As a youngster and aspiring artist in the early 1970s, I learnt a lot from attending art exhibitions and visiting private studios and galleries in Lagos. It was a ritual for me to flip through newspapers eagerly to check out the cartoon page where the artists reign supreme with their take on socio-political issues in the country. My other pastime was to check out the street sign-writers and their organic form of art. The minibuses in Lagos always had philosophical slogans written on them.

In Nigeria, everyday life is noted not so much for the abundance of technology as for the fact that so much of it does not function. The country’s political rulers are not satisfying the needs of the people and are interested primarily in enriching themselves. A new enemy has also arisen in Nigeria – insecurity has intensified due to kidnapping and terrorist extremism. Yet despite the despair, the underlying attitude has remained irrepressibly optimistic. In the last three decades or more, a couple of artists have started using the tools at their disposal to analyse political developments. Fela Anikulapo-Kuti was one major artist; with his Afrobeat music, he challenged the forces of repression and corruption in governance in the state of Nigeria. He suffered great consequences but never gave up the fight till his death.

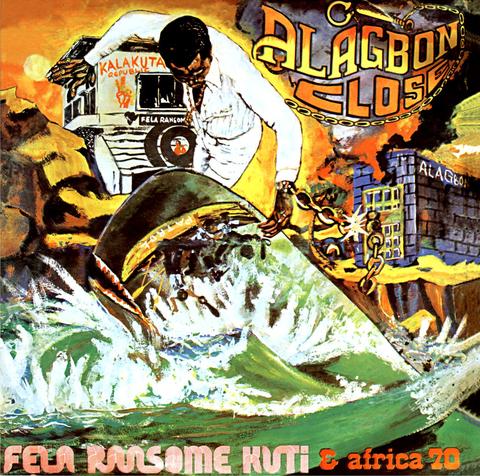

In 1974, I earned Fela’s trust and friendship through my acquaintanceship with the journalist Babatunde Harrison. Fela had just experienced his first beating and incarceration by the police and this gruesome experience inspired the hit song ‘Alagbon Close’, which was the first cover I designed. Having listened ardently to recountings of the harrowing experience from the man himself and having been privy to the stages of the composition of the tune, the cover was a fait accompli. It actually started with a drawing of Fela I had in my portfolio prior to my chance meeting with ‘Tunde Harrison, which showed the musician dancing on a mishmash of mud and rubbish. The final design of ‘Alagbon Close’s’ cover showed Fela’s ‘Kalakuta Republic’ in the background standing solidly on the left and Alagbon Close jailhouse on the right, a broken chain leading from the walls of the jail, half of which is still attached to Fela’s left wrist as he dances triumphantly over a capsizing police patrol boat and is helped, in effect, by a prodigious whale.

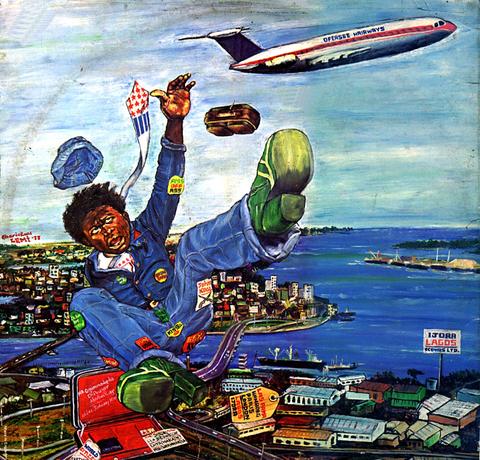

The next two album covers for No Bread and Kalakuta Show followed the tow of Fela’s vitriolic statements on vinyl. No Bread was an elaborate oil painting; portraying a mélange of social ills plaguing a developing nation; the cover forespoke of the doom to come. This cover took the best of two weeks and a trip to ‘cloud nine’ to achieve. Fela had insisted I try out a concoction of igbo (marijuana) to ‘elevate’ my talent. Not wanting to let my great friend down, I tried the herb and the resultant effect was superb, but being a teetotaller and someone with a mind of his own, I learned to be myself and thereafter tune into the right frequency. Kalakuta Show is another oil painting, this time illustrating the arrogant sacking of the ‘Republic’ in another Fela-versus-Police drama, featuring a portrait of Fela with the smoking Kalakuta Republic in the background, while Fela, his aides and his radical lawyer are hotly pursued by a baton-wielding policeman!

My association and friendship with the maverick was very cordial. I was treated like a son, friend, adviser and comrade by the Afrobeat legend. I was a travelling companion, sharing the great ideology of Pan-Africanism on some of the trips across the West African coast. Between 1974 and 1993 I designed twenty-six album covers for his music career.

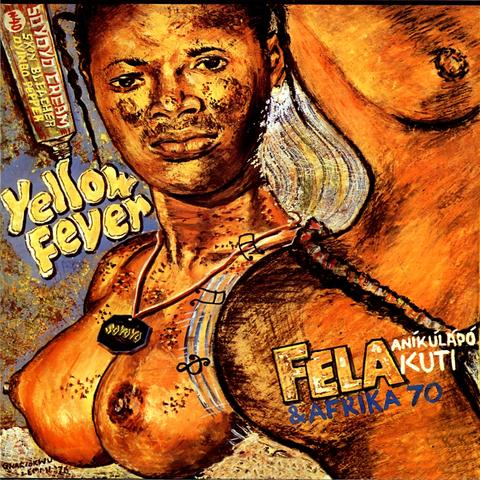

I designed the Yellow Fever cover in 1976. The song is an admonition to African women who are fond of using bleaching creams to lighten their dark skin tone, and I did use a model to express visually what Fela has orally illustrated in the song. Points of emphasis include the bad effect the bleach has on the face and bum. My life model was a girl named Kokor who was a member of the household at Kalakuta Republic. I decided it was going to be a straight-in-your-face image of misinformed African beauty. Fela had already expressed disgust at the belief that skin lightening enhances African beauty. I showcased a typical ‘offending’ cream in the top-left corner of my cover art. ‘Soyoyo Cream Skin Bleacher’ was actually my own creation. The word soyoyo is a Yoruba expression for ‘bright and glow’! I painted in the price tag of 40 naira which was high end for a cream, and yet so harmful to beauty and the psyche of African women. Fela reacted very positively when I submitted this cover for his approval and in his characteristic manner said glowingly ‘Goddamn!’, wittily adding ‘Lemi is a mutherfucker me-e-n!’ just to round up.

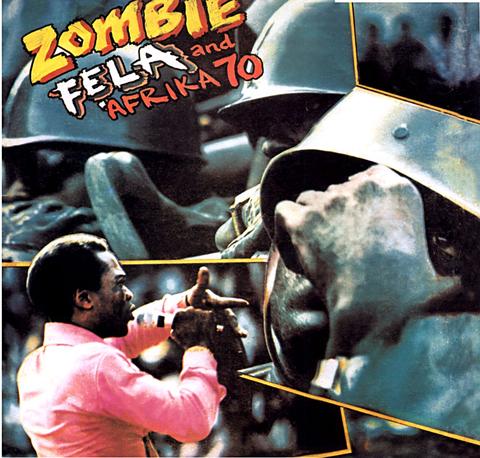

In 1976, the then-military government in Nigeria had instructed soldiers to horsewhip erring drivers on the highway. The soldiers carried out this order without impunity and with a fervour reminiscent of zombies. That was why, having been severally harassed by military personnel, Fela came up with the idea to compose ‘Zombie’. Everyone, including some military personnel from the nearby Albati Barracks, fell in love with the catchy rhythm and martial tempo, which galvanized the dancers, who wouldn’t let the song end. Fela’s saucy reprise of the Army Bugle call and horn riff got them jumping and whooping with the release of being able to mock oppressors they both feared and despised. The song became an anthem of protest for people, which was chanted under their breath anytime they felt oppressed by military personnel.

When the time came to do to create the cover art for this landmark song, I found myself unable to focus on the right idea initially. The breakthrough came right on time one Kalakuta morning just as Fela was asking how the sleeve was coming along. Tunde Kuboye, the photographer, film-maker, jazz musician husband of Fela’s niece, Frances, walked in with a bunch of his photographs taken at that year’s Independence Day military parade at Tafawa Balewa Square in central Lagos. With Tunde’s permission, I selected ten military images, and a few of Fela. I was set on making a graphic collage. Back in my studio I laid a cardboard mat on my drawing board and edited Tunde’s ten shots down to four. I was feeling like a shaman, and as I put them down, the pictures just dropped into a position reminiscent of an Ifa divination . . . subconsciously! Not wanting to take any chances, I fixed the pictures down with masking tape, then traced their position in pencil. I overlapped the photos and cut and pasted them down. Then, using a hard paintbrush and thick poster colour paint, I wrote, in freehand, the album title, Fela’s name and his band directly over the picture, outlining the result with a Rotring pen. Finally, I added the shadows.

The sleeve was an instant hit at Kalakuta, in Nigeria, Africa and around the world. It led new listeners to wonder what lay on the vinyl inside. For the initiated, it told the story of life under an oppressive military dictatorship – and what it takes to come through it feeling that you’re still somehow in command of your destiny.

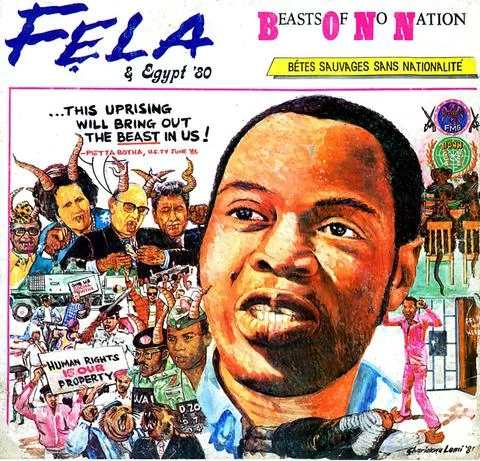

Beasts Of No Nation (B.O.N.N.) was Fela’s attack on his jailers for an eighteen-month undeserved incarceration from a trumped-up currency trafficking charge. Smarting from his experience in jail, Fela throws his punches like an enraged prize-fighter. In typical Fela style, Beasts Of No Nation made the acronym BONN, which is a disguised reference to the once de facto capital city of West Germany and the days of Adolf Hitler’s Nazism.

The music is as powerful as it gets and beneath his knife-edge, cutting sarcasm, Fela’s voice rages. It would take a serious sleeve to convey that acid tone. I knew I had to depict the evils of South African apartheid, and the failures and hypocrisy of the United Nations. I made the delegates look like rats, and I portrayed the oppressors with animal’s horns and fangs; the slavering vampires of Margaret Thatcher, South Africa’s Prime Minister, P.W. Botha, Ronald Reagan and President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire cram the frame. The quote used on the top left of the cover art is from a speech by Botha, and among my beasts are Generals Mohammed Buhari and Babatunde Idiagbon, the men responsible for Fela’s 1984 jail stint. The images of Beasts of No Nation seethe with primal urges – greed, control, vengeance – and the spirit of defiance is embodied in the demonstrators waving a placard with a line from the song, ‘Human Rights Is Our Property’. The demonstrators wear Black Power sunglasses and their pink tracksuits pulsate with pastel against the sombre palette of their enemies. Fela’s costume is the same exuberant pink, and their gestures are echoed in his triumphant Black Power salute, as he faces them across the frame, while the offending judge cowers at his feet.

Fela decided to make an incursion into the various untouchable aspects of our society. He took advantage of the sweet and seductive power of those things that are looked upon as taboo and he invited Nigeria to the debate, and I stand with resoluteness behind him to this day.

All images courtesy of Lemi Ghariokwu