An unlikely series of events had put me in a remote part of Indonesia on a night dive for which I was ill-prepared and on which I had been abandoned by a more experienced dive buddy. Fortunately, the moment of primal horror passed in seconds, and the next day I carried on as if nothing had happened. I was there to learn from scientists who were observing remarkable creatures in the wild (among them, Leopard sharks and Upside Down jellyfish) before attending an international conference on the state of the oceans. And that conference, which took place the following week, confronted us all with a prospect that is truly horrific: it is likely that tropical coral reefs, which are among the most diverse, productive and beautiful ecosystems on Earth, face an extinction unparalleled in many tens of millions of years as a consequence of global warming and ocean acidification caused by humans.

I have made it my business to try to understand – and, in as far as I can, contribute to averting – this potential catastrophe and a few years ago came to the unoriginal conclusion that at the heart of the problem is a calamitous failure of imagination in our culture and politics. We live in an age of wonders, with almost daily revelations about the natural world, amazing scientific advances and even a few hopeful occurrences in human affairs. But other trends – notably the failure over the last few decades substantially to address our dependence on fossil fuels or to develop better institutions to anticipate and resolve crises – suggest that even in the best case we are in for a bumpy ride. The global climate system, says Earth scientist Wally Broecker, is an angry beast, and we are poking it with a stick.

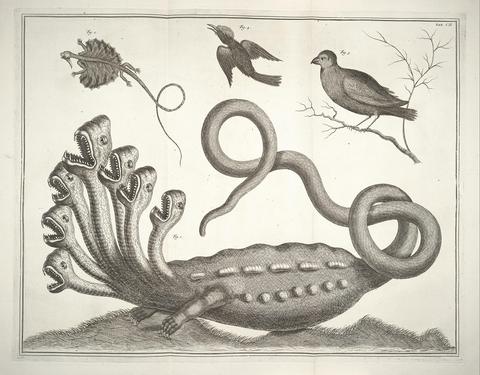

In the middle ages people believed that every creature in the natural world embodied a religious or moral lesson. Striking testament to this are the bestiaries: books of beasts which approached an art-form as illustrated manuscripts in the decades before the Black Death. In bestiaries, every animal is allegory and symbol. Since at least Hume and Darwin we no longer believe any such thing, but as we increasingly shape the world through science and technology (not to mention our sheer numbers), the animals that do thrive and evolve increasingly become corollaries of our values and concerns. The Enlightenment and the scientific method may, therefore, result in the creation of a world that really will be allegorical because we will have remade it in the shadow of our values and priorities. Perhaps the philosopher John Gray is right when he says that the only genuine historical law is a law of irony.

Science shows that every animal, even those with which we imagine ourselves to be familiar, are, when looked at closely, much more astonishing than most of us have ever imagined, and easily surpass mythical animals in beauty and bizarreness. This is as true for the Moray eel as any other. And after my encounter on the reef I determined to overcome what I knew was an irrational fear once and for all by finding out what it is actually like. I learned that there are over 200 distinct species of Moray eel. They are, I now appreciate, spectacularly beautiful. But natural selection has given them an anatomical feature that, though harmless to humans, vividly recalls the wildest edge of science fiction or horror movies.

Until very recently the conspicuous success of Morays was something of a mystery. Most carnivorous fish engulf prey into their mouths by opening them quickly from a closed position and thereby creating a sucking effect. But Morays’ mouths are already open most of the time. Further, their visible jaws are actually quite small and weak given the animal’s size. How then, do they sustain themselves? The answer, observed in 2006 for what was believed to be the first time, is astonishing. Moray eels have a second set of jaws deep at the back of their throat which shoot forward at high speed, grab the prey, and rapidly protract backwards again, pulling the prey down into the oesophagus as the animal closes its mouth. This extraordinary ability to ‘vomit’ up a second set of fearsome teeth gives the Moray the best of both worlds: it can reach out to grab its prey without moving far from its narrow hiding place.

Monsters of one kind or another are woven into virtually all the cultures of which we have record – from the earliest days of our kind, when the sabre-toothed cat Dinofelis dined regularly on our Homo habilis ancestors. But as humans expanded across the globe and, over the course of a few thousand years, exterminated or marginalized every beast that challenged our dominance, those monsters have become increasingly elusive and hard to pin down. Now, we sit astride the world and almost all the monsters are within us – the realities, challenges and consequences that we fail to face out of fear. Perhaps, as science reveals ever more wonders and possibilities, we may find the strength to face them. Understanding more about the natural world need not lead to disenchantment but it can eliminate the kinds of magical thinking with which we often harm ourselves and other beings.

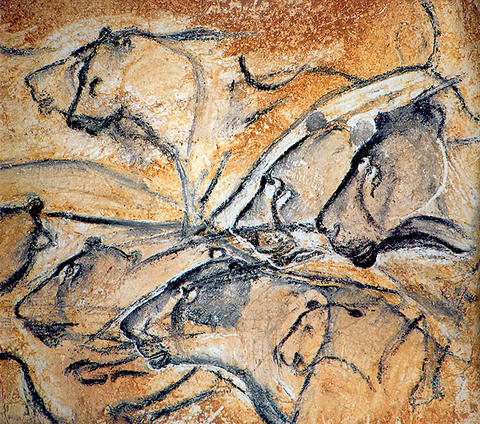

In Monster of God: The Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind, David Quammen reflects on the paintings of animals in Chauvet cave in southern France which, at around 30,000 years, are the oldest known. Writing, perhaps, with a little more wisdom than Werner Herzog brought to his remarkable film about the cave, Quammen focuses on an image of several lions gathered for attack, noting that whoever painted it did not do so with fear and loathing but with ‘a skilled hand, a calm heart, and an attentive, reverential eye.’ By the time, more than a thousand generations ago, that these paintings were created, humans had already learned to recognize the sublime in what they had previously only feared, and in this fact there may be hope.

Featured artwork by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels (detail), 1562