Today, one in seven people is a migrant. This year, crossings of the Mediterranean Sea have already exceeded 300,000, and at least 2,500 lives have been lost in the process. What does it mean to be a migrant – or a refugee – in our time? What human rights can we rely on? And what hope is there for those who have fled their homes? Granta asks its authors to share their reactions to this profound human crisis. What follows is a collection of statements, poems, images and personal reflections from across Europe and beyond.

‘Our Government can only talk in numbers, so too most of the media, including the BBC. Until yesterday, when Yvette Cooper finally acknowledged the Syrian refugee crisis, leading Labour figures were cowardly too, staying silent. Social psychopathy is the result. Thousands perish as they try to get into Europe; asylum-seeking women miscarry on the streets; children are starving and traumatised; young men look trapped and emasculated. Those who have decided not to care will not be moved. (Millions do care and do what little they can, but this is a humanitarian disaster which requires a pan-European response.)

Maybe this is the moment, the image which breaks through the emotional and political fortresses. Remember that little naked, burning girl in the Vietnam war running away from bomb attacks? That single picture turned American public opinion against that terrible war. Or the first photographs of young Malala Yousafzai after she was shot on a school bus? Until then most Pakistanis were in denial about the Taliban in their country. After the shooting they had nowhere to hide.’

Read Yasmin Alibhai-Brown’s full article in the Independent

My mother was born in America, which of course does not mean she was a Native American. Her mother’s parents were recent émigrés to the United States, the father of German stock, the mother from Ireland. I know their surnames but nothing else about them. I do not know if they were economic migrants or some other kind of migrant. I do not know if they left or fled.

My mother’s father could trace his family’s presence in America back to the Mayflower, the ship of ‘pilgrims’ or religious sectarians who left, or fled, Europe in 1620. In the eighteenth century, one of his ancestors married a woman of French extraction, perhaps a Huguenot who left, or fled, France, or else one of the earlier wave of French settlers who were repeatedly dispersed around the North American continent as the British broke up colonial New France.

I am no genealogist. But even with so little investigation of the matter, it is obvious that I have ancestors from several generations who have left, or fled, one country and settled in another. Some of these journeys may have been undertaken for reasons of ambition, but some were clearly forced. My ancestry may be a little more mongrel than some (it is certainly a lot less mongrel than many), but I do not imagine this makes me any kind of exception. We are all the sum of yesterday’s refugees.

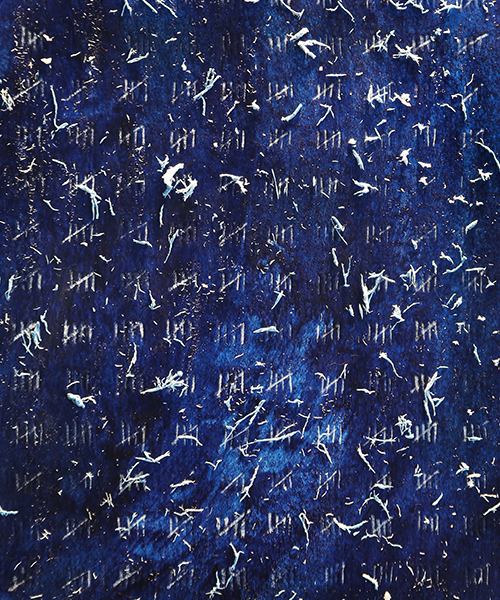

This is a detail from a drawing recording all 2,600 plus deaths in the Mediterranean this year. Each person is marked by a hash mark, a system of measurement where four lines with a cross through them signifies five units, usually used to tally ongoing events. This image represents a fraction of the full painting – the 2,600 lines have been drawn by hand and then rubbed out to signify each person’s passing, and the resulting erasure marks evoke the dangerous sea.

It is hard to read the character of the general public. At times it seems they are selfish xenophobes who don’t care about poor migrants and see them as little more than parasites. At others, it looks like they are easily moved by images of desperate people and are willing to share their country with them. Will the real ‘will of the people’ please stand up?

But of course, there is no such thing. Character in the individual is rarely consistent. People can be brave around snakes and cowardly around the rich and powerful; honest with colleagues, caddish with spouses. Any psychologist will tell you that how we behave is extremely situation dependent. More than that: how the situation is framed will alter how we react.

In dealing with this crisis too many politicians have been trying too hard to read the public mood when it is their job to help shape it. Talk about refugees, families in dire need, people fleeing persecution, a noble tradition of welcome and hospitality, the ability and willingness for each area in the country to take just a dozen or so people in – talk like this and people become willing to help. But it is also easy to see what happens when you talk instead about swarms of illegal migrants, public services straining to cope, borders and security being breached.

This is not about patronising the public, saying that they can be led anywhere if you use the right rhetoric. It is rather about respecting people’s ability to come to fair and humane conclusions when good arguments are presented in clear terms. The fate of many refugees might depend on more political leaders recognising this and acting accordingly.

Syria was my home.

I lived there in exile as a child. My parents called it ‘exile’ because we couldn’t be in our own country, Pakistan. Because Pakistan was too dangerous, too violent, because there was no justice there.

Syria gave us refuge. My father had come from Pakistan. My mother from Lebanon. And me, from somewhere in between.

Syria protected and welcomed us into their country.

I wonder why my parents never called us refugees?

A lorry arrived at the sawmill this morning, loaded with logs from Normandy: oaks, which you have to cut with caution since wartime shrapnel will sometimes break the blade of the bandsaw. The driver has a grab and unloads steadily, working his levers, speaking of queues and scenes on the ferry to anyone who happens to be passing. Halfway down he uncovers a scarf, in a space between trees weighing several tons. It is blue and yellow and embroidered in white with the word ‘Fenerbahçe’. One of the boys who is checking the timber has a look on his phone, and finds that this is a Turkish football club. The scarf was loose, not trapped, not attached to anyone, but still the driver has to stop for a roll-up. He is a nervous man who once burst into tears when he was talking about coming through Calais.

My passport is thick with the extra pages I added a few years ago, when I ran out of room for the stamps I was accruing. An American living in France, with a partner from the UK, I frequently cross over the invisible borders between those countries that are inscribed, respectively, in the Eurostar terminals at the Gare du Nord and St Pancras. Every crossing has to be marked. I gain entrance to Britain with some difficulty, which is usually resolved upon the basis of my answers to questions like: what are you doing in our country? where do you live? where do you work? I envy my husband his sober maroon passport, which slides him across the border from one EU country to another.

On recent trips to London I’ve encountered another kind of resistance. As we hurtle unimpeded through the Pas-de-Calais region en route to London, something’s creating drag on the tracks. It’s the knowledge that somewhere out there, just to our left, or just to our right, there are three thousand people in a camp with thirty toilets, caught in administrative limbo, desperate to get to Britain. At night they try to jump onto the tops of trucks, or slip into the tunnel and try to run across, only to be caught at the British border and sent back. All of us on the train, we who have one way or another passed the test at the checkpoint in Gare du Nord, with our various passports, we speed through this place where so many others have stopped, caught.

Passports were invented at the onset of the First World War to keep track of people, slow down their movement. Sure there were safe conduct papers before that, issued by the king, or whoever, but passports as we know them came about as a result of the British Nationality and Status Aliens Act 1914, which redefined who could be considered a British subject. It took effect on 1 January 1915, and stated:

(1) The following persons shall be deemed to be natural-born British subjects, namely:

(a) Any person born within His Majesty’s dominions and allegiance; and

(b) Any person born out of His Majesty’s dominions whose father was, at the time of that person’s birth, a British subject, and who fulfils any of the following conditions, that is to say, if either—

Et cetera. My husband goes back and forth, a subject of the kingdom. I occasionally drop in, natural and adopted child of revolution, a citizen of the republic. I treasure my ability to cross. I grow angry when it’s under threat. The European Union was created to override passports, to facilitate the free circulation of people and goods between countries that decades before were eviscerating each other on the battlefield, and in the cities. In a zone without passports, it seems craven to distinguish between those who have a right to circulate freely (citizens, subjects) and those whose passports are the wrong color, or who have no papers at all. But Britain holds itself at a distance from this passport-free zone, and cracks open its doorway only to those who know the password.

On the train, seated comfortably in my second-class seat, I look out at the world streaming by, long grass, cement buildings, chain link fences, and think of the sign on the back façade of a church in Queens that I see when I’m at home, riding the Long Island Rail Road to the city: ‘Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by?’ (Lamentations 1:12).

It is not nothing to those of us who pass by, our passports growing heavy with administrative ink and paper. It is not nothing to those of us who travel with lighter passports, as I will soon, now that my French citizenship has been approved and I will be issued my own slim maroon passport, the kind the customs agents look at and slide back to you, without the official pounding of the stamp.

It is not nothing to those of us moving quickly through the French countryside that there are so many waiting out there, whose daily lives, we hope, will be improved thanks to the fundraising campaigns we’re giving to, and the petitions we’re signing, and the generosity of the people who pack up their trucks full of supplies and drive to the camps, instead of past them. We would like to help any way we can, but the ultimate decisions about who goes where don’t lie with us. The people in the camps (I imagine, I read interviews, I try to understand) are waiting for more than a better quality of life in limbo. They’re waiting to be let out, to move on, and then to put their bags down somewhere, for their answers to the border questions – what are you doing in our country? where do you live? where do you work? – to be no different from those of the passengers speeding by on the endless, endless Eurostars.

The health of a society can be judged by how well it cares for its most vulnerable citizens. The current refugees are children, women and men who desperately need the rest of the world to understand that this can happen to anyone – and it won’t go away.

The refugee and migrant crisis in Europe is an opportunity to reach out, engage politically, act humanely and do the only decent thing anyone can do – imagine how it would feel if you were unsafe and your children’s lives and family’s future depended upon the understanding of strangers?

All populations are historically transient. Humans are a migrant race full stop. These people could easily be us, it’s time to get our priorities straight and offer our collective resolve to continue to challenge brutality and its effects on ordinary citizens in countries all across the world.

They gave themselves away with the words on their T-shirts.

Invaders. Mystery space riders.

Army life. XVI Soldier 4. Spec. Mil.

Yes, they were an army of invading aliens

So we built a fortress to repel them.

This is a defining moment where we must decide what kind of country we want to become. Do we allow ourselves to contract, ruled by fear and old habits of thought that insist: ‘there’s not enough to go round?’ Or do we show the world – and ourselves – that we stand for compassion, courage and generosity of spirit? There may be newspapers and politicians who delight in feeding the delusion that our islands can somehow be miraculously insulated from global problems, that the cataclysms engulfing other countries are somehow not our concern, and that responsibility for helping those affected lies elsewhere. The reality is that we could easily match other EU countries in admitting tens of thousands more asylum seekers. Not to do so would be to betray not only those in need of help, but ourselves. The latest arrivals in Europe are not the other. They are us.

My grandfather, an anti-fascist, fled Mussolini’s Italy and was welcomed to America. So as a first-generation American who returned to live in Europe, I am horrified and embarrassed to be on the reverse side – part of a continent which is offering no humanity, no empathy for the refugees (I don’t like the term migrants) who are fleeing either economic devastation or horrific war. How can we be so short-sighted? How can we forget the war that devastated Europe seventy years ago? How can a leader like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán have so little compassion, empathy, humanity for his fellow human beings?

Over the twenty years I have worked in war zones and lived and talked and cried with refugees, I know one thing: you lose your status, your dignity, your identity. You don’t want to be in someone else’s country, but you have no choice if you want to stay alive. All you want to do is go home.

The least we can do for these people now is offer them some dignity – shelter, schools for their children, even a meal. I urge every single person who lives in a European country to just think small – prepare emergency kits for those people arriving – with little things that will make them feel more like a human being: a clean towel for instance. Metro tickets. A blanket.

And pressure your governments to take more refugees from Syria, Iraq, Africa, and places where they must flee in order to survive. If we lose our sense of humanity in these desperate times, then we have lost everything.

Why do we believe that some people have the right to forbid others from moving from one country to another? ‘Asylum seekers’ is perhaps the wrong term. ‘Staying alive’ seekers might be better. One day the human beings of planet Earth will look back at our era and think of us, those who claim to love freedom but who live in societies that legalize migrant detention and deportation, with the same puzzlement that we think of those who lived in societies that legalized slavery.

The little girl was looking out of the train window. Her family were slumped across the seats in the carriage, exhausted after the arduous journey through Turkey and Greece. Hundreds of refugees and migrants had boarded a train in Gevgelija in southern Macedonia, heading for Serbia and beyond. I was travelling with them.

What was she thinking about? The life she had left behind or the one ahead? She would have been eight years old, maybe, kneeling on the table jutting from the side of the train, watching the red roofs and green fields of the Balkans flash by. I thought: she will always remember this journey.

On the border between Hungary and Austria, 1000 kilometres nearer their longed-for destination of Germany, families scrambled to get on buses. Most were Syrians, but there were also Afghans, Bangladeshis, Iraqis, Pakistanis and others. I met two young men from Senegal who spoke in broken French – their sole language was Wolof. How had they made it this far? A small Syrian boy smiled as he brandished a plastic brontosaurus. Any fear or exhaustion he might have felt had been extinguished by this wondrous new possession, the gift of an Austrian volunteer.

What is it about the children I’ve seen as I report on the refugees and migrants taking perilous journeys through the Balkans to northern Europe? I’m not normally sentimental, but I have found myself in tears several times in the last few weeks.

I think it must be an instinctive response because in children we see humankind’s determination to survive against any odds. If we didn’t have empathy the human race would have died out long ago. The story of humanity from its origins is one of migration, birth and adaptation. This summer of mass movement is just a tiny chapter.

A Short European Memory

When I arrived at the harbour, I saw barbed wire and police all around. The faces of the policemen seemed frozen to me, without expression. The faces of those desperate refugees, around the harbour or in their dirty tents, radiated something like the hope in a better tomorrow.

Going back to my hotel, I thought that not very far away from here, some seventy years ago, there were also refugee camps of Displaced Persons, ‘crammed’ with desperate lives: native Europeans who were coming out from the cruelty of WWII. Back then Europe was not simply on the edge of the moral and existential abyss but rolling into it in a free fall. As refugees usually do, they were looking for some safer place to go, like the USA, Canada, Australia, or Latin America or Palestine.

Now, most Europeans have mostly forgotten about all of this. (Europe is the continent where Museums of Immigration constitute an exception – even though the idea of the Museum came from Europe.) Now, European governments are afraid of being simply human toward such human desperation reaching the European soil.

Europe, my love. You have such a long history; and oftentimes such a short memory. That’s where your troubles come from, I guess . . .

A few months ago, Cameron referred to the humans at Calais as a ‘swarm.’ This epithet was rightly condemned; Cameron subsequently denied that it ‘dehumanised’ anyone. Though this story has receded, it is important to mention it again, and again, because consciousness and language are intertwined. Words can enshrine obsolete ideologies, preserve ossified metaphors, or can be deliberately manipulated, for the purposes of propaganda. We experience such semantic occlusions every day, even in societies that purport to be ‘free’: ‘extreme rendition’, the ‘War on Terror’, ‘The patriot Act’ and so on.

Cameron knows, of course, that people do not swarm, but insects do – ants, spiders, locusts. The idea, presumably, is to insinuate, to create an atmosphere in language. Equally, Cameron’s government has advanced the calculated euphemism ‘austerity’ and defined the newly-elected leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, as ‘a threat to security’ – while nominating itself as the party of ‘stability.’ Such terms enforce a carefully distorted version of reality. More recently, Theresa May has argued that those who have balked at her creepy surveillance protocols are ‘putting politics before people’s lives.’ This seeks to merge and condemn the myriad opponents of her insidious definition of ‘security’. Meanwhile, the greatest distortion of all is the way in which governments blame the victims of global conflicts and economic crises for the asperities they endure. Cameron’s metaphorical language implies that the people at Calais are not, conceivably, in any way, victims, but insects. It sounds like dystopian sci-fi; but, alas, it is real life.

As writers, and readers, we are powerless to avert bloody conflagrations or global socio-economic iniquities – even as we protest (in ‘swarms’) against them. But we can, at least, decry these calculated manipulations of language. How many further such distortions must be exposed, before our governments tell the truth?

On just the other side of the Channel people live in destitution, scraping together an existence as they wait and hope to come to Britain. In the Czech Republic people have been rounded up on trains, their arms branded with marker pens before they are held in detention. In Hungary the police have stopped people with tickets from boarding trains to Germany. In the Mediterranean people are floating through night and day on vessels that are barely seaworthy. Many of those vessels sink, and the people on them, like Aylan Kurdi, never make it to the other side alive.

These are people – treated differently from me only because of the country in which they were born. I have just one simple demand to the Government: treat these refugees as human beings, not statistics. The nation has woken up to the humaniatarian crisis occurring on our continent – it’s time that ministers also open their eyes.

Heinrich Böll called the twenty-first century ‘the century of prisoners and refugees’. Being a refugee has in many ways defined the European experience and what it means to be a European. Today Europe is facing a refugee crisis from the outside, how we handle it will define the European project for many years to come.

And yes, Europe means Britain as well.

Faced with an increasing stream of refugees from Austria in 1938, the British government set new restrictions on entry. The move, however, drew extensive criticism from the public. The government had to grudgingly respond. In 1939, as other countries imposed ever tighter immigration restrictions, the British sent four million pounds to Prague to assist refugees, admitted Social Democrats from the Sudetenland en bloc and welcomed ten thousand mostly Jewish children from Greater Germany.

Let’s hope the British public can achieve a similar policy change today.

courage |ˈkʌrɪdʒ| noun [ mass noun ]: the ability to do something that frightens one; bravery; strength in the face of pain or grief.

It takes courage to leave your life behind and seek shelter elsewhere, not knowing what you may find ahead. It takes courage to take your small children and sleep with them in the street, hoping that help is coming. It takes courage to go out and help, to put yourself in another’s shoes, to share your resources. We, in Europe, need to find the courage to do what it takes to help Syrian refugees. For we never know when we will need another’s courage to help us.

If you look deep enough, we’re all immigrants, sometimes by choice but often not. I’m an immigrant on all sides. My grandmother caught the last train out of Gotenhafen (now Gdynia) before the Russians came in 1945. Her daughter, my mother, has ended up living in Texas, which was partly settled a hundred and fifty years earlier by Germans escaping unrest in Europe. My father’s family were Hungarian Jews until they arrived in New York; they’re Americans now. Eight years ago I became a British citizen.

There may be complicated questions about nations and borders to be asked, but they will never be permanently resolved, and in the mean time there are much simpler questions, about our duty to people who need our help, now, which should be simpler to answer. In the long run history is kind to the countries that are kind to immigrants.

Empathy and the Refugee Crisis

In the weeks after Nathaniel’s birth, there was one image I could not shake from my mind. It was of the mothers who gave birth in the sinking smuggling boats, their stories told by survivors who had witnessed the deliveries and by rescue divers who found the bodies of babies still attached to their mothers by their umbilical cord. I had just experienced a pregnancy and birth, that blooming of hope, the excitement at the onset of labour, the hours of terrible pain then the euphoria of the delivery and wriggling new life in front of you.

Imagine doing all that, but in the darkness of the rotting hull of a fishing vessel, surrounded by so many bodies in the grip of fear and panic, inhaling hot air saturated with the smell of human waste and diesel fumes, lost in the middle of the sea and knowing that you were drowning.

Would that rush of pure, indescribable joy when your baby finally leaves your body still be there, even if you knew you and the child you brought into the world were about to die? Did they have a chance to hold their babies, to try and comfort them? Did anyone help comfort them at that moment when they were delivering that doomed life, or was the panic so complete that they were alone?

Pinter for Dogs

‘I don’t see why he bothers you so much.’

‘He stinks. He chews everything. He costs a fortune to feed and another fortune in damages. He’s probably riddled with disease. And this is MY PLACE!’

‘I can’t just put him out. He won’t survive. ‘

‘Of course he will. The streets are full of them – lurking round shop doorways – begging –’

‘And we could give one of them a home.’

‘Why just one? Why not all of them? Just leave the door open – let them all in!’

‘If everyone let someone in there wouldn’t be a problem.’

‘Course there’d be a problem. Country’s overrun, because everyone knows we’re a soft touch.’

‘It won’t hurt to let one of them stay.’

‘You’ll be offering to marry him next. I, Aston, take thee, Davies, as my lawful wedded dog.’

‘All right, Mick.’

I think that Britain, with its colonial past and long tradition of sea-going, is shaped by migrations and migrants of every kind. I imagine that each of my migrant forebears needed a bit of help on each arrival, a bit of human decency from people who could imagine what it might be like to start your life over again in a new place, but once settled I don’t think you could say we’d been a burden to any of the countries where we’ve lived. Some of us are academics but there are also tradespeople running businesses, doctors, teachers and accountants. We’re British (or American or Australian). We pay our taxes. We give to charities. We are, in fact, not really exotic at all.

On Leadership

The cleanest election I ever witnessed was the election for the leadership of the youth umbrella of Hagadera Refugee Camp, one of the five that make up the world’s largest refugee complex: Dadaab. Dadaab is located in northern Kenya, in a red desert that blends seamlessly into Somalia across a border that was drawn by white people somewhere far away and long ago. The nonsense of the word ‘refugee’ rather than ‘nomad’ or ‘indigene’ is nowhere more starkly obvious: this land is their land yet they are confined to a camp, unable to leave or to work. Indeed, they have lived like this for twenty-five years. The youth contending for office have known no other horizon.

Each candidate is given the same amount of time to make their pitch. There is a female and a male chairperson of the umbrella that collectively represents all the young people in the camp, and they are the majority. The refugees take their elections seriously. They are frighteningly aware that their people in war-torn Somalia do not have the luxury of democracy. They also know the value of leadership. They blame the war on bad leadership and they blame its endurance on the lack of it, as well as on the cynicism of Western leaders. They see that the only difference between the stance of Germany and Britain in accepting refugees – both countries struggling with right-wing xenophobia – is strong leadership. They are, largely, right.

In a close-knit refugee camp, abuse of office is a hard crime to commit: people hold you accountable. If you do not represent the will of the people, you could be dragged through the streets. And the will of the people is hotly, fiercely, daily, expressed. It is unmediated by a gutter press. It is buttressed by the moral leadership of elders and imams. In a place where newly displaced vulnerable people arrive in waves whenever fighting erupts over the border, helping the newcomers is a simple duty, it is daily life. When someone needs food more than you do, you go hungry. Morality is not a discussion, it is a habit born of culture. And the young people know that a leader who goes against the culture is not worthy.

The votes are cast, the ballots counted, witnessed by an independent commission, verified and announced. The concession speeches and the victory ones all sound the same: they are about unity, tolerance, compassion and duty. There is much reference to Barack Obama. They know that their country, and the world, needs better leaders, and they are determined to be the change.

People Run

People run away from war:

my father’s uncle and his wife

ran away from war.

They ran from one side of France to another.

But the authorities divided people up:

some who ran away were good;

some, like my father’s uncle and his wife,

were not so good:

they were not born in France.

So they were put on a list

and had everything taken away from them.

They heard that people like them were

being put on trains and sent away to the east.

So they escaped and ran across France

again.

This was a good move,

they were safe now,

all they had to do was wait.

While they were waiting

the authorities in this place got defeated,

they were seized, put on a train

put in a transit camp, then on another train

to another camp,

where they were killed.

People run away from war.

Sometimes we get away.

Sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we’re helped.

Sometimes we aren’t.

Refugees and Europe: The Swedish Exception

No other nation in Europe comes even close to Sweden in refugees per capita; more than twice as many as number two, Switzerland, four times more than Denmark and Germany, five times more than France, twenty-five (!) times more than the United States. If the EU as a whole, with a population fifty times that of Sweden, had received refugees in Swedish proportions it would certainly have made a difference.

This is not to say that a ‘Swedish’ proportion of refugees is possible or even desirable on an EU scale, only to say that in a situation when Europe is facing its worst refugee crisis ‘in our era’ (Amnesty), with millions of people fleeing war and persecution in the Middle East and Africa, it might be worth contemplating what has so far made the difference between, let’s say, Sweden and Denmark.

Let me suggest that it might have something to do with how nations view themselves and what they take pride in being seen as. I will not venture into the national psyche of Denmark but I would argue that post-war Sweden during forty-four years of uninterrupted Social Democratic dominance, not having been at war since 1814, had come to pride itself of being a model society based on universal tenets of social justice and human rationality. A national narrative based on memories of a distant past was effectively replaced by a narrative based on memories of an ongoing success story. Similarly, the moral ambiguities of Sweden’s neutral position during the war were happily subdued by a sense of moral clarity in neutral Sweden’s positions after the war, offering a ‘third way’ between Soviet Communism and US Capitalism, supporting anti-colonial movements in the ‘third world’, happily touting the universal applicability of the Swedish model, generously opening its doors to the persecuted and oppressed.

Since then, the world has changed and with it the political and economic preconditions for Sweden’s exceptionalism. Instead of the world becoming more Swedish, Sweden is rapidly becoming more like the world.

With one conspicuous exception, the refugees.

There is little reason to believe that this exception will last. Not when anti-refugee parties are having their day all over Europe. Not when such a party has become the third largest in Sweden. Not when even a modest redistribution of some 40,000 refugees among EU member-states cannot be agreed upon.

What would it take to turn the downward spiral of anti-refugee policies around?

Or more precisely, what would it take to make the Swedish exception a source of inspiration rather than a source of resentment and mockery?

Sea of Refuge

I might have been that Syrian refugee, her children swallowed by the ocean. Her shrieks, her pointless pleas had found no foothold in the rocky walls of thieving militias or the shrunken hearts of murderous Isis.

Alone beneath a darkening sky, lashed to a feeble ladder clutching her babies: ‘We can survive, I will be Sinbad the Sailor’ – desperate to believe that benevolent winds will overcome a churning sea. ‘We will not starve, be raped or murdered for a wrong answer. Better to drown in the purity of water than endure the savagery of my country now ravaged by cruel men.’

Forty years ago I had despaired. Beriut could not protect me from its snipers, bombs, explosions and militiamen at checkpoints hunting for men of other faiths. My apartment no longer the peaceful oasis, walls shaking, windows opening to the whistle of random bullets. An explosion killed my neighbour in a bread queue, another died from a stray bullet while attaching pegs to her laundry – blood spraying out across her limped sheets.

Leaving home is never easy. My mind froze – the reassuring familiarity of the wall’s cracked paint, the Chinese plate that had never left our kitchen counter, even the squeaking wardrobe comforted me. Telephone calls from anxious friends, the flutter of palm doves perching on our balcony imploring me to stay.

But we had to leave and I fled with my babies to the safety of London. Even today I vividly recall my father’s parting hugs, kisses and final words: ‘Poor daughter, fleeing to seek safety in an alien land, and what of my poor grandchildren?’

To the mother of those small children and the thousands who in their desperation continue to die at sea: ‘Many continue to betray your destiny through distorted notions of faith and tribe.’

Refugees from Europe begot me: four Irish Catholic maternal great-grandparents fleeing the brutalities of British colonialism and discrimination, two Eastern European Jewish paternal grandparents fleeing pogroms and other forms of anti-Semitism; it equips me with a skeptical view of Europe as a place of tolerance, though there are moments and countries that have done well and even occasionally gloriously. Right now the Europeans welcoming immigrants – a Scottish minister, a crowd demonstrating in Paris, people reaching out in Hungary and Austria – are making the news, though these kind gestures are not overwhelming official policy. The USA took in millions of refugees like my progenitors, and still does take about a million legal immigrants a year; many millions more come in quietly through the back doors. My country also does a remarkable job of creating other refugees – from the North American Free Trade Agreement that broke the back of Mexican farmers to the drug wars my compatriots’ endless appetite for numbness and unregulated guns feeds to the people whose places have been destroyed by war in Iraq and elsewhere – and those who have no refuge: the homeless.

Here in San Francisco I move daily among undocumented immigrants from Latin America, many of them indigenous people whose roots on this continent reach all the way to the bottom and the beginning of time, and the homeless who are often also mentally ill, whether ill because homeless or homeless because ill is impossible to determine. There are now more Latino than white people in my home state, California, which seems like a good thing to me, a break-up of the old hegemony. Hearing Europeans insist that theirs is a Christian country or continent makes me wince as if they were endorsing genocide again, and perhaps they are, though it’s not worse than the people who insist that the USA is or should be or ever was a white country.

There were always many peoples here, I try to keep saying, as I live in a Latino neighborhood on Ohlone land, just across the Golden Gate from the Coast Miwok land I grew up on, in a part of the world that Spain claimed and then the US stole from Mexico. So far from Syria and Europe, I think also about the fact that the Arab Spring’s uprisings and the Syrian civil war have as one major cause climate change, the climate change that made crops fail and bread prohibitively expensive in Egypt in 2011, that ravaged Syria with several years of scorching drought and destroyed the livelihoods of so many farmers and is doing much the same in other parts of the world now. Climate change is going to create refugee crises on a far larger scale than this one, and working to address climate change is one of the important things we should all be doing. And that I try to do. That and to not believe very hard in national borders, especially when human rights and survival come up against them.

Earlier this year, my translation of By Night The Mountain Burns by Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. I first met Ávila Laurel in Barcelona, where he was living in exile. Yes, he said, Barcelona was a lovely city and he was grateful to be there, but he didn’t want to be there, he wanted to be in Equatorial Guinea, where he’s from. Equatorial Guinea is ruled by a murderous dictatorship and Ávila Laurel had become persona non grata for having spoken out against it.

I have also lived in Barcelona, though I did so out of free choice. I have lived in London too, as an economic migrant. People in Sheffield, where I’m from, didn’t envy London, but they did Barcelona: Ooh, thy lucky beggar, I wish I lived out there, they’d say. But I don’t think they really meant it: their lives were in Sheffield, for better and for worse. They certainly didn’t mean they wished for Threads-style apocalyptic destruction to force them to be uprooted to Catalonia. Alas, we live in a world where empathy seems to be in increasingly short supply.

The machinations of political leaders are a mystery to most of us. Why do things truly happen as they do? Most of us are only cogs in the system; bewildered and trying our best. As people whose places we could be in but for a fortunate accident of birth and circumstance swarm thickly into Europe, the immediate response should be to grasp the hands of those who reach for them. You are me and I am you.

I am writing this on the day that the media has been overrun by the images of two small boys, the children of Syrian refugees, whose bodies washed up on a Turkish beach. They are so small that, cradled in the arms of the soldiers who scooped them off the sand, they look like a pair of broken dolls. Their tiny feet clad in matching miniature trainers are almost too poignant to look at. Did we really have to wait for this tragic picture to engage our empathy and sympathy? Did we really need to stare into the faces of dead children to understand that refugees are not an abstraction but people: people with families and fears, dreams and hopes? How did we allow our empathy to be stolen from us by self-interested politicians and cynical polemicists who label refugees as ‘cockroaches’ and use ‘the migrant issue’ to distracted us from the real problems that undermine our quality of life? How did we forget that famine and slavery are tortures that all of us would seek to escape? How did we not know what extraordinary courage it takes to leave behind everything that you have ever known to take a punt on something better? It is time to step up. After all, somewhere in all of our family stories is a migrant, a brave soul who struggled to surmount history’s terrible backhanders in order to forge a better life.

The migrants are really refugees; their homes have become intolerable. They have lost hope in revolution and risk everything. The people storming Europe’s gates are a testament to the failure of an international system – foreign aid, the United Nations – that advances the interests of great powers and has undermined accountable governments across the world.

Budapest 2015

We leaned against the border posts. They were standing a metre away – in Serbia. Twenty men appeared, some carrying children, among them a doctor, an engineer, and a mathematician. A month on the road, they said, or two. Apart from the war, their grimmest memories were of the boat, the longest three hours of their lives, but that was in the past. Now, their wives were waiting in the nearby bushes for the signal to continue the journey, but first the smugglers had to find them here – there’s hope in the people-smugglers, not the Hungarian authorities. They would not go a step further without the smugglers, because on the Hungarian side there’s compulsory registration, there wasn’t any in Greece or Serbia. Anyone who gives their fingerprints in Hungary, said the itinerants with certainty, even if he gets to Germany, will have to go back to Hungary, and it’s a poor country, the people here don’t like refugees who come from a war zone. The whole time others kept passing us, more and more of them, about fifty in the course of an hour, whole families on the railway tracks, the registration evidently didn’t scare them, and the policemen weren’t detaining anyone. At the road, only a kilometre further on, the new arrivals were told to wait. Some portable toilets had been set up there, and tents, where the mothers were changing their babies and a pregnant woman was resting. The authorities knew where these worn-out people would enter the country, where they would start to stagger, but they hadn’t sent any medical help. They had sent a self-important policeman. He drove towards us at over one hundred kilometres per hour, siren blaring, down the deserted highway leading to nowhere, and only just managed to stop his car in front of a group of men so indifferent by now that they hadn’t moved out of the way. He leaped out in a fury, sure of his Hungarian status and his power over the weak, waving his rubber baton and shouting while people stood in horror. I took a few pictures of him: the first Hungarian face seen by those arriving from the war, the cold face of a monster.

A quarter of a century ago the world celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall. I have framed fragments of it at home as a reminder of the breakthrough for humanity. Now, here we are, throwing up walls and fences globally at an almost unprecedented rate. Some are visible. Worse are the ones inside heads and hearts that divide “us” from “them”, as if “they” are somehow less deserving of a peaceful life.

All the barriers now being put in the way of the refugees trying to reach safety in Europe deeply shame this continent, one of the most privileged places on earth to live. The sight of small children clutching the hands of parents as they trudge along railway tracks in search of a safe haven carries echoes of the horrors of all the wars fought in Europe within living memory. The image of Aylan Kurdi’s small body slumped face down in the sand, washed up on a beach, heart-rending flotsam, shocked many into outpourings of sympathy and compassion. Compassion lies beyond empathy, in action, doing whatever possible to help end this suffering. It is the challenge facing every one of us in Europe now.

European Union

We got a Nobel Prize

for Peace. How nice. Finally

we can close our eyes.

Bicske

Because

it’s difficult to feel the edges to the words

‘refugee’

and

‘crisis’, because

these words stretch round the things’ outsides, until

we can’t see to the end of either’s fences,

we feel discomfort.

For us, discomfort is a hard feeling.

Almost as hard as hate.

Almost as hard as fear.

It is a word we can’t break out of.

Cover image by Judit Ferencz