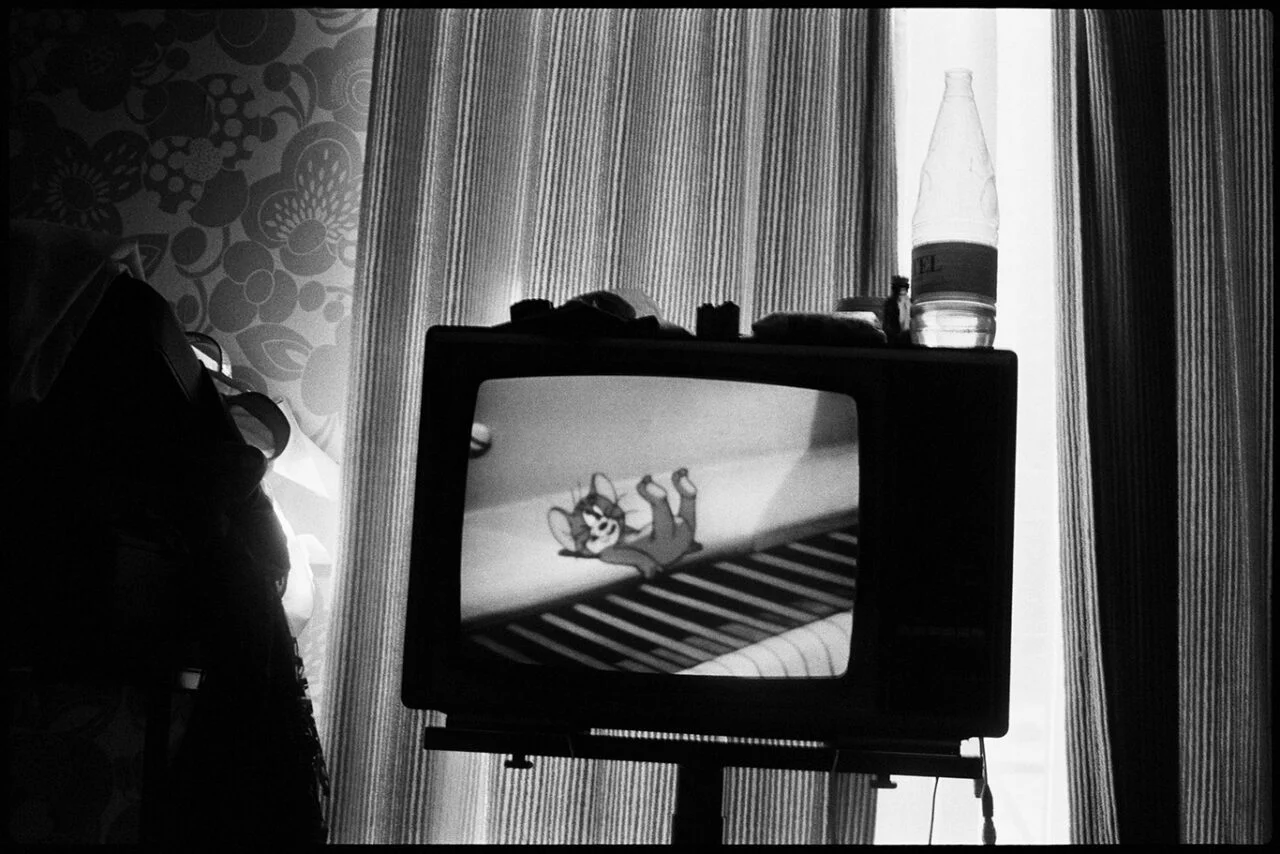

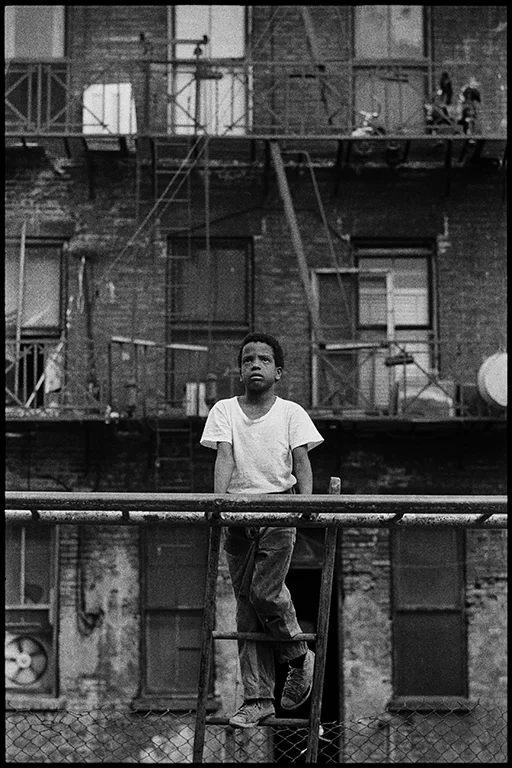

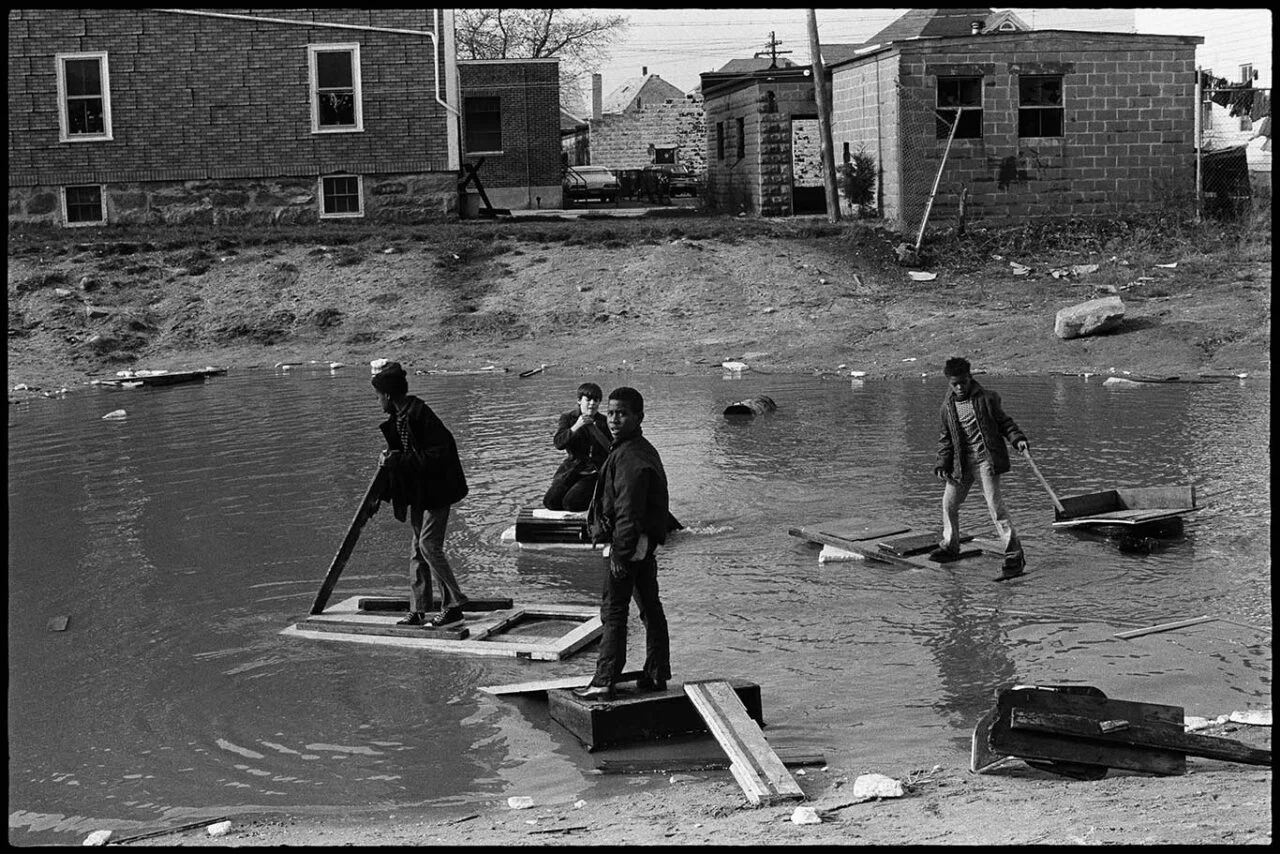

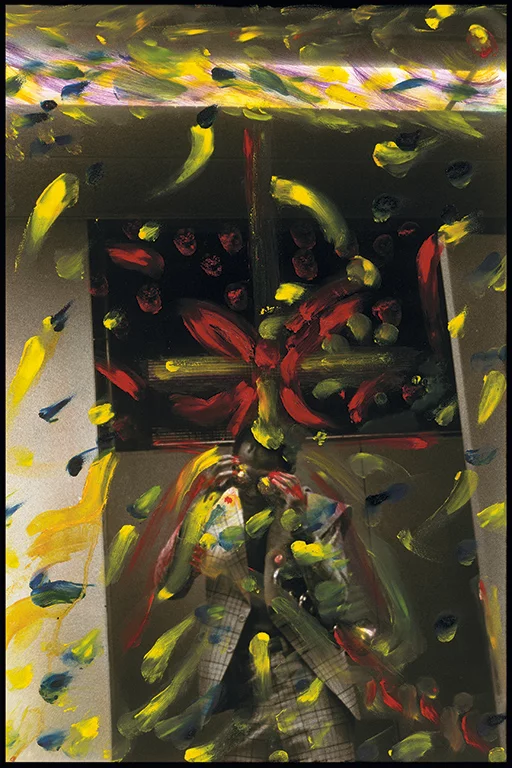

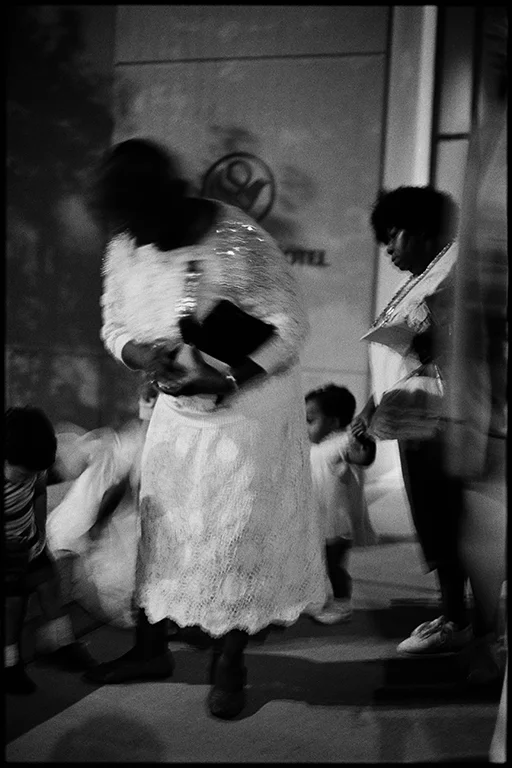

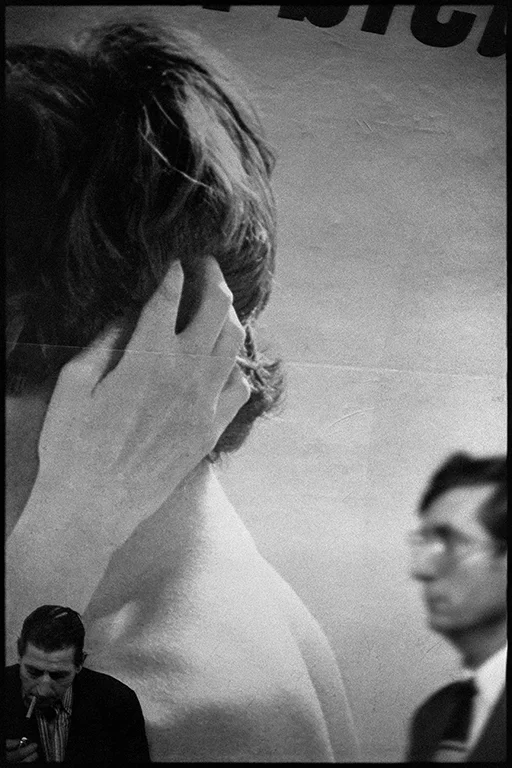

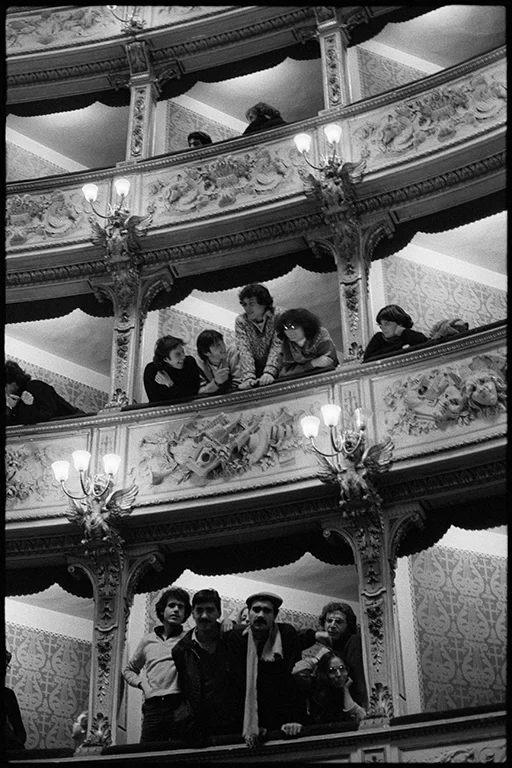

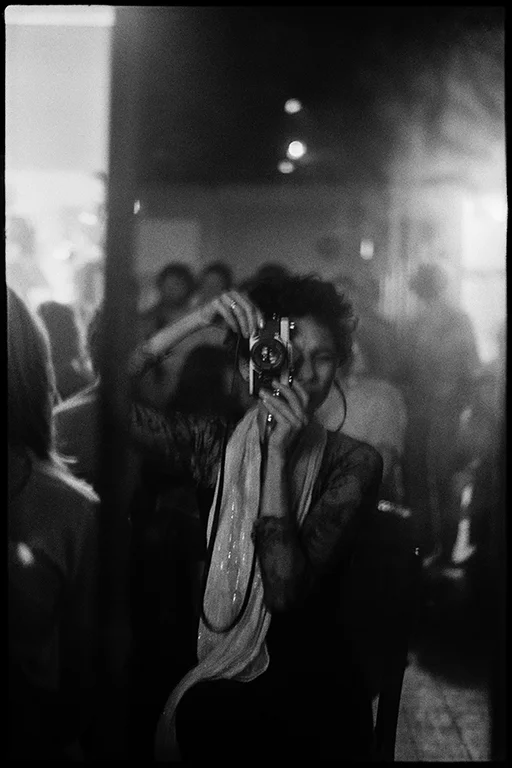

What unifies Ming Smith’s images? What draws five decades of mostly black-and-white photographs into a single affecting ensemble, transcending surface differences in subject and composition? The answer is not quite style; it’s closer, I think, to tone. Each picture seems to express a sensuous riddle and arrives at a tonal mixture of darkness-distance-warmth. These are images of strangers or celebrated performers, of children, cities, rooms, or skies. But that of-ness can feel secondary, at times even incidental. The fierce burst of articulate detail in one photograph and the smeared silhouette in another are linked by a mystic deference to the stirring fact of the phenomena. Documentation is not the point here. Some restless, formless element thrums deep within the portraits and stalks through every streetscape, trailing and sometimes meddling with the transmission of the message.

‘I do a lot of night shooting,’ Smith once told an interviewer, ‘and even in the dark, I look for the light – the way light comes in.’ This explains the streaks, beams, hazes, glows and abstracted reflective flashes that claw through the black space in her pictures, serving both as pictorial syntax and ingenious personal signature. Look at any photograph from her Jazz Series and you see in an instant: this was taken by Ming Smith.

But it’s possible to place Smith’s idiosyncrasy within a larger history – including that of jazz itself. Among her best-known work are a series of pictures she took in 1978 of Afrofuturist musician Sun Ra. She would later snap some of her most compelling photographs in her early thirties while touring with her husband, the musician David Murray, and his band, the World Saxophone Quartet. One of those images appears on the cover of their 1980 record W. S. Q.: the men of the quartet reduced to subtle blots of grey and black, the glare of their respective saxophones slashing the picture in a visual screech.

By that time, Smith had passed through her own powerful group experience. In 1972 she had become a member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of black photographers established nearly a decade earlier in Harlem. The name had been taken from the glossary at the back of Facing Mount Kenya (1938) by Jomo Kenyatta, the anti-colonial leader who later became Kenya’s first prime minister; in Kikuyu, kamoinge means ‘a group of people acting together’. The moniker broadcast not only the ‘African consciousness exploding within us’ (to quote co-founder Louis Draper), but also the wish for a robust, if intimate, forum, an institution that could cultivate individual talents while also confronting a shared predicament.

What could black photography be? Which forces was it struggling against, and what objective could it coherently strive for? These were old questions, debated grandly in the salons of the Harlem Renaissance and now refreshed with frank vitality in the era of civil rights. Kamoinge would go on to arrange group publications and exhibitions, even securing a makeshift gallery space. Visitors included Henri Cartier-Bresson and Langston Hughes, by then a kind of elder statesman.

The task was to practice fidelity to their people – to hold fast to social truth without lapsing into romance or the bleakness of cliché. Hence the disciplined reflexivity among the participants in the workshop. Critique sessions grew notorious for their bluntness, even brutality. The intensity of the meetings followed from photography’s historical link to documentary realism, which for black artists involved the bitter, ambivalent pressures of speaking for a group. Kamoinge sought new ways to capture black existence while asserting its variety and complicated dynamism. By 1972, Draper could write that ‘we could no longer stomach the steady diet of run-down tenements and sad-eyed tots’ because such shots so often became ‘an imposition rather than a commitment’.

It was around this time that Smith, fresh out of Howard University and making ends meet as a model in New York, found herself at the studio of workshop member Anthony Barboza. After overhearing him take part in a spirited debate about the purpose of photography – was it an art form or was it just nostalgia? – she struck up a friendship. She shared some of her work and was soon invited to join the collective: Kamoinge’s very first woman.

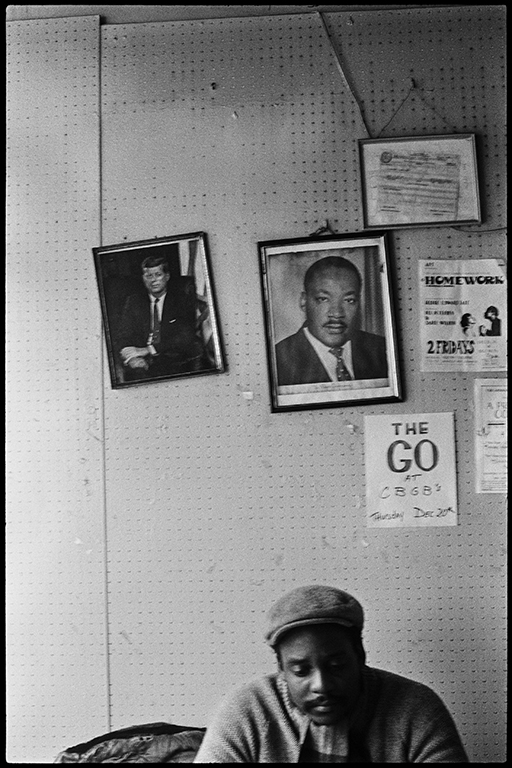

An emblematic episode, and not just for its lamination of Smith’s glamorous personal myth. Look at her pictures and it feels fitting that she crossed paths with Kamoinge just after the 1960s – overhearing a couple of men while waiting to be photographed herself. In one photograph included here, the portraits of John F. Kennedy and Dr Martin Luther King Jr hang at sloppy angles behind Smith’s guileless husband, appearing both heroized and marginalized, displaced by the motion of history, folded into the fabric of time. It is a photograph of photographs. It’s also gently ludic, as if to suggest that the booming questions of blackness and representation might now benefit from a more angular approach.

‘It was a community,’ Smith recalls of Kamoinge, ‘but eventually I didn’t really hang out with them. I was too much of a loner.’ She was also a dancer – she’d trained with Katherine Dunham – and a working fashion model. That’s how she became friends with and even photographed Grace Jones, years before the latter got into music. But Smith had taken pictures since childhood in Ohio, thinking of her various other pursuits as secondary or side hustles. She’d joined Kamoinge to learn, and she did: about printing, about paper, about all the decisive technical details that before she had fumbled through alone in the only photography class at Howard (where she’d majored in microbiology). She learned too from Kamoinge’s many ‘cold-blooded’ critiques.

But her life was taking place elsewhere. It was shot through with fragments of a different Manhattan, one somewhat removed from the older, male participants’ complex of concerns. ‘I didn’t live in Harlem,’ she says, by way of explanation. ‘I lived in the West Village.’ The geographical contrast is a classic one – Amiri Baraka’s exodus from the Village to Harlem was an extravagant, allegorical episode in the history of black American art, marking his repudiation of downtown bohemia and his embrace of the Black Nation. So it’s interesting to imagine a twenty-something Smith, for whom that uptown train trip was no more than a commute. Her 1979 photograph of Baraka, not shown here, is admiring, semi-candid and delicately blurred.

The blur is now seen as Smith’s trademark. She achieves the effect by slowing the camera’s shutter speed and standing very, very still. This technique flattens tonal ranges, gently erasing the distinction between foreground and background, at once collapsing pictorial space and driving the image further away. There’s something glyph-like in the resultant streaks of unruly light. Like writing, these photographs are attempts at particularity and explicitness, that nevertheless swing out into the pure form of the mark. They measure the distance between the writer and the thing she wants to touch.