. He had persuaded a higher official to issue him and his daughter with a travel permit for a pilgrimage to Lake Manasarovar. It took him quite a lot of drinking and some extra money, but it worked. I got myself a permit for the road to Kathmandu, which should cover the first part of the trip.

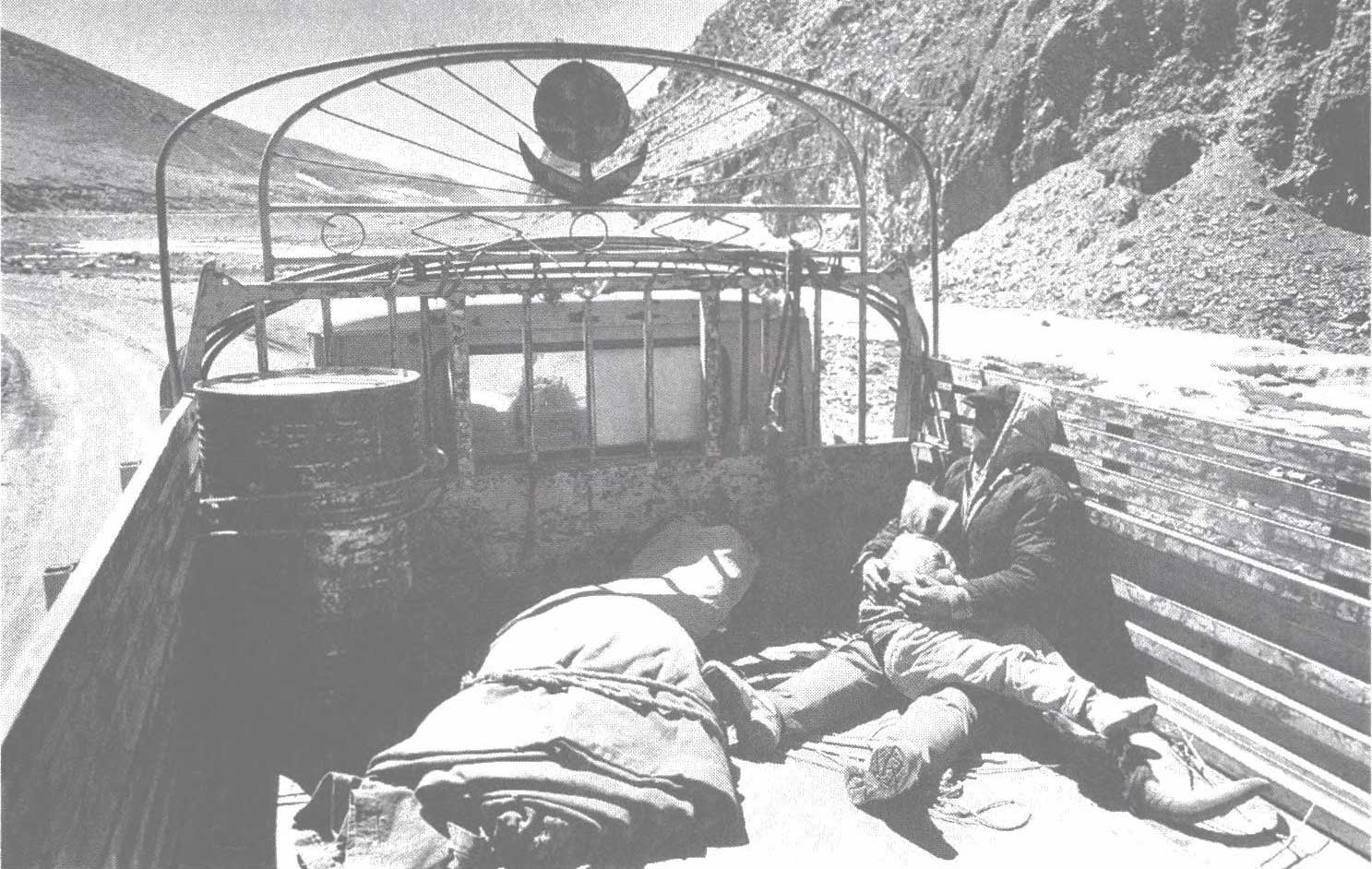

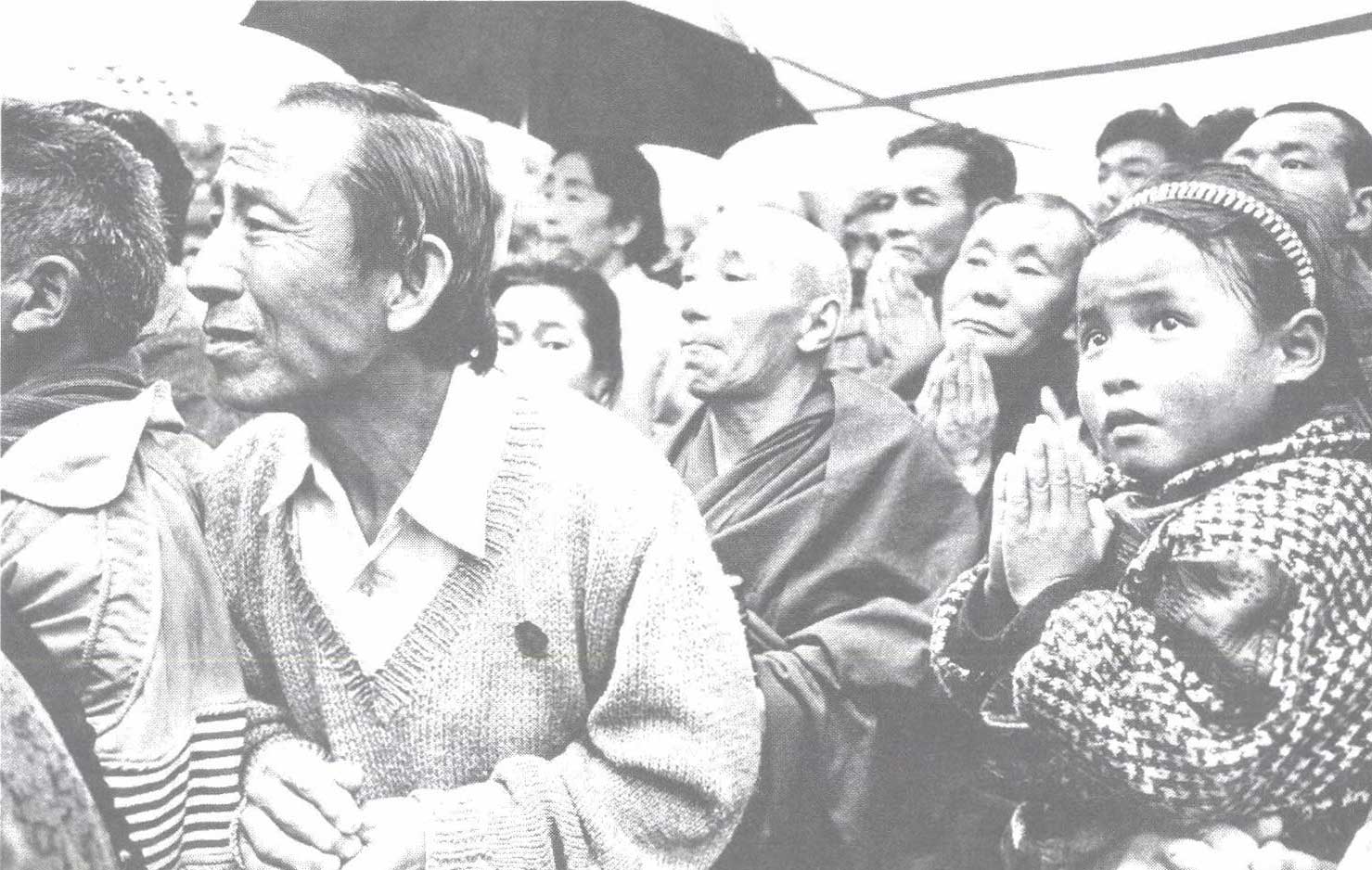

Day ten: We left Lhasa this morning on the back of a truck. At nightfall, at our first stop, we were told we would have to wait for a few days because of bad weather. This year the snowy season extended a long way into spring. Yangdol and Kelsang used the time to pray for the success of their journey at a nearby monastery. I decided to prepare myself by climbing the surrounding hills. I watched vultures circling a Tibetan burial ground. The Tibetans cut their dead into pieces and leave them out in the open air, so the body can complete the cycle of life in harmony with the laws of nature.

Day fifteen: My only contact with Kelsang for the last couple of days has been signs in the dust on the side of the hotel telling me each time the trip has been postponed for another day. The clerks at the hotel are getting suspicious about me.

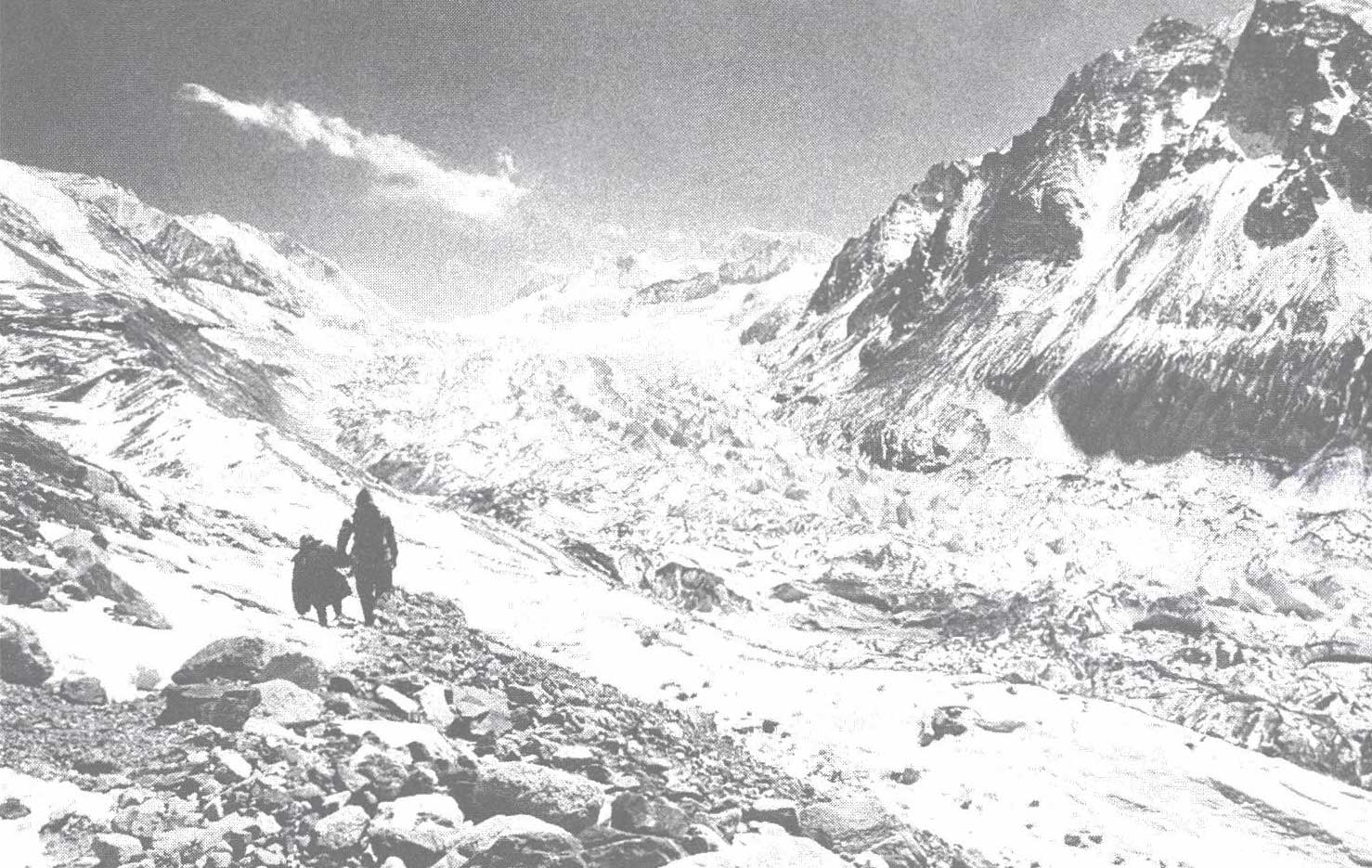

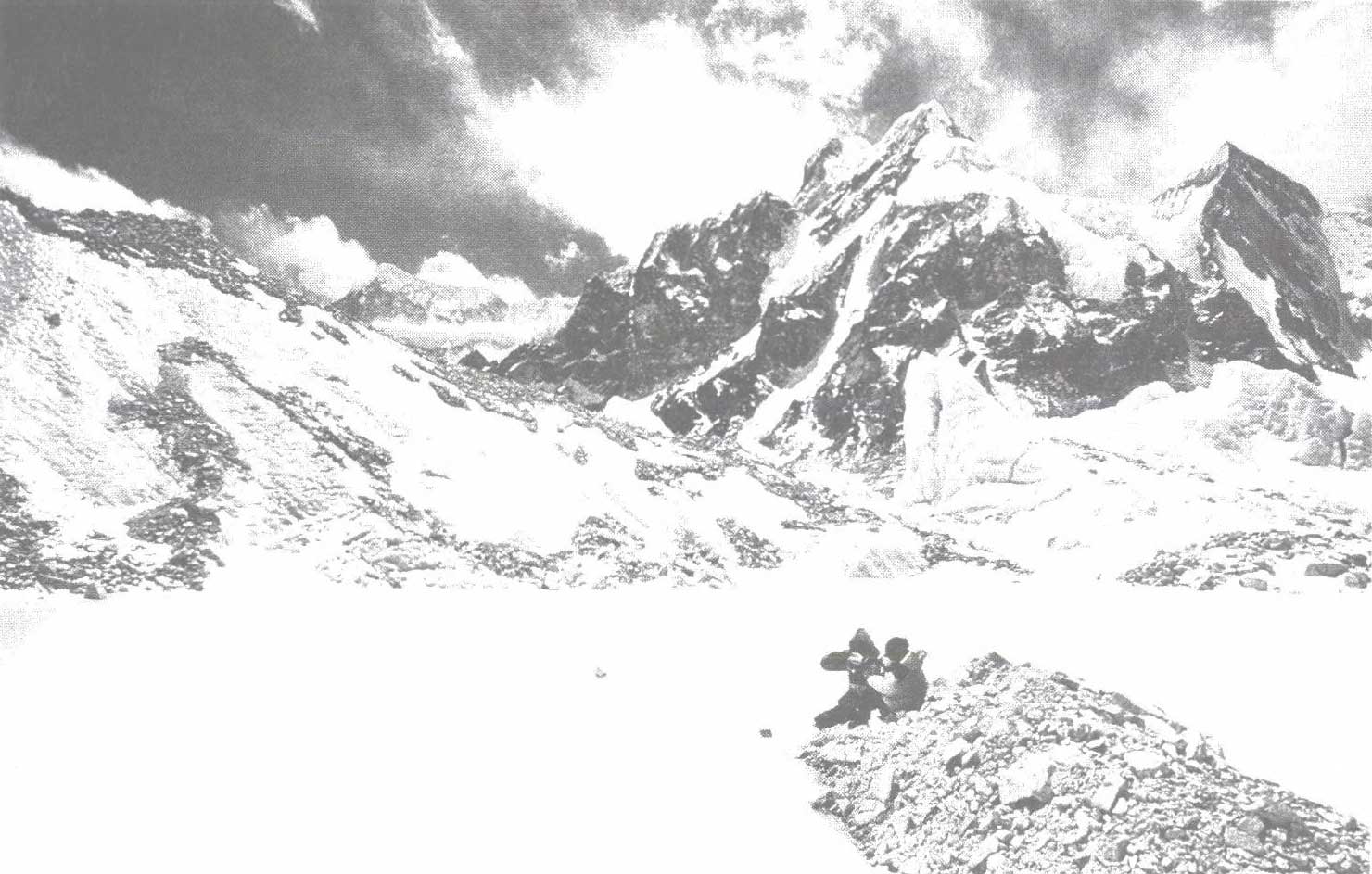

Day seventeen: We finally set off again by truck and reached the foot of the Himalayas. We can see Everest and Cho Oyu, both over 8,000 metres, high in the distance.

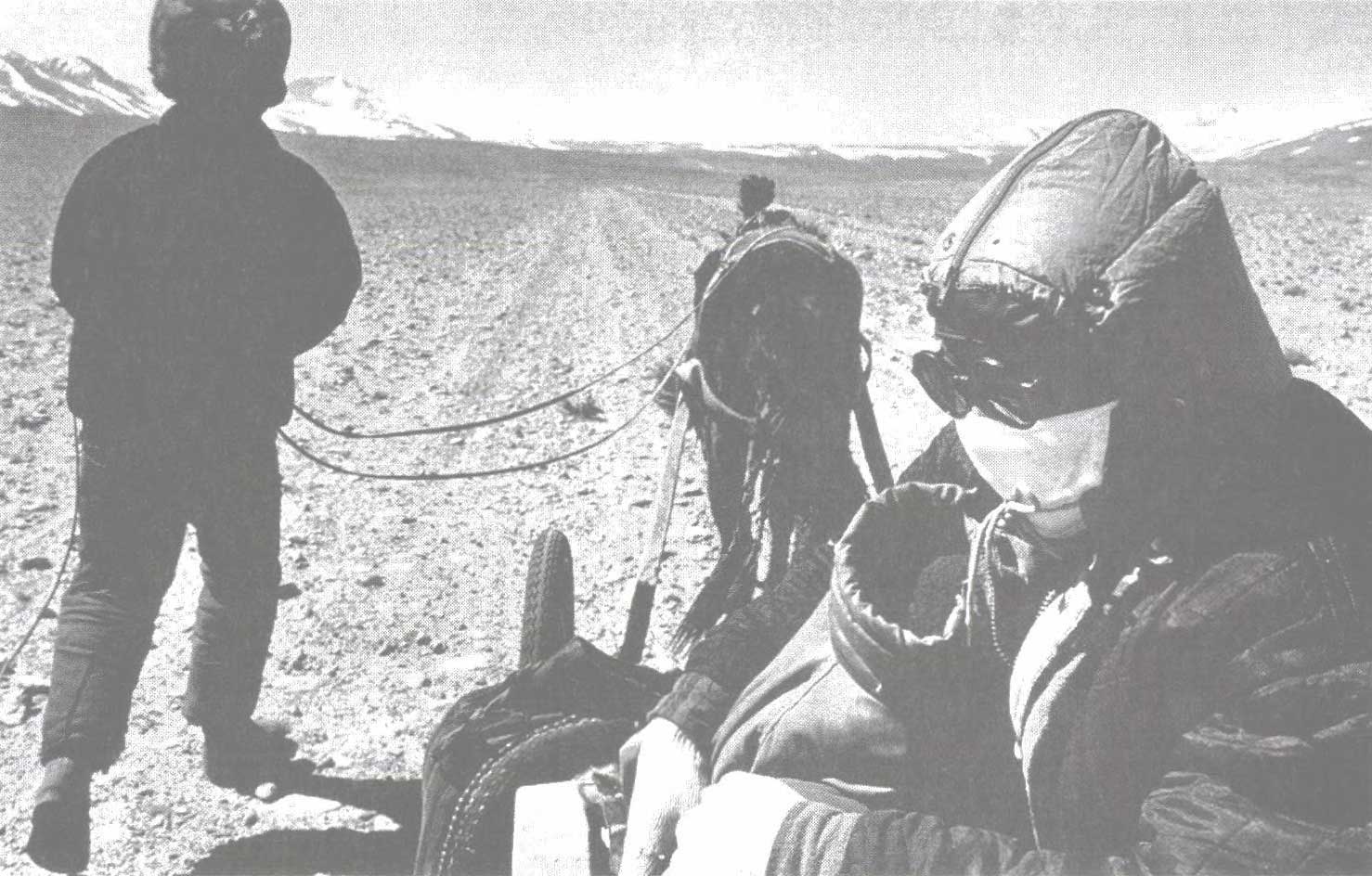

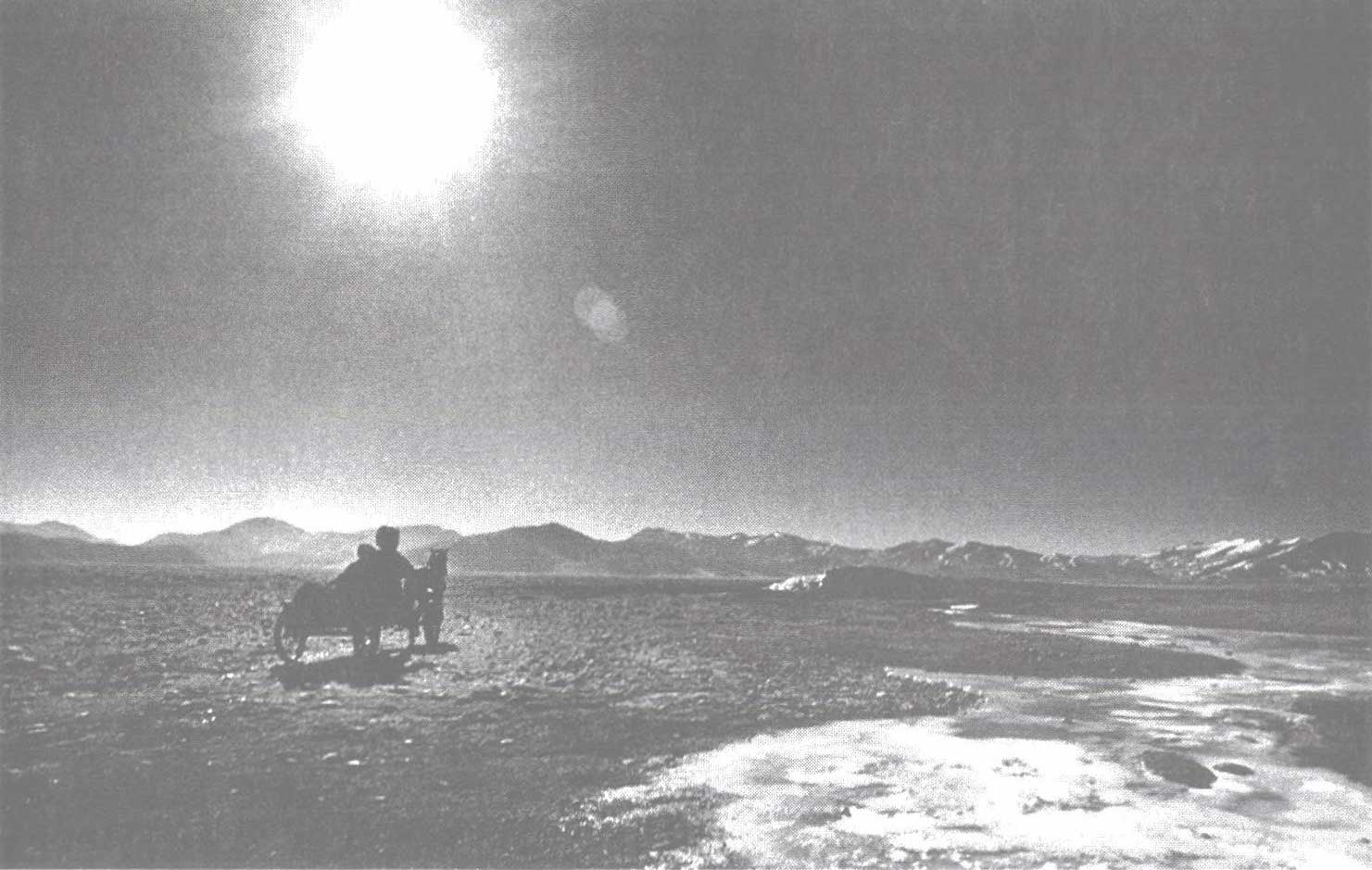

Day eighteen: This morning we hitched a ride which took us into the vast plateau. We passed a military camp on the outskirts of a small town and decided to continue on foot. We were very conspicuous; a military jeep could have picked us up at any time. At the sight of any moving object we threw ourselves into one of the small dips in the ground. Luckily, the objects turned out to be yaks or shepherds. We crossed frozen rivers, the ice cracking beneath our feet. In the evening we stopped at a small village. The village head was disturbed by my presence and took our permits to be checked overnight. We lodged with a local family. Yangdol made friends with the cat.

Sign in to Granta.com.