This is a story about New York in the 1970s. A broken, genderfuck friendship story.

When I was fourteen years old and an aspiring writer, my best friend was a twenty-eight-year-old drag queen and performance artist named Stephen Varble. I was in the ninth grade at Brearley, an all-girls school on the Upper East Side, and at that point Stephen was really the only boy I knew. For almost three years, we explored the seedier undersides of the city; he introduced me to cocaine and kissing and to John Waters’ star Divine, and I provided him, grudgingly, with something approaching home. We charmed, wounded, infuriated each other, squabbled and made up, but even in our most exasperated moments, we each had this weird faith in our friendship as a kind of artistic endeavor: I interviewed Stephen about his work, recorded in my diary every conversation, every meeting; we wrote poems about each other; Stephen commissioned a photographer friend to make a film of the two of us, of which only two stills survive. He called me ‘Nenna Fiction’.

I went away to college, and stopped answering Stephen’s letters. He became a religious recluse, got Aids, and died; later he was forgotten because his art was so militantly ephemeral, and because most of the photographers who documented his performances also died of Aids and were forgotten. Now both he and they are being rediscovered, and the first museum show devoted to Stephen Varble’s work is opening in New York in September this year. It’s taken me forty-odd years to be able to begin thinking about this friendship, which is also a story about Aids, genderqueer art, and a city that not so long ago offered possibilities of wild, unsurveilled freedom and experimentation.

It’s Easter Sunday, Fifth Avenue. The year is 1975. By the seventies, the Easter Parade’s gone from being a society ritual – John D. Rockefeller walking his family to church – to carnival kitsch: couples wearing Easter bonnets the size of grand pianos, Latina triplets in hot-pink lace tap-dancing outside St Patrick’s.

My own Easter’s been – so far – pretty quiet. I’m cutting across Fifth Avenue at 59th, a pale baby-faced adolescent dressed in a sailor’s peacoat and white canvas Keds, on my way home from seeing Buñuel’s The Phantom of Liberty at the Paris. ( The Paris, cater-corner to the Plaza Hotel, had a side entrance you could sneak through if the movie was R-rated.)

I used to go to the movies a lot on my own – to Rogers and Astaire double bills at Theater 80 St Marks, to Truffaut movies at the Carnegie Hall Cinema, and to the Anthology Film Archives to see films by Jack Smith, who’d been a friend of my mother’s.

I did a lot of things by myself as a kid. There was some damage in me that meant I found other people’s company exhausting. I thought it was my business to be solitary, a watcher, that that was what writers were.

The Easter Parade is winding down, when I spot Him. Her. Them. The Apparition. The Apparition is a bearded young man, lunar-white except for the lavender-and-pink eye makeup. He’s wearing a headdress of half-burnt wooden matches crowned by a souvenir matador and bull, a gown made of golden Seagram’s V.O. labels, and a pair of black evening pumps. He is on the arm of a mustachioed cowboy in black leather, and he’s performing this silent movie pantomime: sidle, shimmy, eyelash flutter, ogle. A small crowd surrounds him.

The thing is, I know him already. I’d clocked the Apparition a month earlier at a Tibetan evening at St Mark’s Church-In-The-Bowery, drifting up the aisle in a white wool cassock, with a shredded paperback of the novel Forever Amber strapped open across his forehead like an Orthodox Jew’s tefillin, its pages fluttering. Odder still, I’m carrying a photo of him in my wallet, clipped from the SoHo Weekly News. I don’t know his name, but already he’s in there with my hottest fetishes, and I know we belong together in some way.

I pass the leather cowboy my newspaper clipping, and now the Apparition’s doing her tricks just for me. ‘What’s your name, little girl?’ she whispers in this Southern drawl. She’s surprised to see a kid like me at the Easter Parade. ‘It used to be real festive, but now it’s all RIFF RAFF!’ – her voice hiking up to a gargled shriek.

She’s right. The mood’s turned hostile – a gang of Puerto Rican men has moved in, catcalling, baiting. A soda can is thrown, just misses. The two policemen watching don’t do a thing. This random violence from strangers will become familiar to me, tripping along the streets of Lower Manhattan, the Rockaways – worst of all, Staten Island – arm in arm with a bearded man dressed in ballgowns made of garbage: it’s part of the perspectival whiplash entailed when a child of privilege falls in with someone from the wrong side of the socio-sexual tracks.

The Apparition, unfazed, bats her eyelashes at this jeering circle of males, except that suddenly she and the cowboy have disappeared down a subway entrance, and me along with them. We’re on a downtown train, and the Apparition is taking me home to his.

Stephen Varble had been in New York six years when we met. He was born in 1946 in Owensboro, Kentucky. There are still a lot of Varbles in Owensboro. Judging by YouTube postings, if your name is Varble, you are most likely to seek fame as an evangelical preacher or a bluegrass banjo player. (There is also a fifty-one-minute film on YouTube of Stephen dancing in the disco Hurrah, naked beneath a costume made of bead curtains and a life preserver stolen from the Staten Island Ferry.)

Stephen’s family were stalwarts of the Audubon Church of the Nazarene, his father had some kind of real-estate business, and Stephen was a mamma’s boy, but he must have known pretty early he had to hightail it to a big city. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Kentucky, and arrived in New York ‘with seven dollars and a pretty face’‚ he later told me. He waited tables at the ice-cream parlor Serendipity, and supposedly was fired for performing stripteases for the customers, but also got his master’s in film from Columbia. Straightaway, he encountered Jack Smith, another bearded costume queen whose baroque bacchanalia shot on damaged film stock went right into Stephen’s bloodstream; he performed in Fluxus happenings; his plays were produced at Lincoln Center and La MaMa. These are the building blocks of a mainstream arts career, but already there was something virulently anti-institutional in Stephen’s ethic that made him sabotage any glimmer of even supposedly ‘indie’ success.

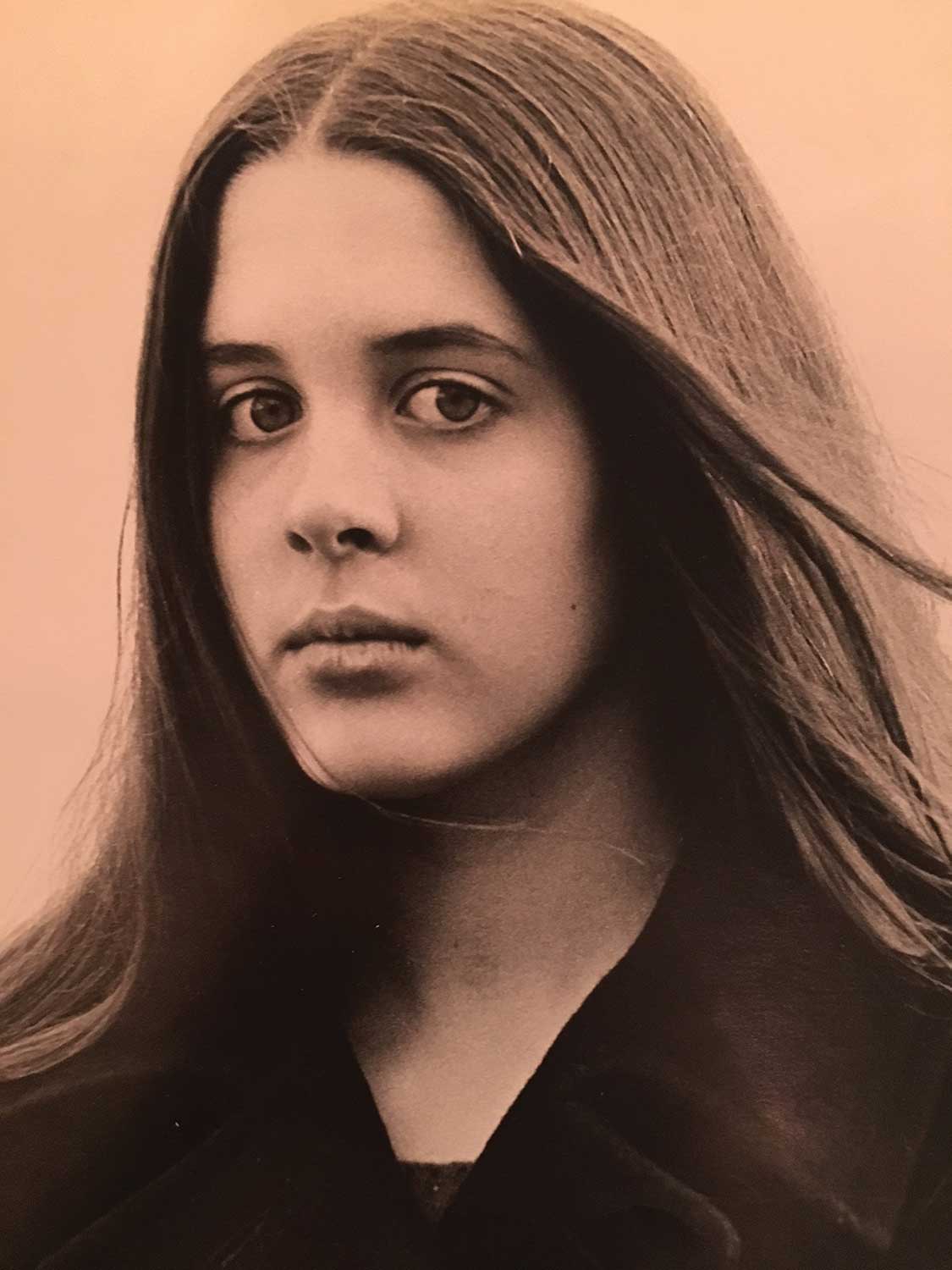

Fernanda Eberstadt, two months before she met Stephen Varble, 1975

By the time we met in the spring of 1975, Stephen was practicing what he described as Gutter Art: street performances in costumes concocted from materials he found in the dumpster. Sometimes these performances involved corralling passersby into guerrilla ‘tours’ of the SoHo galleries; sometimes he had himself driven around town by his patron Morihito Miyazaki in a Rolls-Royce, wearing an Elizabethan-style hooped skirt constructed from egg cartons, and stopping outside strategic sites – the Metropolitan Museum, say – to wash a stack of dishes in the gutter. In Stephen’s most famous action, staged a year after we met, he flounced into a branch of Chemical Bank, wearing a gown made of dollar bills, with breasts formed by twin condoms filled with fake blood. Shrieking that someone had forged a million-dollar check in his name and he wanted the money back ‘Now! Now! Now!’, Stephen exploded his condom-breasts like a gender jihadi and began writing checks with the blood.

What do you do with an artist whose politics are expressed with such whimsical coquettishness that you could mistake his assault on capitalism and the art industry for mere camp? This was class warfare, though Stephen would say that his dispossessed were the natural aristocrats dismayed by the tackiness of contemporary commerce. Like Diogenes, the ancient Greek philosopher who is the godfather of political street art, Stephen had come to debase the currency.

We are sitting on the M train, me, Stephen in his golden Easter Parade dress, and the leather-clad cowboy, headed to Stephen’s apartment on the Lower East Side. The cowboy, Stephen’s off-and-on lover, is called Robert Savage, and he’s shy to the point of mutism. He’s an experimental composer who works in a jewelry store ‘to satisfy his insatiable passion for opals’, Stephen explains. ‘He’s kinda mystical, but we don’t have sex anymore because he does awful things to himself: he’s a self-castrator. He carries on these long, secret blood rituals – draining his veins and sticking things up his urethra to make the blood gush out. He’s always getting hospitalized, with blood streaming.’ Leaning closer, Stephen confides, ‘He can’t even beat off anymore!’

Robert, silent, grinds the heels of his black policeman shoes into the subway-car flooring.

I look at Robert sideways with an unsettled kind of fellow feeling. Sex scares me rigid. Soon as my child’s body sprouted unwanted breasts, middle-aged men had started rubbing themselves against me on buses, murmuring obscenities. Home is no refuge: since I was little, my mother’s bedtime stories have been about the different things she likes to get up to with her boyfriends.

My reaction to all this sexual terror has been to become obsessed with gay male strangers, whom I stalk at a safe distance. Only by keeping everything in my head, with multiple barriers against consummation, can I feel some control. It will take me some time to realize that I’m not just attracted to gay men, I want to be one. I’ve gone from dreaming myself Tom Sawyer to dreaming myself Tom of Finland.

Today, my adolescent self might be tempted to identify as genderqueer – Stephen, I am guessing, would have found the whole notion of ‘identifying’ drearily bureaucratic – but back in 1975, this attraction to an outlaw tribe from which I was excluded felt somewhere between tag-along embarrassing and insane.

No more insane, though, than wanting to drain your own blood or dress up in garbage.

Stephen’s studio, above a Chinese takeout on Delancey Street, resembles a backstage costume room, with wardrobe racks and a dressmaker’s dummy and a giant, pink satin mattress on the floor. Stephen and Robert and I roll all over it and tickle each other with pink feather-puff pillows, till Stephen announces, ‘I’m so ravenous I could eat this pillow and lick my fingers afterwards.’ He’s biting each knuckle hard in quick succession – ‘That keeps them kinda staring and agonized-looking’ – but his self-cannibalism is also hunger. He’s often hungry, and mostly I’m too well fed myself to respond to the hints.

Luckily, tonight my weekly allowance is still intact, so Robert and I watch Stephen change to a pair of Levi’s and a plaid flannel shirt – he’s constantly code-switching from Marie Debris, his costume-queen alter ego, to butch-er styles of queerness – and I treat him and Robert to dinner at the Star of Bengal, which is Stephen’s ‘favorite place in the wo-orld because they serve pomegranate cocktails that make you scream’, he says, letting out a ladylike caterwaul. I am quietly soaring, it’s one of those moments when a kid thinks: my real life, the life I’ve always dreamed of, has just begun.

In the spring of 2016, I came upon a Peter Hujar photograph of Stephen from his Chemical Bank action. Eyes half closed in swooning bliss, luscious lips parted in a roguish smile, he brandishes a check made out to Peter Hujar for ‘zero million dollars’.

My heart crashed.

It had been decades since I’d thought of Stephen. The last time we met, after a long break, was in 1982, and ever since, as the Aids epidemic raged and gentrification erased all his old habitats, I’d blanked him from my consciousness. Wondering what had happened to Stephen would have meant admitting that he must have died of Aids – why else wouldn’t I have heard from him in all these years?

I googled ‘Stephen Varble’ and waited.

There’s a hideous stomach drop when you google an old friend, and no entries turn up: an absence that tells you this person had stopped existing by the time the web came along.

I tried again, and this time found a reference to ‘the now forgotten performance artist Stephen Varble, an early Aids victim’. His dates: 1946 –1984.

The knowledge that I’d stayed away from my friend when he was sick and dying was terrible.

But Stephen Varble isn’t forgotten.

Over the next few months, I keep trawling, and finally a live item surfaces: David Getsy, a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, is doing research on Stephen Varble and genderqueer performance in the seventies. He’s giving lectures, organizing an exhibition. I contact Getsy. The material record is scarce, he tells me: Stephen’s last surviving costume, which had been stored in a friend’s basement, was destroyed in Hurricane Sandy. I unearth my long-buried trove of Varble memorabilia, send Getsy scans of letters, photos, homemade press releases; Getsy mails me two stills from my vanished film with Stephen.

Sign in to Granta.com.