The Emily Dickinson Series

Janet Malcolm

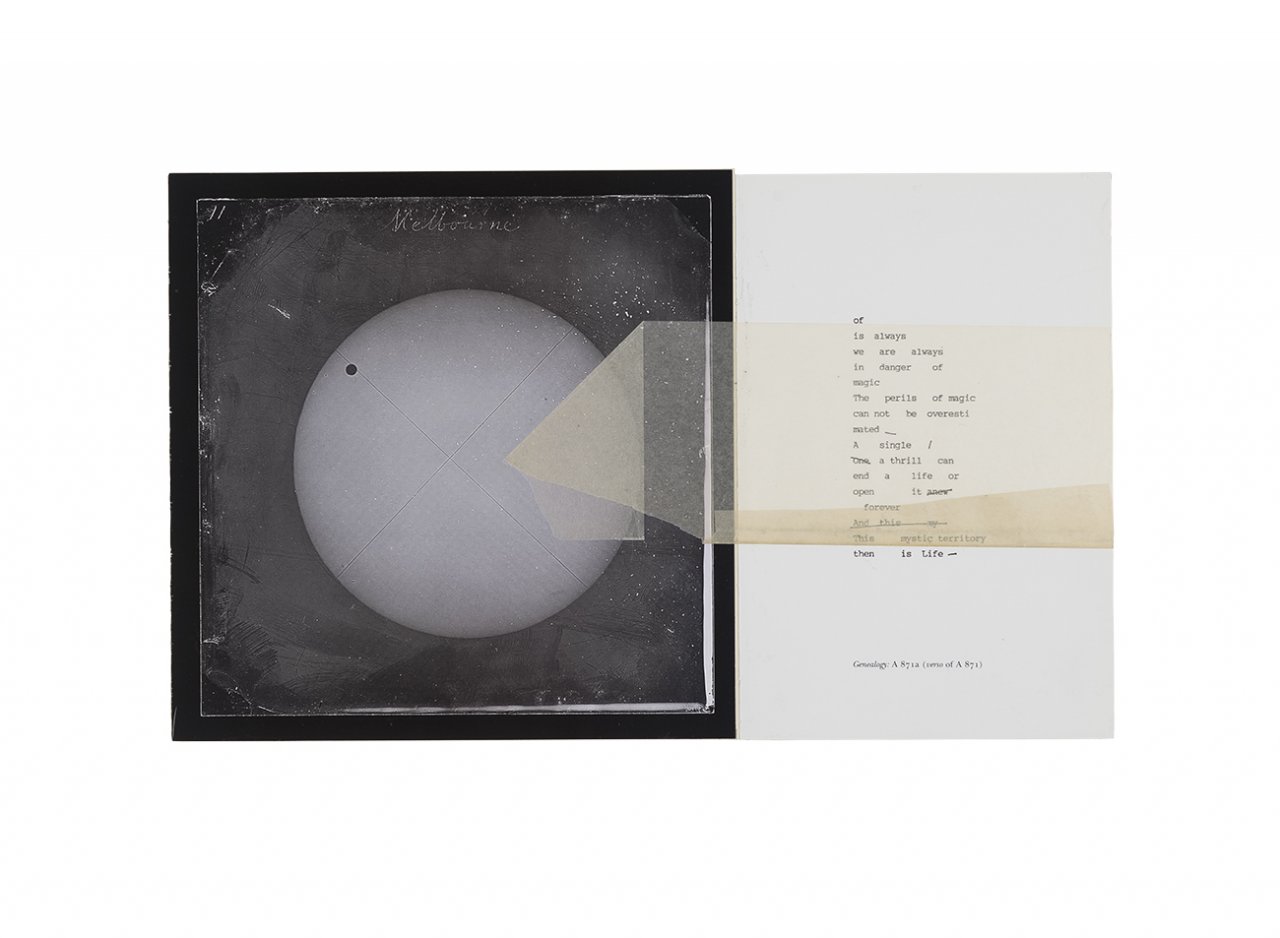

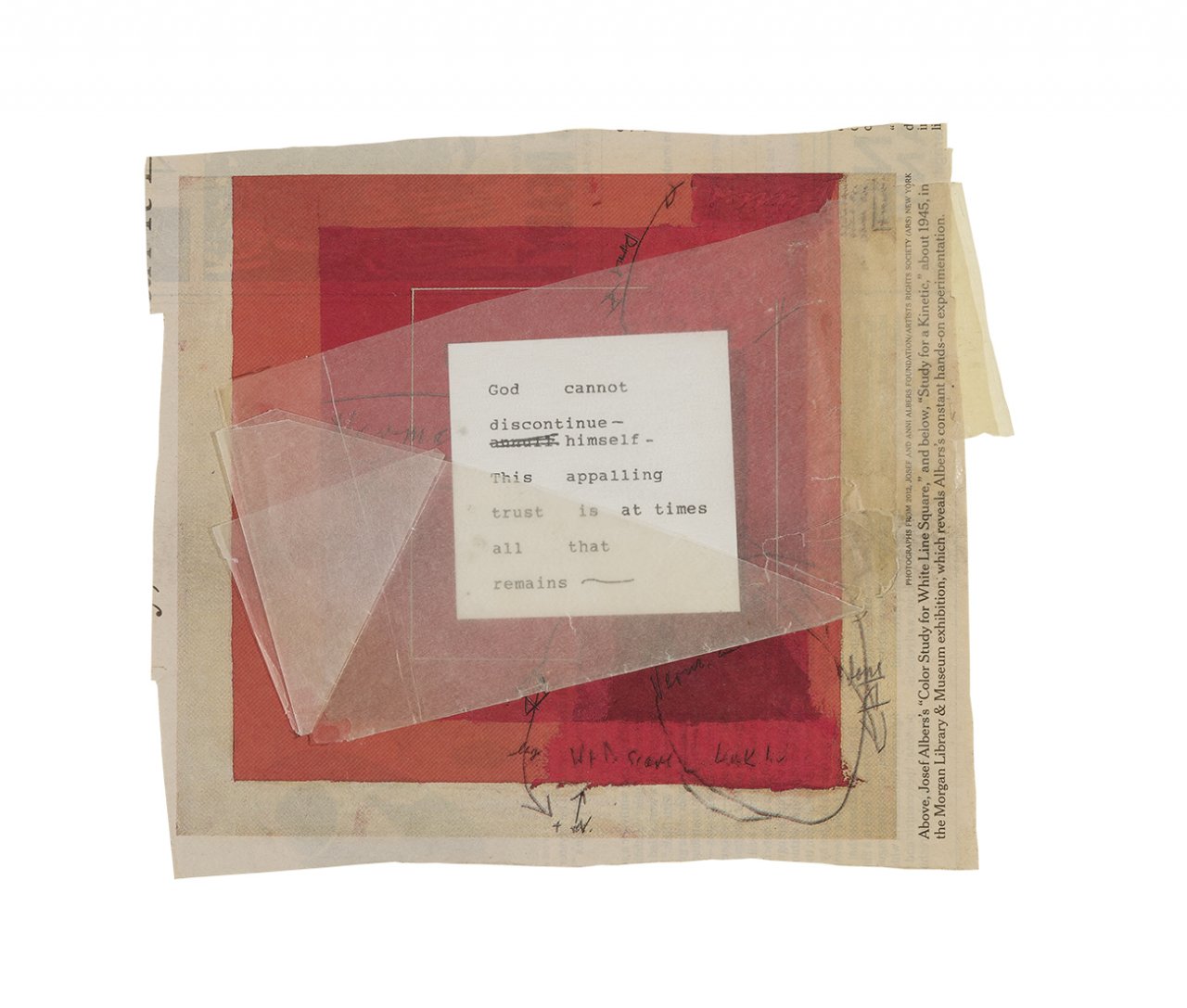

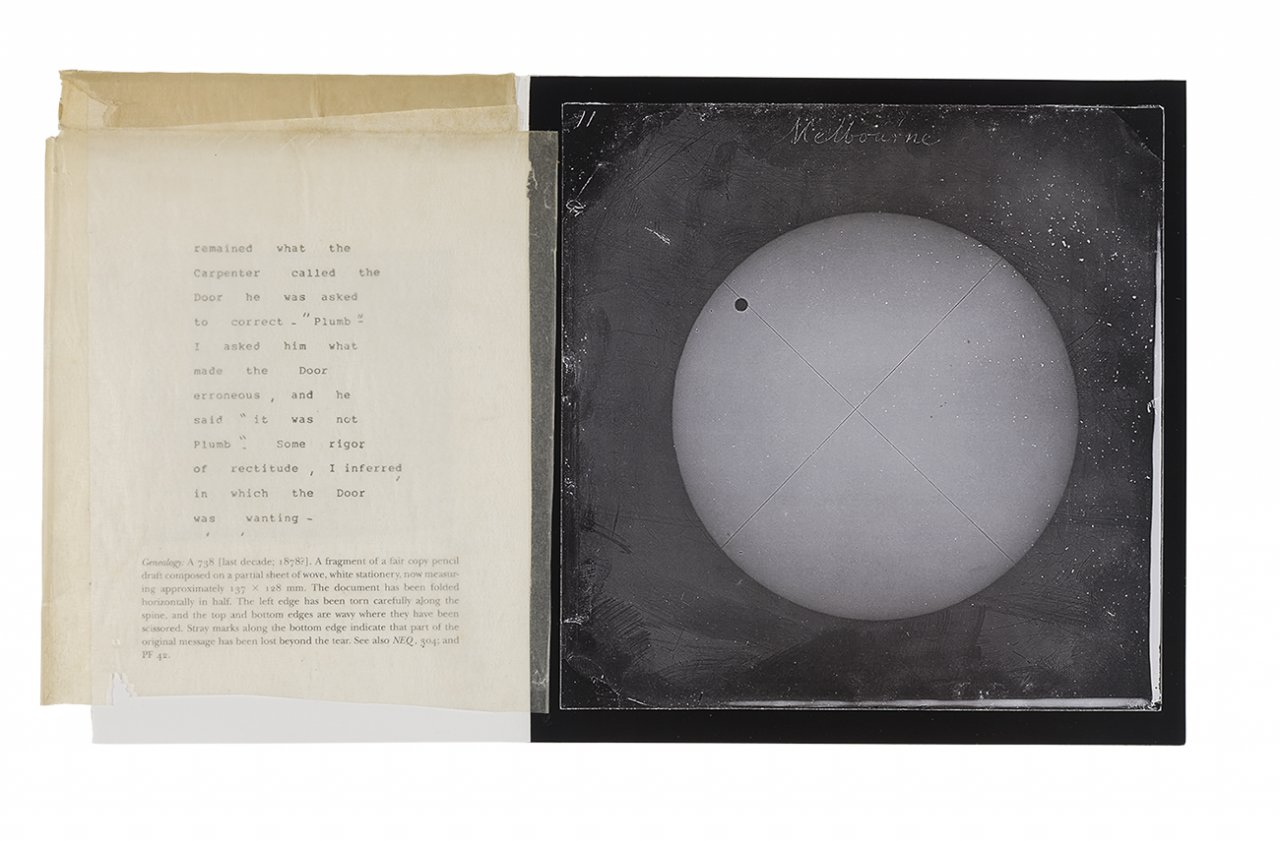

When I first opened Marta Werner’s Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios I felt a shiver of interest and desire such as one feels in an expensive shop at the sight of an object of particular beauty and rarity. I was drawn to the book’s right-hand pages on which typewritten words appeared – words that were wild and strange, and typing that evoked the world of the early-twentieth-century avant-garde. These were Marta Werner’s transcriptions of scraps of handwritten prose by Emily Dickinson, discovered after her death. The scraps themselves were reproduced in facsimile opposite the typed transcripts.

The book belonged to my friend Sharon Cameron, a professor and critic and the author of two books on Emily Dickinson that are considered classics in the field. I was at her apartment. She had shown me the book – I forget for what reason – and I asked if I could cut out some of the right-hand pages to put into collages. She looked at me in horror and said, ‘Certainly not.’

I tried to buy the book on Amazon and found it was out of print, and couldn’t find it anywhere else. Sharon suggested I write to Marta Werner:

18 September 2012

Dear Marta Werner,

I have been trying to purchase a copy of your wonderful book Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios, and have had no success. My friend Sharon Cameron suggested I write to you on the off chance that you had an extra copy I could buy from you, or that you could direct me to a source.

With thanks and best wishes,

Janet Malcolm

~

Dear Janet Malcolm,

How extremely kind of you to write!

It’s rather strange, I suppose, but I have only one copy of the book. I believe my mother has one, too, though, so since there’s one floating about the family somewhere, I’d be happy to send you my copy. I certainly don’t want anything for it.

If you’d accept my copy, I’d be delighted to send it. It seems to belong to another part of my life – I hope I learned from it!

All my best,

Marta

~

19 September 2012

Dear Marta,

I cannot tell you how moved I am by your offer to give me your only copy of the book. Your generosity is staggering. Of course I accept with enormous pleasure and gratitude. May I, in inadequate return, send you a copy of my book Burdock, a collection of photographs of burdock leaves that grew in the New England countryside? If so, would you send me your mail address? My address is [ . . . ].

With huge thanks and all best wishes,

Janet

~

Dear Janet,

Thank you so much for accepting the book. It is a small thing, after all, and I fear you will definitely lose in this trade. Please don’t regret it too deeply!

Of course I would be delighted to have Burdock – and it could not come at a better time. I am just starting work on the field notebooks of a rather obscure early-twentieth-century naturalist – Cordelia Stanwood – and your photographs – and especially your essay – will press me forward through uncertain beginnings. My address is [ . . . ].

It seems somehow rude, or cliché, or some combination of both, to tell you how much I admire your work. But it is true, so I’ll say it anyway, and hope I don’t embarrass you.

Gratefully,

Marta

~

Dear Marta,

I’m so glad that you know my work and like it. If there is any other book (or books) of mine I could send along with Burdock, would you let me know?

All my best,

Janet

~

20 September 2012

Dear Janet,

How generous! But I think I have everything!

Open Folios is winging its way to you.

Thank you for taking it . . .

Marta

~

25 September 2012

Dear Janet,

Burdock is here. It is beautiful.

It came at a strange time. My mother is very ill, and when I look at the leaves – pristine and ravaged at once – I think of her.

She would love them, too, without making the comparison. Thank you so much.

All my best,

Marta

~

26 September 2012

Dear Marta,

Your remarkable book has arrived, with your lovely inscription, and, again, I am so very grateful and cannot thank you enough. I am curious about the transcriptions. They look as if they were done on various old typewriters. Did you do them? I am very sorry to hear about your mother’s illness. How hard this must be for you. I send all my best wishes for her recovery.

Janet

~

27 September 2012

Dear Janet,

I’m so glad the book arrived. The transcriptions are indeed my own – and what a trial! I was working on the book so many years ago – in the early 1990s – and so the possibilities (technologically speaking) were rather limited. And, beyond this problem, far beyond it, was my great uncertainty about what an ‘ideal’ transcript of a Dickinson poem would look like. In the end, I decided I wanted to do a few seemingly contradictory things: call attention to the ‘alienness’ of the transcript – its distance, temporal and iconic, etc. – from the manuscript; show and partly enact the conflict between the regularity of type (or typesetting) and the singularity of the hand; and break down distinctions between prose and verse by insisting on following Dickinson’s physical line breaks. I’m not at all sure these intentions – such as they were – translate to readers, but this was what was in my mind. And I think the spirit of Melville was working in all this too – and a story I heard about Melville insisting on always adding the punctuation to those of his works transcribed by others – his sister & wife. In transcribing Dickinson, the excessiveness of certain letters and marks fought and won over the regularizing typewriter.

And yes, initially I did do the transcriptions on typewriters. My grandfather had an amazing (if worthless!) collection of typewriters, which I commandeered for the occasion. Now I am quite sure I would proceed differently! But honestly, I still do not know exactly how. [ . . . ]

Thank you very much for the good thoughts about my mother. When I see her in a few weeks, I will bring Burdock to show her. I am sure she will be moved.

At the end of the book, you mention a particular way in which the original photographs were transformed. Do these photographs in the book look so very different from your originals?

I am sure you have seen Dickinson’s herbarium?

I have a question about an exquisite sentence in your introduction – something about the ongoing project of decontextualization. But I will have to ask it later, since I don’t have the sentence before me. When I read it, it struck me as related to the whole problem (or interest!) of the transcript, and I wanted to pursue it further.

About a year before my father died, we took up the habit – he started it – of sending each other lists of the numbers of Dickinson poems we liked.We did not comment at all on the selections – simply exchanged them every few weeks over the course of several months. The experience was slightly uncanny, and it struck me last night that one could do such a thing with the burdock leaves. That is, that they might be exchanged as messages. The more I look at them, the more they seem to say – or at least the more I talk to myself.

Thank you so much.

Marta

~

29 September 2012

Dear Marta,

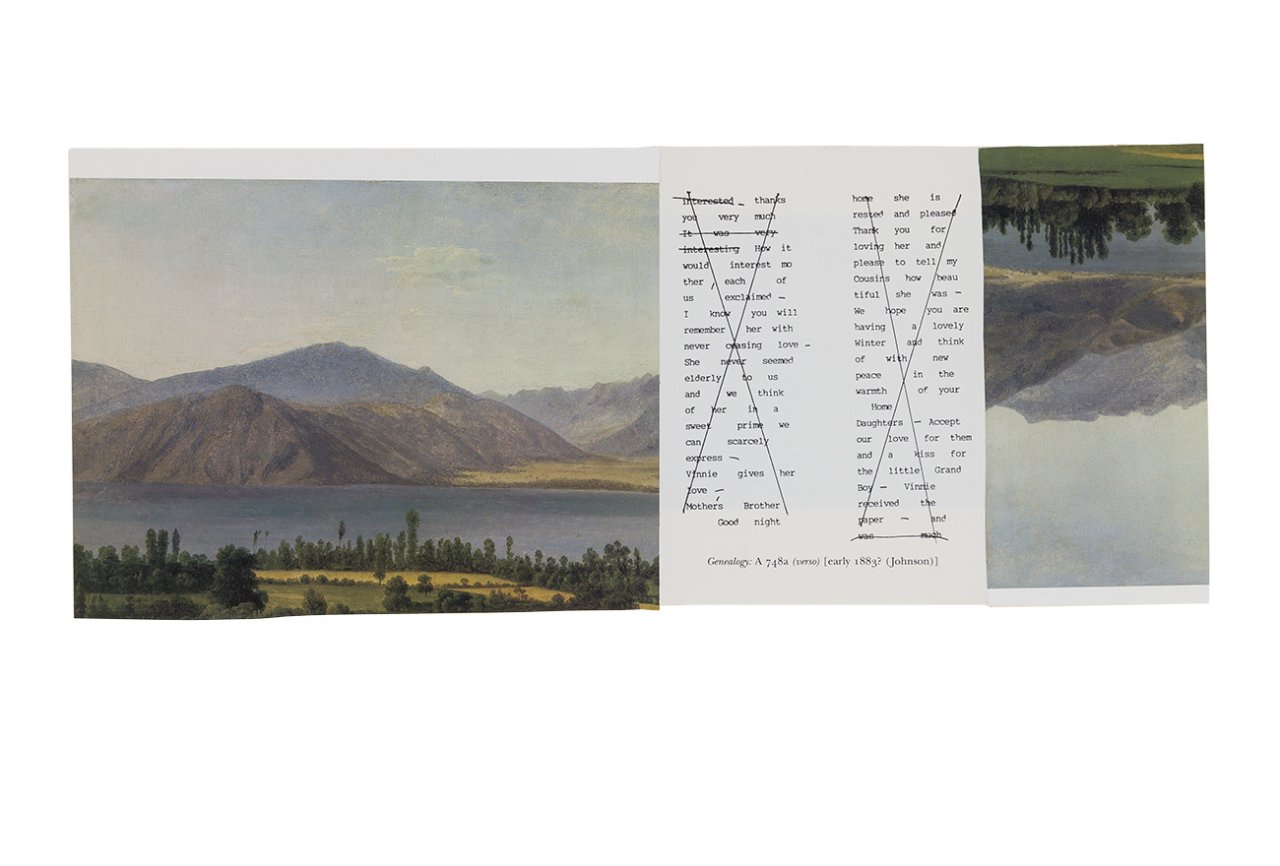

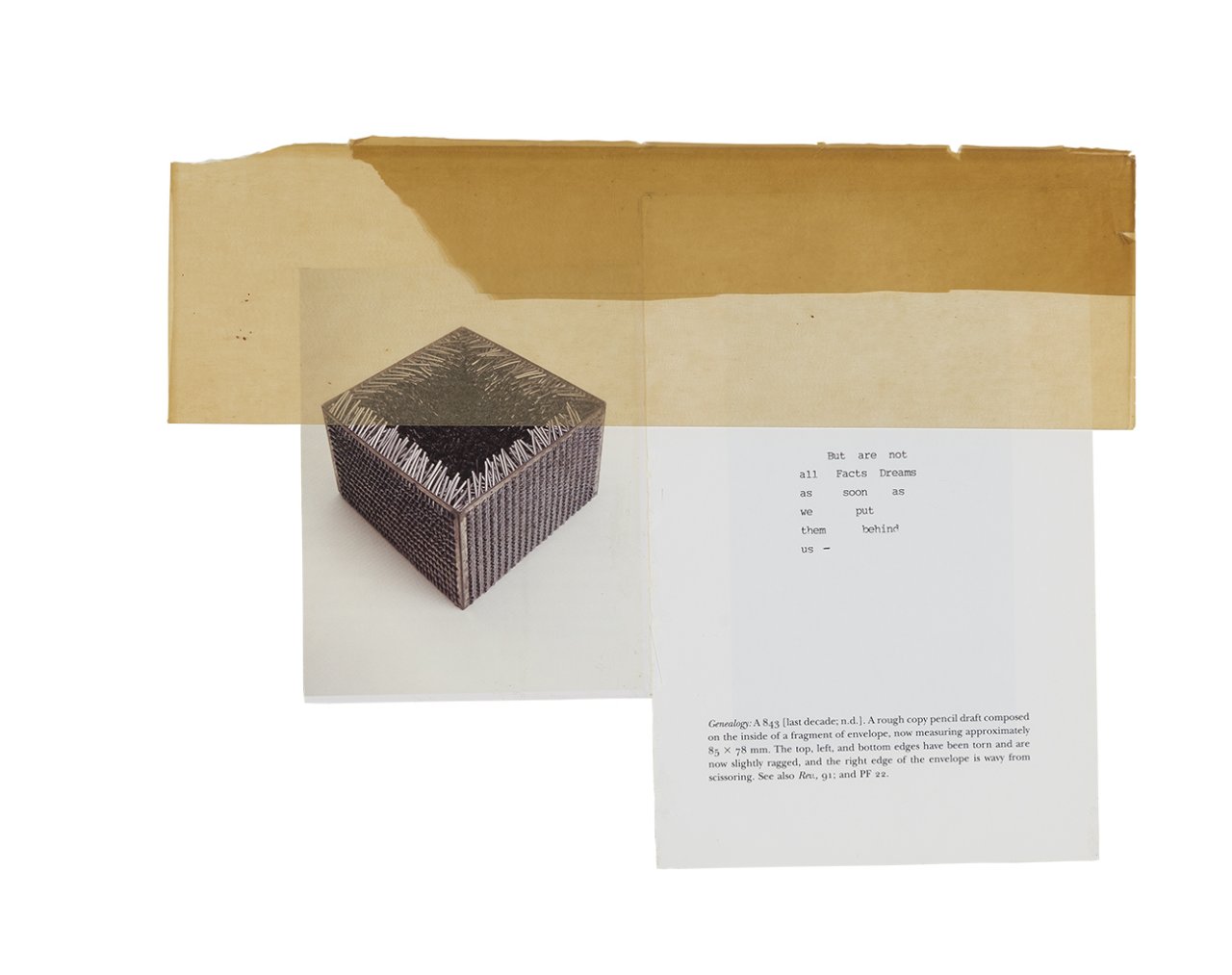

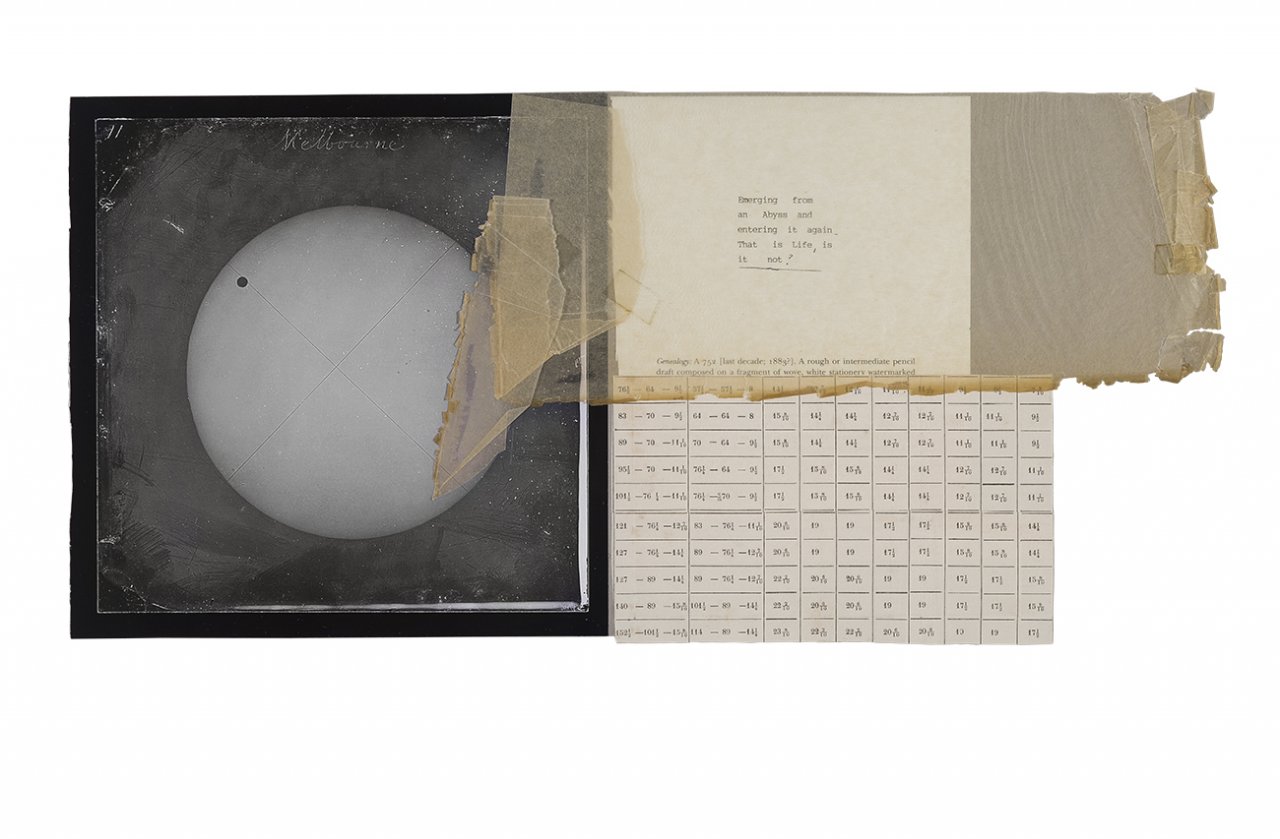

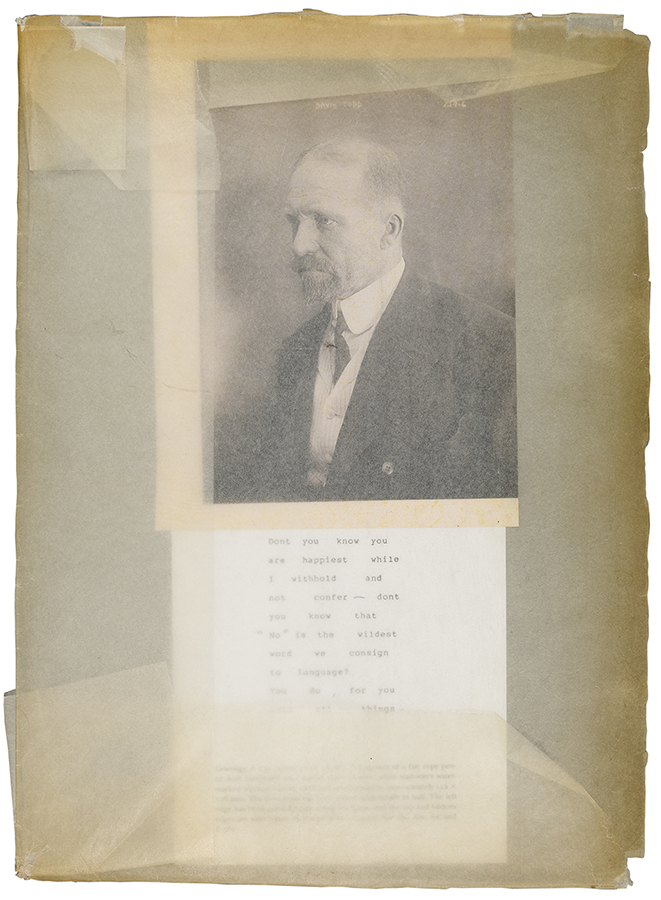

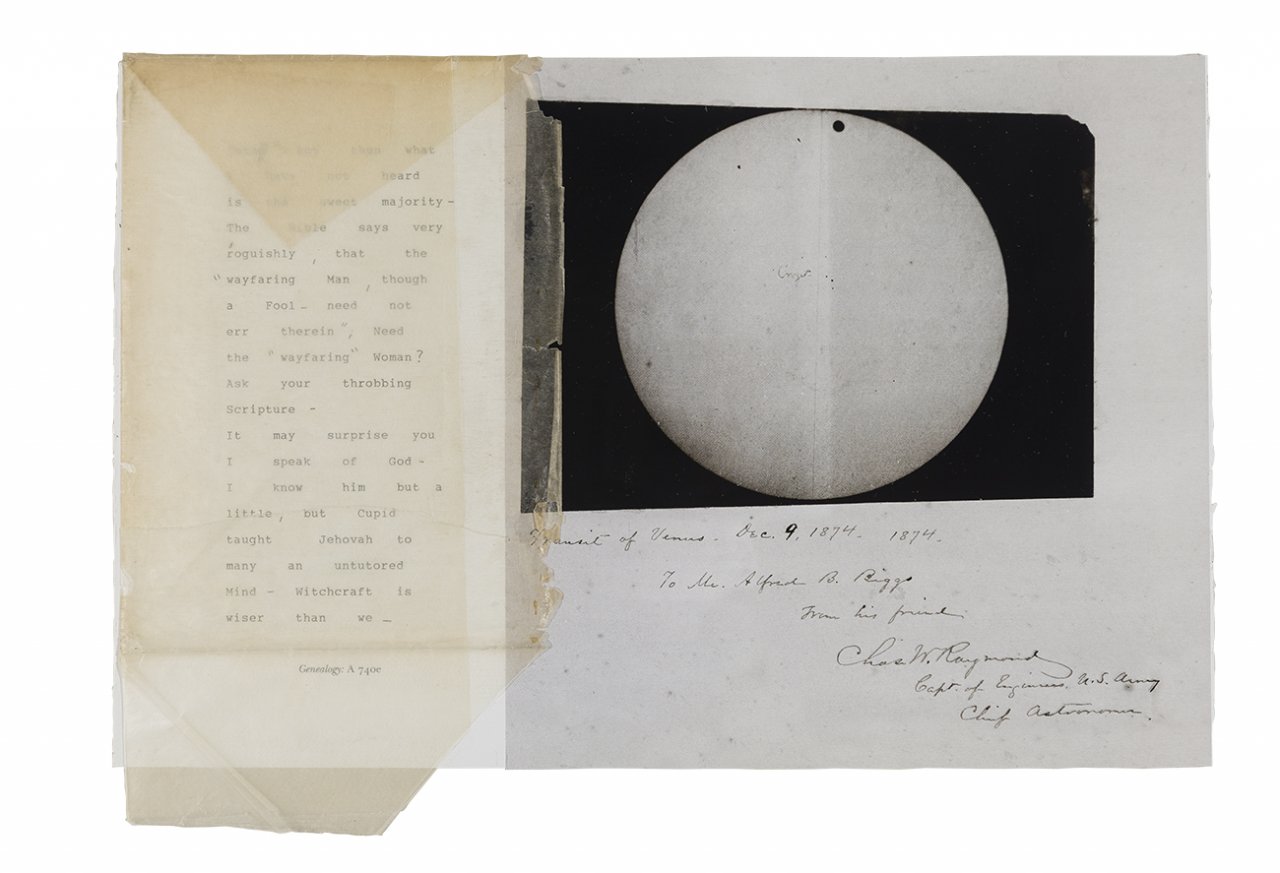

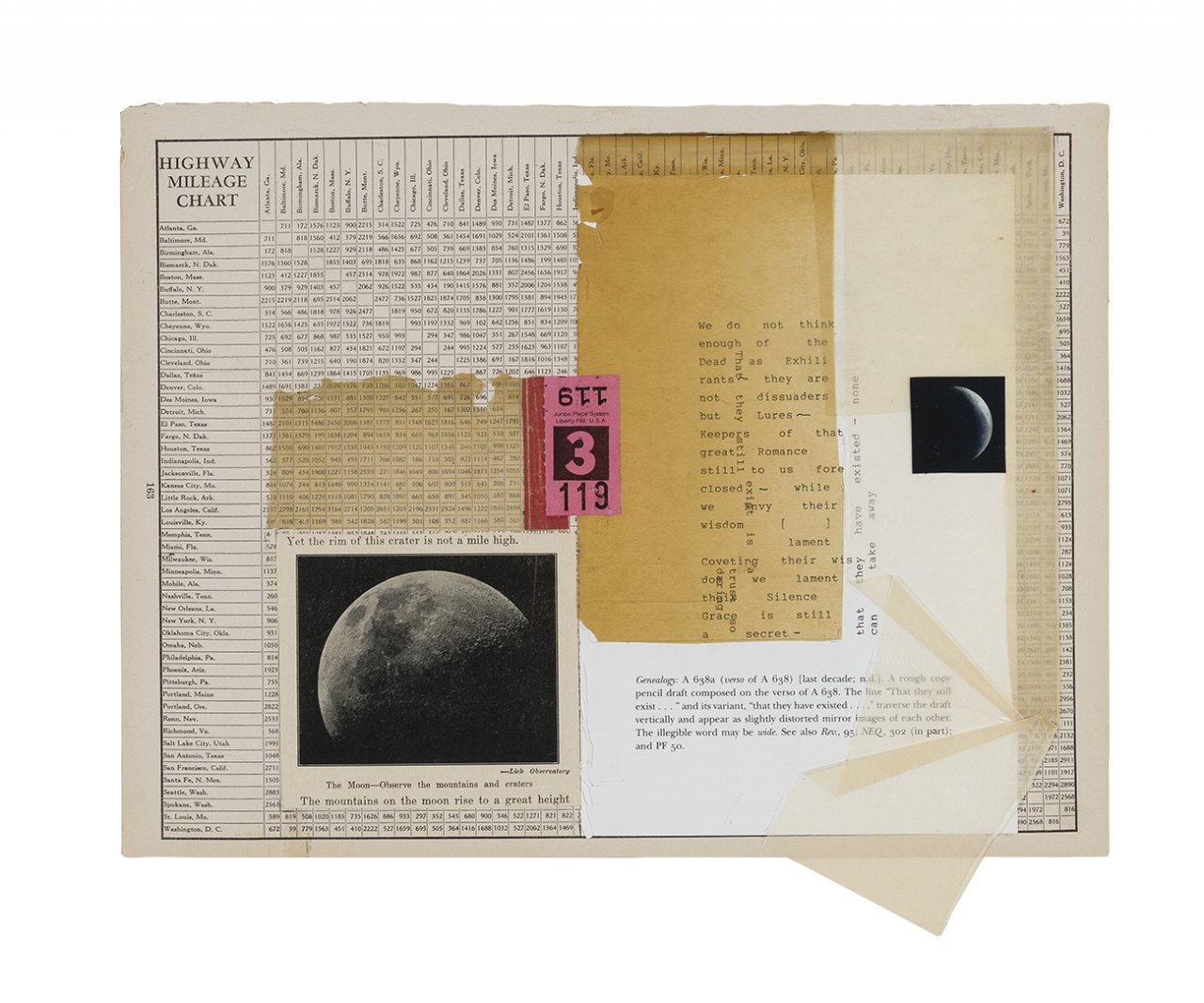

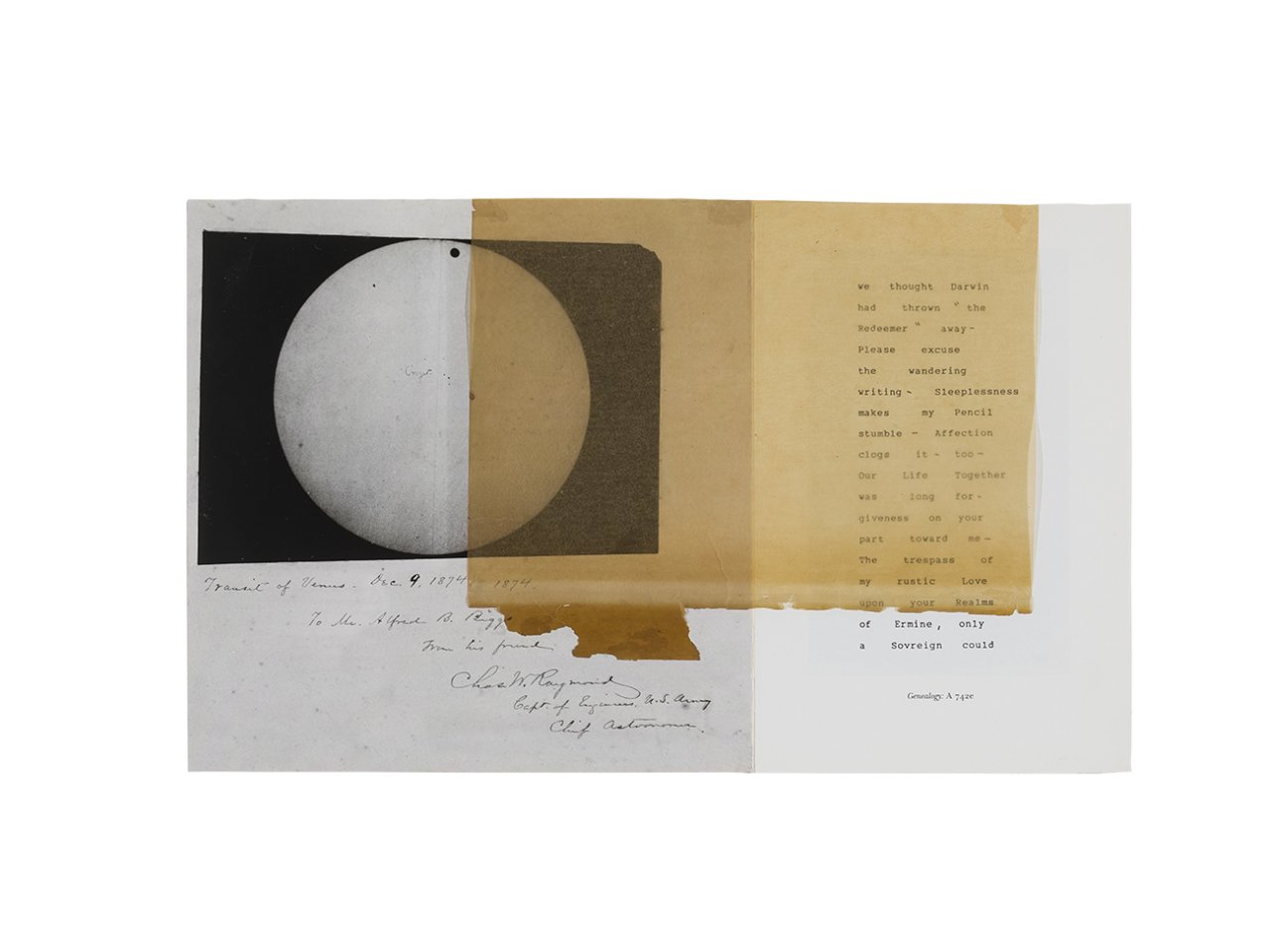

Many things in your letter – especially the mention of decontextualization – tell me that the time has come to tell you of the special reason why I wanted a copy of your book – namely, to cut some pages out of it and put them into collages. When I saw the book at Sharon Cameron’s house, this desire formed itself in my mind – I began to ‘see’ the collages. It was the typewritten transcriptions rather than the handwritten originals that stirred my imagination.The series I want to make will also use images and charts from astronomical texts. Before starting the ‘cutting’ and ‘scissoring’ (the words leaped out of your text) of your precious only copy, I want to have your permission to do so. I will completely understand if you would prefer I not do so, and will continue my search for another copy.

The way the burdock photographs are printed makes them softer-edged and more painterly. The prints themselves are much better than the reproductions in the book. If you ever come to New York, I would be happy to show the prints to you. Some are at the Lori Bookstein Fine Art and the Davis & Langdale galleries and others are under my bed.

Your use of the word uncanny resonates with me. Doesn’t it apply to our encounter?

All my best,

Janet

~

Dear Janet,

Oh but of course – cut away! I can think of no better fate for the pages of this last copy of my first book than to become collages made by your hands. And to have as company astronomical texts and charts – that is perfectly lovely. There is one – I think it’s A 742 – which is very torn and cut, I wonder if you will be drawn to it . . . And another – I think A 757? – where one word, ‘Last’, is written upside down and under other text. The word ‘Last’ is written in a beautiful, magnified fair-copy hand, the text that covers it is in the small, contracted hand of the working drafts. I wonder so much which ones will summon you. I only wish I had the original typescripts to send you. I moved several times since making them and, each time, things vanished, as they do. I shall search again, and if I find them, I will send them on to you – if only as curiosities.

I would love to see the burdock prints, in the galleries and under the bed, though I would not want to put you to any trouble!

As for uncanny encounters – yes – this meeting between us is as you say. And I value it all the more for the attending strangeness. There is not enough of this in correspondences – or friendships.

Gratefully,

Marta

~

30 September 2012

Dear Marta,

I am so happy that my project has your blessing, and will start work on it today. I will let you know which fragments I ‘appropriate’ as it’s called. The book is in my studio and I am about to go out and buy fresh glue.

With many, many thanks again,

Janet

Images courtesy of Janet Malcolm and Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York. Photos by Etienne Frossard, New York.

Janet Malcolm’s In the Freud Archives is available now from Granta Books.