An unpublished Ted Hughes letter, introduced by Simon Armitage.

Ted Hughes was a prolific letter writer, perhaps from the last age of letter writing. A selection of his output, edited by Christopher Reid in 2007, runs to over six hundred pages, and my guess is that there is at least as much again which remains unpublished. Amongst other exchanges, I’m told there is an extensive and extraordinary correspondence with Seamus Heaney tucked away in the archives of Emory University, Georgia, which will hopefully see the light of day at some stage. I have about four or five letters from Ted plus a handful of cards and notes, and it’s always a thrill to see the quick and enigmatic pen strokes again, and to remember the excitement of finding an envelope on the doormat with a Devon postmark and the tell-tale handwriting.

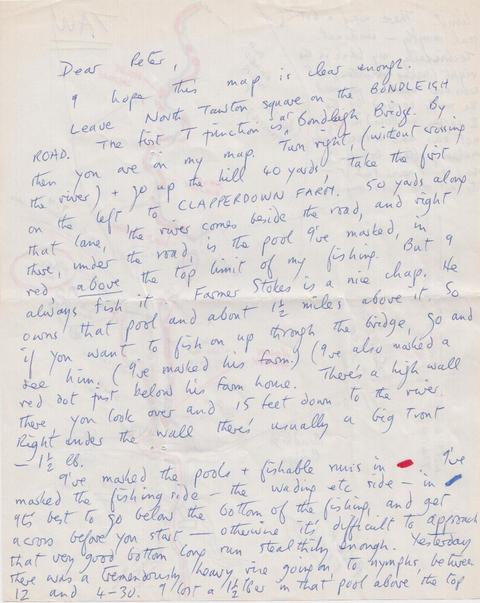

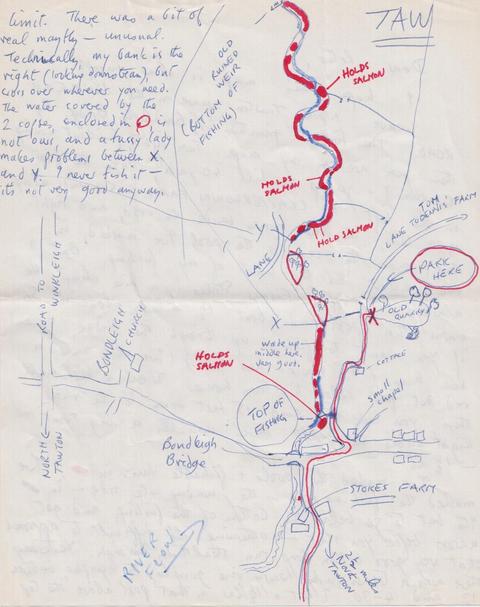

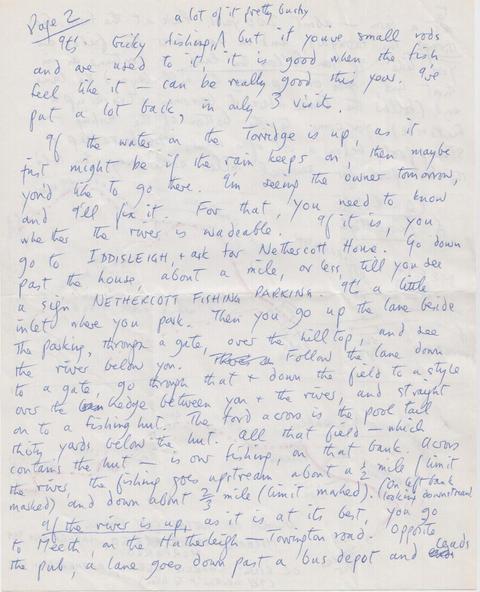

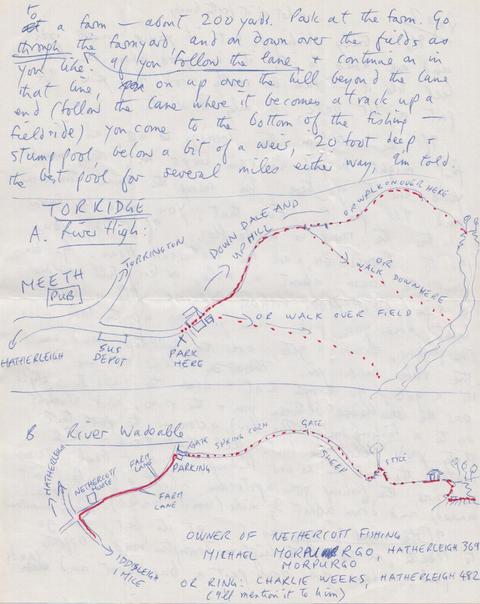

This two-page, four-sided, undated letter beginning ‘Dear Peter’ (Peter Keen, the photographer Hughes would later collaborate with in the book River) is unremarkable on the face of it, with no revelatory personal utterances, no far-reaching literary insights and no traces of the heightened poetic language which is a feature of so many of his letters. But look beyond the surface and it tells us a great deal about Hughes the poet and Hughes the man. The first issue is to do with clarity. Right from the outset Hughes hopes the accompanying map is ‘clear enough’, and just in case it isn’t provides an extended commentary and further detailed instructions. In fact there are three maps within the letter, one highlighting a section of the River Taw and two showing stretches of the Torridge (Map A for the Torridge in spate and Map B for when the river is ‘wadeable’). We learn from these that Hughes owned or shared fishing rights along both these rivers, and in Hughes’s absence Peter is being invited and initiated, as well as being told where to park, which residents to approach and who might be best avoided (‘a fussy lady makes problems between X and Y. I never fish it – it’s not very good anyway’). In my experience, it’s indicative of Hughes’s personality that he should go to such lengths to pass on the benefit of his experience and to try and ensure any recipient gets the greatest possible pleasure from it. Hughes’s philosophical concerns were complex and tangled, but he avoided the tiresome obscurity which afflicted many other poets of his generation, and the hallmark of his best poems is a purposeful clarity, brought about through pinpoint verbal accuracy and precisely observed detail. It’s the reason why the poems were admired by both critics and general readers, and why many of his adult poems made such a lasting impact when used in schools. We also get a glimpse here of Hughes the teacher. The tone of the letter reminds me a lot of his handbook Poetry in the Making, assembled from radio broadcasts aimed at young writers but in my view required reading for aspiring and accomplished poets of any age and experience. At one point in the book, he suggests that without the right techniques for accessing ideas the imagination will languish like a fish in the pond of someone who doesn’t know how to fish. In fact if the word ‘fish’ in this letter is substituted for the word ‘poem’, we have a rather interesting extended metaphor on the nature of poetic composition. Given the number of poems Hughes wrote in his life and the number of days he evidently spent fishing, there must presumably be some correlation between the two, and a picture emerges of Hughes reeling in as many poems from those Devon rivers as he did salmon or trout.

The other point which this letter illustrates is Hughes’s depth of local knowledge, though it doesn’t surprise me. During his upbringing in the Calder Valley in West Yorkshire Hughes became intimately familiar with the surrounding landscape of moors and cloughs, and the same thing appears to have happened with the fields, copses and watercourses of north Devon where he eventually made his home. For all his desire for privacy Hughes was never going to be confined within the walls of his house or the borders of his garden, though in this letter there’s an element of stealth – an awareness not just of roads and villages but of byways, backwaters, farm-tracks and paths, a means of getting out and about under the radar. A more arcane form of knowledge comes in his description of the river itself, an understanding of its rhythms and moods and the movements and behaviour of the fish populations within it. This extends as far as actually referring to one particular fish, a ‘big trout – 1½ lb’ and where to find it (over a fifteen foot wall, by Farmer Stokes’s place), as if that trout were someone he knew personally, if not by name then at least by habit.

I’m embarrassingly ignorant on the subject of fishing, so I don’t know what he means by ‘nymphs’ and ‘a bit of real mayfly’. Embarrassed because my wife’s grandfather was a well known fly-fisherman in the Tregaron area of Wales, and her father’s ashes are scattered along the banks of the River Barle near Simonsbath on Exmoor, where he spent hundreds of hours doing . . . whatever fishermen do. Embarrassed also because once, on a visit to his house, Ted took me on a short evening walk along the side of a river – possibly along one of the stretches mentioned in these letters – and talked about fishing, and I kept quiet, not knowing one end of a rod from the other, but happy just to be in his company and to listen to his voice. We stopped for a while near some sort of marker stone or commemorative plaque on the bank, then after a few quite moments he said, ‘But it’s dead now.’ He was talking about the river itself, and the devastating effects of pollution on the fish stocks. I hadn’t realized at the time how concerned Ted was with the environment, and how involved he was with campaigning across the county, writing to the government about what he saw as an impending natural disaster and even giving evidence at a hearing about a proposed water treatment plant in Bideford. This letter, with its tone of optimism and boyish enthusiasm, would have pre-dated my visit to his deceased river by perhaps twenty years, and more than anything it makes me realize how much it must have pained Hughes to witness that demise.

On a more upbeat note, it’s reassuring to see a spelling mistake (‘style’ for stile) and I love the maps. As a geography graduate, I once dreamed of joining the Ordnance Survey, but became disillusioned once I realized that it was essentially a maths-based activity involving compass bearings, theodolites and advanced trigonometry. Hughes’s maps are old-school, the kind we find in the front of ancient books, drawn with a free hand and free mind. I like the kinks in the road, the candy-floss trees, the curve of the walls across the fields, the toy building blocks of Bondleigh Church, and of course the thick red lines along the banks of the river, where the fishing will be best if the fish ‘feel like it’, like a thermal image revealing a layer of information not available to the naked eye. It speaks of someone not just in touch with the landscape around him but in tune with it, feeling it deeply, and always trying to put that physical response into words.

Dear Peter,

I hope this map is clear enough.

Leave North Tawton square on the BONDLEIGH ROAD. The first T junction is at Bondleigh Bridge. By then you are on my map. Turn right, (without crossing the river) + go up the hill 40 yards, take the first on the left, to CLAPPERDOWN FARM. 50 yards along that lane, the river comes beside the road, and right there, under the road, is the pool I’ve marked, in red, above the top limit of my fishing. But I always fish it. Farmer Stokes is a nice chap. He owns that pool and about 1½ miles above it. So if you want to fish on up through the bridge, go and see him. (I’ve marked his farm.) (I’ve also marked a red dot just below his farm house. There’s a high wall there, you look over and 15 feet down to the river. Right under the wall there’s usually a big trout – 1½ lb.

I’ve marked the pools + fishable runs in [red]. I’ve marked the fishing side – the wading etc side – in [blue]. It’s best to go below the bottom of the fishing, and get across before you start – otherwise it’s difficult to approach that very good bottom long run stealthily enough. Yesterday there was a tremendously heavy rise going on, to nymphs, between 12 and 4:30. I lost a 1 ½ lb-er in that pool above the top [end of page] limit. There was a bit of real mayfly – unusual. Technically, my bank is the right (looking downstream), but cross over wherever you need. The water covered by the 2 copses enclosed in [red circle], is not ours, and a fussy lady makes problems between X and Y. I never fish it – it’s not very good anyway.

[MAP]

It’s tricky fishing, a lot of it pretty bushy, but if you’ve small rods and are used to it, it is good when the fish feel like it – can be really good this year. I’ve put a lot back, in only 3 visits.

If the water on the Torridge is up, as it just might be if the rain keeps on, then maybe you’d like to go there. I’m seeing the owner tomorrow, and I’ll fix it. For that, you need to know whether the river is wadeable. If it is, you go to IDDISLEIGH + ask for Nethercott House. Go down past the house, about a mile, or less, till you see a sign NETHERCOTT FISHING PARKING. It’s a little inlet where you park. Then you go up the lane beside the parking, through a gate, over the hill top, and see the river below you. Follow the lane down to a gate, go through that + down the field to a style over the hedge between you + the river, and straight on to a fishing hut. The ford across is the pool tail thirty yards below the hut. All that field – which contains the hut – is our fishing, on that bank. Across the river, the fishing goes upstream about a ½ mile (limit marked) and down about 2/3 mile (limit marked). (On left bank looking downstream).

If the river is up, as it is at its best, you go to the Meeth, on the Hatherleigh – Torrington road. Opposite the pub, a lane goes down past a bus depot and leads [end of page] to a farm – about 200 yards. Park at the farm. Go through the farmyard, and on down over the fields as you like. If you follow the lane + continue on in that line, on up over the hill beyond the lane end (follow the lane where it becomes a track up a fieldside) you come to the bottom of the fishing – stump pool, below a bit of a weir, 20 foot deep + the best pool for several miles either way, I’m told.

[MAP]

The Ted Hughes letter reproduction was published here with the generous permission of the British Library and the Estate of Ted Hughes.

Photograph courtesy of the Estate of Fay Godwin and the British Library