Anyone who has switched on the television set, been to the cinema or entered a bookshop in the last few months will be aware that the British Raj, after three and half decades in retirement, has been making a sort of comeback. After the big-budget fantasy double-bill of Gandhi and Octopussy, we have had the blackface minstrel-show of The Far Pavilions in its TV serial incarnation, and immediately afterwards the grotesquely overpraised Jewel in the Crown. I should also include the alleged ‘documentary’ about Subhas Chandra Bose, Granada Television’s War of the Springing Tiger, which, in the finest traditions of journalistic impartiality, described India’s second-most-revered Independence leader as a ‘clown’. And lest we begin to console ourselves that the painful experiences are coming to an end, we are reminded that David Lean’s film of A Passage to India is in the offing. I remember seeing an interview with Mr Lean in The Times, in which he explained his reasons for wishing to make a film of Forster’s novel. ‘I haven’t seen Dickie Attenborough’s Gandhi yet,’ he said, ‘but as far as I’m aware, nobody has yet succeeded in putting India on the screen.’ The Indian film industry, from Satyajit Ray to Mr N. T. Rama Rao, will no doubt feel suitably humbled by the great man’s opinion.

These are dark days. Having expressed my reservations about the Gandhi film elsewhere, I have no wish to renew my quarrel with Mahatma Dickie. As for Octopussy, one can only say that its portrait of modern India was as grittily and uncompromisingly realistic as its depiction of the skill, integrity and sophistication of the British secret services.

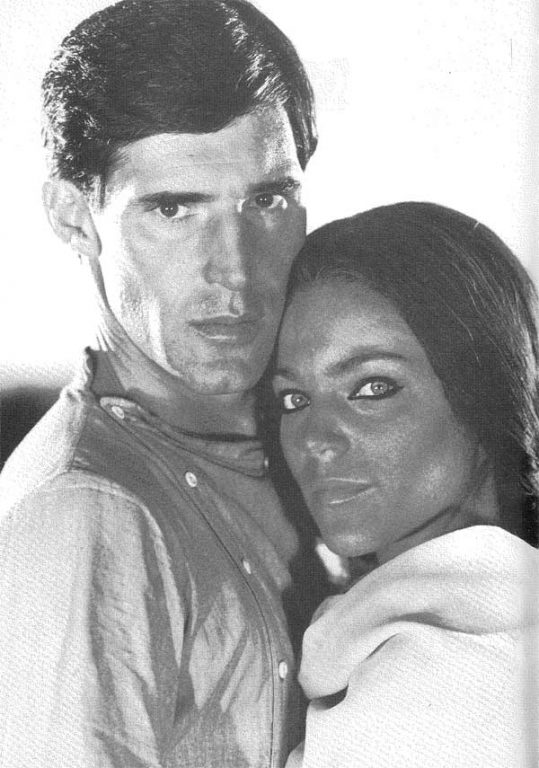

In defence of the Mahattenborough, he did allow a few Indians to be played by Indians. (One is becoming grateful for the smallest of mercies.) Those responsible for transferring The Far Pavilions to the screen would have no truck with such tomfoolery. True, Indian actors were allowed to play the villains (Saeed Jaffrey, who has turned the Raj revival into a personal cottage industry, with parts in Gandhi and The Jewel in the Crown as well, did his hissing and hand-rubbing party piece; and Sneh Gupta played the selfish princess, but unluckily for her, her entire part consisted of the interminably repeated line, ‘Ram Ram’). Meanwhile, the good-guy roles were firmly commandeered by Ben Cross, Christopher Lee, Omar Sharif, and, most memorably, Amy Irving as the good princess, whose make-up person obviously believed that Indian princesses dip their eyes in black ink and get sun-tans on their lips.

Now of course The Far Pavilions is the purest bilge. The great processing machines of TV-soap opera have taken the somewhat more fibrous garbage of the M. M. Kaye book and pureed it into easy-swallow, no-chewing-necessary drivel. Thus, the two central characters, both supposedly raised as Indians, have been lobotomized to the point of being incapable of pronouncing their own names. The man calls himself ‘A Shock’, and the woman ‘An Jooly’. Around and about them there is branding of human flesh and snakery and widow-burning by the natives. There are Pathans who cannot speak Pushto. And, to avoid offending the Christian market, we are asked to believe that the child ‘A Shock’, while being raised by Hindus and Muslims, somehow knew that neither ‘way’ was for him, and instinctively, when he wished to raise his voice in prayer, ‘prayed to the mountains’. It would be easy to conclude that such material could not possibly be taken seriously by anyone, and that it is therefore unnecessary to get worked up about it. Should we not simply rise above the twaddle, switch off our sets and not care?

I should be happier about this, the quietist option – and I shall have more to say about quietism later on – if I did not believe that it matters, it always matters, to name rubbish as rubbish; that to do otherwise is to legitimize it. I should also mind less were it not for the fact that The Far Pavilions, book as well as TV serial, is only the latest in a very long line of fake portraits inflicted by the West on the East. The creation of a false Orient of cruel-lipped princes and dusky slim-hipped maidens, of ungodliness, fire and the sword, has been brilliantly described by Edward Said in his classic study Orientalism, in which he makes clear that the purpose of such false portraits was to provide moral, cultural and artistic justification for imperialism and for its underpinning ideology, that of the racial superiority of the Caucasian over the Asiatic. Let me add only that stereotypes are easier to shrug off if yours is not the culture being stereotyped; or, at the very least, if your culture has the power to counterpunch against the stereotype. If the TV screens of the West were regularly filled by equally hyped, big-budget productions depicting the realities of India, one could stomach the odd M. M. Kaye. When praying to the mountains is the norm, the stomach begins to heave.

Paul Scott was M. M. Kaye’s agent, and it has always seemed to me a damning indictment of his literary judgement that he believed The Far Pavilions to be a good book. Even stranger is the fact that The Raj Quartet and the Kaye novel are founded on identical strategies of what, to be polite, one must call borrowing. In both cases, the central plot-motifs are lifted from earlier and much finer novels. In The Far Pavilions, the hero Ash (‘A Shock’) – raised an Indian, discovered to be a sahib, and ever afterwards torn between his two selves – will be instantly recognizable as the cardboard cut-out version of Kipling’s Kim. And the rape of Daphne Manners in the Bibighar Gardens derives just as plainly from Forster’s Passage to India. But because Kaye and Scott are vastly inferior to the writers they follow, they turn what they touch to pure lead. Where Forster’s scene in the Marabar caves retains its ambiguity and mystery, Scott gives us not one rape but a gang assault, and one perpetrated, what is more, by peasants. Smelly persons of the worst sort. So class as well as sex is violated; Daphne gets the works. It is useless, I’m sure, to suggest that if a rape must be used as the metaphor of the Indo-British connection, then surely, in the interests of accuracy, it should be the rape of an Indian woman by one or more Englishmen of whatever class…not even Forster dared to write about such a crime. So much more evocative to conjure up white society’s fear of the darkie, of big brown cocks.

You will say I am being unfair; Scott is a writer of a different calibre from M. M. Kaye. What’s more, very few of the British characters come at all well out of the Quartet – Barbie, Sarah, Daphne, none of the men. (Kaye, reviewing the TV adaptation, found it excessively rude about the British.)

In point of fact, I am not sure that Scott is so much finer an artist. Like Kaye, he has an instinct for the cliche. Sadistic, bottom-flogging policeman Merrick turns out to be (surprise!) a closet homosexual. His grammar-school origins give him (what else?) a chip on the shoulder. And all around him is a galaxy of chinless wonders, regimental grandes dames, lushes, empty-headed blondes, silly-asses, plucky young things, good sorts, bad eggs and Russian counts with eyepatches. The overall effect is rather like a literary version of Mulligatawny soup. It tries to taste Indian, but ends up being ultra-parochially British, only with too much pepper.

And yes, Scott is harsh in his portraits of many British characters; but I want to try and make a rather more difficult point, a point about form. The Quartet’s form tells us, in effect, that the history of the end of the Raj was largely composed of the doings of the officer class and its wife. Indians get walk-ons, but remain, for the most part, bit-players in their own history. Once this form has been set, it scarcely matters that individual, fictional Brits get unsympathetic treatment from their author. The form insists that they are the ones whose stories matter, and that is so much less than the whole truth that it must be called a falsehood. It will not do to argue that Scott was attempting only to portray the British in India, and that such was the nature of imperialist society that the Indians would only have had bit parts. It is no defence to say that a work adopts, in its structure, the very ethic which, in its content and tone, it pretends to dislike. It is, in fact, the case for the prosecution.

I cannot end this brief account of the Raj revival without returning to David Lean, a film director whose mere interviews merit reviews. I have already quoted his masterpiece in The Times; here now are three passages from his conversation with Derek Malcolm in the Guardian of 23 January 1984:

Forster was a bit anti-English, anti-Raj and so on. I suppose it’s a tricky thing to say, but I’m not so much. I intend to keep the balance more. I don’t believe all the English were a lot of idiots. Forster rather made them so. He came down hard against them. I’ve cut out that bit at the trial where they try to take over the court. Richard [Goodwin, the producer] wanted me to leave it in. But I said no, it just wasn’t right. They wouldn’t have done that.

As for Aziz, there’s a hell of a lot of Indian in him. They’re marvellous people but maddening sometimes, you know…. He’s a goose. But he’s warm and you like him awfully. I don’t mean that in a derogatory way – things just happen to him. He can’t help it. And Miss Quested…well, she’s a bit of a prig and a bore in the book, you know. I’ve changed her, made her more sympathetic. Forster wasn’t always very good with women.

One other thing. I’ve got rid of that ‘Not yet, not yet’ bit. You know, when the Quit India stuff comes up, and we have the passage about driving us into the sea? Forster experts have always said it was important, but the Fielding-Aziz friendship was not sustained by those sorts of things. At least I don’t think so. The book came out at the time of the trial of General Dyer and had a tremendous success in America for that reason. But I thought that bit rather tacked on. Anyway, I see it as a personal not a political story.

Forster’s lifelong refusal to permit his novel to be filmed begins to look rather sensible. But once a revisionist enterprise gets under way, the mere wishes of a dead novelist provide no obstacle. And there can be little doubt that in Britain today the refurbishment of the Empire’s tarnished image is underway. The continuing decline, the growing poverty and the meanness of spirit of much of Thatcherite Britain encourages many Britons to turn their eyes nostalgically to the lost hour of their precedence. The recrudescence of imperialist ideology and the popularity of Raj fictions put one in mind of the phantom twitchings of an amputated limb. Britain is in danger of entering a condition of cultural psychosis, in which it begins once again to strut and posture like a great power while in fact its power diminishes every year. The jewel in the crown is made, these days, of paste.

Anthony Barnett has cogently argued, in his television-essay ‘Let’s Take the “Great” out of Britain’, that the idea of a great Britain (originally just a collective term for the countries of the British Isles, but repeatedly used to bolster the myth of national grandeur) has bedevilled the actions of all post-war governments. But it was Margaret Thatcher who, in the euphoria of the Falklands victory, most plainly nailed her colours to the old colonial mast, claiming that the success in the South Atlantic proved that the British were still the people ‘who had ruled a quarter of the world.’ Shortly afterwards she called for a return to Victorian values, thus demonstrating that she had embarked upon a heroic battle against the linear passage of Time.

I am trying to say something which is not easily heard above the clamour of praise for the present spate of British-Indian fictions: that works of art, even works of entertainment, do not come into being in a social and political vacuum; and that the way they operate in a society cannot be separated from politics, from history. For every text, a context; and the rise of Raj revisionism, exemplified by the huge success of these fictions, is the artistic counterpart to the rise of conservative ideologies in modern Britain. And no matter how innocently the writers and filmmakers work, no matter how skilfully the actors act (and nobody would deny the brilliance of, for example, the performances of Susan Wooldridge as Daphne and Peggy Ashcroft as Barbie in the TV Jewel), they run the grave risk of helping to shore up that conservatism, by offering it the fictional glamour which its reality so grievously lacks.

The title of this essay derives, obviously, from that of an earlier piece (1940) by the year’s other literary phenomenon, Mr Orwell. And as I’m going to dispute its assertions about the relationship between politics and literature, I must of necessity begin by offering a summary of that essay, ‘Inside the Whale’.

It opens with a largely admiring analysis of the writing of Henry Miller:

On the face of it, no material could be less promising. When Tropic of Cancer was published the Italians were marching into Abyssinia and Hitler’s concentration camps were already bulging….It did not seem to be a moment at which a novel of outstanding value was likely to be written about American dead-beats cadging drinks in the Latin Quarter. Of course a novelist is not obliged to write directly about contemporary history, but a novelist who simply disregards the major public events of the day is generally either a footler or a plain idiot. From a mere account of the subject matter of Tropic of Cancer, most people would probably assume it to be no more than a bit of naughty-naughty left over from the twenties. Actually, nearly everyone who read it saw at once that it was…a very remarkable book. How or why remarkable?

His attempt to answer that question takes Orwell down more and more tortuous roads. He ascribes to Miller the gift of opening up a new world ‘not by revealing what is strange, but by revealing what is familiar.’ He praises him for using English ‘as a spoken language, but spoken without fear, i.e. without fear of rhetoric or of the unusual or poetic word. It is a flowing, swelling prose, a prose with rhythms in it.’ And most crucially he likens Miller to Whitman, ‘for what he is saying, after all, is “I accept”.’

Around here things begin to get a little bizarre. Orwell quite fairly points out that to say ‘I accept’ to life in the thirties ‘is to say that you accept concentration camps, rubber truncheons, Hitler, Stalin, bombs, aeroplanes, tinned food, machine guns, putsches, purges, slogans, Bedaux belts, gas masks, submarines, spies, provocateurs, press censorship, secret prisons, aspirins, Hollywood films and political murders.’ (No, I don’t know what a Bedaux belt is, either.) But in the very next paragraph he tells us that ‘precisely because, in one sense, he is passive to experience, Miller is able to get nearer to the ordinary man than is possible to more purposive writers. For the ordinary man is also passive.’ Characterizing the ordinary man as a victim, he then claims that only the Miller type of victim-books, ‘non-political…non-ethical…non-literary…non-contemporary,’ can speak with the people’s voice. So to accept concentration camps and Bedaux belts turns out to be pretty worthwhile, after all.

There follows an attack on literary fashion. Orwell, a thirty-seven-year-old patriarch, tells us that ‘when one says that a writer is fashionable one practically always means that he is admired by people under thirty.’ At first he picks easy targets – A. E. Housman’s ‘roselipt maidens’ and Rupert Brooke’s ‘Grantchester’ (‘a sort of accumulated vomit from a stomach stuffed with place-names’). But then the polemic is widened to include ‘the movement’, the politically committed generation of Auden and Spender and MacNeice. ‘On the whole,’ Orwell says, ‘the literary history of the thirties seems to justify the opinion that a writer does well to keep out of politics.’ It is true he scores some points, as when he indicates the bourgeois, boarding-school origins of just about all these literary radicals, or when he connects the popularity of Communism among British intellectuals to the general middle-class disillusion with all traditional values: ‘Patriotism, religion, the Empire, the family, the sanctity of marriage, the Old School Tie, birth, breeding, honour, discipline – anyone of ordinary education could turn the whole lot of them inside out in three minutes.’ In this vacuum of ideology, he suggests, there was still ‘the need for something to believe in,’ and Stalinist Communism ‘filled the void.’

But he distorts, too. For instance, he flays Auden for one line in the poem ‘Spain’, the one about ‘the conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder…. It could only be written,’ Orwell writes, ‘by a person to whom murder is at most a word. Personally, I would not speak so lightly of murder.’

Orwell’s accusation is that the line reveals Auden’s casualness – a politically motivated casualness – towards human life. Actually, it does nothing of the sort. The deaths referred to are those of people in war. The dying of soldiers is all too often spoken of in euphemisms: ‘sacrifice’, ‘martyrdom’, ‘fall’, and so forth. Auden has the courage to say that these killings are murders; and that if you are a combatant in a war, you accept the necessity of murders in the service of your cause. His willingness to grasp this nettle is not inhuman, but humanizing. Orwell, trying to prove the theory that political commitment distorts an artist’s vision, has lost his own habitual clear-sightedness instead.1

Returning to Henry Miller, Orwell takes up and extends Miller’s comparison of Anaïs Nin to Jonah in the whale’s belly. ‘The whale’s belly is simply a womb big enough for an adult…a storm that would sink all the battleships in the world would hardly reach you as an echo…. Miller himself is inside the whale…a willing Jonah…. He feels no impulse to alter or control the process that he is undergoing. He has performed the essential Jonah act of allowing himself to be swallowed, remaining passive, accepting. It will be seen what this amounts to. It is a species of quietism.’

And at the end of this curious essay, Orwell – who began by describing writers who ignored contemporary reality as ‘usually footlers or plain idiots’ – embraces and espouses this quietist philosophy, this cetacean version of Pangloss’s exhortation to cultiver notre jardin. ‘Progress and reaction,’ Orwell concludes, ‘have both turned out to be swindles. Seemingly there is nothing left but quietism – robbing reality of its terrors by simply submitting to it. Get inside the whale – or rather, admit you are inside the whale (for you are, of course). Give yourself over to the world-process…simply accept it, endure it, record it. That seems to be the formula that any sensitive novelist is now likely to adopt.’

The sensitive novelist’s reasons are to be found in the essay’s last sentence, in which Orwell speaks of ‘the impossibility of any major literature until the world has shaken itself into its new shape.’

And we are told that fatalism is a quality of Indian thought.

It is impossible not to include in any response to ‘Inside the Whale’ the suggestion that Orwell’s argument is much impaired by his choice, for a quietist model, of Henry Miller. In the forty-four years since the essay was first published, Miller’s reputation has more or less completely evaporated, and he now looks to be very little more than the happy pornographer beneath whose scatological surface Orwell saw such improbable depths. If we, in 1984, are asked to choose between, on the one hand, the Miller of Tropic of Cancer and ‘the first hundred pages of Black Spring’ and, on the other, the collected works of Auden, MacNeice and Spender, I doubt that many of us would go for old Henry. So it would appear that politically committed art can actually prove more durable than messages from the stomach of the fish.

It would also be wrong to go any further without discussing the senses in which Orwell uses the term ‘polities’. Six years after ‘Inside the Whale’, in the essay ‘Politics and the English Language’ (1946), he wrote: ‘In our age there is no such thing as “keeping out of politics”. All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.’

For a man as truthful, direct, intelligent, passionate and sane as Orwell, ‘politics’ had come to represent the antithesis of his own worldview. It was an underworld-become-overworld Hell on earth.

‘Politics’ was a portmanteau term which included everything he hated; no wonder he wanted to keep it out of literature.

I cannot resist the idea that Orwell’s intellect and finally his spirit, too, were broken by the horrors of the age in which he lived, the age of Hitler and Stalin (and, to be fair, by the ill health of his later years). Faced with the overwhelming evils of exterminations and purges and fire-bombings, and all the appalling manifestations of politics-gone-wild, he turned his talents to the business of constructing and also of justifying an escape route. Hence his notion of the ordinary man as victim, and therefore of passivity as the literary stance closest to that of the ordinary man. He is using this type of logic as a means of building a path back to the womb, into the whale and away from the thunder of war. This looks very like the plan of a man who has given up the struggle. Even though he knows that ‘there is no such thing as “keeping out of politics”,’ he attempts the construction of a mechanism with just that purpose. Sit it out, he recommends; we writers will be safe inside the whale, until the storm dies down. I do not presume to blame him for adopting this position. He lived in the worst of times. But it is important to dispute his conclusions, because a philosophy built on an intellectual defeat must always be rebuilt at a later point. And undoubtedly Orwell did give way to a kind of defeatism and despair. By the time he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four, sick and cloistered on Jura, he had plainly come to think that resistance was useless. Winston Smith considers himself a dead man from the moment he rebels. The secret book of the dissidents turns out to have been written by the Thought Police. All protest must end in Room 101. In an age when it often appears that we have all agreed to believe in entropy, in the proposition that things fall apart, that history is the irreversible process by which everything gradually gets worse, the unrelieved pessimism of Nineteen Eighty-Four goes some way towards explaining the book’s status as a true myth of our times.

What is more (and this connects the year’s parallel phenomena of Empire-revivalism and Orwellmania), the quietist option, the exhortation to submit to events, is an intrinsically conservative one. When intellectuals and artists withdraw from the fray, politicians feel safer. Once, the right and left in Britain used to argue about which of them ‘owned’ Orwell. In those days both sides wanted him; and, as Raymond Williams has said, the tug-of-war did his memory little honour. I have no wish to reopen these old hostilities; but the truth cannot be avoided, and the truth is that passivity always serves the interests of the status quo, of the people already at the top of the heap, and the Orwell of ‘Inside the Whale’ and Nineteen Eighty-Four is advocating ideas that can only be of service to our masters. If resistance is useless, those whom one might otherwise resist become omnipotent.

It is much easier to find common ground with Orwell when he comes to discuss the relationship between politics and language. The discoverer of Newspeak was aware that ‘when the general (political) atmosphere is bad, language must suffer.’ In ‘Politics and the English Language’ he gives us a series of telling examples of the perversion of meaning for political purposes. ‘Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet Press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution are almost always made with intent to deceive,’ he writes. He also provides beautiful parodies of politicians’ metaphor-mixing: ‘The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song, the jackboot is thrown into the melting pot.’ Recently, I came across a worthy descendant of these grand old howlers: The Times, reporting the smuggling of classified documents out of Civil Service departments, referred to the increased frequency of ‘leaks’ from ‘a high-level mole’.

It’s odd, though, that the author of Animal Farm, the creator of so much of the vocabulary through which we now comprehend these distortions – doublethink, thoughtcrime, and the rest – should have been unwilling to concede that literature was best able to defend language, to do battle with the twisters, precisely by entering the political arena. The writers of Group 47 in post-war Germany – Grass, Böll and the rest, with their ‘rubble literature’, whose purpose and great achievement was to rebuild the German language from the rubble of Nazism – are prime instances of this power. So, in quite another way, is a writer like Joseph Heller. In Good as Gold the character of the Presidential aide Ralph provides Heller with some superb satire at the expense of Washingtonspeak. Ralph speaks in sentences that usually conclude by contradicting their beginnings: ‘This Administration will back you all the way until it has to.’ ‘This President doesn’t want yes-men. What we want are independent men of integrity who will agree with all our decisions after we make them.’

Every time Ralph opens his oxymoronic mouth he reveals the limitations of Orwell’s view of the interaction between literature and politics. It is a view which excludes comedy, satire, deflation; because of course the writer need not always be the servant of some beetle-browed ideology. He can also be its critic, its antagonist, its scourge. From Swift to Solzhenitsyn, writers have discharged this role with honour. And remember Napoleon the Pig.

Just as it is untrue that politics ruins literature (even among ‘ideological’ political writers, Orwell’s case would founder on the great rock of Pablo Neruda), so it is by no means axiomatic that the ‘ordinary man’, I’homme moyen sensuel, is politically passive. We have seen that the myth of this inert commoner was a part of Orwell’s logic of retreat; but it is nevertheless worth reminding ourselves of just a few instances in which the ‘ordinary man’ – not to mention the ‘ordinary woman’ – has been anything but inactive. We may not approve of Khomeini’s Iran, but the revolution there was a genuine mass movement. So is the revolution in Nicaragua. And so, let us not forget, was the Indian revolution. I wonder if independence would have arrived in 1947 if the masses, ignoring Congress and Muslim League, had remained seated inside what would have had to be a very large whale indeed.

The truth is that there is no whale. We live in a world without hiding places; the missiles have made sure of that. However much we may wish to return to the womb, we cannot be unborn. So we are left with a fairly straightforward choice. Either we agree to delude ourselves, to lose ourselves in the fantasy of the great fish – for which a second metaphor is that of Pangloss’s garden and for which a third would be the position adopted by the ostrich in time of danger; or we can do what all human beings do instinctively when they realize that the womb has been lost for ever: we can make the very devil of a racket. Certainly, when we cry, we cry partly for the safety we have lost; but we also cry to affirm ourselves, to say, here I am, I matter, too – you’re going to have to reckon with me. So, in place of Jonah’s womb, I am recommending the ancient tradition of making as big a fuss, as noisy a complaint about the world as is humanly possible. Where Orwell wished quietism, let there be rowdyism; in place of the whale, the protesting wail. If we can cease envisaging ourselves as metaphorical foetuses, and substitute the image of a newborn child, then that will be at least a small intellectual advance. In time, perhaps, we may even learn to toddle.

I must make one thing plain. I am not saying that all literature must now be of this protesting, noisy type. Perish the thought; now that we are babies fresh from the womb, we must find it possible to laugh and wonder as well as rage and weep. I have no wish to nail myself, let alone anyone else, to the tree of political literature for the rest of my writing life. Lewis Carroll and Italo Calvino are as important to literature as Swift or Brecht. What I am saying is that politics and literature, like sport and politics, do mix, are inextricably mixed, and that that mixture has consequences.

The modern world lacks not only hiding places, but certainties. There is no consensus about reality between, for example, the nations of the North and of the South. What President Reagan says is happening in Central America differs so radically from, say, the Sandinista version that there is almost no common ground. It becomes necessary to take sides, to say whether or not one thinks of Nicaragua as the United States’ ‘front yard’. (Vietnam, you will recall, was the ‘back yard’.) It seems to me imperative that literature enter such arguments, because what is being disputed is nothing less than what is the case, what is truth and what untruth. If writers leave the business of making pictures of the world to politicians, it will be one of history’s great and most abject abdications.

Outside the whale is the unceasing storm, the continual quarrel, the dialectic of history. Outside the whale there is a genuine need for political fiction, for books that draw new and better maps of reality, and make new languages with which we can understand the world. Outside the whale we see that we are all irradiated by history, we are radioactive with history and politics; we see that it can be as false to create a politics-free fictional universe as to create one in which nobody needs to work or eat or hate or love or sleep. Outside the whale it becomes necessary, and even exhilarating, to grapple with the special problems created by the incorporation of political material, because politics is by turns farce and tragedy, and sometimes (e.g. Zia’s Pakistan) both at once. Outside the whale the writer is obliged to accept that he (or she) is part of the crowd, part of the ocean, part of the storm, so that objectivity becomes a great dream, like perfection, an unattainable goal for which one must struggle in spite of the impossibility of success. Outside the whale is the world of Samuel Beckett’s famous formula: I can’t go on, I’ll go on.

This is why (to end where I began) it really is necessary to make a fuss about Raj fiction and the zombie-like revival of the defunct Empire. The various films and TV shows and books I discussed earlier propagate a number of notions about history which must be quarrelled with, as loudly and as embarrassingly as possible.

These include: the idea that non-violence makes successful revolutions; the peculiar notion that Kasturba Gandhi could have confided the secrets of her sex-life to Margaret Bourke-White; the bizarre implication that any Indians could look or speak like Amy Irving or Christopher Lee; the view (which underlies many of these works) that the British and Indians actually understood each other jolly well, and that the end of the Empire was a sort of gentlemen’s agreement between old pals at the club; the revisionist theory – see David Lean’s interviews – that we, the British, weren’t as bad as people make out; the calumny, to which the use of rape-plots lends credence, that frail English roses were in constant sexual danger from lust-crazed wogs (just such a fear lay behind General Dyer’s Amritsar massacre); and, above all, the fantasy that the British Empire represented something ‘noble’ or ‘great’ about Britain; that it was, in spite of all its flaws and meannesses and bigotries, fundamentally glamorous.

If books and films could be made and consumed in the belly of the whale, it might be possible to consider them merely as entertainment, or even, on occasion, as art. But in our whaleless world, in this world without quiet corners, there can be no easy escapes from history, from hullabaloo, from terrible, unquiet fuss.

Photograph by Daniel Ulrich

1 I owe this observation to remarks made by Stephen Spender at a group discussion involving Angela Carter, Angus Wilson, and myself, which was part of The Royal Shakespeare Company’s two-week series ‘Thoughtcrimes’ held at the Barbican. I should note that this essay results, in part, from the ideas generated by our exchange.