Jo Broughton’s parents were ‘too busy killing each other’, she says, to know where she went when she ran away from home aged seventeen. At school she’d performed badly, suffering from dyslexia and a stutter – but her gift for drawing offered some quiet relief from this. She was always at the risk of angering her father however, who ‘despised’ her interest in art. ‘He had that working-class attitude that you’ve got to get a job to provide safety, and get married. Be a policeman or a florist or something.’ She suspects that there was ‘a lot of fear’ in his objection to her art. She ended up carrying on in secret: ‘I always did it at the bottom of my cupboard… I’d sit there for hours, locked away, making pictures.’

She left and went to London, having secured work as an assistant in a photographer’s studio. Only on arriving at the studio did she realise what kind of photography this was. The studio produced both films and still photography for magazines, all of it pornographic.

Broughton was homeless, so she took to living at the studio as well as working there. This accidental but total immersion in the industry explains her uncommitted stance on pornography itself – as does her relationship with the studio’s director Steve Colby. He was her boss, she says, ‘but also my mentor and friend. I started making work out of his work, so how could I judge him for it?’ She has compared the atmosphere of the studio to that of a family, and acknowledges how much it helped her career.

She keeps the numerous notebooks, photographs, sketches and paintings from the studio in a cramped room in her flat in Hampstead – the only room in the flat which is off-bounds to her one-year-old son. There is also a papier-maché tea-set. On the outside, she has painted models in underwear, with fat smudges for lips, in pornographic poses. Look inside the tea-pot or a cup, and the underwear is gone, the poses even more extreme. Broughton’s time at the studio seems an indelible mark: almost all her work was either done at that time or inspired by it.

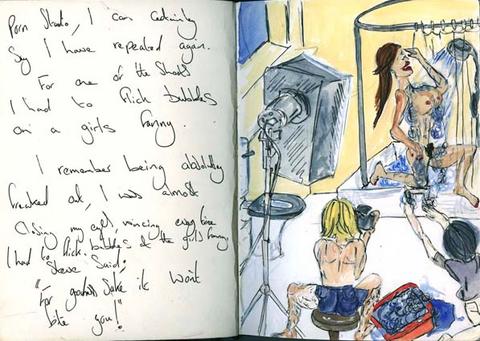

Life at the studio couldn’t have been further from the one she had fled: here was a place where freedom and permissiveness were the rule. But there was the grim side too: the ‘twisting and turning of flesh’; the sight of models, like parts in a machine, being ‘shuffled in and shuffled out’. Her main job was to make tea for the cast and crew, but she also had to clean sets – and sex toys – after use. And there were sundries, such as flicking bubbles on to a model’s vagina from just outside the frame.

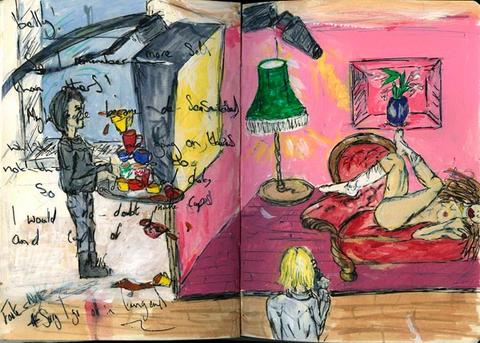

Broughton kept journals during her three years at the studio. They convey an urgent need to record the experience, to process it: there are scribbled reports of conversations, musings on the experience and vivid watercolours of the shoots. They reflect the odd mix of amusement, excitement and disgust that Broughton felt. There are reservations about Steve’s business, pity for some of its willing participants – but also a self-preserving sense of energy and fun. She laughs now remembering Keith, another assistant, who used to bring his dog to the studio in a basket; Steve’s reminiscences about the war; of eating lunch with naked models. (To avoid pressure marks on the skin, they have to be naked for at least half an hour before shooting.)

Working at the studio, Broughton saw not just the models, but who they came with. ‘Sometimes the girls would turn up with their mothers. And the mother was doing it for the over-40s and the daughter was doing it for the younger mags.’ Some girls had been introduced to the business by their boyfriends; the boyfriends would sit at the side, watching the shoot.

It was while cleaning up after hours that Broughton started to take an interest in the sets themselves: though revamped and decorated with tireless creativity, the evening always saw them empty and used, haunted by the debris of the day. In the images printed in Granta’s Sex issue, the impact is in the detail. As a setting for sex, a floor covered in balloons or enormous presents tied with bows can be amusing at first. But this is complicated by the cheerless evidence of the act itself – evidence which sits quietly in the corners of the photographs, stripping sex of its intimacy more effectively than any pornography.

Beyond the edge of one glitzy film set, we see the open door of a dark broom cupboard. An ordinary-looking hospital room is made sinister by the dildo standing tall on the bedside table. Showy underwear, belonging to no one in particular, lies twisted on the floor and left for the cleaner.

The images are eerie, amusing, grotesque and sad. Their power dawns gradually on the viewer, increasing with repeat inspections. They conjure not just loneliness, exploitation and debasement, but also a magical after-hours hush in which only the hum of a spirited, creative mind can be heard. Working in stolen moments, on her own at the end of the day, it is as though Broughton has returned to the bottom of that cupboard of her childhood home.

Artwork © Jo Broughton