He was bringing them drinks – a Castle for him, a Zambezi for her – when he walked into it. Things had been fine when he left with their order, but now they had morphed into animals, all bared fangs, vicious, bloodthirsty. He didn’t know their language but understood it in their boiling voices, the heat on their faces, how they singed each other with their eyes.

He hesitated by the entrance, deciding what to do. Turn on his heel and go back? Wait for the storm to pass? Proceed to the table like nothing was happening? He caught the man’s eye and gave a relieved nod, looked to him for a sign. The man continued speaking like spitting, without acknowledging him; he might as well not have been there. Hot blood roared in his head; if there was anything, a-n-y-t-h-i-n-g he hated most in the world, it was for someone to look right at him and still ignore him. And not just any someone, but a midget at that – the man was such a shrimp that even his wife could pee on him squatting.

He was standing like that, deciding what to do, when Francis, the manager, came down the hallway pushing a trolley, which left him no choice but to thrust himself quickly into the room. No need to give the man the opportunity to show he was manager, which he was always dying to do. He balanced the tray and moved with careful steps, the way you approach a rabid dog. The woman looked at him like she had never seen him before. It stung. He had done things for her. The midget too. Just that morning he had rescued the woman from a terrible downpour by stopping for her in the jeep and driving her the rest of the way to her cottage; once there, he had escorted her to the door under an umbrella. And now this treatment? This treatment, really? Mnccc.

He opened and served the sweaty bottles without smiling, without trying to meet their eyes; if they were going to be like that then, fine, he could be like that too – his middle name was not Jesus and he did not have to be nice. The thought gave him some satisfaction and he begun to hum, softly, but still loud enough for them to hear. He was encouraged now by the sudden drop in their voices; no doubt they didn’t expect him to behave as he was doing. They were probably even talking about him too, this he could tell from the shift in their voices. If someone is talking about you, you just know it, even if you don’t understand the language. It’s a feeling.

‘Tivuschutyzoberdustryongstiotchachadct,’ it sounded like the man said.

‘Vzhustubinzhuclar,’ the woman said, whatever it meant. He had, until that point, thought her an effortlessly gorgeous woman. Whenever he saw her – at mealtimes, in the library where she liked to sit and read, at the veranda upstairs, or just roaming around the lodge, her beauty never failed to surprise him, as if he were encountering it for the first time. He revelled in it, like it was meant for him alone. It was this beauty that motivated him to go out of his way with his niceness, to do things for her. Come to think of it, though, she wasn’t even that beautiful. No. Not with those perpetually startled eyes, not with that long forehead. Besides, she had no ass. And the midget – the midget was not even worth talking about.

It pleased him to find that he was not even bothered by their talking about him. They didn’t count, not any more. He took his time picking up the tray before strolling off, making it a point not to say, ‘Enjoy your drinks,’ which he was supposed to. Enjoy your drinks. Why on earth did one have to tell an adult to enjoy his drink, his food – things that went into his own stomach? Mnccc. Nonsense.

He was nearing the end of the passage when he heard a scream behind him. A few doors down, Musa, the chef, bobbed her head out of the kitchen and said, ‘What?’ with her long arms. He shook his head: I don’t know. The scream was short-lived, and all was quiet again. Musa shrugged, ducked back into the kitchen. Should he go back and check on them? But why, really, why? In life there were people who deserved to be checked on, but not these two. He sat the tray on an end table and headed back. It was not to check on them; it was in case Francis got wind of it, whatever it was – he did not want to be interrogated on where he’d been, why he hadn’t responded.

He found them huddled under the table. It had not struck him, until that moment when he saw them like that – a mess of tangled limbs, like silly kids really – how young they were. They could not have been out of their twenties. Which meant he was older than them, at least by a few years. Which counted for something. Which said they had no business treating him the way they did. Which made him want to pluck them from under the table and slap them like he would his young siblings if they needed it.

The woman pointed to the bat that was dancing in circles. He had already spotted Casper; a small frantic thing flying around the room. He was used to him coming out at the wrong moments and scaring some of the lodgers. Just yesterday, he had been called by a group of writers for the same reason. Casper had settled by the time he got there and he had not had to do anything, which was a waste of his time. The writers, all of them adults, big men included, had carried on without shame.

‘It’s a bat,’ the woman said.

‘I know,’ Mukuka said. He thrust his hands in his pockets and filled the doorway. His reflection looked back at him from the opposite window and he was pleased with what he saw. He took pride in his appearance and it showed. His white shirt was always spotless and wrinkle-free no matter the time of day, face clean-shaven, hair cropped close to his forehead, shoes polished. Even Francis, who had something to say about everything at Zambezi Lodge, never had anything bad to say about his appearance.

‘Can it be removed?’ the midget said. He was not spitting now, no. Subdued is what he was. He reminded Mukuka of a poor son-in-law negotiating an overwhelming bride price.

‘You mean the bat?’ Mukuka said. And Casper, as if he were hearing the conversation, as if he knew what was in Mukuka’s head, danced and danced.

‘Ihm,’ Mukuka looked pensive, scratched his head. ‘I have to find someone from the animal department or something. I’m not really trained to remove bats,’ he said. The man bit his lower lip. A look of frustration crossed the woman’s face. It all pleased Mukuka.

‘Or, you can leave the room and go somewhere, maybe the bar,’ he said, his voice satisfied. The woman looked at Casper, who continued round and round and round.

‘I don’t know, what if I’m walking to the door and it gets me on the neck? I heard they bite and they can have rabies. Or even worse, Ebola,’ the woman said. Mukuka took his hands out of his pockets and frowned. The midget said something sharp in his language. The woman looked very shocked, and then began to cry. It came out all at once, the rush of tears, the sobbing, and Mukuka was caught off guard by the emotion of it, the strangeness of it. He was no longer sure if she was crying because of the bat, or for something else. His instincts told him it was something else. He stepped into the room and walked toward them. By now, Casper had tucked himself behind a beam.

‘Please don’t cry, madam, the bat is gone. It’s gone, see?’ Mukuka said. His voice was something between coaxing and desperation. She covered her face with her hands and sobbed and sobbed, her upper body convulsing. Mukuka was not used to this, and he had not been told, when he was hired just a couple of months ago, what to do in such a situation. He looked at the husband to say something, do something, but the man pursed his thin lips and crawled out from under the table, grabbed his leather bag from the floor and stormed off.

‘Where are you going, you midget you?’ Mukuka said, but this was spoken quietly, inside his head. He wondered if he should go and find someone – Francis, no, not Francis. A woman. Musa or one of the girls maybe, to come and see about this. Maybe they would know what to do. He stood there thinking about it while she sobbed and sobbed. Then it occurred to him that, no, he didn’t need to involve anyone after all. Not because this was a private matter, but because he had never really been alone with her like this. Her beauty had returned now, and she looked even lovelier crying. He felt an urge to crawl under the table, hold her to his chest and wrap his strong arms around her, but he just pulled up a chair and sat there facing her, his arms folded.

‘Madam, how about a game drive before sunset, or even tomorrow?’ Mukuka’s tone was cajoling. This was a bit later, after the sobbing and heaving had stopped. He startled himself; he had not intended to say it out loud. It was just a thought; he figured maybe going out would get her out of her mood.

The problem was there weren’t that many options around Zambezi. There was the lake, and yes, it was beautiful, but being in the water made him anxious and dizzy. He also didn’t know how to swim and what if something happened to the boat and he found himself in the water? There was also the wine tasting but he didn’t think she drank, he had never seen her drink. And besides, he was terrible with pronunciation, it made him feel like an idiot having those unsayable wine names crowded in his mouth. What would have been great was a movie in town, something simple and nice and romantic but of course that was impossible; the game park was located way out of the city. Mnccc.

She looked at him as if she were hearing him from afar. Her face was peaceful and it had a kind of freshness to it, like she had in fact needed the cry.

‘Yes, sure, I think I’d like that. And thank you for staying, that was sweet of you,’ she said. He heard things in her voice – warmth, relief, tenderness. And something he couldn’t quite name but he still liked the sound of. She started to crawl out from under the table and he turned his head away, looked out the window at the pool, so she could have some dignity. The pool, like the rest of the lodge, was deserted owing to the Easter holiday. When he looked at her again she had adjusted her scarf and put on her hat and glasses and looked cheerful; you wouldn’t know, looking at her, what had just happened.

*

They went out in the safari car first thing in the morning: him sitting at the front with Moses, the driver; she in the back, sandwiched between her husband and Gloria, the guide. He had not counted on the midget coming and so was disappointed to see him emerge from the breakfast room, all dressed up in khakis to match hers, lugging a big camera. The madness from yesterday seemed to be gone from the midget’s face, and he looked happy – too happy in fact, Mukuka thought. This he had not planned for. Had he known the midget would involve himself he would not have suggested a game drive at all, he would have thought of something else. And, to add to things, it was a woman in charge of the tour. What would that make him look like, sitting in the front like a loaf of bread, not even driving? Mnccc.

Francis appeared at the door of the main reception and made a salute. They all waved to him and the car pulled off.

‘Fucking idiot. What’s he saluting us for when our pay is three weeks late? Give us our pay, motherfucker,’ Moses said between his teeth. Because Mukuka was still new to Zambezi Lodge, and therefore still learning people, he busied himself with his watch and pretended he had not heard him, even if he agreed, even if he would have liked to add that the man was not smart and didn’t deserve his managing job. But better to keep your mouth shut with these kinds of things. And besides, there was something about Moses he didn’t trust. He couldn’t put a finger on it yet but it was there.

The car stopped at the main entrance and the tall guard held out a booklet for Moses to sign. Mukuka gave the man a brief nod before they pulled off.

‘Man, I almost hit a giraffe. Just this Monday. Praise God I missed it,’ Moses said. Nervous excitement laced his voice.

‘Really,’ Mukuka said. It was not a question.

‘Oh yes-yes. There were two of them, grazing there just behind the anthill near the big baobab – that one. So I only saw the first, which I avoided fine-fine. Now the second, the second came out of nowhere. I just saw it land on my right is all I know. I mean I didn’t even see it jump, it’s like the thing just flew.’

‘Ha,’ Mukuka said.

‘Exactly. I can’t even imagine – do you know how much just one of those things costs?’ Moses said. His voice had fattened now, and it said that yes, indeed, it could not even imagine, said that each of those things cost an enormous amount of money.

‘Ihm,’ Mukuka said. He was thinking of the day before, how she had called him sweet. Not nice, no, sweet. But what kind of sweet, exactly, had she meant? The sweet of honey? Of sugar? Dates or juicy mango? S-w-e-e-t.

They took a left where the main road curved, and the car crawled along the big fence north of Zambezi. Tall grass framed either side of the vehicle, and Mukuka was glad she was not seated in the path of stray grasses and branches – there were places where the road ran narrow and sometimes people got scratched. A footpath ran along the fence, and about 300 metres down it branched off to the left toward the Sonondo settlement where Mukuka, Moses, Gloria and the other Zambezi workers lived. It was a shortcut, but Mukuka avoided it, preferring to stay on the main road even though it took him about twice as long to get to Sonondo.

What Mukuka knew was this: beyond the fence were cheetahs, lynxes, lions and hyenas, each kind of animal separated in its own enclosure. Yes, this was a game reserve and everything, but as far as Mukuka was concerned these animals were wild. W-i-l-d. One day some idiot would surely forget to lock the gate to one of the enclosures, or a poacher would cut the fence, or one of the beasts would just somehow learn how to climb out. It might seem very unlikely, but it would happen, he knew, because these things happened; it was only a matter of time. And when it did, he did not intend to be found on no footpath, taking a shortcut to Sonondo. No, that wouldn’t be him. He fished a spotless handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his forehead. It was only morning but the sun was killing already and he perspired easily.

They stopped at the second enclosure, where the two cheetahs lay in the shade. He could hardly see for the thick bush; all that was visible of the beasts was the head of one, and just a hint of the second – the rest of the animals’ bodies were submerged in the grass. But this didn’t disappoint Mukuka; he was in fact glad because it meant they didn’t have to waste much time with the dangerous animals. In the back, the three were on their feet already, pointing and admiring. He imagined what her face looked like, her green eyes, the delicate dent in her chin.

‘They are brother and sister,’ he heard Gloria say.

‘Interesting. How old are they?’ the husband said.

‘Do they have names?’ she said. Her voice was full of awe.

‘They are Simba and Dorothy. And I think he is three and she is about a year younger. Their parents came from Livingstone, Dorothy was born here. She almost died when she was a couple of months old, though – we think some tourists accidentally fed her poisonous treats,’ Gloria said.

They stood like that, watching the cheetahs they couldn’t quite see clearly. After a while the midget said, ‘Well, they’re not moving.’ It was one of those obvious observations that didn’t even need to be said.

‘Yes, they’re resting. They don’t really run around a lot because there isn’t much space in there,’ Gloria said.

‘If they’re not moving maybe we should go. See other things,’ the midget said. There was a slight twinge of impatience in his voice. It annoyed Mukuka even if he himself was ready to go. It was he who had suggested the tour, so what was the midget calling the shots for?

He imagined the cheetahs getting up from their lazing, somehow making it through the fence out of a hole that had magically appeared, grabbing the midget and carrying him back to their enclosure for an afternoon snack, the magic hole closing behind them. He knew it was an awful thought but he liked it – liked it so much that he had to suppress a satisfied laugh. Gloria slapped the roof of the car to say they should get moving. Moses started the engine and they snaked along once more.

There was no sign of the lion, the lynx or the hyena in their respective enclosures, and so the car kept on. They turned left at the end of the fence and ploughed through the grass, headed toward the thick bush. It was hot, but there was something comforting about the smell of earth and leaves, something thrilling about how the long grass raced toward the windshield as if it would crack it open, before the car’s tyres devoured it.

‘It’s a pity the other animals weren’t there, I really wanted to see the lion,’ she said. There was a hint of disappointment in her voice. Mukuka was surprised by how her sadness got to him, how it made him feel sorry for being glad, earlier, that there hadn’t been animals at the fence. It was not a wonderful feeling, and he regretted that there was nothing he could do about the situation.

‘I know. We’ll try again on our way back,’ Gloria said. ‘They’re probably just at a separate part of their enclosures. Sometimes it’s hit-and-miss with them, depends on timing, but don’t worry, there are other animals to see.’ Her voice was sympathetic, and for the first time, Mukuka was glad she was there with them, soothing her.

‘It’s sad we can’t text them to get ready for us we are coming, no?’ the midget said. He laughed at his own joke, and would have laughed by himself had not Gloria joined out of politeness. Mukuka had never heard the midget laugh before, and was amazed by the power of the sound. He turned around, perhaps to convince himself that a midget could really laugh like a big man, and yes, sure enough, Mukuka saw that it was the midget indeed, laughing the laugh. But what pleased him was the fact that she was not laughing with him; her face was turned to the side, carefully scanning the landscape.

They found the zebra waiting by the man-made lake, like the animals had heard the group and needed a ride somewhere important. She gasped from the backseat and leaned her head out of the car. Mukuka wanted to tell her to be careful, not to reach out that far. Because you never know.

‘Oh, my God, look! They’re beautiful!’ she yelled. He would not have thought to use the word ‘beautiful’ for the animals, especially it being a word that he associated with her. He looked at their poised bodies, at the sharp contrast of their black-and-white stripes, and understood what she meant. The zebra were quite pleasing to look at.

He remembered that his grandmother, MaNyathi, had told him how, once upon a time, back when animals could talk, a man had married a woman who he thought to be the most beautiful in the village, until he woke up one day in the middle of the night to see her turn into a zebra and gallop off into the woods. The astounded man stayed up to see what would happen.

Hours later, just before dawn, the animal-woman returned, changed back into a human being, and crawled into bed beside the husband she thought was sleeping. In the morning she woke up as usual and went on with the womanly business of fetching water, cleaning the home, preparing meals and tending the fields as if nothing were amiss. The stunned husband presented the matter to the village court, and it was promptly decided, after three repeated occasions of the woman turning into a zebra and bolting off into the dark, that she had to be killed. But, luckily for her, a young woman she had befriended could not bear the thought of her being slaughtered, especially as she was not harming anyone. She tipped the animal-woman off and, on the morning she was supposed to be killed, she turned into a zebra in front of the whole village and galloped away, never to be seen again.

Now the safari car skirted the edge of the herd and the zebras bolted and made off in whips of colour. She continued making noises of appreciation. The midget took pictures and Gloria narrated. Mukuka wished it had just been the two of them in the car; he would have shared the animal-woman story with her and she would have enjoyed it. He watched the fleeing animals and wondered if they were female, wondered how it was that even as they were scattering they maintained formation, speeding off in neat rows. After a while of Moses chasing the skittish herd unsuccessfully, they drove off, away from the lake.

They had just passed the big baobab when they saw the pairs of ostriches. The birds, six of them, walked right in the centre of the road like they owned it. Dani had told him once that the males had the black and white feathers and the females the grey and brown. It seemed all reversed to him, all wrong somehow – the grey-brown was unremarkable to look at, while the black and white was bold and stood out quite grandly against the bare necks. It’s the females that needed that brilliance, that needed to be attractive, Mukuka thought. When the car caught up with the ostriches, they broke into a trot. It always amazed Mukuka to see those bulky bodies, those long necks in motion, and he knew it filled her with wonder too because he heard her say, ‘Wow.’ He turned around. Their eyes met and she smiled a smile that filled the cabin. Perspiration laced his brow. He reached for the handkerchief in his pocket.

‘Could I please have some water?’ she said. She was looking at the midget, who busied himself with the camera. Mukuka quickly reached between his feet and fished a bottle from the half-open cartoon. It was warm. He cussed softly to himself; why didn’t this big-headed Moses think to use his dense head and stock cold water ahead of a tour, especially if he didn’t need to pay for it himself? And what if she rejected the warm water? What would they do, where would they find cold water in this bush? He passed it to her between the tiny window that separated the cabin and she held on a bit longer than necessary. Sweat dripped like a blob of honey down her jaw. He imagined wiping it off with a forefinger and licking it.

‘You know those things can go up to sixty kilometres per hour?’ Moses said. Mukuka wiped perspiration off his forehead. He was scolding himself for letting go of the bottle just a bit too soon. He shouldn’t have done that; what he should have done was follow her lead and keep holding on, who knows what that moment wanted to become? Her fingers had felt cool brushing against his, even if briefly. But how was it possible to feel that cool in this heat? He thought of them now, the fingers, long and slender, on his forehead. He thought of sweetness too. He slid into his thoughts like they were a cool pool, got submerged so so so deep that the fingers and sweetness became real to him, more real than the climb of the car up an incline, the heat, the blue of the sky, the red earth.

*

‘Me, I think this Julie is very nice.’ Mukuka heard the voice as if in a dream; it jolted him. He looked at the green around him and didn’t know where he was. Then he saw Moses. He glanced over his shoulder and saw them in the back. Her head was tilted up to the rain of finches overhead, dark bangs of hair on her forehead. He remembered where he was. He also remembered what he had been thinking. The memory pleased him. He smiled without meaning to.

‘But tell me, boss. Who is it, surely?’ Moses said. The car swerved to avoid a hare.

‘What?’ Mukuka said. His voice was just a little bit unsteady, like he’d been caught at something, and he was disappointed in his failure to keep it even.

‘I mean I’ve never seen your teeth before until a moment ago,’ Moses said. His voice was playful and nosy. Mukuka didn’t like the sound of it, didn’t trust it. Tree branches scratched the roof of the car. He sucked his teeth and tasted honey. They were passing the pond now, which meant they were headed back to Zambezi, and he was deeply disappointed by how soon it seemed, how the drive had felt so short. Had they really circled the whole park? What about the monkeys? The buffalo, the eland, the impala, the waterbuck? The tsessebi, the secretary bird, the porcupine, the giraffe, the warthog, the hammer cop, all these animals to see? Or had they actually seen all these things, and he’d been there but not there, lost in his thoughts. He wanted to ask Moses if they had indeed done the whole tour, but he didn’t want to embarrass himself.

‘Must be someone special,’ Moses pressed on.

‘What are you talking about, man?’ Mukuka said. His voice had recovered, but now he wanted the conversation to end. It made him uncomfortable, especially with everyone in the car.

‘Well, I’m just saying. It’s like all of a sudden you left your body and went somewhere else. So, how about you just tell it, who’s the girl?’ Moses said.

‘No, no, it’s not like that at all,’ Mukuka said, dismissively. He made to take a sly glance into the rear-view mirror, hoping to catch her. The mirror was missing; some unthinking idiot must have removed it. Mnccc.

‘Anyway, whatever has horns cannot be hidden in a sack. Check with Julia when we get to the lodge, she wanted to know when the dancers are coming. I told her you were taking a nap, seeing how gone you were.’ Moses said. He manoeuvred the car through a small swamp and muddy water splashed all over.

‘Julia?’ Mukuka said.

‘I mean the madam, at the back,’ Moses said. He tilted his head a bit to indicate back.

‘Julia, her name is Julia?’ Mukuka said. He had said it loudly, and he regretted raising his voice. He glanced over his shoulder and all three of them were turned around, looking at the distance behind them.

‘Yes, it is. I call her Julie. There’s your grandfather,’ Moses said, pointing. The car stopped. To the right of them, across the small man-made lake, was an elephant. It loomed above the grass and its trunk reached into the trees. The elephant was Mukuka’s totem animal, and seeing it always gave him a thrill, stirred a deep pride in his blood. Now he stared at it and saw nothing but a small hill.

Julie. J-u-l-i-a. He didn’t know that was her name; she hadn’t told it to him and so he just called her madam. He hated Moses for knowing a name he himself was supposed to know but didn’t, and saying it with such familiarity too, like it was his own grandmother’s name. He wondered where exactly, and how, Moses had heard the name. If he had overhead it or if she had told him herself. The way her mouth had opened, how the tongue had licked the roof of the mouth when she said the –li part. The texture of the voice.

All three of them had by now climbed down from the back and were moving toward the hill. She and the midget were talking in their language, but they were not spitting. As if knowing it was the centre of attention, the hill raised its trunk toward the sky and trumpeted. She laughed and threw her arm around the midget. He gave the camera to Gloria and they struck a pose, the hill in the background. It trumpeted and trumpeted and trumpeted until Mukuka felt sick from the sound, until he thought he’d drown it. He looked down and swallowed bitter bile, felt it sear his insides.

*

It was around nine o’clock when they got back to Zambezi. Moses turned the car around and parked in front of the reception. Doors opened behind them, and Mukuka heard her say, ‘Thank you so much, this was just so very wonderful.’ Her voice was enthused in a way that told him how her face was lit, how she was smiling. He knew she was expecting him to turn around with his usual smile and usual small talk – glad you liked it madam, yes, it was great madam, you think so madam? – but he kept his shoulders stiffened and eyes trained ahead at the group of Asians boarding the blue minibus, perhaps headed for a city tour. If she thought he was her titisi, she would find out that he wasn’t. He was Mukuka and he wasn’t at Zambezi Lodge to please her. Mncccc. Mncccccccccccc.

‘Hey hey hey boss, are you all right?’ Moses said. Mukuka nodded, surprised by the question. What did this Moses mean, are you all right? Did he not look all right? Had he just said, mnccc, out loud? Sweat covered his forehead, trickled down the sides of his face. It made his shirt, the tailored shirt that people said went well with his complexion, that accentuated his chest, that he wore specifically for her after everything that happened yesterday, stick to his back. It was not a shirt he wore often; he would have to wash it first thing when he got back to Sonondo. He yawned a yawn that was not there.

‘Ah, just tired my man. You know those writers partied late last night, I hardly slept,’ Mukuka said. Moses roared with laughter. Mukuka laughed along, but his was an uncertain, nervous laugh; he didn’t know why Moses was laughing, which meant, therefore, that he didn’t know why he himself was laughing. It felt like having earth in your mouth; it was not a good feeling.

‘True that, we’re all tired, boss,’ Moses said. It was correct that Mukuka and a small group of workers had stayed up late tending to the partying writers. It had not been until three in the morning that he had finally climbed into bed, but it was not true that he was tired from it. He had in fact enjoyed himself and had been slightly disappointed to see the party break up when it did.

‘I hear you. Tell you what, I’m off to Sonondo to pick up the cooks if you need a ride,’ Moses said.

‘Sure, great, thanks man,’ Mukuka said.

‘Fine-fine. Just wait here a minute. I want to know when I’m getting paid, I’m tired of this shit,’ Moses said. He cut the ignition and jumped out of the car. By the time the door slammed he was already jogging toward Francis’s office.

Mukuka shifted seats without getting out of the vehicle. Once he settled behind the wheel he reached for the steering and held on for a brief moment before releasing the brake and turning the ignition. The car slowly inched forward. His hands shook. At the gate the new guard waved from his shade. He waved back. He could see Moses from the side mirror now – he was running, his long arms flailing wildly. He couldn’t hear him, but he knew he was shouting and telling him to stop. He didn’t. The car picked up speed, made a right at the fence, and he was on the dusty main road. It stretched like a red belt in front of him. Tall, tall grass grew on both sides of the road, and it was green as far as he could see. He barrelled on.

He passed villas on the right, the round brick enclosure where they kept the elephant overnight, the lone petrol pump next to it. He passed the caretakers’ houses, passed the small church that he’d never set foot in, passed the children’s playing field with the lone see-saw, passed the sign that led to the dairy farm. Then he was done with houses and it was green again. His hands had long ceased shaking and he felt in charge behind the wheel. He had not known until then how much he needed the speed, needed the red dusty road racing to meet him, needed the warm wind rushing in through the windows. It felt like flying.

He thought of the first time he’d seen her. How she must have read his name from his name tag because she greeted him with his name pronounced so perfectly, like she’d said it all her life. He thought of that day when he’d saved her from the rain. Of answering her questions about the wild fruits they sometimes served for breakfast. Of giving her the emerald necklace that his sister made. Of teaching her how to say hello in his language, of waiting for her to finish crying under the table just yesterday. He thought of all these things until there was a ringing in his head, until he could see her face as clearly as if she were sitting right there by his side. Which would have been something, her sitting right there by his side while he was driving like this, flying like this. Just the two of them and nobody else. Not the midget, not Gloria, not that talkative idiot, Moses. But she was not there seated by his side, and he did not want her there anyway, sitting with him, not now that he knew the kind of person she was.

‘You think – If you think you can just play with people,’ he said to her face. He was shouting above the engine noise, and his voice filled his ears.

‘Playing with people’s heads like that, wasting people’s time,’ he said. The car’s wheels mauled the road. He clutched the steering wheel tighter, licked sweat off his upper lip.

‘When all along you know what you’re doing. Mnccc. Not even pretty to begin with, just who do you think you are?’ he said. He gassed the car harder and flew and flew. He knew now that the biggest mistake he had made was being extra nice to her. Yes, being kind. For instance, he shouldn’t have checked in on her yesterday, shouldn’t have even stayed with her all that time she was under the table, bawling like a spoilt silly child; he should have just abandoned her like she deserved, mnccc. Mncccccccccccc.

He could see the cloud of dust boiling toward him, but at first he was so deeply engrossed in her face, in what he was saying to her, that he didn’t really register what it was. He barrelled toward it. It was only when the enormous white head appeared, the horn honking wildly, that Mukuka’s stomach lurched and a sudden terror seized him. He immediately swung to the right of the narrow road and gradually applied the brakes, struggling to keep control of the belting car. He wasn’t sure he was going to make it, and this thought terrified him all over again. His mind stampeded.

Long after the two cars zipped past each other, he pulled over, cut the engine, and gingerly stepped out. The air was so hot it shocked him, the smell of dust so strong he could taste it in his mouth. The ground felt unsteady beneath his feet and he stood still, but because he still felt dizzy he had to sit down. Heat seeped through his thin trousers and seared his skin. He listened to it spread and spread until he could feel it in his bones, until his blood warmed up, until his insides began to melt, until the urge to cry seized him.

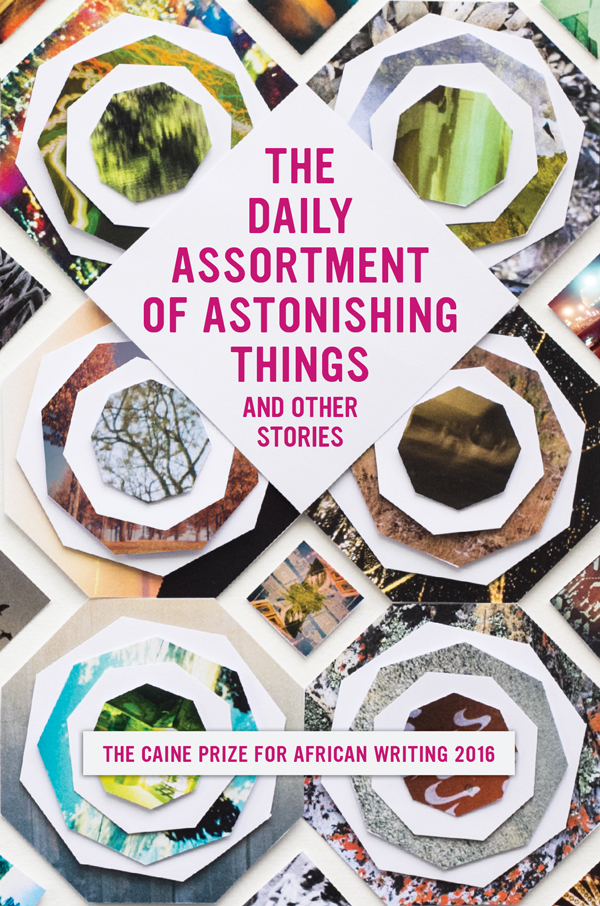

NoViolet Bulawayo’s ‘His Middle Name Was Not Jesus’ is collected in the Caine Prize for African Writing 2016 anthology, The Daily Assortment of Astonishing Things and Other Stories, published in July 2016.

Photograph © Sarah Severson