Americans are taught that railroad magnates Leland Stanford and Collis Huntington ‘built’ California – their names adorn the state’s most prominent universities, libraries, and parks – but thanks to fiction additional facts arise: they belonged to a cadre of robber barons called The Big Four who defrauded public trust, bribed senators and judges and exploited poor immigrant labourers without qualm. When history chronicles its unfettered capitalists, these two will make Donald Trump look like small change.

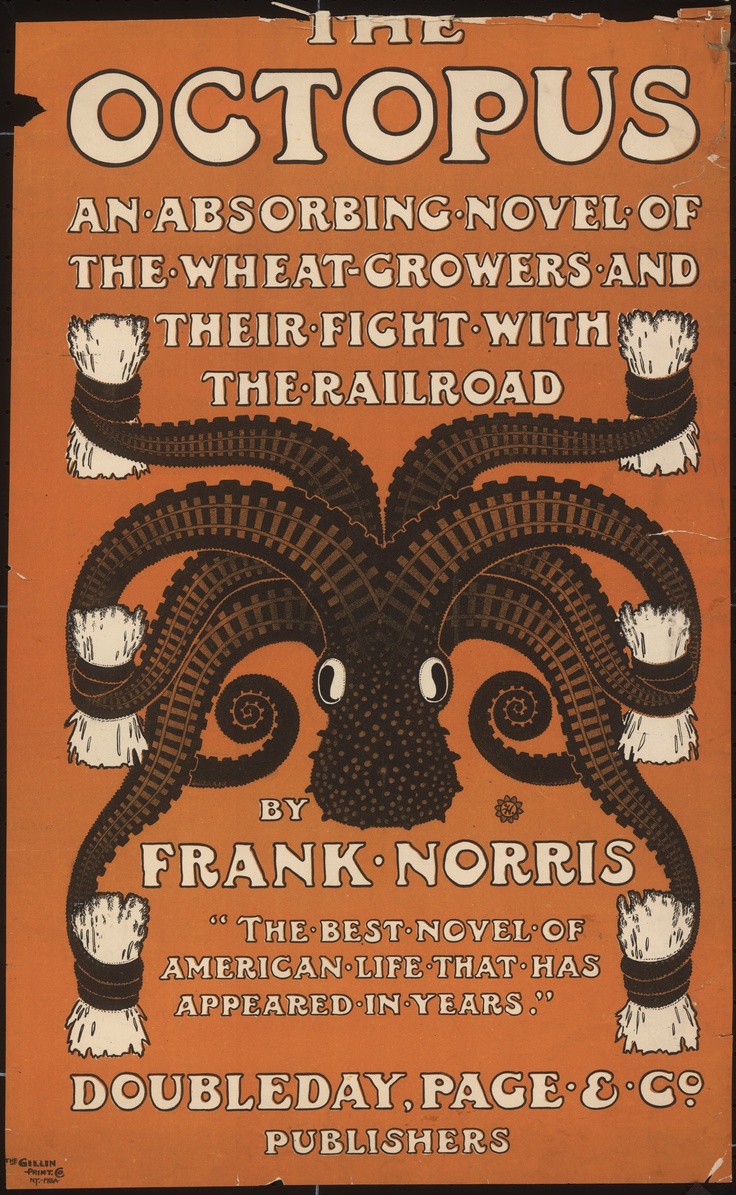

In Frank Norris’s sweeping saga The Octopus, the machinations behind America’s ‘transcontinental’ railway (now Union Pacific) are laid bare. The novel is a white-knuckler of the first order. It deserves to be made into a film. (Norris’s debut novel McTeague was adapted into Erich von Stroheim’s epic silent Greed.) The Octopus turns on a love story between splenetic Buck Annixter and rancher’s daughter Hilma Tree. Behind them stretch their families’ legacies of hard labour – dairy farms, pear orchards, vast wheat fields ‘quivering and shimmering under the sun’s red eye’. Their community includes Scots engineers, German hop growers, Italian fruit merchants and Chinese workers hired by the railroad to dig its ditches and lay its tracks. The Big Four are never named, but their eyes peer down from the head of their ever-expanding beast. Inside courthouses, their schemes are put in place – shipping monopolies and tariffs established, brokers hired to engage straw buyers at public auctions.

The railroad’s tentacles grasped the largest mass migration in American history. Following the 1848 discovery of gold, the population of San Francisco soared from 1,000 to 20,000 in two years. By the mid-1850s there were 300,000 new arrivals, many of whom came on the promise of land in exchange for labour. (The novel was inspired by a massacre: after dangling property ownership for those in its path, the railroad, in effect, sold the best land to itself, culminating in a deadly showdown between gunmen deputised as US Marshalls and duped sharecroppers still clinging to bogus mortgage bonds. The Big Four would make over $700 million in the affair.)

A former newspaper correspondent to Cuba and South Africa, Norris developed his sentimental, naturalistic style from Zola – and in turn influenced novelists Upton Sinclair and John Steinbeck. He died suddenly in his bath at thirty-two from peritonitis and is now enshrined in San Francisco, where his face features on post office murals and a city street bears his name. In the UK, Norris is practically unknown. His novels can drift into heavy-handed mysticism, but in their great tenderness for immigrants they illuminate the plight of those who might otherwise be forgotten.

In 1994, while a jobbing actor in Hollywood, I was so taken by The Octopus that I wrote a full-length screenplay adaptation. The process taught me about story structure, dialogue, and the importance of foregrounding characters by their larger canvases. Too young to be apprehensive, I shopped my script around movie studios, cocktail parties and tennis clubs – only to join the numberless Californians with undeveloped screenplays. It was one of my first pieces of creative writing.