Adrian Tomine is an artist and illustrator. He is most well-known for his New Yorker covers and the Optic Nerve comic series. His artwork has illustrated album covers by Yo La Tengo and DVDs for the films of Yasujirō Ozu. Here he talks to Francisco Vilhena about his work, unresolved endings and prank calls.

How did you start doing covers for the New Yorker?

It sounds improbable (even to me), but it was as simple as walking into the New Yorker offices and dropping off some samples of my work. Well, actually, that’s how I started doing illustrations for the interior of the magazine. An art director named Chris Curry apparently saw those samples and gave me a call. Then after doing stuff for the inside of the magazine for a few years, Françoise Mouly (the art editor who’s in charge of the covers) reached out to me about submitting some ideas for the cover, and then kind of held my hand through that process. I really owe so much to both Chris and Françoise.

I should also say that this all happened in a pre-9/11, pre-Internet world, so I’m sure that some random kid with a portfolio couldn’t just walk past security now, and that probably most submissions are now done electronically.

Can you tell me a little bit about the creative process behind your work?

When I’m working on my own comics, there’s really no set process that I rely on. The book that I’m working on now is comprised of a bunch of short stories, and I intentionally approached each story in a different way. I suppose the one common thread through all the different ways of working that I’ve tried is that I spend a long time thinking about a story before I ever put pen to paper. In some cases, I’m talking about years. And it’s just sort of always on my brain, so I’ll think about it as I’m going to sleep or when I’m waiting for the subway or whatever. A lot of interesting things develop when you sit with an idea for a long time. And the flip side of that is that a lot of different interesting things spontaneously pop up once I’m actually drawing the story . . . things that never occurred to me when I was just thinking about it. So I feel like I’m always trying to get the best ideas from those two disparate parts of the process and integrate them into the story.

You’ve worked on several different mediums, from album covers to magazine illustrations to graphic novels. Where would you say your influences stem from, are they strictly visual?

I wouldn’t say strictly visual, no. I’ve learned a lot of tangible, practical things from studying all kinds of things: comics, illustration, movies, prose, etc. But I think I’ve learned more from just hanging around creative people and talking to them and learning from their example.

Could you give some examples?

I suppose I’m talking about the kind of osmotic learning that comes from getting to know other artists (or writers or musicians or whatever). If you go over to the house of someone whose work you admire, and you look at their bookshelves and ask about things that jump out at you, that right there can be kind of an education. I’ve even learned a lot from just going to an art store with other cartoonists. Invariably they’ll know about some drafting tool I’d never heard of, or have some preference for some brand of ink that they’ve arrived at after years of trial and error. And on a broader scale, it’s really useful to watch how someone – especially someone who’s been at it for longer – deals with issues that arise in their art and just in life in general.

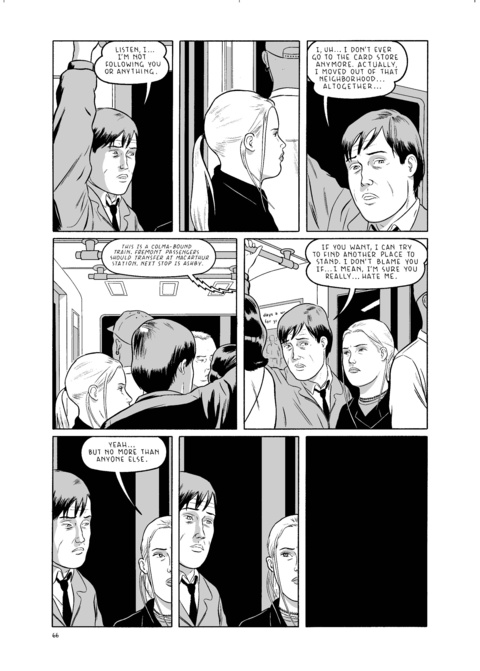

Most of your stories seem to be dealing with moments of transition, of search or shifts typical of characters in formation – for example in your aptly titled Shortcomings. What do you find so attractive in the dynamics of human failure and imperfection?

That’s a good question, but I’m afraid I don’t have a good answer! I’ve never had a premeditated plan for my work, and I certainly never set out to explore specific themes. So I guess what you’re picking up on is some sort of subconscious preoccupation of mine. I’ll put you in touch with my shrink and you can discuss.

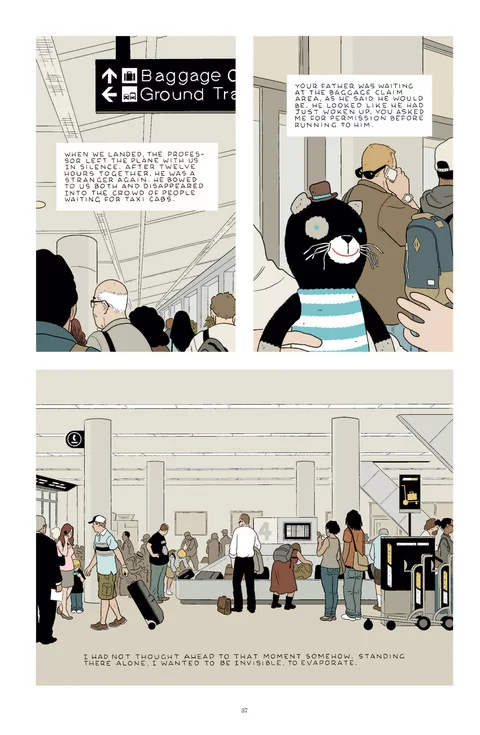

There seems to be a sense of the unresolved for your characters, all round. Where do you think your stories come from?

I’ve heard people mention – and sometimes criticize – this unresolved quality in my stories. Again, it’s nothing I set out to do. I think it’s just that I’m generally trying to write realistic stories about regular people, and in that setting it’s hard to avoid the sense that life for these characters will basically continue to get better and worse to varying degrees until they die. I know that sounds like I’m trying to be flippant or something, but the structure of my stories isn’t random. There’s a reason they end where they do, and I think the challenge for me is to do that in a way that doesn’t feel completely unsatisfying to the audience. I’m working on it.

I think my stories are also just the product of the kinds of things that I tend to gravitate towards as a reader (or movie-watcher or whatever). For example, I preferred the ending of The Sopranos to the ending of Breaking Bad. I’m probably in the minority, but that’s just my taste, and I guess on some level I’m always trying to make the kind of stories that would appeal to me.

The visual narratives in your work exist in extremely controlled environments; they are both highly personal and intimate but also interwoven with the external world. What is at the core of this human landscape you are trying to convey?

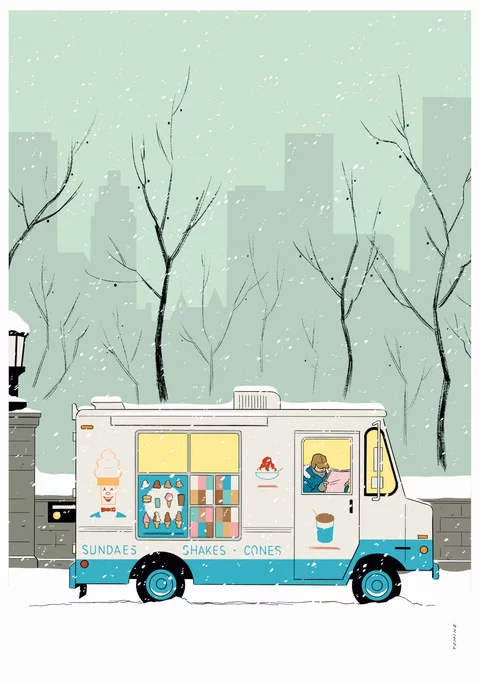

A lot of times I’m trying to capture some very small detail or nuance of behaviour, so it helps to make everything surrounding that very plain and recognizable and believable. I’m usually hoping that readers will pick up on some emotional aspect of a story rather than first struggling to decipher the images or the order in which they’re supposed to be read. Also, it’s just satisfying for me to capture a specific setting on paper. I’m drawing a scene right now that takes place in the Cheesecake Factory, and even though it’s much more laborious than just drawing a generic restaurant background, I’m taking some strange delight in drawing all the gaudy architecture and design.

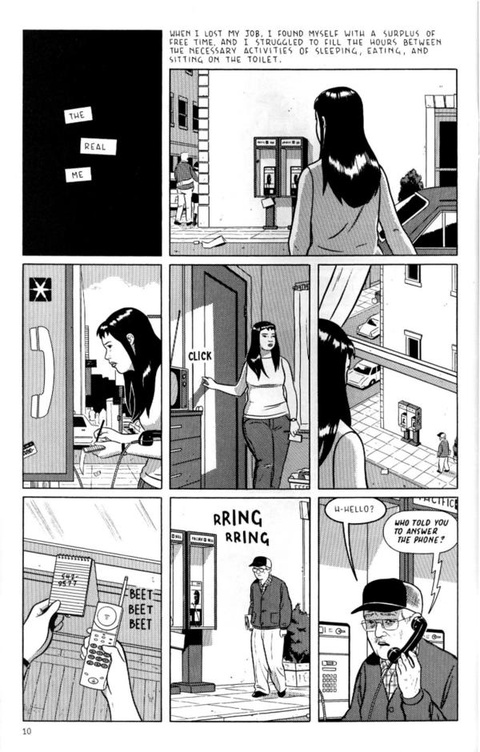

There’s a lot in your work about social anxieties and awkwardness. It often comes to a point where the characters can come across as antisocial even. I remember this Optic Nerve story, ‘Hawaiian Getaway’, where Hillary Chan, the main character, has lost her job as a telephone sales person. At one point in the story she decides to spend most of her afternoons ringing the phone booth on the other side of the street to talk to – and antagonize – random strangers as she spies on them through her bedroom window. I felt an immediate connection to Hillary; are we meant to? How do you work to make characters palpable and relatable even if they are acting in a way your readers never would?

That’s honestly the best compliment I can hear about a story. If I wrote a story that was strategically pandering to some target audience, and then someone from that audience said, ‘Hey, I really related to that story,’ that wouldn’t feel like any great accomplishment. But if I can write about fairly particular, somewhat idiosyncratic characters, and then have a range of people say they felt a connection to that character, that feels like I pulled something off. ?

Illustrations © Adrian Tomine, used with permission from Drawn & Quarterly