The woman was going to have to sit next to him, he saw, because there was only one free seat at the bar. It might have been happy hour – the place was packed, mostly with men in dark suits and recently loosened ties, the few women among them also in business garb, and all of them bellowing to be heard above the rest. When he had come in a short time before, he had taken the next to last seat himself, on the short end of the L-shaped counter, with his back to the front window and the entrance where the woman now hovered. She was poised as if on the brink of a pool, examining and calculating the depth of it.

He cocked the free chair a little away from the bar, flashed her a half-welcoming half smile, then immediately looked away, down the length of the bar, where three young women scurried to fill and refill glasses. He sensed the newcomer’s long legs slicing towards the place he had more or less offered to her, and he felt fortunate. She was tall, with a sheet of platinum hair pulled back and pinned to the back of her head, and she wore a short, furry jacket with a cream-coloured blouse beneath, and a pair of loose-cut silver lamé trousers. She was holding a large, red leather purse which she cradled and stroked in her hands like a cat. He hadn’t really noticed her feet, but from the angles of her calves and her thighs and her derrière he knew that she must be wearing high heels, like the three barmaids, who set their feet with a practiced certainty on the slats of the raised floor behind the long counter.

The woman took a moment to settle herself. She seemed a little over-sized, though by no means overweight – just tall and rather broad-shouldered for a woman. Her head and her features were large but nicely shaped. On the far side, a massive pinstriped suit held its back to her. He scraped his own chair a little further into the corner, to make room. Like when by rare good luck the airline seats an attractive stranger next to you, he thought. He must have been on a plane recently, possibly even that same day. She shrugged out of her jacket and patted it softly into place on the chair-back behind her. Seated, she balanced the red purse uneasily on her knees.

‘Excuse me.’ She turned towards him with a bright smile, her pale eyes somehow dividing around his head and rejoining on some point behind it. Her long hand reached up from the red purse; her nails were pointed, silver.

What did she want? Behind him was a napkin dispenser, wedged in the last few inches of counter space against the dark polished wood of the last of the cabinets behind the bar. He reached around and passed her a couple of napkins, puzzled, and she tightened her smile and reached again. This time he passed her the whole dispenser and watched her tug out a block of napkins two inches thick. He watched as she arranged a long pad of them on the counter. It seemed to take her a long time to be satisfied with how they lay. At last she settled the red purse on top of the pad with the air of someone putting the last exquisite touch to a flower arrangement. The purse curled up at either end to meet the rings that connected its strap, so that it resembled a little Viking ship.

‘Is it wet?’ he asked her.

‘No.’ She smiled at him, dreamily this time. ‘Not yet.’

‘You’re thinking ahead,’ he told her.

‘Always,’ she said, and offered her hand. ‘I’m ∞≤ñ≈⌂© Bergère.’

‘That’s French for “shepherdess”,’ he said. He didn’t know how he knew that. For a moment he felt the points of her nails on the butt of his palm. He’d lost her first name in a burst of senseless coloured lights and he couldn’t tell her his own name because he didn’t know it.

‘Enchantée,’ she said.

‘Et moi aussi.’

She dropped his hand. ‘My grandfather was French,’ she said. ‘But I don’t really speak it.’

‘I understand.’ He looked at her wisely, as if he understood much more than that. It seemed to him that perhaps he spoke French, though no more words appeared to him in that language.

His shepherdess was looking intently down the long slot of the service area behind the bar. ‘Cindye!’ She blew a kiss. One of the barmaids – a cute one with a flop of dark curls bouncing over one ear – pursed her crimson lips to catch it.

‘Martini!’ Miss Bergère called. Cindye held one finger up and turned away.

The shepherdess put both hands on the prows of her purse and adjusted its angle ever so slightly. ‘They have good martinis here.’ Her tone was incantatory, nothing at all like ordinary singles chatter. ‘They’re dirty.’

‘I know,’ he said, although he didn’t. He picked up the glass in front of him, which contained melted ice cubes and the dregs of an amber fluid he didn’t seem to know the word for, though he did recall the word inebriated. He finished the drink – red and fiery in his throat – and pushed the empty glass to the inner lip of the bar.

‘One more?’ said Cindye.

‘Please.’ How did he know it was spelled with a superfluous ‘e’? He rolled in his seat. Paying for the next drink was a pretext to take out his wallet and look at the Illinois driver’s license behind the plastic window inside: the name, the numbers, nothing familiar. A postage-stamp picture of a middle-aged man with a receding hairline, gaunt face, dark hollows smudged under the eyes. He looked up for the mirror behind the bar, but his angle was wrong. The only remotely reflective surface was the polished side of the cabinet and all he could make out there was a shadow. He couldn’t remember the barmaid’s name, but she looked at him strangely when he took a twenty out of the wallet, and paid herself from a pile of bills already on the table in front of him.

A handsome blonde woman sat to his left, raising a martini glass and smiling at him pleasantly. His heart lurched when he realized he didn’t know how he had come to be in this place with her, but a glass was in his hand and there seemed to be a phrase on his tongue.

‘I don’t have much time.’

‘All of us don’t.’ She sipped her drink. They hadn’t clinked glasses.

‘A little too dirty, I don’t know.’ She leaned back in her seat and peered down the length of the bar. It was like the airplane after all – turning away from the opening pleasantries, each settling into a solitary space. A woman turning away from him triggered a dark welling of despair. A wife. A daughter. He couldn’t remember and maybe it was better that way.

He was wearing a dark jacket with a sheaf of papers folded lengthwise in the inside left pocket. When he pulled it out, a smaller scrap came fluttering with it: the stub of a boarding pass from a flight out of Chicago. He let it fall and spread the sheaf open. The first page looked like some sort of itinerary, the next the beginning of an article or lecture. ‘Kindling in the Brain: A Hypothetical Etiology for Recurring Bipolar Disorder.’ On the next line appeared the same name he had seen on the driver’s license in his wallet.

I don’t have much time, he thought. Cindye. Cindye, that was her name. With that, one might begin to rebuild a world.

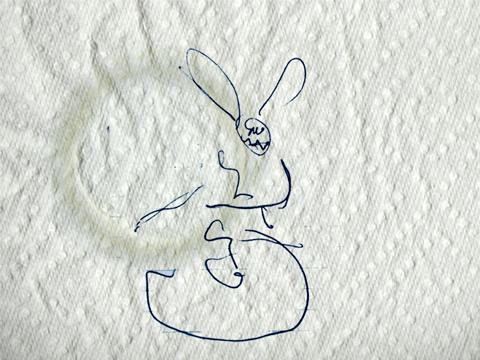

Looking at the lecture panicked him suddenly. When he put it back in his pocket he found a fountain pen clipped there, and to distract himself from the throb of terror he took the pen out and began to draw on the porous surface of another paper napkin. He seemed to have no talent for drawing, but a crude image emerged of a deranged-looking rabbit frantically pumping the pedals of a bicycle.

‘What’s that?’ The blonde woman – Bergère was her name – was leaning over his shoulder to look. He felt the warm stir of her breath on the back of his ear, with a trace of natural womanly smell which the overlay of perfume did not quite conceal.

Rabbit, Cycling. ‘It’s me,’ he told her.

She threw back her head and laughed. ‘You’re silly.’

Tittering, she put her silver nails to her lips, and he noticed for the first time that her lipstick was black. Why hadn’t he seen that before? It didn’t go with anything else she was wearing. Two surfaces in his mind slipped apart and skated away from each other. At twilight he had been on the Mall, watching the other passersby – women especially, with destinations, hurrying in their winter clothes.

He wondered if anyone had been harmed. In the failing light, he’d walked towards the long bare tooth of the Washington Monument. When he came near he found it all fenced about with concrete barriers. Maybe a plane had crashed into the spire while he watched, but no – the gabble in the bar was too casual, and the televisions were all playing sports, instead of the repeating loop of disaster. Somehow he was facing a strange, smiling woman, just taking her hand from her blackened lips. A strand of her pale hair had come loose and he reached to tuck it up behind her ear. He saw that he could kiss her then and so he did, dipping her back. Her mouth was warm and wide and slack and he felt himself sinking slowly into the lightless space inside it.

No one seemed to have noticed when they came back to the surface. The same oblivious din continued all around them. On the televisions, armoured men charged and crashed into one another. He couldn’t remember the name of the sport. The woman unzipped the red purse and took out a long, slender cigarette from a gold pack.

‘I don’t know you,’ she said. Her voice trembled slightly, like her hands.

‘I understand,’ he told her, reassuringly. Her eyes were black, with next to no iris. That was what matched the lipstick, after all. Maybe she was stoned on something, or simply drunker than she seemed, or maybe she was impaired in some way. He could have killed her, or cured her, he thought.

Cerebral event. The phrase crumbled, fell away from him in a sparkling dust. ∂↔●÷Ξỹ● . . . On the bar a red purse tilted like a little ark atop a pile of napkins, and next to that was a clumsy drawing of a frantic-looking rabbit on a bicycle. Moisture soaked up into the napkin, the dark ink ran, and the rabbit seemed to weep and bleed at the same time. He would have liked somehow to fall on the upright stake of the Washington Monument so as to impale his heart. The circles of the rabbit’s runny eyes looked up at him with an awful pathos. He clutched at his right pants pocket suddenly. There should have been a weapon in the pocket but there wasn’t.

But he had recently been on a plane. A picture of the folded knife appeared to him, nestled with other items in his toiletry kit. He must have had some sort of luggage, but he didn’t now.

He didn’t understand why the strange blonde woman next to him should look at him with such a curious expectancy. Puzzled, he lifted a pack of matches from the bar and lit the cigarette she held. When she had tasted it, he drew it out of her long fingers and took a drag himself. The pain radiating from under his left armpit and down his left arm struck him as familiar. He gave her back the cigarette, and glanced at his watch. A bolt of anxiety shot through him.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I don’t have much time.’

‘You said that.’ Her voice was remote and calm.

Now her name returned to him. ‘Have a nice evening. Miss Bergère.’

Outside in the startling cold, he looked at the front of the bar from across the street and wondered why it struck him as familiar. The crackling began again in his brain. I don’t have much time, he thought, as he looked at his watch. Maybe three minutes. Maybe five to fifteen minutes. I think that’s all I’ll ever have.

The sling-blade knife had a serrated edge and a tanto point. It was a pity to have lost it. He would have liked to drive the stake of the Washington Monument through his temples like a tent peg. Some Old Testament succubus had done that. Judith. Delilah. Jael. Jael. The woman with the silver lipstick and black nails had been named Jael. Or no. She hadn’t been.

Valiantly the red leather purse sailed across the bar. The little shepherdess! –he remembered her now. His lip felt waxy; he touched a fingertip to it and brought away a mysterious black smudge. He might have killed her, he thought. Or cured her.

There was a dusting of snow on the sidewalks. He had traveled some distance, thinking these things, and now he stood on a concrete bridge which traversed a shallow ravine, with a weakly trickling stream at the bottom. It was too late for the lecture now. He pulled it out of his pocket and tossed it over the edge.

On either side of the bridge the city continued with its noise and light, but here where he stood seemed wild and desolate. There had been another ravine, much deeper, a chasm with a cascade roaring through it, and there the bridge had been hooped with wire mesh, after too many people had hurled themselves down. Elsewhere in time there was a dry arroyo, with a handful of pilgrims climbing it slowly, resolutely, their distant figures shimmering in the heat. A line could be drawn from one gulch to the other, but it would have cost him terrible pain to restore it.

Still the pilgrims kept approaching, carrying bottomless wells of memory in the clay jars balanced on their heads. But they were still a long way off; he thought that they would never reach him.

Below a girl lay broken on the rocks, a clump of red hair frayed across her cheek. Or no. That was the redheaded Scots barmaid, elsewhere in time, in some other bar. He remembered the name of the girl in the bar. Elaine. Sweet Elaine. The song was just on the tip of his mind. But that wasn’t quite right. ۩●©Л≈ ↔●●∞⌂∂. The music faded, and with it the word; it melted like a snowflake and was gone.

Featured photograph by Paul Sableman; in-text image by Madison Smartt Bell